Pioneer Warren Washington Wins Tyler Prize

Air Date: Week of May 3, 2019

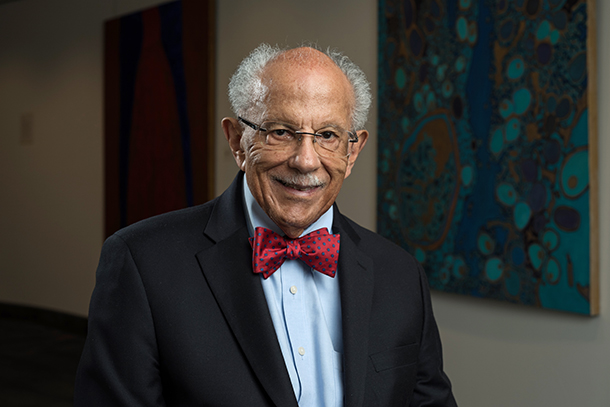

Warren Washington is a 2019 co-recipient of the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn)

Warren Washington, a distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, spent the first years of his more than five-decade career as a key developer of some of the earliest computer models of global climate. A pioneer among African American scientists, he has received multiple awards in recognition of his contributions to the field of climate science, the latest being the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, which he shares with climatologist Michael Mann. Warren Washington speaks with host Steve Curwood about his career, the climate challenge, and leading the way for fellow scientists of color.

Transcript

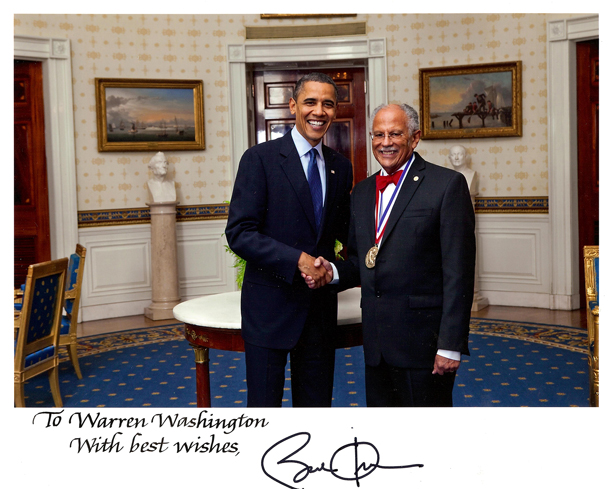

CURWOOD: The world may be moving too slowly to fight climate change, but thanks to good science, at least we have been warned of what’s coming. And today we bring you a conversation with one of the pioneers of climate modeling, who built one of the first models more than fifty years ago and dedicated the rest of his career to improving them. As an African American he was also a pioneer in this mostly white world of science. Warren Washington recently retired from his position as a Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and has received many awards for his work, including the National Medal of Science, conferred by President Obama in 2010. Most recently he was honored with the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement alongside climate scientist Michael Mann. Warren Washington joins me now from Boulder, Colorado. Welcome to Living on Earth, and congratulations!

WASHINGTON: Thank you.

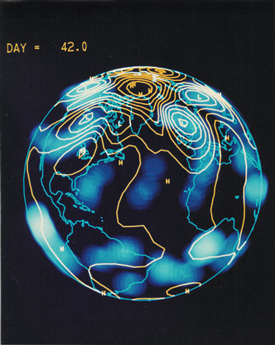

CURWOOD: So you're famous for modeling how the climate works and trying to identify how it's changing. Computing has changed radically since you first started working in weather and climate modeling back in the late 1950s. What was it like to model on those earliest computers?

WASHINGTON: It was very painful. [LAUGHS] Because it took essentially one day of computer time to run one day of simulation. So there was probably a little bit more emphasis on weather computing, because that's just a short two or three weeks at the most. Whereas climate, really you have to do at least a month or so in order to get anywhere. So sometimes it would be very slow. But things happen very quickly, and in the early 60s, in the fact that we were able to implement new computers every year or so. And the newer computers were sometimes two or three or four times as fast. So the technology was catching up.

Warren Washington’s first model, developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the late 1960s. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: Warren Washington, when did you begin to understand how serious the risks of climate change are, and what it poses to humanity?

WASHINGTON: Well, there was an interesting article that Jerry Meehl and I wrote in 1980, and it was published in a journal called Climate Dynamics. Well, the editor of Nature magazine, I believe his name is Maddox, wrote an editorial about our work on climate change. And he thought that this was the real start of a need to define special journals, a Nature series of journals, dealing with climate change issues, and that got us a lot of publicity. Then the other model simulation was in 1989, where we coupled, I think, on the first fully ocean to an atmospheric model, and it was picked up by Newsweek magazine. And John Sununu, who was the chief of staff for the President Bush -- the first President Bush -- said some things in there that weren't quite right in the article. So I sent a telegram to the White House saying, if you need some help understanding, please get in touch. And I was away at a meeting at Stony Brook. And I went home that evening; guess what, there was a call from John Sununu, asking me how I thought he was wrong. And he asked several mathematical questions; turns out he did his PhD at MIT, and he knew some of the numerical methods. So he wanted more details, so I sent him a copy of my book with Claire Parkinson. And I ended up installing a model -- a simple model -- in the White House so that John Sununu could do some experiments. And I spoke with the cabinet of the science agencies and departments. So I spent some time giving advice to him and to the others. As a result, I, over the years I've been an advisor on committees for five presidents.

CURWOOD: What did you take away from your science advising roles for those presidents?

WASHINGTON: I think that even from the very start, when climate change was becoming important, there was a struggle in between the members of the administration and the cabinet and so forth. Some of the members felt that this is a serious problem and they wanted to get started in doing something about it, by taking steps to cut back emissions. And others felt that no, we shouldn't do anything, because there may be an error in the models, or the models aren't quite, aren't good enough. And it comes about by the fact that the oil and gas industry, in my opinion, and the coal industry, has been contributing to one party in our country, more than the other, to essentially not do anything that will slow down the use of fossil fuel energy.

CURWOOD: It's about the money, isn't it?

WASHINGTON: Yeah. Because they're looking for people to sponsor their campaigns.

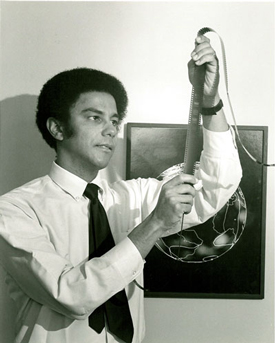

Warren Washington as a young scientist at NCAR. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: I understand that science has been a lifelong passion for you. What drew you to science as a kid, what was going on at home?

WASHINGTON: Early on, I was one of those nerdy kids who wanted to know how things worked. And I was really turned on in my junior year of high school when I had a lady teacher, I think her name was Mrs. Teeters. When I asked her in class, why are egg yolks yellow? She said, Well, why don't you find out? [LAUGHS] And that was intriguing, because that put me on the path of doing a little bit of research -- you know, not actual research in a laboratory, but library research about why egg yolks are yellow.

CURWOOD: By the way, what's the answer?

WASHINGTON: The answer is that there are sulfur compounds in the egg, and that's what you get the orange from. And of course, you know, eggs can, if they're rotten or something, can smell pretty bad. And that's hydrogen sulfide. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I imagine, what, junior year you take physics, is that it?

WASHINGTON: Yeah, I took physics in my senior year, but it was chemistry in my, in my junior year. I eventually ended up going to Oregon State University. And my advisor advised me not to go into science. But to switch over to business, he thought I would have more chance of success. I was pretty stubborn. I ignored his advice and stuck to science.

CURWOOD: Well, yeah, let's talk role models here. You consider yourself African American; how many African Americans did you see around you in the science community?

WASHINGTON: Very few. [LAUGHS] In fact, when I was at Oregon State, there were probably like 10 students or so, African Americans, at the university. I was the only one that wasn't on the football team.

In October, 2010 President Barack Obama named Warren Washington one of 10 eminent researchers to be awarded the National Medal of Science. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: Of course, then as a black scientist, you've not only done this groundbreaking research, but you've broken barriers. I'm looking at a, at a summary of your career that has you as the first black President of the American Meteorological Society, and then you're considered by many to be only the second black person to earn a doctoral degree in meteorology. Talk to me about what it's meant to you to be able to lead the way for other scientists of color.

WASHINGTON: Well, obviously, this has always been a problem of, we're not getting enough diversity in the, in the STEM fields. I've tried to work on that in effective ways. And President Clinton appointed me to the National Science Board, the governing board to the National Science Foundation; I eventually became Chair of the National Science Board. So I had an opportunity to press forward on trying to get programs to deal with the paucity of African Americans and other underrepresented minorities in science and engineering and so forth. I think we've been successful. I think there's real serious attitudes at academic institutions now for a more diverse campus as part of the educational life of universities and colleges. So hopefully, for the next generation it won't be so hard. People ask me, did I encounter a lot of discrimination and so forth? And I did, to a certain extent when I was in grade school, when people would call you names that were very offensive, and so forth. But my parents told me to ignore that, and just keep your eyes on learning, and educating yourself, rather than spend a lot of time in a hostile mood, just because somebody calls you an inappropriate name.

Warren Washington with Tyler Prize co-recipient Michael Mann, a climatologist and geophysicist. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn)

CURWOOD: What gives you hope now, for our ability to deal with climate, to meet the climate challenge?

WASHINGTON: Well, I think the way it's happening now, you can see what's happening in the news. Almost every day, there's some weather or climate issue comes up. And there's a group of statisticians at Yale University that has been carefully taking polls of the public's attitude about climate change. And what is surprising is that 70% of the people agree that climate change is a serious issue, which is much higher than the representation in the Congress. But gradually, the Congress is coming around. I see that the Green New Deal didn't pass in the Congress, but that's just the first step. I see more steps of pushing for controls on fossil fuels by the states. There's real enthusiasm and success being shown as people switch from, you know, fossil fuels to other forms of energy production. And even on the science side and technology side, we're finally learning how to make good batteries, and better batteries using newer technologies. Eventually, we're going to win over, I think, to having a president that's going to really do something. So it may not happen in my lifetime. But it's coming.

CURWOOD: Warren Washington is a retired Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and a winner of the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

WASHINGTON: Thank you for listening.

Links

About the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

Listen to LOE’s interview with Tyler Prize co-recipient Michael Mann

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth