This Week's Show

Air Date: February 6, 2026

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Law and Environmental Justice

View the page for this story

The National Academy of Sciences has found black people are exposed to 66 percent more pollution than they produce, while white people are exposed to 17 percent less pollution than they create. In honor of Black History Month Special we highlight some of the voices that stood up against environmental injustice including Civil rights activist the Rev. Dr. Ben Chavis, and Dr. Robert Bullard who’s been deemed the “Father of Environmental Justice,” And in a conversation with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran we also look back and look forward at prospects for breaking the chains of environmental racism with long time environmental lawyer and activist Monique Harden. a trail blazer in addressing problems of people and pollution in Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley”. (14:15)

The Power of Black History

View the page for this story

The burial of a nine-year-old enslaved girl on a plantation in Louisiana may halt construction of a new petrochemical plant on that land in the state’s “Cancer Alley.” Many descendants of enslaved people in the region already live with health problems from exposure to industry and are looking to their ancestors to stop further expansion. Lenora Gobert, a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. (16:57)

The Quest for Env. Justice in Shiloh Alabama

/ Melissa WilliamsView the page for this story

For black history month we bring you a cautionary tale brought to us by the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media or CEJM. CEJM helps people of color learn how to tell their own stories in the face of environmental injustice and the climate emergency. Melissa Williams is a storyteller for CEJM and she shares her community’s efforts and concerns as they seek justice from the State of Alabama after highway construction flooded their homes in Shiloh Alabama. (15:39)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

260206 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Lenora Gobert, Monique Harden

REPORTERS: Nana Mohammed, Andrew Skeritt

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Environmental justice history to see ways forward.

HARDEN: The decisions that got us into this were decisions that did not value people, did not respect human dignity or human rights. And so that means our solutions have to be really wrapped around human rights and dignity and a sense of how special future generations are.

CURWOOD: Also, the history of enslaved people in Cancer Alley.

GOBERT: The fact that this area is considered so vital to the US economy, that this heavy industry must be sited there means that they will do pretty much anything that they need to do to overlook the fact that there are human beings who were buried all along the river, there are thousands of these burial sites.

CURWOOD: It's the Black History month special on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Law and Environmental Justice

Dr. Robert Bullard, a pioneer in the movement for environmental justice, speaks at the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media (CEJM) Conference at UMass Boston in September 2025. Dr. Bullard is founder of the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice at Texas Southern University in Houston, and author of Dumping In Dixie, (1982) the first of more than sixteen books he has published about environmental racism. His most recent is The Wrong Complexion for Protection (2018). (Photo: CEJM)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Today our program is a special for Black History month, and the theme is environmental justice. Just to be clear, you don’t have to be African American to suffer from environmental injustice.

CURWOOD: In fact the majority of the 300,000 or more Americans who die every year from burning gas, oil and coal are white, and few argue it is fair for anyone to die from pollution. But the National Academy of Sciences has found Black people are exposed to 66 percent more pollution than they produce, while white people are exposed to 17 percent less pollution than they create. Here's sociologist Dr. Robert Bullard, one of the architects of the environmental justice movement.

BULLARD: America is segregated and so is pollution. There’s no reason why the asthma death rate for Black children is eight times that of white children. And a lot of it has to do with what’s in those neighborhoods, and the extent to which people have access to healthcare, and in terms of polluting facilities and all of that coming together. When we talk about environmental justice and the birth of our movement, it’s always been about health. Physical health but also mental health.

BELTRAN: For generations, African American and other communities of color have been exposed to higher levels of pollution from landfills, chemical plants, and highways. Back in 1979 Robert Bullard started to document this history of contamination and the placement of especially dirty dumps and industry closer to brown people and further from white people as facts for lawsuits. And in 1982 Civil rights activist the Rev. Dr. Ben Chavis led the fight against the dumping of PCBs near the Black neighborhoods in Warren County, North Carolina.

CURWOOD: By the way, PCBs are in the same family of chemicals as dioxins, which can be persistent and highly toxic, causing cancer and other diseases. Rev. Chavis is credited with first coining the term “environmental racism” during those North Carolina protests.

Rev. Dr. Benjamin Chavis, who served as North Carolina’s statewide youth director for Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference is a journalist, author, civil rights activist and president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association. He spoke at the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media (CEJM) Conference at UMass Boston in September 2025.(Photo: CEJM)

CHAVIS: I've seen communities organize, resist and rise up from the Amazon to the Arctic, from the Pacific Islands to the inner cities of America, people are declaring with one voice, environmental justice is not only a civil right, environmental justice is a human right. So we are called to action for the next generation.

BELTRAN: For years research has documented the disproportionate impact on people of color of environmental risks such as toxic exposure, the urban heat island effect and other dangers from the climate emergency. In 2021 protests and social concerns finally spurred action by the Biden Administration and Congress to allocate billions of dollars to remediate the short-changing of environmental protections in under-served communities.

CURWOOD: But that ended under the Trump administration. Likening the Biden-era environmental justice policies to reverse discrimination, the Environmental Protection Agency has now cut grants and rolled back regulations designed to improve environmental quality in both white and Black communities.

BELTRAN: And among the hardest hit are African American enclaves, like those along the highly industrialized Cancer Alley in Louisiana. As part of Living on Earth’s Black History Month Special we are looking back and looking forward at prospects for breaking the chains of environmental racism. Joining us from New Orleans is environmental justice lawyer and advocate Monique Harden. Monique, Welcome back to Living on Earth!

HARDEN: Thanks. It's great being here again.

BELTRAN: The environment, environmental justice is facing a tough time right now across the United States. How can people in the US hold polluters accountable at a time when the federal government is dismantling Environmental Enforcement regulations?

HARDEN: Sure. So I think one of the things people should first take a breath that you can have some really positive outcomes in terms of community health, in terms of environmental justice, with this current administration that is really ripping some of the guardrails that were expected for environmental consideration. One area to then bring focus to is what can be done at those local, county, and, perhaps, state levels of government. You can have a state issue a pollution standard that's more stringent, more protective than a federal standard. You can have a land use decision from a parish government to deny turning a residential or an agricultural zone into one for heavy industrial development, you know, polluting facilities. And so, bringing the fight to areas of government where there might be opportunities to achieve environmentally just results is an important thing to do because each victory that can be achieved can be looked at when the opportunity comes again for new federal standard setting.

The Rev. Dr. Benjamin Chavis is credited with coining the phrase “environmental racism” during protests over PCB dumping in Black communities in Warren County, North Carolina in 1982. (Photo: CEJM)

BELTRAN: Now President Trump has called environmental justice “reverse discrimination.” What's your take on that issue?

HARDEN: This is an administration that wants to promote racism. People around the country have and are rejecting that, whether it's environmental justice or other issues, the way in which people are organizing and making a difference with their local leaders together.

BELTRAN: And you're an attorney, and a lot of your career has focused on environmental justice. How did you get involved in this work?

HARDEN: I always saw communities as a place for enjoyment of where, you know, people coming together, sharing experiences, stories, looking out for each other, and as I grew into adulthood, I knew that I wanted to be a lawyer. I wanted to work for justice. Having an opportunity as a law student to work in, on environmental issues and seeing the racial disparities that were just blatant, and it was just jarring to see, you know, folks trying to make a way and suffering every day from pollution and having no voice in the decision that placed that toxic smokestack, toxic industrial facility in their midst. It was very easy connection, you know, seeing the thing that I love about communities really being attacked by decisions that allowed this kind of heavy toxic industrial growth and pollution to be present in a way that is life destroying. One of my first cases was in 1996. It was a proposal by a Japanese-owned petrochemical company called Shin-Etsu to build what they were touting to be the world's largest polyvinyl chloride complex, and the name that they gave it was Shintech. And it was planned for the town of Convent, Louisiana, which is in St. James Parish. Folks outside of Louisiana may not know that we don't use the word "county," we use the word "parish." They mean the same thing in terms of a governing seat. And so fighting that proposal was something that I learned the importance of community organizing, the way in which my skill as a lawyer could be applied in a way that strengthened the voice of people to have a decision-making role in what would affect their lives and their futures and generations to come, and being able to use the law in a way that it may not have been designed, which is recognizing the right of Black people to live in a healthy environment.

The landscape in the corridor along the Mississippi River known as “Cancer Alley” is dominated by petrochemical and other plants. Many Black residents in fence line communities suffer from various respiratory and other ailments as a result of the pollution being emitted next door. Advocate and attorney Monique Harden says in light of the federal retreat from environmental justice residents have to use local land use regulations in their fight against polluters. (Photo: Jim Bowen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: So Monique, you live in Louisiana, not far from what is known as Cancer Alley. What is Cancer Alley, and why is it considered ground zero in the fight for environmental justice in the United States?

HARDEN: So where I live is in the city of New Orleans, which is in Cancer Alley. It's a section of the Mississippi River chemical corridor that begins just north of Baton Rouge and tracks the Mississippi River down to where it flows out into the Gulf of Mexico. Along this stretch of the river, on the land that abuts it, you'll find over 200 petrochemical industrial facilities. And in the midst of those towering smokestacks, are historic African American communities that were founded, some before the Civil War, many soon after the war, as safe havens for Black families to live and have a place that they could call home. This is with federal and state and local government decisions, our communities have become the targets of industrial development, beginning in the late 1930s and continuing to this day. So Cancer Alley is the name that communities that organize themselves around environmental justice have put a name to it because of the health damaging effects of this huge amounts of toxic pollution that's spewed from these industries.

BELTRAN: And there is a case involving the parish of St. James, which is being sued because an overwhelming number of the petrochemical facilities in St. James are located in majority Black districts. Tell us how that land use decision can be a friend or foe of environmental justice communities.

HARDEN: The case is an extremely important one that brings the attention to environmental justice arena. Before there's a permit issued, there has to be a land use approved for that industrial facility. If you don't have a sense of local governance that regards all communities fairly and with dignity, you can best believe that communities of color will be on the menu for toxic industrial development. And so what the Center for Constitutional Rights, Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, representing the community groups of Rise St. James and Inclusive Louisiana have done is looked at decades of decisions by the St. James Parish government that have approved and land use that may have been residential at one point, but now they've been designated as heavy industrial, where the neighbors are residents living in homes. And time and time again, those neighbors are Black residents, Black families. Holding the St. James Parish government to account on using constitutional protections is you know where that lawsuit is. So it's really looking at whether or not Black communities have the right to not be discriminated against in land use decisions.

Environmental advocate and attorney Monique Harden speaks about the long history of the environmental justice movement during the 2025 CEJM Conference at UMass Boston. Harden urges residents to use local land use and zoning regulations as a tool to prevent potentially harmful operations from operating in their communities. Harden worked as the head of Law and Public Policy and Community Engagement at the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice before her retirement. (Photo: CEJM)

BELTRAN: And there are, of course, a number of other lawsuits filed across Cancer Alley. What are some of those lawsuits? And what are they fighting against?

HARDEN: It's really what they're fighting for. And they're fighting for a healthy future, health and safety. And human dignity is central to that, and freedom from racial discrimination, because there's such a disparity in terms of who bears the severest burden of pollution in Louisiana's Cancer Alley. Like much of the United States and other parts of the world, it's people of color. It's African American, African descendant, folks, other people of color, Indigenous people, who are bearing these serious environmental burdens and climate impacts.

BELTRAN: That's a struggle. They've definitely taken this all the way to federal court. So that's a huge struggle.

HARDEN: It's a huge struggle, but it's an important one to have. Victory in that lawsuit would mean victory for a lot of communities where land use decisions are made without regard to their health and safety and their wellness. So the precedent setting effect of that can have national importance for everyone.

BELTRAN: Why is it important for Black Americans to understand and protect their history here in the United States, and how can that be a tool for healing?

HARDEN: I think it's important to understand history because it means that you have a sense of what your future could be, knowing the history around environmental justice, because I think it really does and is moving us toward, I think, with some urgency, climate solutions. Or if environmental justice was taken seriously 50 years ago, would we have this climate crisis today? The decisions that got us into this were decisions that did not value people, did not respect human dignity or human rights. And so that means our solutions have to be really wrapped around human rights and dignity and a sense of how special future generations are and that there's something we do today that affects them forever. Black history, I think, is extremely important, because it gives you a guidebook, if you will, around how to do things better today. Maybe it was a childhood asthma or maybe it could have been a climate disaster and a slow recovery that forced, or was a factor in moving away from a neighborhood or a place where that disaster happened. These are all signs of environmental injustice, and so it's about our survival to be able to, number one, be aware of this, and number two, organize to change it.

BELTRAN: Monique Harden is a longtime environmental justice advocate and attorney. Thanks for joining us.

HARDEN: Thank you.

BELTRAN: And Happy Black History Month.

HARDEN: Happy Black History Month. Thank you, Paloma.

Related links:

- Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences | “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial–Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure”

- CNN | “Hispanics and Blacks Create Less Air Pollution Than Whites, but Breathe More of It, Study Finds”

- New England Journal of Medicine | “An Association between Air Pollution and Mortality in Six U.S. Cities”

- Center for Constitutional Rights | “Lawsuit vs Formosa Plastic”

- Center for Constitutional Rights | “Sacred Ground - The Fight to Protect Burial Sites of Enslaved People”

[MUSIC: Mississippi John Hurt Shake That Thing (instrumental), a recording of john hurt playing "shake that thing" based on Papa Charlie Jackson 1925 version]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Residents in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley are looking to records of their enslaved ancestors to help fight the expanding petrochemical industry. Stay tuned. That’s next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mississippi John Hurt Shake That Thing (instrumental), a recording of john hurt playing "shake that thing" based on Papa Charlie Jackson 1925 version]

The Power of Black History

The Slavery Museum at the Whitney Plantation, the only former plantation site in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on slavery. (Photo: Cheburashka007, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I'm Paloma Beltran.

For more than 100 years before emancipation, enslaved people of African descent were forced to work the land along the Mississippi River near the city of New Orleans. They toiled to grow sugar cane in the rich soil and enriched white landowners with their free labor.

CURWOOD: Now centuries later, the legacy of slavery persists as the descendants of enslaved people live and work in one of the most polluted regions of the country, this 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as Cancer Alley. African Americans in the region disproportionately live with health problems associated with exposure to emissions from the roughly 200 petrochemical and industrial plants that give the region its infamous nickname. And industry in Cancer Alley is still expanding.

BELTRAN: The Taiwanese company, Formosa, is pushing for a new multi-billion-dollar petrochemical plant to be built on a piece of land known as the Buena Vista Plantation.But genealogists have uncovered evidence that enslaved people were buried on that land. And since several laws prohibit building on historical sites, community leaders are hoping that they can stop the expanding petrochemical industry by telling the stories of enslaved people in the region.

CURWOOD: In honor of Black History Month, we would like to share some of those stories as well. Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. An activist group against Louisiana’s expanding petrochemical industry. Lenora, Welcome to Living on Earth!

GOLBERT: Thank you very much, I’m very glad to be here.

CURWOOD: Please tell me how your genealogical research connects to resisting heavy industry?

A petrochemical plant owned by Formosa. (Photo: Formulanone, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

GOBERT: Well, it's really interesting. And the way I like to characterize it is, if you're familiar with some of the culture of Louisiana, there's something called a second line, which traditionally has been the line of people that have followed the casket and the musicians taking somebody to a burial site. And that's how I look at my work. There are people who have been fighting the fight against the petrochemical companies. And this includes the community organizations as well as lawyers and other environmental organizations working along with them. I am coming behind them to help document the claims that are being made about ancestors being buried on the plantations and therefore being threatened by the expansion of petrochemical companies. And people who are from the area have always said that there are grave sites there, there are people buried there. So this started sparking the interest of other community members and people working at the Bucket Brigade, to ask me to start looking into it and see what I could find. And yes, in fact, from the St. James courthouse, I went to the mortgage records to find out which enslaved people had been mortgaged by Benjamin Winchester, who owned the Buena Vista plantation. And a lot of people don't know that enslaved people were mortgaged to raise money to keep the plantations running. And there was an organization, or a financial organization called the Consolidated Association of Louisiana Planters that Benjamin Winchester mortgaged his enslaved people to. So I researched it and found out that their papers are held at the Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge. And I went up there, and they're just organized by month and by year in boxes. So I went there, and I had to start looking through documents from about 1820, up until about 1850, to see what transactions of Benjamin Winchester I could find. And in one of the papers, there was—he had a few papers where he had mortgaged people and he had them listed, but in this particular one, he had the men listed together, the women and the children. And there was nine-year-old Rachel, and next to her name was written the word "dead," - D-E-A-D. And that sent shivers up my spine, because obviously, Benjamin Winchester had intended to mortgage her, she was on the list with everybody else, but she died before he could mortgage her. So if she died, and she's from that plantation, logic and everything that we know historically about this institution says that she is buried on Buena Vista plantation, in the enslaved peoples' burial site. So that was how the story came about. This work that I did and this document that I found, starts setting the stage for other documents to be found in additional situations, to provide this as a tool to help stop these petrochemical companies from expanding further.

CURWOOD: So what does the records tell you about Rachel, the slave, aged nine, now dead, on this plantation?

GOBERT: Nothing, so far. Not many records were kept on enslaved people, as I'm sure you know. And a find like this is for me and for a lot of other genealogists extremely rare and very special, because it starts giving names and locations to people and what may have happened in their lives. But again, she was only nine years old. So I haven't revealed this yet outside of just talking to one or two people, but I have found the document where Benjamin Winchester purchased her and her mother and two brothers. So I know where she came from. I know who sold her, but I don't know anything about her life other than that, and that she died at nine years old.

Plastic nurdles created by ethane cracker plants like the ones in Cancer Alley. Plastic nurdles are the primary feedstock of plastic manufacturing. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, so, okay, where did she come from? Who sold her?

GOBERT: Well, there was an enslaver, or a slave trader, and his middle name was Fontaine, last name Rose and from Kentucky. So that's where he brought her from. I don't know if she was born there; likely, because she was so young. I don't know where her mother came from. Her mother's name was Eve, her mother was 20 years old when she was purchased by Winchester with her children. But their history earlier than that, I don't know yet. It takes a lot of digging, if you can find anything at all.

CURWOOD: Lenora, these days if we want to mortgage something to get a loan from a bank, we mortgage property and of course, slaves were property. But we typically mortgage land and the buildings on it. To what extent does this indicate that the, as far as the banking system was concerned, slaves were worth more than the land that they were being asked to work?

GOBERT: Absolutely. The enslaved people were the most valuable asset any of these people had, they were worth more than the land or the buildings by far. And that's what fueled the industry. And that's what, I think about the northern states that benefited from slavery also, we never really talk about that. But the banks up north also dealt with the enslaved people, mortgaging them or extracting their value, if you will, to provide financing for all kinds of building projects that people had at the time.

CURWOOD: So how do you feel that uncovering stories like Rachel's help to push back against the expansion of the petrochemical industry?

GOBERT: Well, you know, these are sacred sites, actually. But the fact that this area is considered so vital to the US economy, that this heavy industry must be sited there, means that they will do pretty much anything that they need to do to overlook the fact that there are human beings who are buried all along the river, there are thousands of these burial sites. But they do not want to acknowledge them, because of course, it prevents them from building there. So the sacred sites of the enslaved people count for nothing. And this is my opinion, but I believe that to be totally true.

Sugarcane fields in front of the Marathon Garyville refinery between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana. Enslaved African Americans once toiled to grow sugarcane on plantations, and today petrochemical plants are replacing agriculture in the region. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So the records that you found for Rachel indicate that she and her mother came from the Kentucky area. And there's a saying in the American English vernacular of being "sold down the river." How does that saying pertain in this case?

GOBERT: Well, technically, she wasn't sold down the river. But in terms of the concept, it's pretty much the same thing because, as you probably know, a lot of the enslaved people from the northern states, as well as the Mid-Atlantic states, were sold to the lower South. And a lot of those were to work on these sugar plantations. So conceptually, it was the same idea. Everybody's being moved south, because the labor needs are so high.

CURWOOD: What were the conditions on the sugar plantations for the slaves that worked there?

GOBERT: I'm not an expert on this, but it was brutal. And what's so interesting to me is when I first moved to New Orleans, I was really surprised how cold it can get here, how very cold it can get, in the 40s. So I started thinking about the enslaved people who were in these cabins, which of course, are not insulated, they may have this little fireplace in the middle where they can get a little bit of heat. But their clothes were thin, I guess they had one set of clothing, they may have had one thin blanket, can you imagine how it would have been for them, even when they weren't working? It had to be horrendous for them. And they were so resilient. Most of them, many of them, lived through these conditions, to produce all of these descendants. I think everybody should revere them. They should feel proud of them. They should say their names. And the only way we can get to say their names, is looking at these documents to find out who they are.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the money some more. How lucrative was the sugar business? How well were these white slave owners doing financially using these enslaved people?

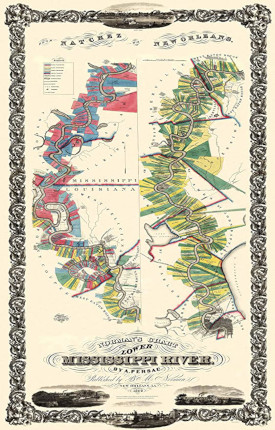

Pictured above is an 1858 Persac map of the Mississippi River in relation to plantations in Louisiana. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

GOBERT: Well, from what I've read, and I know it to be true, there were more millionaires along the river than anyplace else in the United States when these plantations were operating. It was so lucrative, this sugar industry, it was the fuel that ran the economy for the United States and the globe. I mean, England was so complicit in this. I'm hesitating right here, because it was so big. People don't think about how big this industry was globally, and that it all came from the labor of these enslaved people. But these people were extremely rich, extremely rich.

CURWOOD: The Mississippi River was home to many slave plantations, and of course, there are many descendants of the slaves still living there. And I believe it's on the scale of 150 petrochemical plants that are today spewing out contaminants associated with cancer, but many other diseases as well. What does that tell us about systemic racism in Louisiana? For that matter, what does it say about systemic racism in the United States of America?

GOBERT: That it's been there since the peculiar institution was invented, and it's never gone away. And because it's not right in our face the way it was in the 1700s, 1800s, it feels like things have gotten better. But you're right, institutionalized slavery is more insidious, it's there. It keeps people of color from reaching their full potential, from participating in the full economy of the United States. And for some reason, people don't want to hear this. They don't want to know this. And I believe that through the work that people like me are doing, genealogists, because we document individual family stories, and we document community stories, and we let people know what has happened and what is continuing to happen, and tie those things together for them -- plantation life is still going on to this day. It's in a different form, but it's still there.

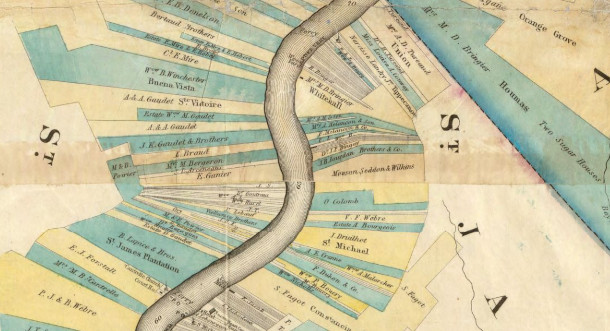

Pictured above is an 1858 map from Persac's Mississippi plantations map, that clearly shows the site of the Benjamin Winchester Buena Vista plantation at the top left. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: Are you suggesting that if you talk back against the chemical plant in your neighborhood, that you or your family is likely to lose their employment, their livelihood, there is no freedom for those folks?

GOBERT: I can't speak to that, specifically. The people who are in the communities and who are fighting against these plants, they would be able to tell you definitively whether or not that is true. But I do know just from talking to them that because people have jobs there, of course they're afraid to speak out. They don't want to lose their job. That's the only source of livelihood, everything else is being systematically pushed out. The communities are being pushed out, they're denuding the land of people. It's amazing. It's so systematic, and individuals fighting against huge corporations, huge money-making enterprises is very, very difficult. As a lot of activists and people who have been put upon in this country know, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: Now, what are some of the barriers that African Americans descended from slaves face in trying to trace their history?

GOBERT: Well, the main issue, I think, is the lack of documentation. A lot of families have oral histories, that when you dig into them and find documentation on the families, there are always nuggets of truth in their oral histories. They may be exaggerated, they may have changed over time. But there are nuggets of truth. And you can use those to help you find the documentation about the history of these families. But the main thing is that we've basically been written out of history, or haven't been written into history for the most part. So unless you can find the documentation, it's difficult, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: So to what extent is documenting and respecting the resting places of enslaved people a form of reparation?

GOBERT: I'm glad you asked that question, because I think we need to start really looking outside the box in terms of what reparations are. And one of the things that is important for me as a researcher is making documents of enslaved people, and even after they were free, making those documents much more readily available to be researched. My main topic, because I'm in Louisiana, is, well, there's more than one but a huge one for me is the Catholic Church. They have so many records, because they documented the lives of enslaved people, they have so many records that I feel should be made much more easily accessible. They should be using Catholic scholars to research some of this information and bring it out so that we all know and understand what's been going on with these enslaved people. The other thing is, too, that there are so many records in courthouses, these records that I talked about earlier, the mortgage documents that have enslaved people in them, they are somewhere on the shelves, all tattered and torn, falling apart, because they're not deemed to be important. And I'm sure there are other records in these courthouses that have information on enslaved people, but they're not easily accessible. So reparations -- that to me, is opening up the archives and every place that houses documents where there are documents pertinent to enslaved people's lives, and making them easily accessible.

Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: How can reconnecting with one's ancestors be empowering? What's the power you get from this?

GOBERT: I love that word "empowering" because I truly believe that a big part of the problem that we have in the United States is, with people who are of African ancestry, is a lack of self-esteem. And that lack of self-esteem for me, comes from them not knowing where they come from, what their people accomplished in this country. And once you started getting into those documents, you become amazed at what some of these people did after slavery and sometimes even before. So, if we knew where we came from and the contributions that our families made, not only that the resilience that they had to get through that slavery period, so that they are here today, I think they would really start having more self esteem, knowing who they are, feeling much better about themselves, and being able to move through this country in a more positive sense and more positive attitude and doing more things for themselves. That's my belief.

CURWOOD: Why is your work part of the quest to achieve environmental justice?

GOBERT: Environmental justice and racial justice and social justice, they're all intertwined. And the racial justice that we are trying to achieve, that we want to achieve, that we believe we will achieve, is to keep these communities on the land, where they have been for over 100 years. By these communities staying on this land and fighting the petrochemical industry, that is climate justice for them and everybody else because they will no longer be polluting the Mississippi River. They won't be polluting the land. They won't be polluting the air that has caused Cancer Alley to become Cancer Alley. So it's all connected.

CURWOOD: Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GOBERT: You are welcome and thank you for letting me have this conversation with you.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “This Nine-Year-Old Was Enslaved in the US. Her Story Could Help Stop a Chemical Plant”

- Learn more about the Louisiana Bucket Brigade.

- Don’t miss LOE’s previous interview on cancer alley with activist Sharon Lavigne

- Center for Constitutional Rights | "Graves of Enslaved People Found on Proposed Formosa Plastics Site"

[MUSIC: Eddie Cotton, “Here I Come” on Here I Come, DeChamp Records]

BELTRAN: Just ahead using neighborhood-level podcasting to fight environmental racism. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eddie Cotton, “Here I Come” on Here I Come, DeChamp Records]

The Quest for Env. Justice in Shiloh Alabama

Heavy rainfall in Shiloh, Alabama, is usually followed by flooding as runoff rushes down from the widened and elevated Highway 84. Residents say flooding has eroded their yards, cracked their foundations and caused septic tanks to overflow into their yards. (Photo: Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

For Black History Month we bring you a cautionary tale brought to us by the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media or CEJM. CEJM helps people of color learn how to tell their own stories in the face of environmental injustice and the climate emergency. It is a collaboration between Living on Earth and the UMass Boston School for the Environment with support from the Waverley Street Foundation. Nana Mohammed and Andrew Skerrit trained Shiloh, Alabama storyteller Melissa Williams to interview community members about their efforts and concerns as they seek justice from the State of Alabama after highway construction flooded their homes. With the help from the father of environmental justice Dr. Robert Bullard, Shiloh residents looked to the highest levels of government to be made whole.

WILLIAMS: Here in Shiloh, our community has been affected by flood damage due to the expansion of highway 84 by the Alabama Department of Transportation six years ago, and we face choices of what is to be done. My name is Melissa Williams, and I'm talking to people here in Shiloh so we can hear each other, understanding we are not alone with these challenges. Many other communities of color are facing issues of what some call environmental justice.

[SFX highway]

[Music: TAOUDELLA AZALAI, CHOARCOAL LINE]

WILLIAMS M: When I was 16, coming back from the church, one Sunday afternoon, we found our home flooded. Water was running through our living room, bedroom and kitchen.

[SFX highway]

WILLIAMS M: The damage was caused by the rainwater runoff from the widening of highway 84 an expressway that passes through the heart of our community, Shiloh, which is located in our small town of Elba, Alabama. At the time, it was very confusing. Our friends and neighbors were also affected. Yards kept flooding. Septic tanks overflowed. Our house foundation began to show cracks. Water moccasins made it dangerous to go outside after a heavy rain. At 22, I began to reflect on what had happened that day and the troubles that followed in the years afterwards. My name is Melissa Williams, and I'm here today with my father, Timothy Williams, seated in our living room to start a conversation about the struggles of the last six years.

Shiloh resident Rev. Timothy Williams (right) shows pictures of the damage caused by flooding from runoff on Highway 84. Dr. Bob Bullard (left), who grew up in nearby Elba, Alabama, looks on. Bullard, a pioneer in the environmental justice movement, has worked with Shiloh residents in search of justice. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

[Music]

WILLIAMS M: Shiloh is a historical Black community where land has been passed down from generation to generation. I want to talk about this unique story that has to do with environmental injustice, because I'm sure there are others that are going through the same thing that Shiloh is going through. So me talking about what we're going through, I'm sure this could help someone today, tomorrow, in the future. To better understand the history of this historical community, I'm going to turn it to my father to speak about his upbringing and how he was raised here in Shiloh. Okay, Dad, can you tell me about your upbringing and the history behind Shiloh?

WILLIAMS T: When I was about probably 14 or 15, I would come to the Shiloh community. My grandparents were here. This is where my mom, she was raised, here in the Shiloh. Everybody in the Shiloh community, here is family. Land has been passed down in our family from generation to generation. It has been in our family since Reconstruction. We were all taught to keep the property in, you know, in the family, you know, pass it down from one generation to the next. So I was the third generation, and so you're the fourth generation, where the land will be passed down to you. The Shiloh community is rich in generational wealth. Back in the days, they did a lot of things here, this property was farmland. Back in 1960s homes were beginning to be built. In the 1970s here, the land here was flat. We never had any flooding. We didn't have to deal with forced storm waters onto the community. It was just a normal life. And then years later, in 2004 I was inherited this house, we began to occupy the place. And so it's been 20 years.

Shiloh Storyteller Melissa Williams listens to speakers during the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media (CEJM) Conference at UMass Boston in September 2025. Williams has interviewed about half a dozen of her Shiloh neighbors as part of the Shiloh CEJM project. (Photo: CEJM)

WILLIAMS M: For me, I can share my little memories of me living here, being raised here, about how we would just be able to go outside. Like you said, we didn't have any problems that we're having now, just dealing with the water, frogs, snakes, all that stuff. We didn't have to experience any of those things. We will be able to go outside, ride bicycles, play in the mud, make like, you know, little dirt pies, all of that stuff.

[SFX kids playing]

WILLIAMS M: Yeah, we just lived normal lives. I mean, what little kids would do outside.

Could you tell me about how this affected you, with the Highway coming through here?

WILLIAMS T: Going from a normal situation to now, where it's horrific, where they have forced the waters on to us. It was devastating. I mean, it changed a lot of things for us. We started experiencing so much things like home sinking and flooding in the yards and where we couldn't even get in, or we couldn't even get out. We kept complaining about it to the state and everything. And this thing has became horrific because they didn't want to do anything. And so here it is. Here comes the mud, even during Reconstruction, can't even leave out to drive.

WILLIAMS M: I know I can remember coming from church on Sundays, and this is when it first started flooding. Sunday afternoon at the church, came home, it had rained, and literally, the car porch was filled with water. The basement was filled with water. We had to go take towels to try to soak up all the water.

The Shiloh neighborhood sits along the east bound lane of Highway 84. Since the roadway was widened from two lanes to four and raised, residents say they feel as if they live in a bowl that fills up with rainwater runoff following heavy downpours. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

[SFX water sloshing]

WILLIAMS M: I mean, that didn't really too much help, but we did everything that we could to get the water. And it just kept happening over and over again every time that it would rain. It was crazy. After the first flooding situation, and after we had to, you know, get, use the towels to clean the water, what did you do for us to take action?

WILLIAMS T: I contacted the state of Alabama, told them what was going on, but then they turned a deaf ear to us. Didn't want to hear it. And so after that, you know, we had some, you know, backlash again. And then—

WILLIAMS M: What do you mean by backlash?

WILLIAMS T: The backlash came from the state of Alabama, you know, because now here is we got an attorney involved. We're trying to alleviate the situation, because they never listen to us. Every time we complain, even in notes, we kept complaining and talking about how they forced the water, even during construction, they flooded us out, and they kept on, the water kept coming, and it was like though they weren't hearing us.

WILLIAMS M: How would you describe the frustration when you would ask for help, and these people, they wouldn't help you, especially with the lawyer, thinking that you're going to get help with your lawyer, and there's no help.

[MUSIC: TAOUDELLA, AZALAI, BLUEDOTSESSIONS]

WILLIAM T: It was sad, because here it is. You thinking, people will have your best interest. Because first lawyer I talked with, he says, we cannot help you, because there's a conflict of interest, because they represent the state of Alabama, we were misled. It was bigger than us, and they want our property, and they want us out of here, and they don't want us to talk. So it was a frustrating situation.

[MUSIC: TAOUDELLA, AZALAI, BLUEDOTSESSIONS]

WILLIAMS M: Well, how did your life or your perspective changed when you were able to get in contact with Dr. Bullard?

The section of Shiloh, Alabama affected by flooding from Highway 84. Most of the local residents can trace their family’s connection to the area to the Reconstruction era and have vowed to remain, despite flooding problems caused by the elevation of four-lane highway. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

WILLIAMS T: It changed dramatically, because it was five years and four months we were dealing with this situation. And so here it is, when FHWA came, they saw the situation, but then they told people, Hey, y'all got to stay quiet. You can't get other folks involved. You can't go back on the media. I was told Dr. Bullard the father of environmental justice. And I asked a question to a lot of people that was telling us, you need to get in touch with your cousin. You need to call Dr. Bullard. That man is all over the world. He's a father of environmental justice. How is that gonna be? I'll never forget one day I left from the restaurant. It was on my birthday, on June the first, and I'll never forget this. On my way back from up Alabama, the Lord spoke to me and said, go by Dr. Bullard's brother's house. And so I obey God. And I went by there, and I knocked on the door. Then here come Leon, his brother. He said, What you doing here? You supposed to be at that restaurant, right? I said, Yeah. I said, but I had to stop by here. I got to get in touch with Dr. Bullard. And I said, let's call your brother. Do all of that. He didn't pick up the phone. I said, I tell you what. Let's text this video to him and let him see this video. Between one and two o'clock that afternoon, we get some phone call from Dr Bullard, and the first thing he says is, this is horrific. And he says, I tell you what, so I need you to gather the people together. And it was less than 24 hours. We're in a zoom call with Dr. Bullard, and he assured us. He said, if I cannot fight for my community and for my city and for my family, I don't need the name father of environmental justice, he said because I'm fighting everywhere else and I can't come back home? He says, I want to assure y'all that I'm gonna be with you and I'm gonna help you, and we're gonna get victory on this situation. And that's when he came and it changed the whole dynamic of everything.

[MUSIC: STUFFLED MONSTER, BLUEDOT]

WILLIAMS M: I can remember when Dr. Bullard told us that we're going to Washington, DC, and he said that we're going to go to US DLT to share our stories about this situation that's going on in Shiloh. What was your experience when you were in the room?

The CEJM Shiloh team wraps up a weekend of interviews in summer 2024. From left to right: Andrew Skerritt (CEJM storyteller), Melissa Williams, Nana Mohammed (CEJM field producer), and Melissa’s parents, Monica and Timothy Williams. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

WILLIAMS T: Never been to DC, sitting at tables that we never would have known of. And the first thing was like people saying, we don't want no false hope and everything.

[music]

WILLIAMS T: 2018 I was fired from my job at the school, and then didn't have no work. And so that's when Destiny came about, and that first year is when the construction ended, even though we were fighting that I took my kids and I began to put them into, allowed them to work with the cleaning business, to alleviate a lot of the frustration, a lot of the things that we were going because if we dwelled on what we were going through, people would lose their mind, go crazy, the kids would be so frustrated they couldn't even function.

WILLIAMS M: I can say that before Dr Bullard had came into helping us, it was a very frustrating situation to see that we couldn't get through no doors, false hope. It was just a lot of, dang what can I help do? Can I do this, like…

WILLIAMS T: I kept grinding, I kept moving, I kept contacting people. Doors kept being closed. It became frustrating, but we didn't give up.

WILLIAMS M: [pauses] Sorry, my emotion.

WILLIAMS T: Melissa, what made you so emotional now, you know, talking about the five and a half years?

WILLIAMS M: I feel like it's just the fact that at the time when this was going on I was 16. So in your head, as a 16-year-old, you're like, what, the financial problems and all of that? You're trying to figure out, what can I do to help at the age of 16? So it's triggering for me, and it's—emotional. It's something not really too much like talking about. It's just the fact that there's a lot that's going on, and you're 16, so at the age of 16, you don't, you don't, your average 16-year-old is not thinking about ways to help their parents, like…

WILLIAMS T: When I got the call from Secretary Pete Buttigieg, it was a week before, they were on the plane headed to Maryland, and then Secretary Pete Buttigieg and Christopher Cole, Assistant Secretary, called and said, Pastor, we want to let you know that I would be in Shiloh next Wednesday.

In 2024, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg visited Shiloh along with Highway Administration officials to see the Shiloh damage for himself. As a result of the visit, the Alabama Department of Transportation and federal officials reached an agreement to address the drainage issues. ALDOT announced that the work will be completed this year. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

WILLIAMS M: I can remember my dad coming to the restaurant telling us that Pete Buttigieg had just called him. He just got off the phone with Pete Buttigieg, and he was saying that he was going to come here to Shiloh and walk the grounds with us to listen to what other residents have to say about their homes, their experience. It was an amazing feeling. It made you feel like, okay, they were listening. They heard everything that we were saying. They actually do care, because we received false hope previous, before. So it was a, it was a good feeling. What it was like for you getting the call from Pete Buttigieg to him telling you that he was coming here to Shiloh?

WILLIAMS T: It was a prayer answered, because now you see that that trip DC, it wasn't in vain. It triggered some things in there. I could remember everybody around the table when we was telling our story. They were crying and even talking with Secretary Pete Buttigieg, he even assured me. He says, I'm not going off what people are saying. You know, I want to come and hear this for myself and see it for myself. People think this is fabricated.

BUTTIGIEG: I don't claim to have a magic wand on me, but I got a lot of tools because, as both Reverend and Dr. Bullard said, one thing I'm sure of is that nobody in this community is responsible for what you all are going through, and nobody should have to live with what you all are going through right now.

[music]

WILLIAMS T: You know, going to DC was not in vain. Somebody heard us, you know I'm saying, and that means a lot. It changed the whole dynamic.

WILLIAMS M: Where would you say you find strength?

WILLIAM T: This is nothing to do with Williams, you know I'm saying, that's where I find the strength. Because after losing everything you know, sorry, man, you know you got to have strength of the Lord, because everything has been taken. You know, my business, my cleaning business, boycott at my restaurant, is nobody but God. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. And that's the key, and so you got to have a servant mentality if you're going to do what we're doing in the Shiloh community.

The Rev. Timothy Williams, a leader in the Shiloh community, conducts a media tour in 2024 to show the damage caused by flooding from Highway 84. Williams said his activism has hurt his family financially with lost contracts and a boycott of the family’s restaurant. (Photo: Andrew J. Skerritt)

WILLIAMS M: What is something that other communities that are going through environmental injustice learn from this situation in Shiloh?

WILLIAMS T: And a lot of people are afraid of what what backlash they're going to get, and what's going to happen to them if they speak up. If it's wrong, speak up and speak out. A lot of communities can learn from us. From the Shiloh community is because we're a community that refused to shut up. We're community that refused to sit back and just let them take our property, because that's what they want. They want your property. They want to destroy your livelihood.

WILLIAMS M: I just want to say thank you to my dad for being a role model in my life.

WILLIAMS T: Well, thank you too, Melissa, you know, thank you all for hanging in there, even when you lost. You still fighting, and that's what it's about. And I believe that means more you know, you.

BELTRAN: The Biden administration did not deliver the promises made to the Shiloh community before the Trump White House took over. On January 8 the Alabama Department of Transportation presented plans to improve drainage along highway 84 in the Shiloh Community, but with no mention of compensation for the damages residents have suffered.

Related links:

- Alabama Department of Transportation (ALDOT) | “Drainage Improvements, Highway 84, Shiloh (Coffee County)”

- Learn more about the Center for Climate and Environmental Justice Media (CEJM)

- Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice | “The Clock is Ticking: ALDOT Needs to Hold Public Meetings On Drainage Improvement Project in Shiloh Community”

- ABC News | “A Year After Alabama Signed a Civil Rights Agreement to Limit Flooding, Residents Still Fear Every Rainfall”

- Inside Climate News | “Black Alabamians Sue State Department of Transportation Over Repeated Flooding”

[MUSIC: Alain Apaloo, “Lonely Soul” on Naked, Heartcore Records]

CURWOOD: Save the date for our next Living on Earth Book Club event on Thursday, February 26th! Acclaimed nature writer and New York Times bestselling author Terry Tempest Williams will join us on Zoom to discuss her new book The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary, and you can be part of the conversation. So, join us online Thursday, February 26th at 6:30 pm Eastern. Check out LOE dot org slash events to learn more and register for this free event!

[MUSIC: Buddy Miles, “Texas” on Best Of Buddy Miles, The Island Def Jam Music Group]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Sophie Bokor, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Julia Vaz, El Wilson, and Hedy Yang.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram, Threads and BlueSky @livingonearth radio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth