China's Climate Pledge

Air Date: Week of October 10, 2025

China leads the world in wind energy, with this source accounting for 7.5% of its total energy production. At the 2025 UN Climate Summit, President Xi declared that China aims to boost its installed wind and solar capacity to 3.6 billion kilowatts, a more than six-fold increase over 2020 levels. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

China has for the first time committed to an absolute target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, by 7 to 10 percent by 2035, though it is likely to achieve greater reductions. Climate activist Jennifer Morgan previously led Greenpeace International and worked with the German government as a Special Climate Envoy. She joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss China’s growing dominance in the global clean energy transition while the current US administration doubles down on fossil fuels.

Transcript

BELTRAM: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

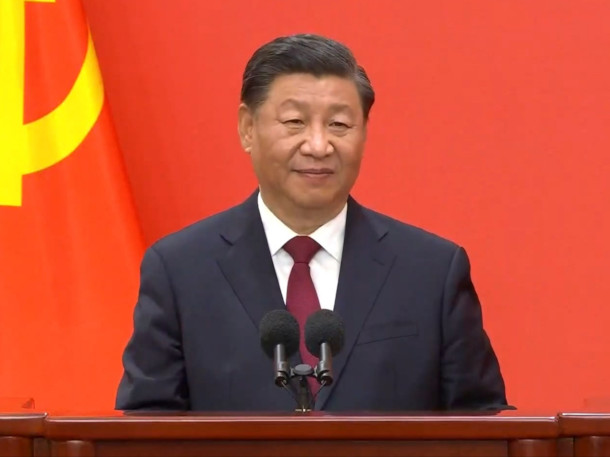

The world order is changing, just like the climate. Back in 1995 in Berlin at the first COP or Conference of the Parties of the UN climate treaty the richest nations including the US, Europe and Japan agreed to go first in reducing global warming emissions. Those rich countries were and still are most responsible for the total of human emitted CO2, and they agreed developing countries like China, India, South Africa and Brazil could keep increasing emissions while they built their economies. And until recently China, which emits the most greenhouse gases today, declined to make firm commitments to cut them. But that has all changed. While US President Donald Trump went to the recent opening of the UN General Assembly to denounce climate disruption as a hoax, China’s President Xi Jinping beamed in to commit his nation to absolute reductions.

[XI JINPING]

CURWOOD: Roughly translating, President Xi said , “Green and low carbon transition is the trend of our time. While some countries are acting against it, the international community should stay focused on the right direction.” President Xi committed to cut at least 7 to 10 percent of emissions by 2035, sequester more carbon in forests and expand electric vehicles. Long time climate activist Jennifer Morgan was in Berlin 30 years ago, has led Greenpeace International, and is a former State Secretary and Special Climate Envoy for Germany. She’s now a senior fellow at Tufts University. Jennifer Morgan, how did you feel about China finally signing on the dotted line?

MORGAN: I had mixed feelings. On the one hand, the fact that President Xi Jinping showed up in a prominent role and announced this at the Climate Summit, I thought was very good, and the fact that you can just see them moving forward. It's definitely a mindset shift for them to be moving to an absolute target with all greenhouse gasses, so that's quite good. But I really think that they missed a chance, he missed a chance, for real leadership, because the number, seven to ten percent, is much below what experts had been saying was needed to keep the 1.5 degree goal within sight, and also what's actually possible, or what's likely to even happen in China. And I had just hoped that he would be more ready to step into the vacuum and really demonstrate significant leadership at this moment.

At the UN Climate Summit, President Xi announced China's initial emission reduction target: a 7-10% decrease from peak levels. This announcement has been met with varied reactions, with some critics arguing it falls short, while others commend the establishment of a specific objective. (Photo: China News Service, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

CURWOOD: What about the Chinese culture, political culture, that any goal you set, you better make it or, you know, it can literally be your head. So they tend to understate, and they have these five year plans. I mean, politically, what kind of box do you think President Xi was in when he was making this announcement?

MORGAN: Well, from the Chinese perspective, I think they've had a time period of reduced economic growth. He has provincial leaders, who are not keen for perhaps some of these measures, because they're able to pump up their provincial economy through more coal and heavy industry. And so I think that there were those factors at play. Certainly, I think they prefer to overachieve. They've always done that, they've done this now. I mean, they were supposed to have 1200 gigawatts of wind and solar by 2030, they met that six years early. They're now at 1680 gigawatts. But I think it was a signal from a Chinese perspective, we are still here, we take this seriously. And not only that, we see it as a core part of our economic growth, but we're not willing to take too many risks.

CURWOOD: So why has it taken so long for China to fully commit? I mean, this is the 30th year of the climate treaty and technically, it's first time they've put absolute targets on the table. Why have they never done this before?

MORGAN: I think China, like other emerging economies or developing countries, you know, one factor is the lack of certainty of what is happening in their economy. They often don't know what the growth rates are going to be. They're starting from a very different point of where developed countries have started. And so there's the uncertainty of that, and not being able to be clear about what emissions are going to happen or not. But also, I think until recently, there was a sense of a choice between economic growth and climate action. And that, I think, until renewables, to build power right now is cheaper with solar and wind than with any fossil fuel, I think there was a sense there was a trade-off there. And I think they also wanted to play it from their domestic, their national perspective. China doesn't want to feel like it's being told by an international community to do something. So it really is very nationally driven, and it's not a country like others, perhaps Europe, or a country like Brazil, where there's more of a play between international expectations putting positive pressure on a country and then the country rising to that. With a country like China, you could also say the United States, it's very much domestic factors and domestic priorities that have driven that.

Since 2006, China has been the world's largest annual emitter of CO2, primarily due to its vast industrial sector and heavy reliance on coal. However, historically, the United States holds the top position for cumulative CO2 emissions since the industrial era, having emitted approximately twice the amount of CO2 as China to date. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, China's announcement came after President Trump told the UN General Assembly that climate change is, quote, the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world, and the UN General Assembly has sometimes this one day Climate Summit, and US wasn't even in attendance in that. How do you think President Trump's remarks were perceived by other nations at the summit?

MORGAN: I sensed in watching the summit that there was a sense of in some ways, togetherness, a bit of disbelief and a bit of anger, because small island nations whose very existence is threatened from climate change, many of them were there, and so they reaffirmed that. The President of Chile as well saying, this is not a time to be talking about the science. And I thought it was really striking how many leaders came and how many new nationally determined contributions were announced. So for me, it was almost as if, yes, he said this, some of them ignored it. Most of them didn't even recognize it. They just keep going because they know, they understand the science, they are experiencing these extremely devastating and expensive impacts. And you know, there was a recent Africa Climate Summit. They want to be part of the solution. Many of them are seeing new economic opportunities from the transformation to renewables, from the circular economy, from green hydrogen and steel and all of these things. There's a $2 trillion market out there right now, and the sense that I get is it didn't seem to deter or really have any major impact, except perhaps to get leaders to double down and to say, okay, this is where we need to go right now.

CURWOOD: So there was a summit in early September with India and Russia that President Xi announced his vision for a new global order that prioritizes the Global South. To what extent do you think the Global South's role is changing now regarding climate action and policy? What might that mean for the Global North?

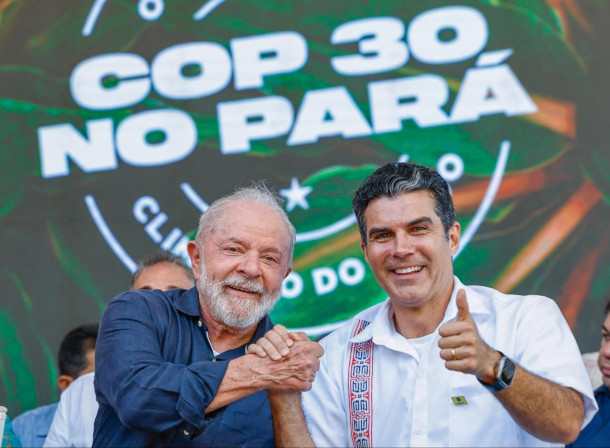

China's announcement comes ahead of COP30, the 30th UN climate conference, which will take place in Belém, Brazil, in November 2025. The key discussions will focus on limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C, implementing new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and reviewing financial commitments from COP29. This conference marks ten years since the Paris Agreement and occurs five years before a major climate target deadline, with new NDCs due this year (2025). Shown here is Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (left) and Governor of Pará Helder Barbalho (right) at a pre-COP30 celebration. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

MORGAN: I think this is a great, great and very important question, Steve, because it is changing fundamentally. And I think that developed countries need to realize this. First of all, they have to realize that and understand that China has invested over a long period of time, and they are now making very high quality, affordable, clean EVs, you know, solar, et cetera. So one question is, how does one work with China, although it's very challenging in order to accelerate that pathway to a zero carbon economy. But the other thing, I think, is what I see is much more confidence from countries like like India, like South Africa, like Brazil, of wanting to work together, not necessarily with a country from the Global North, but what kind of trade, investment, decarbonization, agreements can we make amongst ourselves. And also how, and I think going into a COP with Brazil as the host, how they can step in with their realities to set new forms of partnership. I think what it means for developed countries is that developed countries need to get much more specific. They need to be ready to do partnerships that are not extractive, in other words, don't just pull resources out of countries and use them for themselves, but actually create local value in those countries. They need to get quickly in building those types of new partnerships, a new paradigm, I would say, of cooperation.

CURWOOD: And Jennifer, before you go, the world seems to be headed past the 1.5 degrees centigrade average rise that was hoped for back at the time of the Paris Agreement in 2015. What's the reality of how things are adding up? And you might put that in the context of the upcoming climate treaty COP30 in November in Brazil.

Jennifer Morgan is an American-German environmental activist specializing in climate change policy. From 2022 to 2025, she was the special representative for international climate policy of the Federal Foreign Office in Germany. From 2016 to 2022, Morgan co-led Greenpeace International. (Photo: Photothek, Courtesy of Jennifer Morgan)

MORGAN: Well, I think the one thing for folks to remember, two things. One is in the Paris Agreement, and this has recently been reconfirmed by the International Court of Justice, that 1.5 goal is a legally binding target. And the second is that it has been overreached for a year, and it's very difficult to see how in the short term one can bring it back down. What's important is every single tenth of a degree. So we can't just see it as either or, you know, it's not like, oh, 1.5 is very difficult or won't be achievable in the short term anymore and therefore we give up. And I think that's what many actors who want to keep business as usual are trying to get this kind of sense of despair that's there. So that's kind of a bit of context. And going into COP30 this year, which Brazil is hosting in the Amazon in Belem, it's a different kind of COP this year, Steve, because in a way, you know, Paris is done the rules are all now finished, and there's been good guidance given on transitioning away from fossil fuels. But what really is lacking is the level of implementation that's required. So the world's not on track to triple renewable energy. It needs to do more to get deforestation down to zero by 2030. So it's really a COP where it will require a lot of determination to get that through, but that's what we're looking at this year.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is a Senior Fellow at the Climate Policy Lab at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, and recently stepped back from the German government as a diplomat for the climate. Jennifer Morgan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MORGAN: Thank you. Good to see you again.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth