June 6, 2025

Air Date: June 6, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Hurricane Forecasting in 2025

View the page for this story

The 2025 hurricane season is underway, and experts say the U.S. is likely to see higher than average activity. The past couple of years, extremely warm water in the Gulf of Mexico helped storms rapidly intensify into major hurricanes. Ryan Truchelut of consulting firm WeatherTiger talks with Host Aynsley O’Neill about what’s in store this season and how cuts to federal weather monitoring and hurricane modeling could leave the U.S. underprepared for strengthening storms. (13:57)

Saving Corals Amid Record Bleaching

View the page for this story

Record-breaking heat in the oceans has led to the most widespread coral bleaching event ever documented, ongoing since January 2023. Bleaching weakens the corals and many end up dying, but others can recover and even thrive amid hotter oceans. Steve Palumbi, a Professor of Biology and Oceans at Stanford University, joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share how researchers are finding ways to help corals survive and thrive as the oceans warm. (12:46)

Protecting Farmworkers from Wildfire Smoke

View the page for this story

Poor air quality from wildfire smoke and other pollutants can harm cardiovascular health and also make farmworkers more prone to work injuries, according to researchers. But in California, requirements for employers to hand out face masks do not kick in until the air quality has already deteriorated past the point where farmworkers are experiencing impacts. Reporter Rambo Talabong of Inside Climate News spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about proposals to better protect farmworkers from air pollution. (09:46)

Keeping the Vjosa River Wild

View the page for this story

The small Balkan nation of Albania already produces 99% of its electricity from hydropower and has plans to become a major exporter of hydro, threatening some of the last free-flowing rivers in Europe including the Vjosa. The 2025 Goldman Environmental Prize winners for Europe were able to stop a dam on the Vjosa River and convince the government to designate Vjosa Wild River National Park. Co-recipient Besjana Guri joins Host Jenni Doering to share how they achieved this victory. (08:25)

Listening on Earth

/ Sophia PandelidisView the page for this story

Living on Earth Producer Sophia Pandelidis is living and working remotely from Greece and sent in the sounds of church bells and festive bouzouki music in a café on the island of Paros, which is in the Aegean Sea between Santorini and Mykonos. (01:18)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250606 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Besi Guri, Steve Palumbi, Rambo Talabong, Ryan Truchelut

REPORTERS: Sophia Pandelidis

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Scientists look for solutions as extreme heat endangers coral reefs.

PALUMBI: Remember the Taylor Swift song, “Cruel Summer”? Well, we’ve had two “cruel summers”! ’23, ’24 — what are we going to see in ’25? That report from NOAA is a sort of clarion call that “cruel summers” are happening more and more frequently, and it’s affecting these corals.

DOERING: Also protecting one of the last wild rivers in Europe.

GURI: Our vision was stop the dams, declare a national park, and sometimes it even felt like really not very possible to achieve, but we stick to the plan, and we managed to bring in scientific arguments why the Vjosa is so unique and why it should be protected.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Hurricane Forecasting in 2025

The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season is predicted to have slightly above average activity. The aftermath of 2024 Hurricane Helene in North Carolina is pictured above. (Photo: NCDOTcommunications, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

In 2024, five major hurricanes made landfall in the continental United States, wreaking havoc as far inland as Asheville, North Carolina. At least 250 people died because of Hurricane Helene, making it the deadliest hurricane to strike the U.S. since Katrina in 2005. Now, the 2025 hurricane season is underway, and experts say we’re likely to see slightly higher than average activity. One of these experts is Ryan Truchelut, Co-founder, President, and Chief Meteorologist for the consulting firm WeatherTiger, and he joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Ryan!

TRUCHELUT: Thank you for the invitation, and happy hurricane season.

O'NEILL: Happy hurricane season. And I guess the question is, how much of a happy hurricane season will it be? I saw we might be expecting a little higher than normal activity. What would a season like that look like?

TRUCHELUT: Well, as a seasonal forecaster, I always try to stay very focused on landfall risks, because we don't so much care about how much hurricane activity happens out in the open ocean. What we care about are the human and economic impacts of these storms, which are very significant. We've done almost a trillion dollars worth of economic damage in the continental United States just in the last 15 years from landfalling hurricanes. In a typical Atlantic hurricane season, the United States averages one to two hurricane impacts per season. Major hurricanes, those are category threes, fours and fives, you get one of those on average about every other hurricane season. So there's about a 50-50 chance in an average hurricane season, if you're going to get a category three or above. In this hurricane season, those odds being tilted in a slightly more active, slightly riskier direction than normal, puts us in a ballpark of probably about a 50% chance of either two or three US hurricane landfalls in the upcoming season, as opposed to that one to two typical number. And then, as opposed to the 50% average chance of a major hurricane landfall, we have maybe a 55 or a 60% chance of a major hurricane landfall somewhere in the continental US in the upcoming season. Now, just because I know that listeners are probably thinking about it, there's only about a 5% chance that the 2025 hurricane season would equal those five US hurricane landfalls that we saw in 2024. So we're not looking more than likely at another year like 2024, but we are looking at a year that's likely to have some significant impacts on the continental United States.

Hurricane Helene reached as far inland as the mountains of North Carolina in 2024, washing out numerous roads and bridges. Truchelut says there is only around a 5% chance that the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season will equal the five major hurricane landfalls seen in 2024. (Photo: NCDOTcommunications, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And Ryan, to what extent is climate change and increasing global temperatures, how are those affecting what we're likely to see in 2025 and beyond?

TRUCHELUT: Sure. Well, I think that there's definitely a climate change fingerprint on the sea surface temperatures that we saw in 2023 and 2024 because they were so far beyond other warm years in the historical record. You simply would not be able to get sea surface temperatures that warm over that large an area without there being some unnatural influence of increased, basically, radiation capture, because we're changing the chemical composition of the atmosphere, we're changing the concentration of greenhouse gasses. You know, overall, this is a tricky question, because there hasn't been a overall trend towards more hurricanes, tropical cyclones worldwide in the past 30 or 40 years in the period of the historical record we can trust. It does seem like there's been more hurricane activity in the Atlantic, specifically. For individual storms, you can definitely say that there is some influence going on when you look in the aggregate.

O'NEILL: So while there may not be more hurricanes per se, you know, to what extent is climate change impacting, you know, the strength of these storms?

TRUCHELUT: Climate change is definitely having an influence on the human impacts of individual storms. And I think a really evocative example of this is Hurricane Helene last year, because one of the things that scientists have high confidence in saying is a change in how hurricanes are developing and how hurricanes are moving and the impacts that they're having from climate change is in terms of precipitation. We know that hurricanes are producing more precipitation because the atmosphere is warming, warmer air can hold more water vapor and transport it inland. So for a hurricane like Helene, the fact that it was moving over waters that were two or three degrees warmer than they would normally be in late September in the Gulf, and the fact that it was moving 30 miles an hour when it came inland, allowed it to transport an enormous amount of moisture, far more than any other hurricane in the historical record, north across the southeastern United States and into the mountains of North Carolina, and resulted in an unprecedented devastation across that region. So we have always had hurricanes in the Gulf, and we always will have hurricanes in the Gulf, but they're a little bit stronger by virtue of climate change, and they're creating more precipitation and thus more human impacts because of climate change.

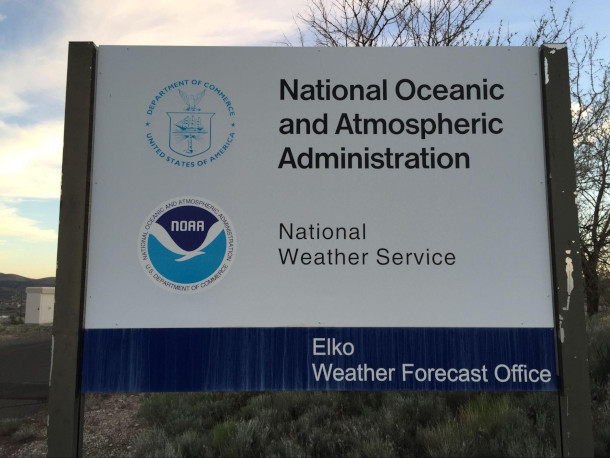

Cuts to government agencies like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service will put a strain on resources for storm readiness in 2025, according to Truchelut. (Photo: Famartin, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

O'NEILL: Now Ryan, this prediction for a slightly higher activity hurricane season, it's coming at a time when the Trump administration is cutting staff and programs at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, and the National Weather Service, NWS. So how will moves like this affect the country's storm readiness?

TRUCHELUT: Well, in several different ways. For one, the job cuts at NOAA and the National Weather Service are stretching this organization very, very thin. So National Weather Service has a network of over 120 field offices across the United States where forecasters are on the ground in communities. Every one of those offices operates, 24/7, 365. They are on call around the clock, providing both routine and emergency weather forecasting. And unfortunately, because there's been so many job losses in many of these offices, several of them are no longer able to be staffed 24/7, which is a real break with the tradition of the National Weather Service. They simply don't have the people in place to be able to do their job. And a lot of these offices that are lacking key leadership are along the Gulf Coast. They're places like Houston, Tampa Bay. These are places that are vulnerable, that have been hard hit just within the past decade. So we don't have the staff in place to communicate the threats to the public in the way that we typically do. By virtue of cutting staff, we've also reduced the number of weather balloon launches that are occurring across the United States. The data that goes into a model is so crucial for getting good forecasts out of it. So if you don't have a good initial snapshot, initial picture of what's going on in the atmosphere, even the very best atmospheric model is not going to be very useful. So by cutting down on our key observational networks, we're hobbling our ability to make accurate forecasts. We've also made cuts to our research divisions that focus on things like developing better hurricane models, cutting our hurricane hunter forces and personnel. So we're vulnerable, and I can only hope that we won't be tested beyond our breaking point in the upcoming season.

O'NEILL: Well, so Ryan, with these impacts at the federal level, what tools do weather forecasters have at their disposal that they can still use to help communities in 2025?

The National Severe Storms Laboratory’s first Doppler Weather Radar located in Norman, Oklahoma. Private forecasters are dependent on these kinds of public resources. (Photo: OAR/ERL/National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL)., Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

TRUCHELUT: Sure. Well, you know, I want to emphasize that I'm a private forecaster. I run a private company. I'm not affiliated with the government, but like every forecaster, the tools that I'm using to do my job and give, you know, basically, more specific information to specialized clients, everything I'm doing is predicated on data and resources from the public sector. I'm totally dependent on NOAA hurricane modeling. I'm totally dependent on radar networks, on satellite networks, observations, historical data sets that are all maintained at no cost and made open source, made available directly to the public by NOAA and the National Weather Service. So you know, these things that we have, we've built them over a long period of time. You know, Rome wasn't built in a day, and it can't be taken apart in a day, either. So you know these tools, they are still available for now, but we certainly need to appreciate that these are all institutions that require maintenance. They require staffing. They require public resources to be invested in them, because all that investment has a huge payoff for society at large. It pays for itself so many times over to invest in public safety and invest in disaster resilience and disaster response. And I know hurricane forecasters in both the public and private sector, we will do our very best to provide the public the best information that we can this year, you know, no matter what, but please don't take away the tools that we use to be able to make those forecasts.

Our guest Ryan Truchelut advises listeners to have an emergency evacuation plan in place far before storms make landfall. (Photo: Andrew Heneen, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

O'NEILL: Now for those of us out here who are in areas that might be vulnerable to hurricanes, what actions should we be taking? What actions are in our control in order to head into this 2025 season well prepared?

TRUCHELUT: The best single piece of advice that I can give someone who is in a hurricane threat area, which is basically all of the East Coast and southern coast of the United States, you need to be aware of what you would do if you were called upon to evacuate. So you don't want to be coming up with a plan when you are scared, there's a storm out on the water, and you don't know what you're going to do. You're not going to make the best decision for yourself or your family. So think about it ahead of time. Have an evacuation plan. Have an emergency kit that has several days worth of food, water, cash, medication, basics that you need to keep yourself safe.

O'NEILL: Now, Ryan, let's step back for a second. Where are we in this current climate moment as a society, and to what extent are the threat of more intense storms or flooding, or even things like wildfires, all fueled by climate disruption, to what extent are those things changing how we feel and how we act?

TRUCHELUT: Well, I think that the last 10 years, as a resident of the Gulf Coast, we've had an unprecedented run of major hurricane landfalls here. We've had 10 major hurricane landfalls since 2017. That's the most that there have ever been in a 10-year period here. Cumulatively, those storms have done over $700 billion worth of damage. So I think there's a sense here, even amongst people who aren't necessarily predisposed to believe, quote, in climate change, that the present is not like the past. You know, I go out and speak to all sorts of audiences, you know, out in, I'm an agricultural meteorologist, too. So I talk to farmers, I talk to people who fish, who live on the Gulf Coast, and they know that the water temperature in the eastern Gulf of Mexico should not be 88 degrees late in September. It's not normal. These are people who have gone out and they've lived in nature. They're familiar with the natural environment, and they know when things are different. Farmers know when they are planting their crops. They have good records of this going back decades and decades, and they're planting their crops earlier and earlier because the frost dates keep moving earlier in spring. So I guess what I would say is, I think we're at the place where experience is the best teacher.

Part of an evacuation plan can include creating an emergency kit that includes food, water, medication, and other essential items. (Photo: Jennifer Smits, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

O'NEILL: Ryan, it seems as though it's not really even a matter of living in a new climate normal at this point. The situation is constantly changing. How have you dealt with that reality over the course of your career?

Ryan Truchelut is co-founder, president, and chief meteorologist for WeatherTiger, a group of professionals dedicated to advancing the science of forecasting. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Truchelut)

TRUCHELUT: So it's been a bit of a challenge to wrap my mind around this, because I'm a hurricane climatologist. When I went to graduate school, all my dissertation research was going back into hurricane history, learning what we can from it. So I have a very clear sense of what history teaches us about hurricane activity and sort of what the bounds are. And as a forecaster, as someone who actually is down in the trenches writing forecasts, you know, advising people about how to respond to the storms of the past 10 years, I have been floored over and over again by things that simply have no reference point in the historical record happening. And as a forecaster, it feels almost irresponsible to forecast something that's never happened before. It makes me deeply uncomfortable, as a scientist, to be going outside that realm of what's happened in the past. Unfortunately, there are simply more things in the mix as a possibility in the year 2025 than there were in 1870 or 1900. The odds have shifted towards increasing probability of a storm intensifying rapidly in the last 24 hours before landfall, increasing probability of certain precipitation thresholds being reached in cities along the Gulf Coast of heavy rainfall coming from tropical cyclones. So it's been an adjustment, and I would say that as these extraordinary and rare events have happened with increasing frequency, I'm more comfortable at making forecasts now for something way outside the bounds of the historical realm, because it simply happened so much in the past 10 years that I'd be foolish not to be a little more willing to go further out on a limb.

O'NEILL: Ryan Truchelut is Chief Meteorologist at WeatherTiger in Tallahassee, Florida. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: Take care and stay safe this season.

Related links:

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | “NOAA Predicts Above-Normal Atlantic Hurricane Season”

- E&E News | “Chaos at FEMA, NOAA as hurricane season starts”

- Learn more about WeatherTiger

[MUSIC: Ellie Johnson Trio, “Stormy Weather” on Street of Dreams, Ellie Johnson Trio]

DOERING: Just ahead, scientists brainstorm solutions to help coral reefs adapt to extreme heat. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ellie Johnson Trio, “Stormy Weather” on Street of Dreams, Ellie Johnson Trio]

Saving Corals Amid Record Bleaching

Dr. Steve Palumbi samples corals in the country of Palau. His work focuses on testing and growing the number of heat-resistant corals. (Photo: Dan Griffin)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Record-breaking heat in the oceans is disrupting marine ecosystems around the world in a multitude of ways, including the most widespread coral bleaching event ever documented. The Coral Reef Watch at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA tracks coral bleaching and confirmed that the current global bleaching event, which started in January 2023, has impacted almost 84% of the world’s coral reefs. Coral bleaching happens when ocean temperatures are so hot that the stressed-out corals evict their symbiotic algae, turning the corals white and making them look “bleached.” This weakens the corals and many end up dying. But others can recover and even thrive amid hotter oceans. Stanford University Professor of Biology and Oceans Steve Palumbi has been working to find ways to help corals given the extreme heat that now seems commonplace in our world.

PALUMBI: Remember the Taylor Swift song, "Cruel Summer”? Well, we've had two “cruel summers,” 23, 24 you know, what are we going to see in 25? We don't know, but that report from NOAA is a sort of clarion call that “cruel summers” are happening more and more frequently, and it's affecting these corals.

O'NEILL: So apart from the climate crisis, what other factors pose a threat to coral reefs?

PALUMBI: Even before we were really worried about heat waves, corals were suffering from a lot of different other kinds of things. Overfishing causes corals to die. Why? We're not eating the corals. We're eating the fish. The fish play a big role in keeping the coral reef clean, eating algae that overgrows the coral, and so overfishing causes a lot of coral death. Pollution causes coral death, development causes coral death, dynamite fishing. So there's a whole series of things that are typically called local stressors that cause corals to die. And Aynsley, as a consequence of these other things hurting corals, when we're talking about protecting them, restoring them, bringing them back, climate and fixing that is a huge, huge part of it, but it is not the only part. And so actually solving the local stressors and the global stressors is something that always has to go hand in hand.

O'NEILL: Now so we last spoke to you about coral bleaching back in 2013 over a decade ago. How has the situation changed since then? What have we learned about corals in the last decade?

PALUMBI: Well, you know, Aynsley, we've learned a huge amount about corals in the last decade, particularly about bleaching. The tools that we have now available to study bleaching, to look at the genetics, the genomics of it, the physiology, the consequences, the mapping where it happens, satellite tools all the way down to intracellular kinds of probes added enormously to what we know about coral bleaching. But you know, the thing that really strikes me as being the most important is that not all corals are as heat sensitive as others. There are some out there that are pretty heat resistant.

O'NEILL: And so a heat resistant coral, meaning it isn't as affected by these rising temperatures, then?

PALUMBI: Right, I mean, they're not affected the same way in the heat wave. And you can see that in a picture of a bleached coral reef, your eye immediately goes to the white patches, because those are the bleached ones. But my eye goes to the not white patches. My eye goes to the corals that have not bleached. And those have really gone from this incredible mystery over the last decade — How can that happen? — to an incredible asset because we know they're there, and now we're learning more and more about how to use them.

O'NEILL: And as I understand it, there's this sort of potential, and this sort of project about creating even more heat resistant corals. Tell me a little bit about that.

PALUMBI: There's a lot of attention in the coral sort of research and management community about interventions in coral reefs to help them become more heat resistant. And there's a wide set of different tools. You can expose them to a little more warmth, paradoxically, heat them up a little bit, and they get more heat resistant because they get used to that, that warmer temperature, they acclimate. You can maybe swap out the symbionts for a more heat resistant one. People have experimented in putting on pastes of different microbes that might allow them to become more heat resistant. We already know that one of the most important things about that heat resistance is that we don't have to make it all because it's already there. If you use simple tools to go out and just measure the heat resistance of corals, you can find some that are much more heat resistant than others. And then sometimes there are different species. This species is much more heat resistant than this other species. Sometimes it's a different colony in the same species that's much more heat resistant than a colony of the same species from the same place.

O'NEILL: So what would you say is the status of some of these projects? How widespread is the interest in creating heat resistant corals around the world?

PALUMBI: There's a huge interest in creating or finding heat resistant corals around the world. There's efforts, for example, of finding heat resistant corals and using them to set up marine protected areas where there's a lot of them. You can find heat resistant corals and then place them in restoration sites. And so we've been doing a lot of that. We've created a training program called the Coral Futures Academy, led by Courtney Klepac, and that's to train people to do this all around the world. Other people are taking those same corals and breeding them together to try to, like, get the next generation of extra heat resistant ones going at the same time. There's also attempts to try even beginning of genetic engineering to make them along the way. And so all of this set of work, from finding them to breeding them to using them, is all a set of people trying to do the same thing in different ways, which is a great way to try to solve a huge crisis.

O'NEILL: And now I understand that coral reefs actually make up something like less than 1% of the world's ocean, so some might then go, "Well, why are they so important? They're pretty, sure, but why are we working so hard on this?" What would you say in response to that?

PALUMBI: Yeah, the people that live on coral reefs don't say that. And the people who live on coral reefs say, "Can I get my corals back, please?" It's not because they care that much about the corals. I mean, they do. What they want is the fish and corals and coral reefs and coral reef fish are tightly tuned to one another, and for a group of people that uses local reefs as a fishing location for the food for them and their family, their kids, for commerce. They need that in order to survive. Hundreds of millions of people rely on that source of food. They also have this tendency to make rocks. They make rocks in front of the waves, in front of your village or your hotel or your river or your bridge, and so they're like living sea walls that are constantly growing to protect the shoreline. And all these things, food and protection from storms mean that they're hugely valuable as ecosystems to people.

O'NEILL: Now, Steve, let's take this from a climate perspective. You know, even if humanity were to stop releasing all greenhouse gasses tomorrow, global temperatures would keep rising, at least for a little while. So how much of a difference would it mean to coral reefs to cut greenhouse gas emissions sooner rather than later?

PALUMBI: You know, that is an incredibly important question about what it is we're trying to do, because you're totally right, if we stop putting more CO two in the atmosphere today, or in five years, or even by 2050, it's still going to get warmer. The climate crisis is still going to get worse, but eventually it's going to stop and start to get better. And I refer to that as the stopping distance. You know if you're in a car and you're driving along, and you put your foot on the brake, your car is not stopping instantly. It takes a while to bring it to a halt, and so you have to give yourself a space between your car and the car in front, not necessarily in Boston, because I know how you all drive, but in other places, there's this space that you provide. That stopping distance is what we're dealing with now. We have a stopping distance for stopping climate change, but you still got to put on the brakes. You still have to stop. You still have to get that car, get that process to stop, or you'll just run right in to the car in front of you. And that's what we're talking about for reducing CO2 emissions, is putting on the brakes and bringing things to a stop. Now the other part of the question is, all right, how long is that going to take? And then how is what you're doing now going to affect that? And yeah, we have to stop climate change. We have to stop the emissions. But that's not enough because if we did just that and we fixed climate change and the world is dead, we weren't successful. So we have to stop climate change with enough of the world there to be able to grow back from this problem. And that's what we're talking about, saving coral reefs enough now and into the future, so that when we fix the problem, there are coral reefs to grow back.

O'NEILL: Now, solving the climate crisis is obviously a big project, and that's just one aspect of this, though. So what else can be done to save coral reefs on a general level?

PALUMBI: You know, to protect reefs on a general level is really protecting them on a very place based very specific level. What does the reef right here in front of this village need? And what we found going around the world and talking to people about testing heat resistant corals is that people want their reefs to thrive and to be healthy, whether that's for the tourists they bring in or for the fish they bring in, or the protection or the livelihoods or whatever. It's a really amazing natural part of their world, and so helping give them the power to do that is something that, I think is another real aspect of this. We've made the equipment to test corals for heat resistance much cheaper than before. It's just a couple $100, it works in very low infrastructure places you need some power and access to water, but you don't need a marine mab. And we can turn that over to local people doing it. If we can get them jobs to manage reefs with these tools, then they'll begin to build these reefs. And once you start building a reef with heat resistant corals, you're much more dedicated to its survival. And so we're seeing the building of local systems to help these reefs. So lots of the coral world, it's a village-based solution that's really going to work.

O'NEILL: Well, there's a lot of what ifs when we talk about this question. But how optimistic do you feel about the future of coral reefs at this point in time?

PALUMBI: I'm feeling pretty optimistic about it, mostly because I think that as we get closer and closer to 2050, and we have many other ways of energizing our industry and homes besides burning fossil fuels. Do you really want to put $100 worth of gasoline in your car every week, or every two weeks, you know? Or would you rather not? So I think those kind of considerations will really help us, not that it isn't going to be a lot of work, but there's people working on it too. And then I look out on the reefs, and some of them are really in dire shape, like the reefs in Florida, a lot of the ones in the Caribbean, but a lot of them are not yet there. There's diversity, there's fish abundance, there's vibrant growth. If you look in those reefs, there are corals there that are much more heat resistant than others, and so these tools we never had available before, being able to find heat resistant corals, be able to identify them, be able to grow them out, be able to have them create new reefs, are things that we never could do before. And it's not going to solve the problem, but it will certainly help, and it'll get us the next 10 or 20 years, where then we might have corals that are bred for more heat resistance, and they'll be able to go online and etc, etc. So I think we're on a path. I'm encouraged about that, and we've never been on this path before, and so that's what gives me hope.

O'NEILL: Dr. Steve Palumbi is a professor of biology and oceans at Stanford University. Thank you so much for taking the time with us to us today, Steve.

PALUMBI: Hey, Aynsley, this was such a pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn about one of Dr. Steve Palumbi’s projects in the Marshall Islands

- Read the NOAA report about coral bleaching

- Explore more of Steve Palumbi’s work

- Listen to Steve Palumbi’s climate-focused parody of Taylor Swift’s “Cruel Summer”

[MUSIC: Flying Fingers, "Cruel Summer," by Annie Clark, Jack Antonoff, Taylor Swift, on 20s Piano Pop Covers (Vol. 5), produced by Mikael Bäck, 2023]

O’NEILL: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You'll never miss a show, and you'll have special access to show highlights, notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live virtual events. The Living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don't miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe.org, that's loe.org. And by the way, you'll also find photos, links to more information and a full transcript of every single show there. And we'd love to hear from you. You can write to us anytime at comments@loe.org, That's comments@loe.org.

[MUSIC: Flying Fingers, "Cruel Summer," by Annie Clark, Jack Antonoff, Taylor Swift, on 20s Piano Pop Covers (Vol. 5), produced by Mikael Bäck, 2023]

O’NEILL: Coming up, California farmworkers are exposed to unhealthy levels of pollutants, particularly from wildfire smoke. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ellie Johnson Trio, “Street of Dreams” on Street of Dreams, Ellie Johnson Trio]

Protecting Farmworkers from Wildfire Smoke

Farmworkers in California are exposed to dangerous levels of particulate matter in the air, and a 2024 study shows that even levels of pollution deemed ‘safe’ by CAL-OSHA can be hazardous to human health. The farmworker shown here is Adriana, whose name has been changed to protect her identity. (Photo: Courtesy of Rambo Talabong)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Recent days have seen heavy smoke from Canadian wildfires spread into parts of the U.S. as climate change drives more extreme fire seasons. And when it comes to the health and safety of people who grow the food we eat, the poor air quality from that smoke and other pollutants is a top concern. A 2024 study found that current air quality thresholds for some of the smallest particulate matter, known as PM2.5, may leave California agricultural workers dangerously exposed. And this pollution can affect the body in more ways than just the cardiovascular system. The California Division of Occupational Safety and Health or CAL-OSHA sets an air quality threshold for what’s considered "safe" for outdoor workers. But UC Davis economists found that even when air pollution is below that limit, wildfire smoke can increase the risk of farmworkers sustaining injuries like falls and cuts on the job. The study linked workers’ compensation injury claims with wildfire activity across California from 2007 to 2021, estimating at least 282 smoke-related injuries in 2020 alone. Reporter Rambo Talabong covered this research for our media partner Inside Climate News, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: What are the PM2.5 thresholds in California, and how do they compare to you know what the researchers in this study recommend?

TALABONG: According to California, our farm workers need to be exposed to 150 AQI that's very high before employers need to protect them and give out face masks, according to researchers of air pollution, even before we hit that threshold, it can be dangerous, and there are also complicating factors here, because farm workers are outside for long periods of time, they're exposed to more pollution. So it's not just a matter of reaching that threshold, but also protecting them even before that threshold is hit. And in California, the researchers found that our farm workers are not protected enough. That's why we also hear a lot of stories where farm workers are saying it's already smoky outside, but we haven't received any single face masks. Our employers are not letting us go home or do flexible time for working to protect ourselves and work another day. So that's how it plays out on the ground.

BELTRAN: What sorts of protections does the state of California require for farm workers when it comes to fires and air pollution? And who's responsible for enforcing those protections?

Adriana often works on a strawberry farm. She has been farming for over twenty years. (Photo: Courtesy of Rambo Talabong)

TALABONG: For California it's Cal/OSHA, and under Cal/OSHA's rules, employers would have to give out at the very least face masks to farm workers when the AQI reaches AQI 150. Again, that's quite high, according to researchers. And compare that to a state like Washington state, their threshold is at around 70. That's around half of what California's is. And according to researchers, giving out face masks actually is not enough. What California needs to do, and what employers need to do in California is to make work days flexible for our farm workers, to give them the opportunity to not work one day and then do extra work in different days so that they can earn back what they have lost in not working. And this is also fair for farmers. For the owner of the farms, they still get productivity from farm workers. It's not a free pass for farm workers, okay, it's a pollution day. They don't have to work, but they still get the money that they deserve. We spoke with farmers, and they also believe that it's fair that farm workers can be granted these extra days of work and hours of work. And what struck me, in the states of Washington, they give a lot of talks to farm workers and farmers about the dangers of higher air pollution, and so that means that they're more informed about the harms that they have when it comes to days when the pollution is bad, and they can decide, okay, I'm probably not going to work today.

BELTRAN: And we're talking about PM2.5 here, this pollutant. What are some of the negative health impacts of exposure to PM2.5?

TALABONG: According to researchers we spoke with about the effect of PM2.5 for heart and lung diseases that are linked to constant exposure to PM2.5, but then what's interesting also with this research paper is that it didn't just focus on long term effects. It's also about immediate effects. We already feel bad or worse when we get exposed to PM2.5 and pollution, even not in the long term, it can happen immediately, and this happens to farm workers. When we are exposed to pollution, our hand-eye coordination and our locomotive coordination is actually impaired because our brains are already impacted by bad air, and agricultural workers are already a very vulnerable population to injuries. They're among the most dangerous professions in the US, and if there is pollution outside, it makes them more vulnerable to hurting themselves, tripping, cutting themselves while harvesting, they might fall. And these are things that the researchers recorded, and this is actually what researchers are also worried about, that while farm workers are outside, they can end up hurting themselves because of pollution.

The study notes that high levels of wildfire smoke correlate with high risk of traumatic injuries for farmworkers, such as those from falls. Researchers focused on traumatic injuries in the workplace, as they are easier to prove a connection with workplace conditions as opposed to non-traumatic illnesses like heart and lung disease. (Photo: Courtesy of Rambo Talabong)

BELTRAN: And for your reporting, you talked to Adriana, whom you changed her name to protect her anonymity. What's her story?

TALABONG: So Adriana moved to the US at a very young age, and for her, it's a matter of having to work or else she wouldn't have money to pay the bills in order to stay in the US and even thrive in her community. And so this in practice shows in how when there are wildfire days, she would force herself to work, and it's harder also for her to leave, because if she doesn't work, and if her fellow coworkers don't work, she wouldn't be able to earn and so it's such a precarious situation wherein she's already exposed to pollution, but she also doesn't want to face, you know, financial insecurity and ruin. She needs the money. And also, sometimes her bosses would essentially tell her, you have to work or you wouldn't be able to come back, because you're essentially expendable.

BELTRAN: And of course, Adriana is one of the many farm workers who is exposed to this dangerous PM2.5 levels. How has her health been impacted throughout the years of her farm working?

TALABONG: Well, first of all, she told me up front that she's recently experiencing a lot of coughs, and she even told me about seeing blood after coughing. And so that's quite worrying that she is experiencing this. But she was also telling me it's hard to prove that to get claims, because the system helps people who immediately have injuries. You see this with contusions, with cuts. You can see them in pain, but with cardiopulmonary and cognitive impacts of pollution, it's harder to prove that it's actually the pollution from working in the field that brought you to that situation. And so when it comes to her working, there are times when she told me that she has fallen because of the blurring the field. But also not just with wildfires. The thing about this too, is that it compounds. You know, there is wildfires, and then sometimes it's also rains, and then it's so hot, too. She's fallen a lot of times. And what's hard here Paloma, is that we can't really draw a line as easy as okay, because it is a bad wildfire day, and so she will fall. It's hard for her, and it's hard for us, and it's hard for researchers, and so we're stuck in this problem of they get injured, and we know that in many of those days, it might be wildfire days or high pollution days, but we can't be sure. That's why I think this research is very important, is because they use modeling.

Rambo Talabong is a New York-based journalist who writes for Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Rambo Talabong)

BELTRAN: And how do UC Davis researchers hope that their most recent work will impact protections or change protections for farm workers?

TALABONG: The researchers I spoke with have a background in agricultural economics, so they aren't just outright advocating for these lower the thresholds as much as we can, because they also understand how it might be harder for farmers to comply. The researchers are telling me that we could just gradually decrease the threshold to match other states. And that can actually be helpful for the industry as well, so that when they comply, they can comply with all states, 150 right now for California, around 70 for Washington State. So lowering California's can help farmers too in the industry in complying. Aside from that, they really emphasize that flexible work times can help. This is also fair for the farmers, because even if farm workers don't work one day, the economic output that they expect to have that day can be earned back. They're not saying, Okay, we need the strictest standards as much as possible, because they also understand that if these standards become too strict, farmers wouldn't have enough incentive to employ more farm workers, and that means losing jobs for people like Adriana. It's a matter of informing as many people as possible about what we can do to protect our farm workers.

DOERING: That’s Rambo Talabong, a reporter with Inside Climate News who focuses on environmental justice, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. We reached out to Cal/OSHA and they did not meet our response deadline but they did point us to a section on Worker Safety and Health In Wildfire Regions on the Cal/OSHA website. There you can find the guidelines for employers to protect workers exposed to wildfire smoke, and we’ll link to it on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “In California, Flawed Air Rules Threaten Farmworkers as Wildfires Pump More Smoke Onto Fields”

- Read the study from agricultural economists at University of California Davis

- Learn more about the intersection of air quality and farmworker safety

- The Guardian | “Canadian Wildfires Prompt Air-Quality Alerts Across Five US States”

- More on worker safety from Cal/OSHA

[MUSIC: Ellie Johnson Trio, “Volare” on Street of Dreams, Ellie Johnson Trio]

Keeping the Vjosa River Wild

2025 Goldman Prize winners Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika. In 2014, they publicly launched the “Save the Blue Heart of Europe” campaign to protect the Vjosa River from a hydropower dam development boom. Their activism resulted in its historic designation as the Vjosa Wild River National Park by the Albanian government in March 2023. This safeguards the Vjosa, which flows freely 167 miles from the Pindus mountains to the Adriatic Sea, and also its free-flowing tributaries. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: While countries like the United States are seeking energy independence by expanding oil and gas production, the small Balkan country of Albania is following a more fossil-fuel-free approach. The country already produces ninety nine percent of its energy from hydro-power and it has plans to become a major exporter of hydro by building as many as three thousand dams. But that clean energy can come at a cost to freshwater ecosystems by blocking fish migration and turning wild rivers into sluggish reservoirs. One of the last remaining free-flowing rivers in Europe is the Vjosa, which runs one hundred and sixty-seven miles from the Pindus Mountains in Greece through Albania to the Adriatic Sea. 2025 Goldman Environmental Prize winners for Europe, Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika, recognized the Vjosa as a biodiverse jewel worth protecting. So they led a group of campaigners who successfully fought to keep the Vjosa from being dammed for hydropower. And in March 2023, the government of Albania designated the Vjosa Wild River National Park, protecting both the river itself as well as its vital tributaries. Besi told me the park is a national treasure.

GURI: There's so many activities that you can do in the river. And what's also very important outside the river, there is plenty of activities, but the river itself gives you, you know, time to relax with your family or with your friends. You can swim there, you can do rafting, or you can walk along the river. And the river itself is very reachable, even by bus or by car, by bike. So it's really accessible. But what's also important is that the whole valley is very interesting. The cities along the Vjosa are really nice and cute cities. You also have World Heritage cities like Gjirokastër, for instance, and the delta of the Vjosa, where you can do bird watching. You can watch the flamingos there and the pelicans. It's really, it's a mosaic of natural beauty.

2025 Goldman Prize winner Besjana (Besi) Guri, 37, was trained as a social worker and has always had a strong connection with nature. Besi, whose expertise is communications, has worked closely with Olsi at the NGO, EcoAlbania, on the campaign to stop the Albanian government from building hydro dams on the Vjosa. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: So what was the government of Albania weighing, in terms of, you know, the pros of making this designation to protect the Vjosa River and create this Wild River National Park, versus what was, on the other hand, that they were balancing and trying to weigh? How hard was it for them to make this decision?

GURI: Well, since when we started the campaign, there were plans to develop hydropower, to build hydropower projects in the Vjosa, we started our fight, fighting a single one, one project, the Kalivaç Hydropower. That was already a concession. That was a big dam. The work had started, but luckily stopped some years before we publicly started to fight. But on the way, we learned that there were eight in the main river and thirty-something more in the tributary, so a total of 45 hydropower. So our government definitely had big plans for hydro energy in the Vjosa, and it wasn't really easy for them to change course. And also for us, it was really hard to make them change the course. I'm bringing here to attention that in that time that we were starting, we're speaking about 2012-13, Albania had this vision to develop the hydro and to be also a superpower in the Balkans for energy production. So everything looked like it's a good thing, you know, it's a green energy, and we want to develop the country and so on. And even the people, they didn't really understand what is so bad about the hydropower and why we should protect nature and why we should have the Vjosa free flowing. So it wasn't really easy to convince them. We found our ways, but it was a long way, of course.

Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika look out over the Vjosa River, which is fed by 250 miles of tributaries. As part of the Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign, the two argued that dams would irreversibly damage the ecology of the Vjosa river system. (Photo: Adrian Guri for the Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: They must be a testament to the effort that you put in to building a grassroots movement here. You know, working with the local communities and really communicating with the government about the benefits of protecting this. I mean, you know, a lot of the time when there are business interests, development interests, up against environmental preservation interests, the business interests often win out. What do you think helped you succeed?

GURI: Our vision was stop the dams, declare a national park. So that's how we started everything, but that was really a vision at that time, and sometimes it even felt like really not very possible to achieve. But we stick to the plan, and throughout the whole time, we managed to bring in scientific arguments why the Vjosa is so unique and why it should be protected, and we try to convince our government that they should first study the river, assess what they have, and then take decision for the fate of the river. Because when you lose it, you lose it forever. When you interrupt the free flowing river and you put a dam in it, then it's gone. The vision for a Wild River National Park is gone. We built a multi tool campaign, I would say, and we also made our government's life impossible, because everywhere they would go, they would hear about the Vjosa. “National Park” sometimes to people is translated to restrictions. But in the Vjosa case, we had a supportive community that were on the front line with us, or we were on the front line with them, and they understood that a national park would bring them much more possibilities than the hydropower, and they saw the threat is there, so they were really strong, having petitions, having protests, being in court cases with us. We won first environmental court case in Albania for Vjosa. As a country, Albania had no precedent of environmental cases in the court, and the Vjosa was the first one, and opened the way for many other cases.

The village of Kutë sits alongside the Vjosa River in southeastern Albania. Residents in the small rural community depend on the waterway for farming, fishing and tourism. (Photo: Adrian Guri for the Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: Albania does generate 99% of its electricity from hydroelectric power. That's a renewable resource. It doesn't involve burning fossil fuels, but there are ecological impacts from dams. Talk to us about the delicate balance there between humanity's need for clean energy while preserving wild nature.

GURI: It's weird because we as a country, we have 300 and something days of sun, so almost all year we have a lot of sun, and Albania could use that. We also have potential for wind power, and that's one of the arguments that we've been using with our government. Why do we want to exploit all the rivers? Why do you want to destroy all the rivers? Well, you can use alternatives, and that's what, what I think that is the best. We need to change our habits, on the way we live and on the way how we use energy, but we need to find the balance and to use different alternatives, because even depending on hydro is not that sustainable at all. For instance, in the dry season, Albania still imports energy. So when you have a lot of production, you export it. In the end, it's about business. It's not about energy. That's the problem.

Pocem, Albania, sits along the Vjosa as it winds 167 miles from the Pindus mountains in Greece to the Adriatic Sea. Pocem is known for its agriculture and historical sites. Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaigners argued that damming the river would destroy the rich biodiversity of the Vjosa and its tributaries. (Photo: Adrian Guri for the Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: A lot of people involved in making this possible, but of course, you and your co-recipient, Olsie Nika, are the Goldman Environmental Prize recipients for Europe in 2025. How does it feel to be a Goldman prize winner? And what does the award mean to you?

GURI: I'm very honored, and so so happy to have been acknowledged with the prize. It's really something special for me. But what it's really makes me think that even when you don't think that people are watching you, you know, it's important that you do what you do with the passion, and there will come a moment that others will see what you're doing.

2025 Goldman Prize winners Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika at a sign designating the Vjosa Wild River National Park (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: Besjana Guri and her colleague Olsi Nika are the 2025 co-recipients of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Europe. Thank you so much, Besi, it's been such a pleasure.

GURI: Thank you for having me. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more from the Goldman Prize website

- Balkan Insight | “Fight to Protect Albania’s ‘Wild River’ Isn’t Over, Say Environmental Prize-Winners”

- Balkan Rivers | “2025 Goldman Environmental Prize for EcoAlbania's Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika”

- Gear Junkie | “Save the Vjosa River: Albanians Fight Damming & Diversion in Patagonia Short Film”

- Goldman Environmental Prize’s Video on Besjana Guri and Olsi Nika

- EcoAlbania | “Vjosa: A Global Inspiration — Albanian Activists Honored with the Green Nobel Prize!”

[MUSIC: Govi, “Espresso” on Touch of Light, Govi Music]

Listening on Earth

Living on Earth Producer Sophia Pandelidis walks through the streets of the Greek island, Paros. (Photo: Stephanie Morris)

[CHURCH BELLS]

O’NEILL: This week’s Listening on Earth comes from Albania’s neighbor, Greece, and was recorded by one of our colleagues.

PANDELIDIS: This is Sophia Pandelidis, producer here at Living on Earth, and those were the church bells that woke me up on Sunday morning in Paros, Greece.

O’NEILL: Sophia’s living the ultimate dream of remote work life for the next several months!

[BOUZOUKI MUSIC]

O’NEILL: She also sent along a taste of festive bouzouki music in a café, again on the island of Paros, which is in the Aegean Sea between Santorini and Mykonos.

[BOUZOUKI MUSIC]

A church in Paros, Greece. (Photo: Stephanie Morris)

O’NEILL: To join Sophia and other listeners, please send us your sounds by using any sound recording app on your phone, like Voice Memos or Voice Recorder. And for the best audio quality make sure to stand still for at least two minutes without fidgeting or talking. But of course we do want to hear from you! So be sure to speak clearly and let us know who you are, where you are, what you’re hearing and what inspired you to record the moment. Then you can email the file to comments@loe.org, and we might just use your audio postcard on the air! That’s comments@loe.org.

Related links:

- How to make a sound recording on an iPhone

- How to make a sound recording on an Android

[MUSIC: Paraskevas Grekis, “Mes Stou Egou” on Greek Islands Music on the Bouzouki, Arcade Music Paris]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, cut for half hour only Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth