This Week's Show

Air Date: May 3, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

U.S. Funding Fossil Fuels Abroad

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

Despite an international agreement to phase out financing for fossil fuel projects abroad, the Biden administration recently approved a $500 million dollar loan guarantee for an oil and gas drilling project in Bahrain. Nina Pušić of Oil Change International spoke to Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to explain why such actions also hold other nations back from ending this practice (12:21)

EPA Finally Bans Asbestos

View the page for this story

Asbestos is highly toxic to humans and after years of court and congressional battles the EPA is finally banning all uses of asbestos in the U.S. Maria Doa of the Environmental Defense Fund joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss why it took so long and the anticipated public health benefits of the phaseout (06:38)

New Era for Nuclear Power

View the page for this story

The Biden Administration is helping finance advanced nuclear power reactors and refurbishment of traditional nuclear power stations to promote the generation of zero emission electricity. Some of the new designs incorporate liquid sodium to offer more flexibility in power output to an electrical grid where renewable energy is intermittent. MIT professor Jacopo Buongiorno talks with Host Steve Curwood about nuclear power technology and the implications for public health and safety. (20:47)

Coal Transition Bank

View the page for this story

The only coal-fired power plant in Washington state is in the process of shutting down, taking hundreds of jobs with it. But a $55 million fund set up by the coal plant is helping revitalize the small town with community development projects and more. Rachel McDevitt of WITF and StateImpact Pennsylvania reports. (06:58)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240503 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jacopo Buongiorno, Maria Doa, Rachel McDevitt, Nina Pušić

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The Biden administration is investing heavily in zero-emission nuclear power to fight climate disruption, including a new reactor that uses liquid sodium.

BUONGIORNO: Sodium can operate at a higher temperature. So it allows you to actually store the heat more efficiently on site and to modulate the electric power output, so that when the grid demands more power, you can sell more power.

CURWOOD: Also, a failure in Washington to stop financing fossil fuels overseas.

PUŜIĆ: So even though the Biden administration has promised that these, you know, U.S. government agencies would stop funding fossil fuels, U.S. EXIM and DFC have decided that they're going to continue doing that regardless, which presents a lot of big problems, of course.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

U.S. Funding Fossil Fuels Abroad

The official export credit agency of the United States is the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM) pictured above. (Photo: Ben Shumin, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Biden-Harris administration is coming under fire for failing to keep its promise to stop funding international fossil fuel projects. One of those critics is Nina Pušić, senior climate finance analyst with the advocacy group Oil Change International. She laid out her concerns with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: So first let's walk through the basics. What does public financing of fossil fuels entail?

PUŜIĆ: That's a good question. So public financing of fossil fuels is when the government uses taxpayer money through different financial institutions like a public bank or a development finance institution. And then finances fossil fuel projects, fossil fuel being coal, oil or gas. And these public finance institutions in the U.S., there are two, namely, that are relevant to fossil fuel financing. And that's the U.S. Export-Import Bank, which is an export credit agency that supports U.S. companies internationally. And then there's the U.S. Development Finance Corporation that's supposed to help development internationally.

BELTRAN: And how do government subsidies finance fossil fuels?

PUŜIĆ: Yeah. So basically what will happen is, in the case of international public finance, which is the specific type of public finance that U.S. EXIM does, or DFC does, they will get a project, and that project can be from a country, that project can be from, say, for example, ExxonMobil is looking to create a new oil refinery outside of the U.S., like in Indonesia, for example. What ExxonMobil might do is they can go to get a government loan or a loan guarantee through a bank, like the U.S. Export-Import Bank. And they'll go to the bank and submit a project proposal and say, "Hey, we have a great business opportunity here to make a new oil refinery in Indonesia, can you please give us, you know, maybe $100 million in insurance, or $500 million in a loan guarantee.” And there are lots of different types of financial services that they can ask for. But at the end of the day, this type of insurance or guarantee or money that's being given is backed by the U.S. government. So that means that as soon as a project gets funding from the U.S. government, it makes it a lot less likely to fail, because it means that if the project fails, it's actually the U.S. government or the U.S. Export-Import Bank, for example, that onus falls on. So that's why these public finance institutions have such a big impact on the energy industry globally. Because it means that when they choose to support a project, they're signaling to private banks and private financiers that this project is safe to then invest in. So when the U.S. does it for companies like ExxonMobil, it makes other investors be willing to invest in corporations like ExxonMobil. And obviously when it's for fossil fuels, as opposed to renewables, that creates big problems, because then that means that fossil fuel projects become a lot more financially viable than renewable energy projects around the world.

US President Joe Biden. His administration was amongst the 39 governments and public finance institutions that have signed on to the Clean Energy Transition partnership, also known as the Glasgow Statement. In part it promises that by the end of 2022, countries would stop new direct financial support to fossil fuel projects within the year. (Photo: The White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: So, so far, what has the U.S. done or promised in terms of subsidies and loans at the international level?

PUŜIĆ: So at the U.N. Climate Conference in 2021, which was called COP26 in Glasgow, there were 39 governments and public finance institutions that signed on to this initiative called the Clean Energy Transition partnership, also known as the Glasgow Statement. And what they did when they signed on to that initiative is that they promised that within one year, so by the end of 2022, that they would stop new direct financial support to fossil fuel projects within the year. And the U.S. signed on to this promise, it was the Biden administration who signed on, and they made this promise alongside all of these other countries. Unfortunately, while I think there was some intention in the beginning of the Biden administration to actually fulfill this promise and to implement policies at the U.S. Export-Import Bank, and also the Development Finance Corporation, what's happened is that both at DFC and at EXIM they have said that they've decided that this commitment doesn't apply to them. So even though the Biden administration has promised that these, you know, U.S. government agencies would stop funding fossil fuels, U.S. EXIM and DFC have decided that they're going to continue doing that regardless, which presents a lot of big problems, of course, and it wasn't just at the U.N. Climate Conference in 2021 where the Biden administration signed on to this, but it was actually also at the G7 in 2022. So it's not only one but actually two international commitments that this administration made.

BELTRAN: And you mentioned that the United States is amongst multiple countries that have committed to cutting public financing for fossil fuel projects. Tell us more about that.

PUŜIĆ: Yeah, definitely. So there are around 35 other countries that made this promise. And we've seen really good implementation from other countries, say, for example, Canada kept their promise, they implemented a policy a year after signing on to the commitment. The U.K., France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Australia has just signed on to this commitment, and Norway has just signed on to this commitment too. So we have quite a lot of countries that have made this promise and followed through with it. And unfortunately, the U.S. is one of the only countries that hasn't done it yet. But the problem with the OECD is that it's based on consensus. So you need every single country around the table to agree. And unfortunately until the U.S. agrees that means that there can be no progress.

BELTRAN: How are the upcoming OECD talks related to all of this?

PUŜIĆ: So the OECD is the international governing body of all the export credit agencies of OECD countries. And these export credit agencies are the type of agency that the U.S. EXIM Bank is. So as a part of the OECD, the U.S. subscribes to the rules of the OECD are related to export credit agencies, which means that if the OECD has a new rule about what export credit agencies can and cannot do, that means that that would apply to U.S. EXIM as well. And actually, in 2021, when the Biden administration signed on to this commitment, the commitment has two parts. So the first part is that you need to stop funding fossil fuels domestically through your export credit agencies and your development finance institutions. And then the second step is that you need to align yourselves with other like-minded countries that have signed on to this commitment at the OECD, and then make it an OECD rule that applies to all OECD countries. So unfortunately, the U.S. not implementing domestically doesn't only affect the U.S., but it also affects the entire world. Because until the U.S. agrees and puts forward this initiative at the OECD, it means that the rest of the world isn't going to have any binding laws around it. Which is frustrating because we know, given the extent of the climate crisis, that it's really important that countries align their financial flows with climate goals as urgently as possible.

The Bahrain World Trade Center. The U.S. export credit agency approved a $500 million loan guarantee for an oil and gas drilling project in Bahrain, failing to meet their 2021 promise to stop funding fossil fuel projects. (Photo: B. Alotalay, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: And from what I understand, fossil fuel projects are the largest recipients of these credit agency subsidies and loans. What's an example of a fossil fuel project funded by these kinds of loans?

PUŜIĆ: Yeah, the most recent one that the U.S. Export-Import Bank has approved is in Bahrain, which is a wealthy oil- and gas-producing country in the Middle East and the Gulf specifically. And in this case, the U.S. gave a $500 million loan guarantee to new extraction of Bahraini oil and gas wells. So because the U.S. gave these $500 million, which is actually one of the largest projects that we've seen so far in terms of what EXIM has given, in terms of its fossil finance since Biden made this commitment, you now have around 400 new oil and gas wells that are going to be put up because of this loan.

BELTRAN: What about renewable energy projects? What are some of the challenges renewable energy companies are facing when it comes to financing? And how is that being discussed amongst OECD countries?

PUŜIĆ: So kind of one of the key issues around renewable energy financing does actually come down to subsidies and public finance, because what happens is that a lot of these institutions are just so used to subsidizing companies like ExxonMobil, for example, that they haven't really done the outreach to show renewable energy companies how they can apply. Also, a big issue is that because oil and gas tends to be more consolidated in certain regions of the world, say, for example, in the Gulf in the Middle East there's lots of oil and gas, in the Gulf of the U.S. there's lots of oil and gas, but it's not evenly distributed throughout the world, it means that you have a lot of finance going to these very specific places for oil and gas. But for renewables, since you can harness renewable energy anywhere, you basically have to spread that financing equally across the whole world for the energy transition. And unfortunately, there are still a lot of barriers to getting there. But one of the barriers is because, say, for example, banks, like the U.S. Export Import Bank, haven't really done a great job of marketing themselves to renewable energy companies, or they will reject renewable energy projects, because they say that they're not big enough or that they don't have, you know, the right kind of project structure or things like that. It's also almost funny, because sometimes the feedback that we get about why certain banks aren't subsidizing renewables is because renewable projects are actually too cheap, or they're too small. And it's funny, because you would think, "Oh, no, renewable energy is too expensive." But actually, because renewable energy is so decentralized, the projects tend to be a lot smaller, which means the loans that they need are less. So you wouldn't need a $500 million loan necessarily, you might need a $50 million loan. But then a bank like EXIM will say sorry, we don't do $50 million loans. So we can only accept $500 million loans. So therefore, we're only accepting loans from companies like ExxonMobil that do giant, enormous projects, which is yeah, a big challenge because of course, as long as we keep giving these large sums of money away to the fossil fuel industry, it means that we're not getting the financing where it needs to go to renewable energy.

BELTRAN: Walk us through the relationship between EXIM, the U.S. export agency which funds credit energy loans, and Congress.

PUŜIĆ: So EXIM is reauthorized by Congress. So every few years—the next reauthorization, for example is in 2026—Congress says whether or not EXIM can exist. So last time EXIM was getting reauthorized, some Republicans in Congress were really upset that EXIM had implemented anything that was stripped of its coal power financing. And because the OECD agreed to a coal-fired-power ban, it meant that EXIM also had to ban its support for coal-fired power. And unfortunately, some Republicans in Congress really didn't like this, so they got very upset and they almost didn't reauthorize EXIM. So EXIM almost didn't exist anymore, which is why the bank is so paranoid about implementing anything that restricts fossil fuel finance, because they're worried that then in 2026, if Congress is controlled by Republicans, that they basically won't get reauthorized and won't be able to exist anymore.

Nina Pusic is the Export Credit Agency (ECA) Climate Action Strategist at Oil Change International. (Photo: Courtesy of Nina Pusic)

BELTRAN: You know, the Biden administration has only a few months left in office. How much pressure is the administration under to follow through the commitments made at COP26?

PUŜIĆ: Unfortunately, I don't think that the administration feels the pressure quite yet. Because they have really gone very slowly in trying to implement this and trying to put pressure on EXIM. And they also still haven't come up with an OECD position, which is really scary because, as I mentioned a bit earlier, if the administration doesn't get reelected, it's very unlikely that a Republican president would ever agree to something like this at the OECD. Which means that then the whole OECD progress is stalled for the next four years. So the Biden administration has two more chances, one coming up in June and then one in November, and those are the two next OECD negotiations before the election, and it's really important that the U.S. puts forward a position or at least agree as to what other countries have come up with in those two periods. But the clock is definitely ticking.

CURWOOD: Nina Pušić, senior climate finance analyst with the advocacy group Oil Change International, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. We reached out to the U.S. Export-Import Bank but did not get a direct response about the plans for the OECD talks this June. In a press release about the $500 million dollar Bahrain deal, EXIM President and Chair Reta Jo Lewis said: "This transaction will support thousands of U.S. jobs and play a crucial role in ensuring Bapco Energies is able to achieve its climate goals of enhanced grid interconnectivity, more efficiency, decarbonization, and investments in large-scale solar projects.”

Related links:

- Politico | ”‘Rogue’ Agency Backs Overseas Oil and Gas”

- Financial Times | “US And EU Differ Over the Future of Fossil Fuel Subsidies in OECD Talks”

- Learn more about Oil Change International

[MUSIC: Al Hirt, “The Syncopated Clock” on The Happy Trumpet, composer/lyricist Leroy Anderson/ conductor, Arranger Sammy Lowe, RCA/Legacy]

CURWOOD: Just after the break, the EPA finally bans asbestos. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Natalie MacMaster, “Blue Bonnets Over the Border” on In My Hands, MacMaster Music Inc.]

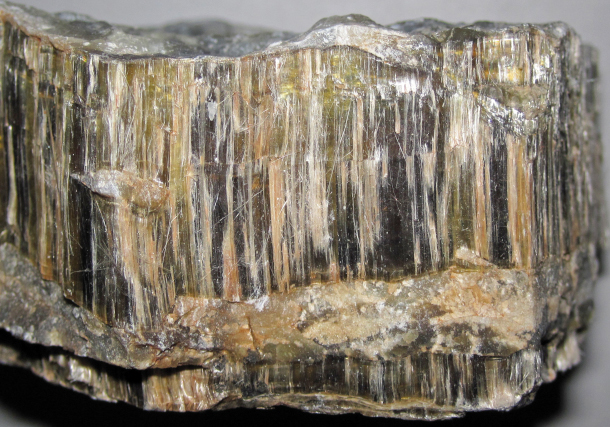

EPA Finally Bans Asbestos

In March 2024, the EPA announced a ban on chrysotile asbestos, the only type of asbestos whose industrial use was still permitted in the U.S. Chrysotile asbestos is used in brake pads, sheet gaskets, and other products. (Photo: James St. John, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

You may have seen the ads on TV. Law firms promising to win millions of dollars for sufferers of mesothelioma, an aggressive and deadly form of cancer linked to asbestos. But only just recently the EPA put in place a broad ban on the industrial use of asbestos, after years of court and congressional battles, interspersed with bureaucratic inertia. Maria Doa. the chemical policy director for the Environmental Defense Fund, put it all in perspective for Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

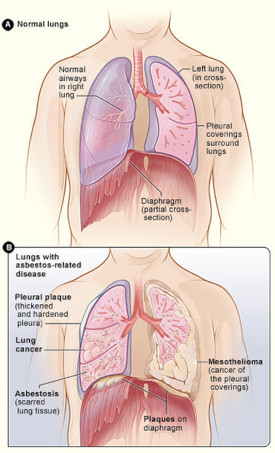

DOERING: What is it about asbestos that's so dangerous?

DOA: It gets deep into your lungs. And it can also get into other parts of the body. But the inhalation toxicity is the issue. And it embeds, and it irritates, and the body's trying to defend itself about it. And the other thing about it, which makes it good for use, is that it doesn't really break down. So it's not like your body can try to break it down and get rid of it very effectively.

DOERING: Now, given the health dangers posed by asbestos, it probably comes as a surprise to some that asbestos had not already been banned in the U.S. How important is this announcement?

DOA: It's extremely important that EPA is finally banning chrysotile asbestos, which, as you noted, is still used in industry, and also in some consumer products, including aftermarket brakes. So there's a potential for exposure from all these uses. So it's really important that the door is finally going to be closed on this very deadly chemical.

DOERING: How did we get to this point? What happened?

DOA: Well, EPA actually did try to ban asbestos in 1989. But there was a court case, and EPA lost most of the case, and so many of the uses of asbestos were still allowed to continue. One bright spot of that case, though, is that any new use of asbestos was precluded from starting up, and there were some uses of asbestos that did survive the court case and were banned.

Asbestos exposure has been linked to mesothelioma, lung cancer, and other health issues. (Photo: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DOERING: So a federal judge blocked the EPA from banning asbestos when it tried to do that 30 years ago. What was the argument against the ban at that time?

DOA: Part of this is due to the fact that the primary law that governs toxic chemicals in this country, known as the Toxic Substances Control Act, at the time had a requirement that EPA do a cost-benefit analysis, and also that it choose the least burdensome option for managing the risk. And the least burdensome option for some of these cases was in the eye of the court, unfortunately, and so they could continue. In 2016, Congress amended the Toxic Substances Control Act and took away the requirement to do a cost-benefit analysis before it banned anything and to look for the least burdensome option. And had EPA make the determination based on risk, which is really important for a toxic chemical like asbestos. So EPA was able to go forward with asbestos and a number of chemicals, very toxic chemicals, and take action on addressing the significant risks associated with these chemicals. And asbestos is the first one that was finalized this action.

DOERING: So Maria, TSCA was amended during the Obama years. Why did it take eight years for this ban on asbestos, the first ban under that amended law, to be announced?

DOA: Well, work started on it immediately after it was passed. And subsequent to the Obama administration, when the Trump administration came in, banning these chemicals or limiting these chemicals were less important. And they were actually sued over the approach that they were taking that was so narrow, so it's taken a little bit of time to get back on track and move forward on trying to manage the risks from these chemicals.

DOERING: So now that asbestos has been finally banned, what are some of the other potentially harmful industrial chemicals being targeted by the EPA?

Although the U.S. banned asbestos in 1989, a 1991 appeal weakened the regulation so that it did not cover all uses of the substance. (Photo: Nick Southall, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOA: So a couple of the chemicals in particular I'd like to highlight. One is a chemical known as trichloroethylene, or TCE. It has a number of uses. An important one is degreasing. TCE is of significant concern because it causes multiple types of cancer. It causes effects to pregnant women. It causes cardiac malformations, causes effects on the immune system, so it causes a broad range of effects and at very low levels. It affects multiple organs in the body. So EPA has proposed to ban most uses of that chemical. And the other chemical I would like to highlight is a chemical known as methylene chloride, which is a chemical that has historically been used as a paint stripper. And there have been a number of deaths from the use of methylene chloride as a paint stripper. And EPA did ban the use of it for consumers several years ago, but they've now proposed to ban most uses commercially and industrially. And it's important to remember that these commercial uses, which include bathtub refinishing, people had used it for baptismal fonts and there had been a number of deaths associated with that. So this is also an extremely important step forward.

CURWOOD: Maria Doa. chemical policy director for the Environmental Defense Fund, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Read the EPA’s news release about the ban on chrysotile asbestos:

- AP News| “EPA bans asbestos, a deadly carcinogen still in use decades after a partial ban was enacted”

- More on asbestos and its health effects from the EPA:

- Maria Doa’s profile on the EDF website:

[MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “Low in the Grave He Lay” on Parlor Guitar, by Robert Lowry/public domain, Fossil Records]

New Era for Nuclear Power

TerraPower’s Natrium reactor, which uses liquid sodium as a coolant, is designed to vary its power output depending on demand. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Half of the zero-emission electricity generated for the grid in the U.S. comes from nuclear reactors, and the Biden-Harris administration is aiming to triple nuclear power generation by 2050. The Inflation Reduction Act and other federal funds are providing billions of dollars in loan guarantees to help existing nuclear power plants upgrade to stay in business. Billions more are being deployed to support advanced nuclear reactor designs, from small ones that can use breeder type reactions and theoretically never run out of fuel, to large ones that use liquid metals like sodium as coolants to boost efficiency and flexibility. The administration’s nuclear power program also promotes using locations where coal fired plants have retired. TerraPower, founded by Bill Gates, is using such a site in Kemmerer, Wyoming where it aims to build its sodium-based reactor. Jacopo Buongiorno is a professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT, and joins us to discuss these developments. Professor Buongiorno, welcome to Living on Earth.

BUONGIORNO: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So in the face of the climate emergency, we have to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels as quickly as possible. So to what extent can nuclear energy play a role in our urgent race to decarbonize?

BUONGIORNO: Nuclear can play a big role, already plays a role, roughly half of our low carbon, or clean electricity at the moment in the United States comes from nuclear. So it already is a big part of our clean energy infrastructure. It can play even a bigger role, and not just on the grid. If you look at the amount of CO2 emissions across all sectors of the economy, the power grid only accounts for roughly one quarter. And what that means is that we need energy technologies that can replace the use of fossil fuels, not just on the grid, but on things like transportation, industry, agriculture, buildings, etc. And the nice thing about nuclear is that it's a fairly versatile energy source. It can give you heat, if you want heat. It can give you electricity if you want electricity. It can give you hydrogen if you need hydrogen, or some kind of synthetic fuel for transportation, so potentially a very, very big role.

CURWOOD: So Professor, can we have a bit of context here? Compared to the nuclear power plants that are online in the United States right now, what's new or revolutionary about TerraPower's Wyoming plant?

BUONGIORNO: That's a great question. The reactor itself is really a different design from the 90-plus plants that are in operation at the moment in the United States. Those plants use water, perhaps the simplest fluid that we can think of as the coolant inside the reactor, whereas the new TerraPower plant will use liquid sodium, a liquid metal, as the coolant. It's not an entirely new concept. As a matter of fact, it has been, you know, proven, tested in the United States many decades ago, in France, in Russia, but it never sort of caught up commercially. And so now it's coming back, thanks to Bill Gates' company called TerraPower.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the design of this reactor. Sodium is used to cool the reaction. But I gather it's used for a lot more. What's going on here?

BUONGIORNO: So a nuclear reactor is a heat source. The nuclear reaction that takes place within what we call the core is called nuclear fission. The product of that nuclear fission is heat. And the first order of business in a nuclear reactor is basically to take that heat from the reactor core to another section of the plant where that heat is typically converted to electricity, because that's what you sell to the grid. Sodium is used as the circulating fluid within the reactor core to do just that, right, to move the heat from the core somewhere else within the plant. And it happens to be very efficient, more efficient at that job than water. And because of its thermodynamic properties, if you will, sodium can operate at a higher temperature, so it allows you to actually store the heat more efficiently on site, and to modulate the electric power output so that when the grid demands more power, you can sell more power. When the grid demands less power, you can basically keep storing the heat on site and selling that power later. So it's the ability of basically swinging up and down in power output that is allowed with this particular reactor design that would be more difficult with the traditional designs.

Bill Gates is Founder and Chairman of TerraPower. (Photo: Billionaires Success, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's the advantage?

BUONGIORNO: This particular feature is important these days, because there is a lot of variability on the grid for two reasons. First, because well, the demand for electricity on the grid is not constant, since people switch on their appliances in the morning, and then in the afternoon, you know, there is sort of peaks and valleys created by demand. But there is also quite a bit of variability on the grid because of the penetration of intermittent renewables like solar and wind. Sun doesn't always shine, wind doesn't always blow. So you have sort of again, ups and downs in what's generated, what the electricity is generated on the grid. And so this reactor, which is able to vary its power output, is particularly useful in that context.

CURWOOD: So you have a thermal battery with this design, so that you can store extra heat and use that to make electricity when you want to. And meanwhile, the reactor itself is creating a whole bunch of heat.

BUONGIORNO: That's a great way to put it. And in principle, you could change the amount of heat that is generated from the reactor itself. But that's not economically very attractive because a nuclear reactor, a nuclear power plant is essentially an expensive machine that burns cheap fuel. What that means is that it takes a lot of money to build the plant, and it doesn't take a lot of money to run it, to operate it. The implication of this is that once the plant is built, you want to always run it at 100% output. And again, this sort of is designed with liquid sodium allows you to keep that heat output constant, but to vary the electric output on the grid. And the location matters. This particular plant in southwestern Wyoming is located on a major transmission line that connects that site to California. California, again, is obviously a very big power market to begin with, but also a lot of variability because of their reliance on solar and wind. So the plan for this nuclear power plant in Wyoming is to sell significant amount of its electric output to California via that transmission line.

CURWOOD: This plant is being built where a coal fire plant once was, I guess that puts it at a good connection for the grid. What other advantages to being where a coal-fired power plant was?

BUONGIORNO: Many advantages, starting with the fact that communities that were relying on the economic footprint of those coal-fired plants now find themselves in a position to benefit from the new plant, right? So it’s jobs, it's tax revenues, it's overall economic impact. But strictly speaking from the point of view of the plant itself, you can reuse transmission lines, which we've already mentioned, you can also reuse cooling infrastructure, as well as access roads, administrative buildings. And lastly, the workforce has to be retrained because a coal plant is not the same as a nuclear plant. But in fact, a nuclear plant, everything else being the same, typically employs more people than a coal fire plant. So several advantages there.

TerraPower’s nuclear plant will be built near the site of a retiring coal plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming. (Photo: Jimmy Emerson, DVM, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What public health advantages are there from this approach?

BUONGIORNO: That's another good side of the story, you know, coal fire plants, they've been keeping the lights on for decades, but they're now going out of business because of their environmental impact. They emit a lot of CO2, and it's a greenhouse gas, so it's associated with climate change. And so a reduction of those emissions is very, very important. And number two, if you just look cold blooded at number of casualties per unit electricity generated, even if you calculate the number of people that have been harmed by radiation in accidents, which is a very, very small number, there is no comparison. Coal plants unfortunately kill scores of people. In addition to CO2, they spew out in the atmosphere a lot of particulate and a lot of criteria pollutants, which cause respiratory problems. So as coal plants go out of business and are replaced by nuclear power plants, which don't have any such emissions, the quality of the air locally should also improve.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a lot of talk that this plant's reactor has a safer design than the current light water reactors. Your response?

BUONGIORNO: My response is, current light water reactors are extremely safe. They have a very good record. I wouldn't characterize these as safer, I would say it has a different safety approach. A vast majority of the reactors that we have been operating for the past few decades rely on what we call active safety philosophy. What that means is that if there is a failure or a malfunction, there is a number of engineer systems, powered by external energy sources, things like diesel generators or batteries or whatever it is that is required, to ensure that those engineer safety systems operate properly. That approach works, and it realizes a very, very safe system, but it's fairly complicated because it requires operator action, it requires to maintain those engineer safety systems in good shape. So there is cost and there is complexity associated with it. All the new reactor designs that are being contemplated now, including TerraPower, TerraPower is no exception, use a different safety philosophy or a safety approach, which we call passive safety. They don't rely on external energy sources to drive the safety systems. They rely on things like thermal siphoning, you know, natural circulation, gravity, pressure differences. So phenomena, physical phenomena that don't require an external input of energy from diesel generators, batteries, pumps or things of that type. What that means is that if there is a malfunction or a failure of components within the plant, even in case of a major disaster, like an earthquake, tsunami, a fire, terrorist attack, whatever it is, the operator, human operator does not have to intervene, does not have to launch the engineer safety systems. The safety systems would be able to run on their own, and so the expectation is that this overall is going to make for a more reliable, a more robust, a more human-error-tolerant system. So safe in both cases, just different approaches.

TerraPower’s variable output concept is designed to pair well with intermittent renewable energy sources. (Photo: John Morton, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Ohana Kai (Family of the Sea)” on Musings-Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, self-published]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, we continue our conversation with MIT professor Jacopo Buongiorno, and ask the question, what about the nuclear waste…. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Goldspiel Provost – Classical Guitar Duo, “Danzas Espanolas - Villanesca” on Latin Magic, by Enrique Granados, gpd Records]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We are back now with MIT nuclear physics and engineering professor, Jacopo Buongiorno.

I don't have statistics, but I know anecdotally, when one talks with people about nuclear power, inevitably they say, what about the waste? So what do you say?

BUONGIORNO: Yeah, waste has been a tough issue for nuclear all along, it still is, at least in the United States, simply because we don't have what people call the ultimate solution, the ultimate disposal site, okay? So first of all, what we call waste is really the spent fuel, it's the fuel that comes out of the reactor, which has sort of run out of juice, run out of its energy content, and it's become highly radioactive, okay? So what's done at the moment in the United States is we keep it very safely stored at the site, first in spent fuel pools, in water pools for several years. Radioactivity naturally decays, so its radioactive levels, so to speak, go from very high to significantly lower within a couple of years. And then they are moved from these pools into what people call dry casks. So these are canisters made of steel and concrete, highly engineered and well shielded. And at the moment, we have basically this material at the individual nuclear power plant sites. It is safe, it's relatively cheap to manage, we can continue to do this for decades. But eventually, all that material's got to go somewhere, it's got to be consolidated. The consensus is that it has to go underground. It's what people call a geological repository. And the issue we have in the U.S. is that we've been unable to find a site anywhere in our big country that will host that final repository. I keep saying “in the U.S.” because other countries have solved the problem. And the first country that is actually going to open a geological repository is Finland, that should happen either next year or the year after, between now and 2026. So they have a different political process, general public has a higher level of trust in their government. It's all about that. It's not a technical problem, it's never been really a technical problem, it's always been an issue with how you manage the process that leads to the selection, authorization, construction, and finally, operation of a geological repository.

Coal plants emit both toxic particulate matter and greenhouse gases like CO2. Comparatively, nuclear plants do not have the same emissions. (Photo: Duncan Rawilson - Duncan co., Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Professor, what's the volume of so-called nuclear waste right now in America? How big a space would it occupy if it were consolidated?

BUONGIORNO: That's actually one of the positive attributes about nuclear. It doesn't produce a lot of waste. And that's because the energy content of the material that we use as fuel, which is called uranium, is extraordinarily high. I mean, that's always been sort of the attractive feature of nuclear is that it doesn't require a lot of fuel to generate a lot of energy. The implication of this is that you also don't generate a lot of waste. Just to give you an idea, if a person like me and you were to use only nuclear energy, only nuclear electricity for all our life, the amount of spent fuel that we would produce would basically fit within a cup of coffee. Now, there is a lot of us. So if we all use nuclear energy, of course, the cups of coffee add up. But to give you another example, all the spent fuel, all the waste that we have produced now in the United States, over the past sixty years of operation of 100 reactors generating roughly 20% of our electricity, if consolidated, would basically fit on something that looks like a football field, for all the United States past sixty years, 20% of electricity. So the volumes are not large, but we got to put it somewhere. And that's been the challenge.

CURWOOD: Professor Buongiorno, do you want to briefly talk about breeder reactors and what might be done with so-called spent nuclear power plant fuel?

BUONGIORNO: So at the moment, the approach that we use in the United States, so called once-through fuel cycle, so the idea is that once that spent fuel comes out of the reactor, it's going to be disposed of, it's not going to be reprocessed, recycled, but it's interesting that you should ask because if you look from a technical point of view at the contents of that spent fuel, some of it is waste, but most of it still has a potential use as fuel in other reactors. And so you call them breeder reactors. A sodium-cooled reactor can be designed to be a breeder reactor. Breeder reactor is going to sound a little bit like magic, but it's not. It's a reactor that actually produces more fuel than it consumes. And it's done through the bizarre laws of nuclear physics and quantum physics. But it does work. It's not science fiction. It's very, very solid science. And so you can use the part of uranium which is our fuel, that is not utilized in traditional reactors, and turn that uranium into plutonium, which is good fuel for the breeder reactor itself. And so again, through a nuclear physics process, you can actually make more fuel than you're consuming. They were very much in vogue back in the 50s and 60s when people thought that we would run out of uranium and so there would be a need for sort of multiplying the utilization of uranium. We know now that uranium is very widespread on Earth, and it's pretty cheap. So I would say they've fallen out of favor, at least the United States, but there are other countries, Russia and China in particular, and even France, that are long-term committed to this idea that you could use breeder reactors.

According to Professor Buongiorno, US nuclear power produces such a very low volume of radioactive waste all such waste produced in the last 60 years could fit in a single football field at a depth of about ten feet. (Photo: Green MPs, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about all the atomic weapons that people would like to see decommissioned? To what extent might that help the fuel situation for nuclear power reactors?

BUONGIORNO: Well, it did. There was a program that I think ended just a few years back, it was called megatons to megawatts. And under that program, a lot of the idea of rich uranium that was producing Russia for weapons, for nuclear weapons, was converted to lower enriched uranium and used in reactors around the world, in particular in the United States. So a lot of the warheads that were decommissioned under treaties between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union, and then Russia have actually, that material has made its way into the commercial domain and is being used that way. So if the great powers, shall we say, the great nuclear powers, U.S., Russia, and China decide that they want to reduce their arsenals, this scheme can be implemented again. But I don't need to tell you, Stephen, at the moment it's not looking particularly good on the international scene, right? The geopolitics are such that, if anything, I think we might see an increase in nuclear weapons, unfortunately.

CURWOOD: So what's the current public opinion about nuclear power? How do people feel about its safety and viability?

BUONGIORNO: Well, the interesting thing is, at least in the United States, the support for nuclear has always been pretty high. And when I say always, I mean, over the past 20 years, including just following the Fukushima accident. At the moment, it's at an all-time high, I've been in this community for 27 years, and I've never seen sort of numbers as they are now, I think low 70s. That's generic support by the public in the United States. I'm always sort of hesitant to translate that to, how can I say, solid support, either for nuclear or anything else, right? So there is a difference between generically supporting something and then supporting it when that something becomes a project in your town, in your county, right? There is the NIMBY, "not in my backyard" syndrome. And so, by the way, this applies to all technologies. You know, if you look at the support for solar and wind, it's off the charts, good, right? Everybody likes solar and wind. But then you look at the realization of big solar, wind, and transmission line projects in United States. And they keep running into serious issues of authorization and opposition from locals. And I would expect that if there was a push for a widespread increase of nuclear power plants around the United States, especially in new sites, sites that don't already have nuclear power plants, we might see a little bit of the same NIMBY response, but in general, it seems to be doing okay. And of course, it's also geographically dependent. Some states are more supportive than others.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what's going on with trying to put a reactor that was closed a while ago in southwest Michigan back online. What's the story about that?

BUONGIORNO: Yeah, that's the Palisades nuclear power plant, single-unit pressurized water reactor, I think it's about 800 megawatts. It's relatively large, had been in operation for several decades, it actually had obtained a license extension from 40 years to 60 years, but for economic reasons, the company that owned it, used to own it, Entergy, decided to shut it down. But there was nothing wrong with the plant, it simply wasn't making money. And that site was purchased, literally, by another company called Holtec, which immediately decided that they would like to actually keep it up and running. And I think what what changed since the decision of the previous owner to shut it down and the decision of the new owner to restart it is, well, many things, most important of which is maybe prices have gone up for electricity. So what used to be economically not attractive now is economically attractive. But perhaps more importantly, the desire to reduce emissions. We've seen many, many times in the United States that when nuclear power plants shut down, the emissions in the state or states where they are located typically shoot up very, very quickly. So there is the environmental concern. And once again, there is the economic concern in terms of economic footprint locally. So there is a lot of good support by the state of Michigan. And as we learned last week, also good support by the federal government in the form of a loan of about $1.5 billion. So the schedule there is such that the plant should restart in 2025, so a year from now.

Jacopo Buongiorno is a professor of nuclear engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (Photo: Courtesy of Jacopo Buongiorno)

CURWOOD: So to what extent do you think that this new TerraPower plant will spark a new era for nuclear energy? How's it going to deal with the present obstacles facing the nuclear energy power market here in the U.S. today?

BUONGIORNO: Well, I don't think it's one size fits all. In other words, while I like that project, I don't think it's just going to be that project that will propel nuclear forward, so to speak. It is an important part of it. It does address the question of increasing the economic attractiveness of nuclear on the grid, and again with the idea that you can vary your power output while maintaining sort of that full utilization of your reactor, that's a smart approach. So that's new. And if that's proven successful, I think that model might be followed. But there are other projects that are ongoing. They're all, in many ways, equally important because they address different applications, different sectors of the economy. So I think it's going to be a combination of these projects that will determine if nuclear is going to be successful or not in the U.S.

CURWOOD: Jacopo Buongiorno is a professor of nuclear science and engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BUONGIORNO: My pleasure.

Related links:

- TerraPower | “TerraPower Submits Construction Permit Application to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission for the Natrium Reactor Demonstration Project”

- Learn more about the U.S. Nuclear industry

- Learn more about U.S. Nuclear Plants

- Department of Energy’s Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program

- AP News | “Biden Administration Will Lend $1.5 B to Restart Michigan Nuclear Power Plant, A First in the US”

[MUSIC: The Contribution, “This Too Shall Pass” on Wilderness and Space, by Tim Carbone/Phil Ferlino/Jeff Miller, Lo Hi Records]

Coal Transition Bank

This Lewis County Transit electric bus was purchased with grant funds from TransAlta. (Photo: Jeremy Long, WITF)

CURWOOD: Not every community can replace the jobs lost when a coal fire power plant shuts down, but Centralia, Washington has found a way to try. 13 years ago its coal burning utility agreed to close by 2025 and give $55 million to help the community make the transition. Those funds now support new energy technology, community and economic development and energy efficiency. Rachel McDevitt of radio station WITF in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania went west to report on the progress so far of some of the funded projects.

CLARK: So this bus is charging, and that's a fan that keeps the batteries cool and the charging equipment cool.

McDEVITT: Joe Clark heads up Lewis County Transit, which serves the Centralia area. He's showing off the electric charging station made possible with a grant from the Coal Transition Fund, the $55 million put up by power plant owner TransAlta to help the area deal with the loss of the plant next year. Clark's not stopping at electric buses. He jumps in his car and drives to a vacant lot in an industrial park about 15 minutes outside town.

CLARK: Really cool green field, you probably wonder why I stopped here. This is where our hydrogen facility's going.

McDEVITT: He hopes this is the future of transit. Clark just accepted delivery of the first hydrogen-fueled buses in Washington. The state is trying to develop a federal hydrogen hub powered by renewable energy. TransAlta gave the transit company nearly $2 million to build an electrolyzer right here, part of the new energy technologies fund that will use electricity to split water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen.

CLARK: For longer range in rural America or rural Washington where we are today, we have to use hydrogen, because the battery electric just won't get us there.

McDEVITT: The company has ordered equipment to build a fueling station where US 12 meets Interstate 5. This point about halfway between Seattle and Portland could be a convenient place for trucks to refuel. Clark sees a hydrogen buildout as a way to attract companies that want to use hydrogen and create cool new opportunities for people here. He says this area suffers from brain drain. Kids who head off to college often don't come back because the kinds of jobs they want aren't here.

CLARK: And we're really hoping that this effort will bring a series of jobs that are not only interesting and engaging and attractive, but are well paying.

McDEVITT: A new clean energy economy that might bring direct job replacements for workers at the closing coal plant is only one piece of the transition fund. A chunk devoted to community development has gone to educational programs. Some focus on science, math and engineering to prepare kids for future jobs or college. Others prepare students to handle challenges in different ways.

The Onalaska High School hatchery program boasts a tank full of rainbow trout. (Photo: Jeremy Long, WITF)

HOFFMAN: Right here we have some rainbow trout.

McDEVITT: About half an hour from Centralia at Onalaska High School, Kevin Hoffman teaches career and technical education courses like woodshop, metalwork, and aquaculture. Hoffman applied for and got two TransAlta grants to raise the school's fish hatchery program to one that rivals commercial operations. When he started, the program was raising about 1,000 pounds of fish.

HOFFMAN: Now we can almost raise about six to 7,000 pounds of fish.

McDEVITT: Students do everything from feeding fish to constructing the new hatchery, a 24-by-70-foot low metal building. Hoffman says some students sign up for this class looking for an easy science credit, but they end up doing more math than they bargained for.

HOFFMAN: We're able to calculate it out and say hey, we want the top largest 300 fish, and now we know that okay, those are all the fish over, say, 34 centimeters we need to keep and pull out.

McDEVITT: Down at Carlisle Lake where adult fish are released, Hoffman says he's trying to teach the kids to ask, how can we make this better?

HOFFMAN: How diligent do you have to be with your your daily feeding, your daily water quality checks, your disease management, all of that stuff. So just trying to teach the students to think outside the box, being efficient, coming up with new ideas, problem solving.

McDEVITT: Every year, the students release up to 10,000 trout that can be caught and taken home. About 600 are between six and eight pounds, making for an exciting opening day of fishing season.

After the fish are raised at the Onalaska High School hatchery, they are transferred to the Carlisle Lake nets. (Photo: Jeremy Long, WITF)

HOFFMAN: And it's a zoo. We've had people come from Seattle, Portland, Wenatchee, which is the other side of the mountains, like four- or five-hour drive.

McDEVITT: It's important to Hoffman that the program gives back to the community like this. It's a similar story for Levi Althauser in downtown Centralia.

ALTHAUSER: I think that if you don't know the people you live next to, then you're not really living a full life.

McDEVITT: Levi and his wife Sarah started the Juice Box Public House because they wanted a new family-friendly social space, like the rural granges that their grandparents went to.

ALTHAUSER: Like all the dances they used to go to, all the activities they used to do that they'd stay up ’til 2 am, have a midnight dinner and then go back to dancing for another two hours with kids.

McDEVITT: The Althausers bought the building, an old Elks Club, in 2019. There's a bar in the front with plush chairs and a few high-top tables. Local artwork hangs on the walls. The back room has a big stage. Decorative blown glass is suspended from high ceilings. A huge elk head named Arthur hangs above the entrance. It's a cozy blend of modern and rustic with long cafeteria-style tables.

ALTHAUSER: And so if you're a couple, a lot of times you sit at one end, and you can tell, like people feel a little bit awkward, like, “I don't know if I should sit too close to you,” but that's what we're trying to do, is get people to sit with strangers that will then next time not be strangers anymore.

McDEVITT: It would have been a short-lived venture without a weatherization grant from the transition fund.

ALTHAUSER: So anywhere where you see a brown spot, which is pretty much everywhere, is where another leak started. And so we were going crazy trying to cover leaks. We--we covered the whole roof in plastic and still had all of the leaks coming through.

McDEVITT: They replaced the roof and failing heating system. The money came from the weatherization pot, even though the outcome benefits community and economic development. Althauser says it was a huge help as he entered into the notoriously profitable business of a music venue.

ALTHAUSER: It's not a wise financial investment, but it's a good community investment.

McDEVITT: The Althausers hope that Juice Box is part of what makes Centralia a good and fun place to live and gets more people and businesses to call it home. TransAlta has been a big community partner, donating to the community college, the United Way, and other nonprofits. It helps support a middle class that could come together to support the community. Even as that company shuts down, the fund it made is helping Centralia forge ahead on its own. For Living on Earth, I'm Rachel McDevitt.

CURWOOD: Rachel’s story comes to us courtesy of WITF and State Impact Pennsylvania.

Related links:

- This story on the StateImpact Pennsylvania website

- StateImpact Pennsylvania

- 89.5 WITF

[MUSIC: Chris Pandolfi, “Open C” on Looking Glass, by Chris Pandolfi, Sugar Hill Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org.

I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Creating positive outcomes for future generations.

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live. Listen to the race to 9 billion

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth