November 28, 2025

Air Date: November 28, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Deadly Toll of Wildfire Smoke

View the page for this story

Wildfire smoke is fouling air quality across the US with increasing regularity, and it carries a heavy toll. A September 2025 study published in the journal Nature found that every year around 40,000 Americans are dying from wildfire smoke, with more on the way as the planet warms. Senior author Dr. Marshall Burke, a professor in the Doerr School of Sustainability at Stanford University, joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how air filters, face masks and low-intensity prescribed burning can help protect the public from this growing threat. (12:57)

Underpaid Incarcerated Firefighters Get a Big Raise

View the page for this story

Around a third of the firefighters who battle wildfires in California are incarcerated, and until recently they were paid just $5 to $10 a day. Under a state law enacted in October 2025, incarcerated firefighters are now paid at least $7.25 per hour while actively fighting fires. Formerly incarcerated firefighter and current fire apparatus engineer for the state of California, Eddie Herrera, Jr., returns to Living on Earth to speak with Host Aynsley O’Neill about how this pay raise can help transform lives. (09:21)

Wildfire Trauma and Recovery

View the page for this story

Wildfires can take a huge mental toll and people who live in wildfire-impacted communities may experience post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. Host Jenni Doering tells Host Aynsley O’Neill about her frightening childhood experience of the 2003 Cedar Fire in San Diego and they discuss emotional resilience strategies shared by Jyoti Mishra, a UCSD professor of psychiatry who co-directs the University of California Climate Change and Mental Health Council. (05:43)

Stream Life is Thriving 5 Years After Oregon Fires

/ Jes BurnsView the page for this story

In 2020 Oregon faced its most destructive wildfire disaster, when more than a million acres burned in the “Labor Day” fires. The sheer size and severity of those fires gave scientists a unique chance to learn what happens after a massive burn. Jes Burns of OPB reports on the surprising resilience of fish and amphibians five years after the fires. (04:54)

"Good Fire": How Cultural Burning Heals Land and People

View the page for this story

Around the world, Indigenous people have been using fire on the landscape for thousands of years. One such practice comes from the Métis tradition in Western Canada. Cree-Métis scientist Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is a senior fire advisor with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share how this low-intensity “good fire” helps rekindle cultural traditions and cultivate healthier ecosystems. (13:59)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251128 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Marshall Burke, Amy Cardinal Christianson, Eddie Herrera, Jr., Jyoti Mishra

REPORTERS: Jes Burns

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Today on the show, wildfire smoke takes a huge toll on society.

BURKE: And so when you count up total mortality across the US we get a number of about 40,000 excess deaths per year from wildfire smoke over the last decade. Forty thousand, that’s roughly on par with the number of people who die in car accidents in the US every year.

DOERING: Also, wildfire resilience and how some Indigenous people are cultivating “good fire.”

CHRISTIANSON: I really think the beauty of it is just getting people out on the land together and really being proud of their culture. There's so many divisive things in the world, but when you really get people out on the land and learning and being with one another, it really helps, and for, you know, mental health, physical health and other things of people who participate.

DOERING: That’s this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Deadly Toll of Wildfire Smoke

The Silver King wildfire in Utah burns near Beaver Canyon, Utah in July 2024. A new study in Nature finds that there have been about 40,000 excess deaths from wildfire smoke every year in the US over the last decade. (Photo: Derrellwilliams, Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Our show today focuses on fire, including the growing threats our society faces from extreme wildfire as the planet warms. But fire is a creative as well as destructive force, so we’ll spend time later in the show discussing the roles of fire in ecology and culture, as well as how we can help each other heal and recover from the collective trauma of living through these megafires.

DOERING: Yeah, and it really is a collective trauma for many here in the U.S. I mean, whether or not you’ve found yourself in the direct path of a wildfire, chances are you have been in the widening path of wildfire smoke and experienced the scratchy throat, coughing, and burning eyes that exposure can bring.

O’NEILL: Yeah, you know Jenni, I certainly remember a lot of extra throat clearing when we’ve recorded this show during some of those really smoky days!

DOERING: Yes, me too. Wildfire smoke has become extremely noticeable anecdotally but also in the scientific data. And a September 2025 study published in Nature quantifies just how deadly that smoke can be in a warming world. The researchers found that around 40,000 Americans are dying from wildfire smoke every year, with more on the way as the planet warms. Here to talk to us about the study is senior author Dr. Marshall Burke, a professor in the Doerr School of Sustainability at Stanford University. Hi Marshall, and welcome to the show!

BURKE: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: So we're talking to you about your recent research regarding the link between wildfire smoke and mortality. Talk to me about what kinds of questions you were asking and what you found about how smoke is killing us.

BURKE: People have a sense that breathing in smoke is bad for them. We set out to understand, okay, how bad is it actually? And we looked at really, one of the most severe outcomes, so thinking about excess mortality, and wanted to understand how exposure to wildfire smoke in the days or weeks or even years past an exposure, how that affected excess mortality, the likelihood that you would die. And unfortunately, we see pretty large effects. We see that in the year of smoke exposure, mortality goes up substantially, and those effects last for multiple years. So the largest impacts, in terms of people affected and overall impacts, they're larger in the US West, because exposures tend to be higher. But again, in the last few years, we've just seen a lot more exposure elsewhere in the country, and so people on the East Coast and the Midwest, increasingly in the US South are exposed to wildfire smoke. And so when you count up total mortality across the US, we get a number of about 40,000 excess deaths per year from wildfire smoke over the last decade. Forty thousand, that's roughly on par with the number of people who die in car accidents in the US every year.

A DIY air filter called a “Corsi-Rosenthal Box” made from four MERV 13 filters taped together to form a cube, with a box fan on top that draws air through the filters. Our guest, Dr. Marshall Burke, suggests making your own air filter if buying one is cost prohibitive. (Photo: Festucarubra, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: And then you also projected out these numbers into the future because, you know, we know that these wildfire risks are probably not going to decrease in the coming decades. They may, in fact, be getting worse as climate change intensifies. So what did you find there?

BURKE: That's right. We wanted to understand whether this was the new normal and how it might change in the future. And here, we really built on decades of work showing why we were seeing an increase in wildfire activity and smoke overall. And really there, there are two main causes. One is a century of fire suppression, where we've put out fires instead of let them burn in our forests. Many forests had evolved with fire. We sort of interrupted that about a century ago, and what that led to was a loading of fuels in these forests. So I go hiking in the Sierra Nevada a lot. You go into many of these forests, and there's just an incredible amount of dead wood and fuel on the ground in these forests. You add on top of that a warming climate. These fuels dry out. They become more flammable. And so, when you do get a spark, the fires grow much more quickly. They're much more extreme, and they emit a lot more smoke. So we know from climate models that the climate will continue to warm in the future. And so we were able to model out, okay, what's going to happen over the next 20, 30, years in terms of expected wildfire activity and expected smoke output. And sure enough, as the climate continues to warm, under a business-as-usual scenario where we sort of behave as we have over the last few decades, in the future, we find a pretty substantial increase in smoke exposure and resulting health burden. So we estimate that, you know, again, we're at 40,000 deaths annually now. This could rise to 70,000 deaths by 2050, so like a 70% increase in the health burden just over the next two to three decades.

Our guest, Dr. Burke suggests wearing an N95 mask if you have to go outside on a day when there is bad air quality. (Photo: Debora Cartagena, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

DOERING: Wow. I imagine that's not just from population increases either.

BURKE: No, it's not just from population increases, although that does play a role. Another important role is the aging of the population. So we certainly find that elderly groups are more susceptible and more vulnerable to wildfire smoke, and so as our population ages, that certainly makes us as a society, more vulnerable. So that's part of the story. The main part of the story, though, is just the overall warming climate, the resulting increase in fire activity and smoke exposure that we get. So what we can do is we can take those total deaths that we spoke of, so 70,000 deaths by 2050, we can do what economists are happy doing, what other people understandably view as sort of insane. But we can convert these deaths to dollars using the official US government number of how much a statistical life is worth, which is about $10 million. And if you do that multiplication, you get many hundreds of billions of dollars of damage every year from wildfire smoke alone. Our estimate is that that is the largest single impact of climate change in the US.

DOERING: Wow. All right, I was already blown away by your research. And how about if we get our act together on climate and really reduce our emissions?

BURKE: So unfortunately, by mid-century, we find that even pretty aggressive climate mitigation, so if we really get our act together and reduce emissions, that will have a benefit. But the benefits, at least by 2050, in the next few decades, are pretty small. And the reason for that is just that climate change is a very slow ship to turn. And so if we reduce our emissions today, that can have massive benefits, but most of those benefits are later on in the century. So by 2050, there are certainly benefits, but they're just not as large as what you get by 2070 or 2080 or end of the century. We find sort of a small difference, so maybe 60,000 or low 60,000 deaths under a very aggressive mitigation scenario, versus about 70,000 under a business as usual. So certainly a benefit, but it doesn't eliminate the problem.

Fire consumes low-level brush during the 2025 NASA FireSense research campaign, centered around prescribed burn operations at Fort Stewart-Hunter Army Airfield in Georgia. Prescribed burns can potentially reduce excess fuel in forests and prevent extreme wildfires. (Photo: NASA/Milan Loiacono, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

DOERING: Wow. So I guess we all better be a little more prepared for what's coming and what's already here, to be honest. So as wildfire smoke poses this increasing public health threat what are individuals doing to protect themselves?

BURKE: I think there's two questions: What are individuals doing to protect themselves, and what should they be doing to protect themselves? So this is something our group has looked at, is to try to understand what are people doing now to protect themselves? One way we've studied this is to use really nice citizen science data, basically data that are available to us based on individual citizens, just out in the population, collecting data, either on purpose or inadvertently. So specifically, we use these purple air monitors that many people have put in their homes that serve data publicly that we can then as scientists analyze. What we can do is look at people's indoor air concentrations on wildfire smoke days, so on days in which the smoke outside is really bad, to understand, is it sufficient to stay inside and close your windows and doors on a really bad wildfire smoke day? This tends to be the main public guidance. The air is bad outside, stay inside, close your windows and doors. So we can look at people's monitors and say, "Okay, how well are they doing?" These are indoor monitors. What are the pollution concentrations? And these are people with monitors, right? So these are people who should have very good information on what their exposure is. Basically we see two groups. We see one group that seems to be doing something well, their indoor air quality looks quite good on a smoky day. We see it basically the other half of the group where the opposite is true. Their indoor air quality can be almost as bad as the outdoor air quality on a really bad smoke day. And these are in pretty wealthy Bay Area neighborhoods, like these are my neighbors down the street. And so the question is, what's going on? And almost surely, what's happening is they have windows and doors that are open, and so wildfire smoke is infiltrating into these environments. And these are people with monitors. They're the ones who should be best informed about this exposure, right? So that tells us, at least right now, we are not super well-prepared for this.

The aftermath of the January 2025 fires in Altadena, CA. When extreme wildfires burn materials like cars, bicycles, and household materials, the resulting smoke could contain potentially toxic materials. (Photo: Russ Allison Loar, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So what really should people be doing? I mean, obviously, closing windows, trying to keep doors closed as much as possible when there's a lot of smoke around. But I mean, is there anything else that we should be doing, especially when we do have to go outside?

BURKE: Yeah, there's a number of things we can do. And the science is still catching up in terms of the overall health benefits of these strategies, but there's some things that look pretty promising. Number one, closing your windows and doors is certainly the place to start, but the key thing is having an ability to filter your air indoors. So these can be portable air filters. They cost, typically, a few hundred dollars. You can build them yourself with fans and a MERV filter for about $50. And these work really well, if they're sized correctly, work really well to keep air quality pretty clean indoors, even if it's bad outdoors. And so that is our main strategy, if you're inside, for improving air. So what we need to make sure, though, is that, number one, people have this technology and know when to use it. And number two, you know, everyone can afford it. Many of us can go out and spend a few hundred dollars on an air filter. Others can't. And so, we need to make sure, using public policy that everyone has access to this technology. That's number one. Number two, many people do have to work outside. Many of us have to go outside in various parts of our lives, and so we need to protect ourselves as best we can when we're outside as well. Wearing a good-fitting N95 mask can help a lot. And so we have those masks. They might be buried in a drawer now, but dig them out on a wildfire day, put them on as best you can. You can't wear them always. If you're doing heavy activity, they're obviously hard to wear. Our goal is probably not to eliminate exposure, it's to reduce exposure as much as we can.

Dr. Marshall Burke is a senior author on the study and a professor in the Doerr School of Sustainability at Stanford University. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Marshall Burke)

DOERING: So if we do everything in our power to address the climate crisis, the conditions that lead to extreme wildfires will still be with us for a long time. So it makes sense. We need to thin these fuels. Prescribed fire can be one way to do that. That, of course, is creating smoke. But to what extent is there a difference between that smoke and the really intense burning that we're seeing with some of these out-of-control wildfires?

BURKE: Yeah, that's a great question. There's two main components of the difference. One is, is the smoke itself somehow different in terms of its toxicity? So when we think about wildfire smoke, we're really thinking about a really broad and complicated mix of pollutants and chemicals and toxins, potentially. And unfortunately, they are toxic chemicals you get when you get increasing urban incursion of wildfires, right? When wildfires burn into cities and towns, and they burn up our houses, everything that's under our sink or in our garage. They burn up cars or bicycles. And so when you inhale that wildfire smoke, you're inhaling part of a car, right? And what does that do to you? It certainly can't be good. And again, this is a place where science is, I think, trying to catch up in terms of understanding the toxicity. To me, that's not the most important difference. The most important difference is just the overall quantity of the smoke that you get. And the whole goal with prescribed fire is to put low severity fire on the ground that really doesn't generate that much smoke in the hopes of reducing really extreme wildfires that we know generate a lot of smoke. Our estimate suggests that the reduction in smoke you get is three to five times higher than the initial smoke that you emit from prescribed burning. So to us, that looks pretty good from a cost benefit perspective. Again, it's a tradeoff, though you are going to get some smoke initially, and people need to be aware of that. And they need to be, I think, educated about the tradeoffs. This is indeed a tradeoff.

DOERING: Dr. Marshall Burke is senior author on the study and a professor in the Doerr School of Sustainability at Stanford University. Thank you so much, Dr. Burke.

BURKE: Great to talk to you. Thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: Dr. Burke and his team have put together a tool where you can learn more about smoke pollution trends and health impacts, and we’ll post the link at the Living on Earth website, loe.org. We’ll also link to a guide to that DIY $50 air filter.

And if your home has forced air, don’t forget to check those air filters, since they usually need to be replaced every 3 months or more often when it’s smoky out!

Related links:

- Read Dr. Burke’s study in the journal Nature

- Learn more about the air quality near you with a tool built by Dr. Burke and his team

- Learn how to build a DIY air filter

[MUSIC: Watchhouse, “Wildfire” on Blindfaller, Yep Roc Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, wildfires take a huge toll on our mental health too. We’ll cover some strategies for resilience in the wake of traumatic wildfires. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: River Foxcroft, “Thoroughfares and Turnpikes” on Dayspring Dew, Epidemic Sound]

Underpaid Incarcerated Firefighters Get a Big Raise

Our guest, Eddie Herrera Jr. at the Green Fire in San Luis Obispo County in 2024. Herrera worked his way up from being an incarcerated firefighter to being a fire apparatus engineer for the state of California. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

When wildfires like the 2025 Palisades and Eaton fires rage across California, around 30% of the firefighters battling the blazes are incarcerated. This California penitentiary program trains inmates in the same skillset as professional firefighters and puts them on track to be hired upon release. Until recently, these incarcerated firefighters were paid an extremely low wage - typically between $5 and $10 a day. Now, that pay gap is starting to close. In October 2025, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill requiring incarcerated firefighters to be paid $7.25 per hour while actively fighting fires. Here to talk to us about the impact of this law is formerly incarcerated firefighter and current fire apparatus engineer for the state of California, Eddie Herrera, Jr. Hi Eddie, and welcome back to the show!

HERRERA: Thank you. Thank you. I appreciate you guys having me here again. It's awesome to be back and under a different title now, but it's awesome. Thank you for having me.

O'NEILL: Congratulations on the promotion, yes. You've shared your story on the show before, but for those who might not remember, please tell us a little bit about your experience during your time as an incarcerated firefighter.

HERRERA: Yeah, so I served 18 years in the State of California, and then those last two years, I operated as a institutional municipal firefighter at an institution firehouse for the state of California. And so I fought wildland fires, vegetation fires, ran medical calls, structure fires, but yeah, that was my, my job. I was an incarcerated institutional firefighter.

O'NEILL: During that time, how much were you paid for your service?

HERRERA: So I made $56 a month. That was the max I could get paid for that position, being at the firehouse, which came out to a roughly $1.80 an hour. And you get deductions for restitution and different stuff like that. It came out to like $41 a month.

O'NEILL: And for those who might not be aware, what is restitution?

HERRERA: So restitution is what the courts apply to your case. In regards to restitution for whether it could be for victim, where it could be for court fees, it could be anything that has to do with the legal system. So if you have a lot of restitution, it can add up into the thousands, but fortunately for me, in my case, it was not that much. It was $200, so I paid that off. So yeah, it's just a court-imposed fee in regards to whether it's restitution for your victim's property or court fees.

On March 11, 2025, Herrera advocated for the passing of bill AB 247 in the California State Assembly. The bill vastly increases the pay of incarcerated firefighters. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

O'NEILL: So in terms of the pay, what would be the difference between an incarcerated firefighter and a non-incarcerated firefighter?

HERRERA: In comparison, it's a lot of a difference. So average, your Fire Fighter 1 for the state of California can make up to $62,000, and that would be your base pay. Definitely can increase if you are working overtime and you're out there fighting active fires. So if you do the numbers, I mean, let's just say $21 an hour, there's a big difference in regards to $1.80 an hour, or $1 an hour fighting active fires, as opposed to making that amount. So in comparison, it is a huge gap.

O'NEILL: So as of October 2025, California Governor Gavin Newsom has now signed a bill that requires incarcerated firefighters in the state of California to be paid $7.25 an hour while assigned to an active fire. On a practical level, how will this change the lives of incarcerated firefighters?

HERRERA: Wow, great question. On a practical level, it is big, and let me explain to you how what I mean. Not only is it good as far as public safety and the reason why it goes back to restitution. This is part of being able to give back for whatever crime you committed, whatever offense, you're able to now the state and the victims are able to get back, right, restitution, because the more you make, the more it goes towards your victims. As well as, public safety wise is, the more money you make, the more you're able to transition when you do come home, because you're able to start having money to get set up, build a foundation. As opposed to before, it was very challenging, because you get out, you get your gate money, your $200 upon release, and then you're going to be rely heavily on the state services or family members, right? So in this case, it's very different in the sense that you can realistically be paroling with up to $20,000 in a good fire season, right? So if you manage your money wisely, have that money saved up, you can have money to get yourself food, clothing, whatever it is you need to do to transition back into society. So if you think about it in the sense of public safety, it's less of a burden on the state and society itself to be able to have to say, hey, we're just going to have a revolving door in recidivism, right?

O’NEILL: Mm hm.

HERERRA: So it's huge, in that sense. So now with this pay, it's going to allow them to, one, pay restitution, two establish a foundation upon coming home, and three, actually start helping out family members and loved ones while they're in there. Because most individuals, when they're in there, it's a huge burden on family and loved ones, because they're the ones that are supporting their loved ones that are still incarcerated. So now, in this case, it kind of flips that, right? They no longer have to ask for help. Instead, they're the ones being able to say, "Hey, I want to take care of my daughter, take care of my son, take care of my mom." And they can actually start sending money home, if they like. So yes, it's huge.

Herrera says that one of the key benefits of raising the wage of incarcerated firefighters is that it enables them to support their families while incarcerated. Pictured here is Herrera with his mother Rosie Herrera. (Photo: Daisy Herrera, Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

O'NEILL: And what have you been hearing from currently incarcerated firefighters about this bill? You know, how have they been reacting?

HERRERA: So it is huge. And the feedback is, it's life changing because now they're able to do the stuff that they've been wanting to do, which is pay restitution, so they don't have to worry about upon release, that hindering from being off of parole, which is very huge, because that's another obstacle you have to overcome when you're trying to get a job. So it opens up a lot more avenues as far as employment. So that's huge. And so majority of them, I would say, are very, very excited to see that first check and see what it looks like. But more importantly, I can't emphasize this enough, the word that is being used a lot is to be seen. You know, to be seen. It demonstrates that you are no longer defined by your mistake that you made. You can take accountability, responsibility for it, and demonstrate to society, to the public and your victims, that the way you make amends is by giving back and being of service, right? So it's not throwing the key away and just say, "Hey, we're done with you." Well, no, 90% of the population that's incarcerated right now will be coming home, so this is part of that rehabilitation.

O'NEILL: Well, so, this is obviously a massive change in the amount of money that these incarcerated firefighters are going to be paid. What kind of system do you think needs to be in place in order to help these firefighters take full advantage of this wage increase?

According to Herrera, the public’s response to the Palisades and Eaton fires was key to the passage of bill AB 247 because they saw incarcerated firefighters in action. Here is a photo Herrera provided of a firefighter handling the Eaton Fire. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

HERRERA: So what we are currently working on right now is presenting and offering financial literacy and money management classes. So now at all fire camps, this will be a curriculum that can be presented to them. So then, therefore individuals that will be making this money can now actually make educated, informed decisions of what to do with this money that they will now be receiving. And I think that that that is important because I believe the public would want to know also what's going to happen with that money. And I feel like as a taxpayer, I would feel better knowing that individuals that are going to be making more money while they're incarcerated are not going to foolishly spend that money. I believe that we, all in this world, can use, you know, some financial literacy and money management, right? So why not an individual that's still going to be able to have an opportunity to save a lot of money?

O'NEILL: From what I understand, the general public's response to the Palisades and Eaton fires earlier this year sort of helped push this bill along. Talk to me about that.

HERRERA: Yeah. So it definitely did because a lot of individuals that were affected by it were individuals of power, and they got to see firsthand incarcerated firefighters fighting fires alongside career firefighters. So to visually see that was very impactful for them because now they're able to put a face and put an image to what they did not know about before, which was incarcerated firefighters and what they do. And so, as you know, when you're in need of help, you don't question, you know, who's the one that's helping you. You just need help, right? So this was huge in the sense that it affected Los Angeles County. And Los Angeles County showed up. The people spoke and demonstrate that they were willing to pay, as far as wages go, for individuals that were actually there saving their homes and lives.

O'NEILL: Eddie Herrera Jr. is a fire apparatus engineer for the state of California. Eddie, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

HERRERA: Thank you for having me. I appreciate you and looking forward for greater things to happen for us.

Related links:

- Our guest, Eddie Herrera Jr., regularly works with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition. Learn more about them here

- Listen to our original story about Eddie Herrera Jr. and incarcerated firefighters

[MUSIC: The Dip, “Chanterelle” on Won’t Be Coming Back, The Dip]

Wildfire Trauma and Recovery

A sunset tinted red by wildfire smoke, as seen near the Doering family cabin. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

O’NEILL: So of course, extreme wildfires take a huge physical and mental toll and Jenni, I think this is where things get a little personal for you.

DOERING: That’s right Aynsley. As you know, I grew up in San Diego. And in October 2003, back when I was still in middle school, the Cedar Fire exploded to hundreds of thousands of acres right in and around the city. It was so dry that fall that my wonderfully eccentric English teacher led us in a “rain dance” which, now that I think about it, was likely a bit culturally offensive… but anyway, within days that fire sparked.

O’NEILL: Oh Jenni, I hate to be a bit glib, but that must have been a pretty bad rain dance.

DOERING: I mean I guess so. You know, it’s dark, but you have to find ways to laugh about it afterwards. I mean, neighborhood after neighborhood was literally being ordered to evacuate as the fires advanced and left behind only chimneys. The sky was so dark in San Diego, the sun was red, there were ashes falling like some kind of weird SoCal snow. And my family never did have to evacuate, but the fire got really close.

The woods around the Doering family cabin, December 2016. Some of the oaks had to be cut down but most survived the Cedar Fire. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

O’NEILL: Oh, that’s so scary. I mean it sounds downright apocalyptic.

DOERING: It really was. And it’s weird, thinking back on it, as a kid that felt like such an extreme and one-time trauma, like something that would never happen again. But now I know that these disasters are becoming much more common thanks to climate disruption, and so that’s a whole other layer of heartbreak that I’m still coming to terms with.

O’NEILL: I can only imagine, and I mean given how common wildfire smoke is these days, I’m wondering if that might be a bit triggering for you?

DOERING: Yeah, I mean I think so, and you know, you can’t help but be reminded of those very frightening Cedar Fire days even from just a whiff of wildfire smoke. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m OK, but it’s really a relief to find researchers who are studying not just the mental health impact of wildfires but also strategies to help people cope, researchers like Jyoti Mishra who we had on the broadcast back during the Los Angeles Fires in January 2025.

The ghostly limbs of a large Manzanita bush that succumbed to the Cedar Fire in William Heise County Park, but re-sprouted lush new growth in the years afterwards. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

O’NEILL: Yes, Jyoti is a co-director of the University of California Climate Change and Mental Health Council and associate professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego. And she’s studied mental health impacts in the aftermath of the 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California and the 2023 Maui blazes in Hawaii.

MISHRA: We see that not surprisingly, individuals' mental health is greatly impacted and people show varying degrees of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression. And the brain kind of goes into a hyperalert stress state and so it's difficult to focus on tasks on hand.

DOERING: You know, it’s been a long time since I lived through a major wildfire but I really do remember that hyperalert feeling.

The 2018 Camp Fire was California's deadliest and most destructive wildfire to date, burning over 153,000 acres and destroying nearly 19,000 structures, including the town of Paradise. (Photo: Pierre Marcuse, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: And you know in terms of resilience strategies, when Jyoti studied people who had survived the Camp Fire in California, one-third showed those distress symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression or being hyperalert. But the other 70% who had shown more resiliency had a couple key things in common.

MISHRA: Taking care of your physical self is very important, having good sleep hygiene, being able to sleep well, being able to exercise is very important. And then we've also found that people who were more mindful, that is people who practice more present moment awareness, those people did better. And then finally, a really important factor is social connection, being connected to those in your family and in your community and having a great support network around you, can really protect you from such a catastrophic event.

O’NEILL: I mean it rings true, and we hear over and over again with disasters, it’s the importance of community.

DOERING: We need each other for sure. You know, Aynsley there’s one more thing to share. The cabin my grandparents built in the mountains east of San Diego, our beloved weekend home tucked in a pine and oak forest, was in the direct path of the fire. And we thought for sure it was a goner.

Dr. Jyoti Mishra, Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego. Dr. Mishra is also the founder of the Neural Engineering and Translational Labs (NEATLabs), where she leads research on mental health. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jyoti)

O’NEILL: Oh but it survived? How?

DOERING: Well, firefighters were able to spray it with fire-retardant foam just in time before the flames swept right through. And Aynsley, knowing what I now know about PFAS in firefighting foam… well… that’s a complicated mix of emotions to unpack.

O’NEILL: I bet, it comes with all those health concerns. So, instead of what, out of the frying pan and into the fire… now you’ve got a… what, out of the fire and into the nonstick frying pan of forever chemicals?

DOERING: Yeah, I guess that’s one way to put it! Well, whatever was in it, that foam must have really worked because the fire burned so hot at the cabin that there were still live coals smoldering between oak tree trunks a whole week later.

O’NEILL: Oh my gosh, wow. That is intense.

DOERING: Yeah, and honestly, the trees looked dead. But before long, most of those oaks sprouted new green leaves as the forest started to recover from that trauma. And eventually, so did we.

Related links:

- Learn more about Dr. Jyoti Mishra.

- Read the study “Climate trauma from wildfire exposure impacts cognitive decision-making.”

- Learn more about NEATLABS, where Jyoti Mishra is co-director.

[MUSIC: Electric Light Orchestra, “Mr. Blue Sky” on Out of the Blue, Epic Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment]

DOERING: Just ahead, some Oregon streams are bouncing back to health after the 2020 megafires. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Spyro Gyra, “Catching the Sun” on Catching the Sun, Amherst Records]

Stream Life is Thriving 5 Years After Oregon Fires

In July 2025, a field crew brings electrofishers to Oregon’s Cook Creek. The crew is counting fish and other aquatic life for later scientific analysis of how the stream’s ecosystem has recovered in the years since Oregon’s Labor Day wildfires of 2020. (Photo: Evan Rodriguez, OPB)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In 2020 Oregon faced its most destructive wildfire disaster, when more than a million acres burned in the “Labor Day” fires. After the firefighters finally headed home, it was the scientists’ turn to head out into the woods. The sheer size and severity of those fires gave them a unique chance to learn what happens after a massive burn. Science Reporter Jes Burns of OPB has the story.

BURNS: Sometimes, to understand what’s happening in a stream, scientists have to go fishing.

LEER: I'm ready whenever – fire in the hole.

[SFX AMBI Beep/AMBI Beep and Splash]

BURNS: Field crew leader David Leer is knee-deep in remote and rocky Cedar Creek east of Salem.

LEER: Fishy, fishy. Oh, I saw one.

BURNS: The forest around the stream burned in the 2020 Beachie Creek Fire – one of the Labor Day Fires.

[SFX AMBI Beep/AMBI Beep and Splash]

BURNS: The beeps come from his bulky hard-plastic backpack. He waves a metal probe in the water in front of him.

LEER: If you can hear the beeping, you put your hand in the water, you're probably gonna get a little jolt.

BURNS: This is electrofishing.

SWARTZ: Electrofishing is temporarily stunning the fish in the water and then snatching them up as fast as you can in the net. You know, we look like a Ghostbuster.

BURNS: Allison Swartz is an Oregon State University stream ecologist.

SWARTZ: The fish are doing their best to hide from us.

LEER: There’s a fish 3 o’clock, I think.

SWARTZ: Yep, yep, yep, yep, yep, yep

LEER: Nice. There it is right there.

SWARTZ: I think that was a rainbow trout.

BURNS: All the fish, tadpoles, crayfish and giant salamanders they catch will be counted, weighed and measured before being released back into the stream. The data are helping the team understand how streams changed following the Labor Day Fires. US Forest Service biologist Brooke Penaluna.

Oregon’s 2020 Labor Day fires included five megafires, including the Beachie Creek Fire, which burned nearly 200,000 acres east of Salem. Pictured above is affected land near the Santiam River in August 2025. (Photo: Evan Rodriguez, OPB)

PENALUNA: So this study is unique in that we have 30 streams, you know, across 3 big mega fires in Western Oregon.

BURNS: The streams they’re studying are diverse. The Labor Day Fires burned around them at different severities. And the forests they’re in have been managed in a variety of ways – there’s tree plantations, more natural mixed aged forests, areas where the burned trees were salvage logged after the fire, and some unburned streams for comparison, says Swartz.

SWARTZ: The reality is that wildfires are increasing on the landscape in severity and size, and so in terms of understanding how we manage our forests and these ecosystems, we need to know what's happening because we're really just kind of at the start of what we're going to begin to see in the future.

LEER: Ok, get ready. This is going to get exciting.

BURNS: Every summer since the fires, crews have tested water quality and how the animals in the streams have fared.

LEER: Fish in your net. Out of your net. Going down. That was brutal. It jumped right in your net, then jumped out. Then gone.

BURNS: Many of the species depend on clean, cold water to flourish. But much of what’s left around Cedar Creek are trees like charred matchsticks. Without the canopy, the sun beats down on the water much of the day. Yet Swartz has started seeing some surprising trends.

SWARTZ: Despite stream temperatures getting really warm in these systems after the fire, the fish populations are remaining just as high or higher than the unburned sites.

BURNS: The researchers are still unpacking exactly why. One theory is that more sun means more algae, which feeds the food web. Also without trees and vegetation sucking up the water on stream banks, there’s more left for the rivers, says Penaluna.

A coastal tailed froglet, pictured mid-transformation from tadpole into adult frog. Coastal tailed frogs are one of the species that live in stream ecosystems throughout the Oregon Cascades. (Photo: Evan Rodriguez, OPB)

PENALUNA: With the extra rains that are coming straight down and into the stream - with that runoff - you're getting additional fringe habitats along the streams.

BURNS: And it’s not just fish. Preliminary results are showing that the wildfires haven’t caused declines in amphibians either. But the researchers have seen fewer frogs in places where heavy post-fire salvage logging happened. For the longest time, stream ecosystems were thought to suffer because of wildfire. But in the five years since the Labor Day Fires, these scientists are seeing signs that the trout and other species that call the Cascades home are thriving.

PENALUNA: Essentially everything we thought we knew about fire, we've kind of turned it on its head here on the west side of Oregon.

BURNS: And the research shows that the tragedy of the Labor Day Fires has turned into an opportunity. A chance to figure out the best way to manage our forests after wildfire to protect our streams and all the life they contain.

LEER: Yup, it’s right here. Right here. That’s a different fish.

DOERING: That story comes to us from Jes Burns of OPB, Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Related link:

This story at the Oregon Public Broadcasting website.

[MUSIC: Paper Planes, “Hopeful” on Simple Things, Paper Planes]

"Good Fire": How Cultural Burning Heals Land and People

Cultural burning hands-on practice during a fire camp at First Nations’ Emergency Services Society of British Columbia (FNESS) in Cranbrook, BC. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

O’NEILL: To combat increasingly dangerous wildfires, modern fire management teams may use prescribed burns to reduce fuel buildup before fire season begins. But around the world, Indigenous people have been using fire on the landscape for thousands of years. One such practice comes from the Métis tradition in Western Canada. While a prescribed burn is typically a larger, low to moderate-intensity fire, the Métis burning practice is much smaller, more closely resembling a campfire, and it carries cultural significance. To learn more, we turn now to Cree-Métis scientist Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson. She's a senior fire advisor with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. Amy, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHRISTIANSON: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So tell us, how did you get involved in this world of fire stewardship?

CHRISTIANSON: I just remember growing up having lots of my family involved in firefighting. Back then you know, we had fires all the time, but they weren't like scary fires. But I’d never actually really thought much about it until I moved down south to an urban center, and then I realized that that wasn't really like a normal life experience for a lot of people. And then I started really working with Métis elders during my PhD and just started hearing this concept of “cleaning the land.” And really got interested in rediscovering my own family's role in use of fire, but then also just how this could be a, you know, a potential solution for our current wildfire crisis.

O'NEILL: Now, many of us might be familiar with this concept of “prescribed burn.” How would you say that is both similar to or different from a Métis or Indigenous burning practice?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so you know what, they're both very important practices but they're also like apples and oranges and so lots of people use the two terms interchangeably, but really they're very different conceptually, like for Indigenous people, like when we use cultural fire, it's around Indigenous governance systems and knowledge of when to burn, and it's done to achieve cultural objectives on the landscape, so things that we need to sustain our cultures. There's hundreds of reasons why Indigenous people burn. I mean, I think some of the most common and shared are, you know, burning for berries. So for example, berry bushes often get overgrown as they age, and when we go in with fire in the early spring or late fall, it's almost like pruning those berry bushes. You kind of burn the dead parts of them that aren't producing, but you leave the roots intact. So then the next spring, they put up really healthy new growth. And then for cultures that rely on bears, the bears are attracted to the new berry growth. So it almost like lures the animals into that area. And then in the end of the summer, you know, you get really nice fat bears to harvest. Prescribed fire is done for quite a different reason. It's usually to reduce hazard, so to, you know, remove vegetation and other things. It also generally follows quite a paramilitary approach. You know, it's dominated by white men, and, you know, there's lots of equipment and helicopters and, I mean, there's nothing wrong with that. The fires that they're doing are usually higher risk than the cultural burns that we do. So they're both very important practices, but just quite different in how they're actually carried out on the land.

Prescribed burns are large-scale operations requiring permits and careful planning. These burns are higher-risk than the Métis practice, and are carried out by teams of firefighters and may involve the use of helicopters to ignite and put out the fire. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: How did colonization change burning practices across Canada?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so when settlers first came to Canada, they saw trees back then as money signs, right? They didn't understand, you know, why you would want to potentially burn in an area. So they brought these fire exclusion policies, and the first one in Canada was actually in 1610, in Newfoundland. So that made Indigenous burning illegal. And then there was also, like, the campaign of systemically removing Indigenous people from their lands. So through the Indian Act we have in Canada, through putting people onto reserves, through residential schools, all of those things basically led to this huge severance of our knowledge systems.

O'NEILL: And what kind of pushback have you faced against these cultural burning practices over the years?

CHRISTIANSON: You know, there's all sorts of Acts and regulations and other things in place right now that keep us still from burning as we need to do on the landscape. Even amongst our communities, there's a reluctance or a fear of fire, because we've been told for so long that that's not an appropriate practice to carry out on the land. So I think for me, you know, that's been one hard thing to watch, because we need fire. We need fire on the landscape, and what these out-of-control fires are showing us is that we're not stewarding forests properly.

O'NEILL: I'm curious how you would say your participation in burns is tied to or influenced by your relationship with the forest or nature just on a general level?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, you know, I think that it's implicitly tied. Because if you don't have that relationship, you don't understand why fire would be needed, and you don't understand then how that vegetation and other things might respond to fire. Like, one thing that's really important for us when we're using fire is, you know, thinking about nesting birds and other things, if we know that they're there we don't want to burn that area, right, because we're basically burning up their nests. So there has to be, like, that cultural tie to the landscape. When I go burn too, like, usually I go with my husband and my kids, it usually takes us two or three hours, so kind of an afternoon activity. We don't use, like, a ton of water, anything, because we have, like natural fire breaks, like snow lines or other things there. Actually, my daughters, I think, kind of find it boring, like after you like light it, because it's like a very, very controlled activity. And so that's one thing I often hear as a criticism for cultural burning is that, like, there's no training required, or there's no planning required, and that's incredibly insulting, because for us, like the training comes from, you know, years of working with people who are more knowledgeable than us with fire, and then, you know, the planning is done endlessly. It's something that we're constantly looking at and observing the land as we decide when and where to put fire. The positive side is, you know, that I just love being out there, and just because cultural burning is a slow activity you like, here are the birds, you notice the trees. Like, I'm pretty familiar with most trees on my property, which I know people might think is crazy, but like, I know, like, you know, I can see them and I can tell if they're like sick or if things are, are different about them. So that's the thing I like most, is just being out there and continuing that relationship.

When Métis people put fire onto the landscape, it’s on a much smaller scale than most prescribed burns, often described as a fire you can walk beside. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

O'NEILL: And now, of course, many of us do consider fire frightening, dangerous. How do you protect yourselves from the potential dangers of being around large-scale fire?

CHRISTIANSON: So I think for us, when we're talking about cultural fire, it's usually a fire we can walk beside, is another term that we use for it. So like, when we go out, it's almost like a campfire moving across the ground, like that's about the scale of it. So for me, like I don't feel scared or like it's dangerous, it's really kind of quite a nice calming practice that we do. Most cultural burners I know have never had an escape fire, but you always have that in the back of your head like, well what if, and so I would say that I burn with way more caution than I used to, because of this and because of my role in like the advocacy components of it. You know, for me, what that does is because we're removing that dead, dry vegetation from the landscape and promoting a healthier environment, that's really where then when we see these out of control fires, it's much easier to stop the fires. So, you know, as a fire is coming towards my area, because I have burned and we have, like, a lot less dead vegetation that the fire can basically eat as it's moving towards us, it makes it easier for firefighters then to put out the fire. So, yeah, it's proven to reduce wildfire risk to communities from out-of-control fire.

O'NEILL: So your podcast is called “Good Fire.” What is good fire?

CHRISTIANSON: So with good fire, you know what we're trying to do is produce like a mosaic landscape. You know you have old growth forest and you know older trees, but then you also have, like, meadows, and you have younger trees, and you have a mix of deciduous trees and coniferous trees, so like leafy trees and needle trees. And the reason we do that is so that we have less far to travel to access, like the cultural resources that we need. And when I'm talking about bad fires, what I'm talking about is these like climate change-induced fires that are burning at such high intensity and with such severe impacts that they're really devastating the forest for generations.

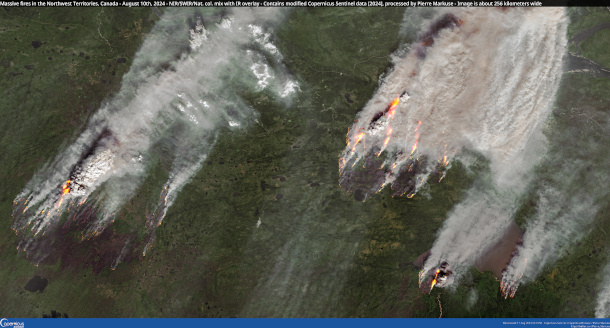

Satellite imagery of smoke from wildfires spreading through Canada’s Northwest Territories, August 10, 2024. (Photo: Pierre Markuse, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And now your fire knowledge is not just from Métis cultural practice. You also have a history with Western-based science education and research. How have you combined those two, the Indigenous practice and the Western practice?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so I did my PhD, actually with the Métis community, learning about cultural fire and then I went and worked for the Canadian Forest Service and there I was a fire social scientist for almost 14 years. And so what I found was, when I started, I was very idealistic, and I thought, you know, if we just have, like, a really good Western scientific paper or something like that, it'll change people's minds and let us be able to start burning, and so I would say that we've produced paper after paper on that and have actually seen very little change. And what I then realized is really it's an issue of power and systemic racism that we're experiencing. It's not a lack of scientific knowledge or Indigenous knowledge. It's really much bigger things at play that are keeping us from being on the land. A lot of discussion about, you know, how we allow Indigenous people to burn, but really, like, burning is an inherent right, it's not something that people allow us to do or not. So I got offered a position at Indigenous Leadership Initiative, which is really an advocacy-based conservation organization that's Indigenous-led. And so here we're really trying for action now, so to really target policies, regulations and other things that are keeping us from being able to burn. And so we're not obsessed with fire. We're obsessed with like, healthy landscapes, and fire is one way that we can get to that. And you know, when I'm even speaking about cultural fire now, like, I show videos behind me of cultural fire, because usually once you show it, then people are like, I had one lady come up to me and be like, oh, that's all you want to do. And it's like, yeah. Like, it's not like, you know, we want to go and start like, you know, mountainsides on fire, although maybe there's some elders that eventually would want to do that. But you know, for us, it's just having a lot of fires on the landscape that are small and are controlled that produce these mosaics that we want to see.

O'NEILL: And in what ways have you seen successful collaboration between various different Indigenous groups and also perhaps non-Indigenous groups when it comes to fire management?

Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is Cree Métis, and grew up in Treaty 8 territory in Northern Alberta. She is a Senior Fire Advisor for Indigenous Leadership Initiative and co-hosts the Good Fire podcast, which looks at Indigenous fire use around the world. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

CHRISTIANSON: Yes I think probably the best example is I've worked quite a bit with the Blood Tribe over the last five years. So they're down in southwestern Alberta. Alvin First Rider and his team there have been working really hard to establish a fire guardian program, and they've done that in partnership with Parks Canada. And I think what's been great there is that Parks Canada has been a really good supporter, but not trying to control, if that makes sense. And I think part of that is because, at the moment, the guardians aren't trying to burn directly in the national park, but they've been coming out and supporting burns on the reserve, and it was a really great experience working with them. And the Blood Tribe program has just been inspirational and I hope that we see it replicated across Canada. You know, because of the changes to the forest and climate change in many areas like we can't just go out and put cultural burning back on the landscape like we used to. Those areas need either a prescribed fire or mechanical thinning, or hand thinning to remove a bunch of that vegetation that's in those areas because if we went and tried to do a cultural burn there using the techniques we usually use with community, it would just be way too big of a fire for us to control. But to me, that also speaks to where really good partnerships can come in, you know, like if an agency that has access to heli torches, you know, where people don't actually have to be in the fire, they can just drop fire into an area and they have all the firefighting equipment and other things, if they can go into those areas and burn them first, then we can slowly begin to bring cultural fire back to that area in a safe and sustained way.

O'NEILL: And how can this Métis burning practice be a tool for healing or cultural connection among Métis people?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah. So I really think the beauty of it is just getting people out on the land together and really being proud of their culture. So any workshops that we've had where we've brought Métis people together, it's just been a wonderful experience, especially we've done a few with youth, where we go out and, you know, teach youth about why this practice was important. And most have really no idea that Métis people used to burn like this. It was an important part of the buffalo hunt and trapping. The other thing that I've really liked about it is just being able to work so closely with like our relatives, like the First Nations, because really, you know, we're related to those folks. We use fire in similar ways to them, and it's really been a wonderful, like, way of unity, if that makes sense. Like there's so many, you know, divisive things in the world, but when you really get people out on the land and learning and being with one another, it really helps, and for, you know, mental health, physical health and other things of people who participate.

O'NEILL: Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is a senior fire advisor for Indigenous Leadership Initiative. Amy, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, thanks for chatting with me.

Related links:

- Métis National Council | Video: "Métis National Council Wildfire Workshop"

- More on Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson.

- Learn more about the Good Fire podcast.

[MUSIC: Métis Fiddler Quartet, “Teardrop Waltz” on North West Voyage (Nord Ouest), Métis Fiddler Quartet Productions]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth