May 2, 2025

Air Date: May 2, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Air Gets Worse

View the page for this story

The latest “State of the Air” report by the American Lung Association finds air quality has worsened so much that nearly half of people living in the U.S. now breathe unhealthy levels of air pollution. Soot and smog are on the rise in part because climate change heat is bringing more wildfires and low-level ozone-forming conditions. David Cash was the New England Administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency under President Biden, and he joins Host Jenni Doering for an air quality update. (09:22)

NOAA Climate Science Cuts

/ Abrahm LustgartenView the page for this story

A key climate modeling program within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA is slated for near-elimination, according to a draft White House memo. Abrahm Lustgarten investigated these planned cuts for ProPublica and discusses with Host Jenni Doering the potential impacts to weather forecasting, disaster preparedness, agriculture, military operations and more. (11:45)

Tariffs and Green Energy Cuts

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration’s on-again, off-again tariffs and cuts to renewable energy programs are bringing instability and uncertainty to the future of US energy. Collin Rees of Oil Change International talks with Host Paloma Beltran about how the trade turmoil and policy whiplash are impacting and sidelining the U.S. renewable energy industry. (10:09)

Parrot Brains and Our Own

View the page for this story

Parakeets have astounding vocal abilities and are able to mimic as many as 1700 human words. And their brains may provide insight into how we humans talk. In a recent study, researchers found human-like neural activity during vocalization. Dr. Michael Long led the study and joins Host Paloma Beltran to share how this research may help shed light on communication disorders in humans such as autism. (13:39)

Listener Postcards

View the page for this story

We asked you, our listeners, to submit snippets of the sounds around you. Here are a couple more of your submissions. (01:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250502 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: David Cash, Michael Long, Abrahm Lustgarten, Collin Rees

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The Trump administration proposes huge cuts to weather and climate modeling.

LUSTGARDEN: If we don't have an accurate forecast, we’ll be blindsided by the storms that will inevitably come, and the less warning we have, the greater the impact, and the greater, you know, the destruction and the danger to the people that live in the places that they strike will be.

DOERING: Also, studying parrots might help unlock how the human brain allows us to speak.

LONG: There are brain cells in the parrot's brain that are active when the bird speaks sounds that are consonant-like, others that are active during vowel sounds, others that are active during high and low tones. And we do see something that looks just like this in the human brain.

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Air Gets Worse

The 2025 California Palisades Fire, pictured above. Fires significantly contribute to both air pollution and climate change by releasing pollutants and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. (Photo: Cal Fire, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The latest “State of the Air” report by the American Lung Association finds that nearly half of people living in the U.S. breathe unhealthy levels of air pollution. The report examined air quality data from 2021-2023, during the Biden administration, and found that 156 million people are living in areas that received an “F” grade for either ozone or particulate pollution. That’s 25 million more people than in last year’s report.

BELTRAN: Exposure to ozone and particulate pollution, or “smog and soot” is linked to serious health impacts including heart attacks and strokes, preterm birth, and impaired cognitive functioning later in life. The American Lung Association says a person of color is two times more likely to live in a neighborhood with unhealthy levels of toxic air pollutants. And Latinos are nearly three times as likely to live in an area with failing air quality grades.

DOERING: David Cash was the New England Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under President Biden. And he’s grown increasingly concerned about how the Trump administration is dramatically reshaping the agency. David joined me to talk about this recent report and what in his view the federal government should do to protect Americans from unhealthy air.

CASH: You have to remember that when we first started getting the ball rolling seriously on air pollution was in the 1970s under a Republican administration, Richard Nixon, and when we put the Clean Air Act into place and the idea of that was for the federal government to regulate Cars and factories and power plants, such that our air would get cleaner and cleaner and cleaner over time, which it has. Some estimates are that 80% of soot and smog has been addressed over that time. There are still major pockets of air pollution throughout the country, mostly in industrial and urban areas, and that covers upwards of 140, 150 million people who are in these areas. And it's the responsibility of every administration to keep on figuring out how to reduce air pollution while we still maintain economic development and innovation. And every administration has done that, some better than others. In the last administration, the Biden administration in which I worked, we ratcheted down some regulations in such a way that we would continue to get the benefits of cleaner and cleaner air, and those benefits are huge, in the billions and billions of dollars every year in avoided health care costs and things like that. What we've seen the Trump administration announce is its plans to roll back those kinds of regulations.

DOERING: I think one of the things that was maybe surprising for people looking at this American Lung Association report is just seeing that air quality actually decreased from the previous year. Why is that? What's going on?

Donald Trump’s crusade against offshore wind just got more serious

— The Verge (@theverge.com) April 17, 2025 at 11:10 AM

[image or embed]

CASH: Yeah, there are a couple of reasons, and they can go back to climate change as driving those changes, because we have been slowly but surely cleaning up our cars and our power plants, things that come out of smokestacks. We have had a couple of events in the last year that really drove local air pollution. And you might have heard of the wildfires that were in Canada, wildfires out west, even wildfires on the east coast in the state that I'm in Massachusetts, had wildfires last summer unlike any we've experienced, and all of that contributes to poor air quality. You may recall the photographs that were seen over both cities and rural areas that just showed this orange kind of haze in the distance. What that haze is made up of are particles, and those particles, when you breathe them in, can make you sick. So, that was the primary driver. And by the way, the reason I said climate change is those wildfires, the intensity of those wildfires, the probability that we have those wildfires, increases because of climate change. The second piece is that climate change is resulting in warmer and warmer days, and when you have higher and higher temperatures, that soup of smog and other industrial chemicals combines in the hotter weather to form air pollution that causes these problems. So climate change is driving both wildfires that are dirtying the air and heat increases that result in greater air pollution at ground level.

DOERING: And just how many people are living with this unhealthy air according to the American Lung Association?

David Cash (bottom right), along with students living in Worcester, Massachusetts at an event celebrating the city’s new electric school bus. According to the Greater Worcester Community Foundation, about 12% of school-age children had asthma in 2018. (Photo: David Cash)

CASH: So the American Lung Association report shows that about 150 million, slightly less than half of the population of the United States, live in areas that experience these high levels of air pollution, and you won't be surprised to understand that Black and brown communities experience these high levels of pollution at greater rates than the general population. Low income communities, Black and brown communities, those who are in industrial centers, who are near manufacturing facilities, who are in transportation corridors, all experience these high levels of pollution at a much greater rate than the general populous does.

DOERING: Now what makes soot and smog so dangerous?

CASH: So there are a couple of different health impacts, and one of the most persistent and dangerous are really, really tiny particulates that come from industrial pollution, or that come from wildfires, and when you breathe them in they lodge in your lungs and the result is increased asthma attacks. The long-term effects can be heart disease, can be various lung ailments. So there are a lot of problems that can result from these. And then there are a whole host of kind of toxic air pollutants that can result in long term, can result in things like cancer.

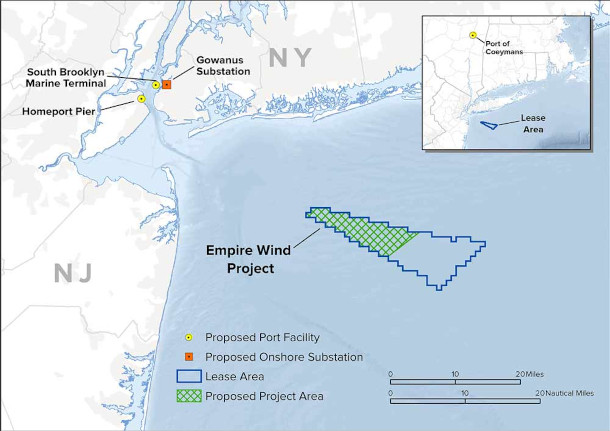

Map of the Empire Wind lease area (blue outline) south of Long Island, with the proposed project area (green) and planned transmission route to Brooklyn. The Empire Wind Project owned by Norway’s state energy company Equinor was ordered to stop construction by the Trump Administration. (Photo: NYSERDA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: And some of these particles from industrial pollution and wildfires are so small they can even, like, make their way into our blood vessels.

CASH: Yeah, no, that's right, they're tiny, tiny, and that's why they're so dangerous because it can really get in deep, deep into your lungs and then get into your blood.

DOERING: Now, what role does the EPA play in enforcing air quality standards and regulations?

CASH: Historically it's always played a very protective role. That's the job, the Environmental Protection Agency, designed to protect your health, my health, everybody's health, and the ecosystems upon which we depend. And there are a whole set of different regulations that EPA has done based on laws that Congress has passed, like the Clean Air Act, and working with the states, we enforce those. So, EPA, if they discover a power plant that's emitting too much, it will take enforcement actions to shut it down or require a fine or require new kinds of technologies. So there are a lot of different ways that EPA works to make sure that our air is clean and it's all based on science. It's all based on the science of the atmosphere, the science of gases, the science of our health, which is another pillar of protection that's being heavily eroded by the Trump Administration, as they are firing scientists, limiting scientific advisory committees, ignoring reports that are being done, stopping reports from being done like about climate change. So, there's a whole host of ways that the Trump Administration is taking actions that will make our air dirtier, that will cause more health problems, that won't address climate change, and that will give up opportunities of clean energy development.

David Cash is the former Administrator of EPA's Region 1, New England. (Photo: Courtesy of the EPA)

DOERING: And before you go, how do we get back to those bipartisan days when environmental protection was something that you know both major parties in the U.S. care about?

CASH: I think that we have to make sure that we uplift the voices and stories that are central to this experience right now. So those who are experiencing increases in trips to the emergency room with their kids who have asthma attacks, for those who had a great paying job on an offshore wind project and just lost their job, for a factory, a battery factory in Kentucky, that's going to close because the administration is halting electric vehicle policy. I think those are the stories that are going to resonate with policy makers. Moving into the clean energy future has so many benefits, all across the political spectrum for so many different sectors, for so many different kinds of jobs, it will improve people's lives. And we have to tell that story in a way that will convince politicians, regardless of whether they're in a red district or a blue district, that this makes sense.

DOERING: David Cash is the former administrator of the New England region of the U.S. EPA, thank you so much David.

CASH: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- American Lung Association | “New Report: Nearly Half of People in U.S. Exposed to Dangerous Air Pollution Levels”

- E&E by Politico | “Democrats Grill Top Interior Nominee on Empire Wind”

- The Guardian | “Nearly Half of Americans Breathing In Unsafe Levels of Air Pollutants – Report”

[MUSIC: Bryan Sutton, “Shady Grove” on Appalachian Picking Society, BMG Music]

BELTRAN: Unhealthy air affects everyone, but especially the environmental justice communities that are exposed to the highest levels of air pollution. And for our next Living on Earth Book Club event on May 8th we’ll talk with Catherine Coleman Flowers about fighting for vulnerable communities who have been denied the basic right to a clean and healthy environment. Her new collection of essays, Holy Ground: On Activism, Environmental Justice, and Finding Hope, weaves together the personal and political to reflect on EJ of the past and the future. Don’t miss Host Steve Curwood’s live virtual conversation with Catherine Coleman Flowers, on Thursday May 8th at 8 PM Eastern! Register at loe.org/events. That’s loe dot org slash events.

[MUSIC: Bryan Sutton, “Shady Grove” on Appalachian Picking Society, BMG Music]

DOERING: Just ahead, parts of the fossil fuel sector got an exemption from President Trump’s tariffs. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bryan Sutton, “Shady Grove” on Appalachian Picking Society, BMG Music]

NOAA Climate Science Cuts

Experts worry that funding cuts to NOAA will undermine our ability to predict hurricanes, leading to more lives lost. (Photo: Dannel Malloy, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

It is not an easy time to be a climate scientist. The Trump administration is slashing research funds. And on April 28th hundreds of scientists were dismissed from their work on the National Climate Assessment due in 2028. Every four to five years this report projects domestic climate impacts to help guide decisions about preparing for rising seas, extreme heat, stronger hurricanes and more. It is unclear how the Trump Administration plans to complete the sixth assessment, which is required by Congress. And the climate modeling that underpins reports like the National Climate Assessment is itself a target of the Trump Administration. Here to speak to us about proposed cuts to climate research at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is journalist Abrahm Lustgarten. Hi Abrahm, Welcome back to Living on Earth!

LUSTGARTEN: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So, you wrote an article for ProPublica about federal funding cuts to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. What is the extent of these cuts?

LUSTGARTEN: The proposed cuts for NOAA, which come from a leaked document from the Office of Management and Budget, essentially proposed to decimate the agency as we know it. They're not total, they would preserve certain functions. They say that they want to prioritize and preserve the National Weather Service and the kind of weather forecasts that we're all used to getting, for example. And there are other programs within NOAA that will survive or struggle on, but the Office of Atmospheric Research, which is NOAA's primary science division that focuses on climate change, especially is slated for about 74% cuts, and the memo describes that as basically the elimination of that office of the agency, even though there's some funding left. And overall, the agency would face about 27% cut. It would lose a couple billion dollars, and this will affect everything from the data that it collects and how it disseminates that data to the public, and even the graphics teams that it has available to make pretty websites, to make their information understandable, and the satellites they put up in space, and really all sorts of scientific work that NOAA does.

Though it is unlikely that weather forecasts would immediately become inaccurate, experts worry that cuts to NOAA would disrupt the organization’s climate models and make it more difficult to predict the changing weather as climate disruption intensifies. (Photo: Mennal, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: That's quite a huge cut for an agency that has a pretty important role in climate modeling and climate science.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, so this is the office that really invented climate modeling, in a way. It has a really interesting history. It goes back to 1955. It developed some of this first earth systems modeling and really early examination of both the planet's oceans and its atmosphere, in a way that makes it possible to not only have great weather forecasts, but to understand what's happening on the planet as a whole. There are other places, other labs, that do this now in a sophisticated way, but this department is the best and is the most sophisticated, and creates an extraordinary amount of information that really affects our lives in every way.

DOERING: And in your article, you talk about a specific laboratory that is doing a lot of this research. What makes this particular laboratory so important for climate change research?

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, so the Office of Atmospheric Research at NOAA works in part by having what they call these cooperative agreements with universities across the country, and by far the most important of them is an old collaboration at Princeton University, where they run the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, which is known as GFDL. And this is really the nerve center of NOAA's climate modeling. It is the place where they cooperatively developed this model, going back over generations, and it's a place where they run this model now as well. So, this is the place that figures out the architecture of modeling that NOAA then uses for all its different departments. And even other agencies, like NASA, borrow parts of this model, and they become like the foundation of our national weather system modeling, for example, or our national hurricane prediction and things like that.

DOERING: So of course, we're talking about the impacts to climate science climate modeling, but you're mentioning that, you know, like forecasting is involved here as well. I mean, this model is foundational for the weather forecasts that NOAA contributes to. So if some of these forecasting capabilities are curtailed or eliminated, what could be the impact on daily forecasts that we check on our phones?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, in terms of daily forecasts, I mean, I think we take for granted how good those forecasts are and how readily available information is about whether it's going to rain at 12 pm and stop at 12:15 or if it's just going to rain sometime on Sunday. That level of detail is the kind of thing that these models make possible, and it's really difficult to know what's going to happen if these cuts are enacted. It could be that the models and the lab are shut down entirely, and what they do becomes inaccessible to the public and becomes inaccessible to NOAA entirely, and that would be a really severe move, and it's hard to know how that would affect our weather forecast. The people that I talked to say that it's much more likely that their progress essentially gets frozen in place. So right now, the national weather system, National Weather Center, has taken its version of those models, and it creates our forecasts every day, and it will cease to update those models, and so the forecasts will remain as good as they are now, but not get much better. And what will happen is the earth continues to change, and we're seeing climate change, for example, really change the norms that we're accustomed to. Over time, those weather forecasts will lose the ability to understand what's happening, and they will become less accurate, and eventually they would become mismatched with what's actually happening.

DOERING: What might happen to predictions of hurricanes and other natural disasters if these funding cuts are implemented?

Proposed funding cuts to NOAA, discovered in a leaked memo from the White House Office of Management and Budget, would severely restrict a long-standing climate research partnership with Princeton University. (Photo: Zeete, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LUSTGARTEN: Well, they'll get increasingly less precise. Every May, for example, the GFDL lab at Princeton delivers an updated hurricane model to the National Hurricane Center. And the Hurricane Center puts out, famously, every May before the start of hurricane season, an updated prediction for how many storms we're going to get and where and why, and it's based off of things like the most recent readings, which NOAA has collected, of currents in the Atlantic Ocean and the temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean. And so, if we don't have an accurate forecast, we’ll be blindsided by the storms that will inevitably come, and the less warning we have, the greater the impact, and the greater you know, the destruction and the danger to the people that live in the places that they strike will be.

DOERING: So, NOAA is part of the Department of Commerce. What are the economic implications of limiting NOAA's capabilities. Can you talk about the connection between NOAA's work and the American economy?

LUSTGARTEN: I think that's the most surprising thing about this story. Americans tend to think of NOAA is an obscure science agency that maybe does important work, but it's off there in a niche on the side somewhere, and they don't realize that NOAA is deeply embedded in almost every aspect of our economy, our national security, our defense systems, right down to how our local communities or governments make decisions about planning or zoning. And it's ingrained in these ways because it produces an extraordinary amount of data. And so, this data is used, for example, by the shipping industry to not only chart what direction its tankers go in, but how they'll save fuel in doing that and avoid a big hurricane. Farmers and agricultural industry folks use not only the forecast to determine what their planting plan will be and their timing, but what kind of insurance that they'll get to protect their crops. It's a part of everything from local zoning and infrastructure planning in communities to farming and shipping and logistics and airplanes flying and just about everything else.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, just to highlight one figure from your article, you wrote that NOAA's chief economists estimate that the agency's El Nino outlooks alone boost the U.S. agricultural economy by like, $300 million a year, and corn growers save $4 billion in fertilizer and cleanup costs. That's quite a huge number.

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, that's right, and then that's because there's some little window into NOAA data that those farmers will use to understand when is the best time to apply fertilizer, for example, so that it doesn't just get washed away by the next rainstorm, or so that the soil is most able to absorb it. These are really like technical, pun intended, down in the weeds, kind of questions, but they're fundamental to how that industry works.

Without forecasts from NOAA, the United States military might have to depend on other countries for weather predictions, potentially undermining our national security. (Photo: United States Air Force, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DOERING: And how does the military use this data from NOAA, and what might be the impacts if that disappears?

LUSTGARTEN: You know, there's some ways in which NOAA data seems to affect national security issues. One is operational planning. The U.S. military has its own weather forecast system and staff, but it bases a lot of that on those same NOAA models, and with a lot of NOAA input. And so, you know, imagine you're going to send the Air Force on a strike mission, you want to know what the weather is that they're flying into, you want to know if there's an advantageous break in cloud cover. So these are the kind of strategic advantages that our really superior understanding of weather science makes possible for the U.S. military.

DOERING: How do you think other countries will respond, Abrahm, if the cuts to NOAA are enacted?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, in the short term, they will compensate. I mean, there's really good science, and scientists and models being developed in Europe, for example, in Japan. They're very capable. They will continue to do their climate work, and it will be pretty good work. The experts that I talk to point out, though, that many of the scientists leading those efforts around the world were trained at this GFDL lab in Princeton. There's a knowledge cultivation that U.S. universities have led, which NOAA has always been a big part of, and that's created and supported the science culture of research around climate science around the world. And so that begins to be undermined both the reputation and the functionality of it. And so you can see a future where in the long term, those scientists aren't as knowledgeable. Their systems aren't as well tested. They never got the immense support of billions of dollars that the U.S. government has poured into this research for a long time. And so long term, those programs could falter, or they could be invested in by Europe, for example, and they could be great, but we won't have them. And that's the other real risk that a lot of the folks that I talked to point to, which is that not necessarily that the world will lose its understanding of climate change, but that the United States will. And, in losing that, we become dependent on others. Imagine if our Air Force wants to carry out an operation in the Middle East and has to check with the Australian government first to get a good forecast. And imagine if that foreign government doesn't want to cooperate. You know, it's another link in the chain that just undercuts our ability to operate independently, and in a very strong way.

Farmers depend on NOAA’s forecasts to know when to apply fertilizer and plant crops. (Photo: Mark Stebnicki, Pexels, Pexels license)

DOERING: So as we're speaking, you know, I understand that these cuts at NOAA to climate modeling are not yet set in stone. But what do we know about the timing here and about any pushback from Congress?

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, so we know very little, unfortunately. I got no response in my reporting from either officially, from NOAA, from the Department of Commerce, from the White House, or the Office of Management and Budget. In that leaked memo from the Office of Management and Budget, the agencies were given a deadline of April 24 to present plans for how they were shifting their operations or changing their staff and their programs to comply with this memo. So we don't know exactly if those numbers will be approved, but it seems pretty clear that NOAA and the rest of the Department of Commerce have their marching orders to begin making this change.

DOERING: Abrahm Lustgarten is an editor covering climate at ProPublica. Thank you so much, Abrahm.

LUSTGARTEN: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: We reached out to the White House for comment but did not receive a response in time for this broadcast.

Related links:

- Read Lustgarten’s full story about the cuts to NOAA.

- Learn about the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory at Princeton University.

[MUSIC: Tim Franks Trio, “Flowers in April” Single, Tim Franks Trio]

Tariffs and Green Energy Cuts

The Trump Administration favors the fossil fuel industry over the clean energy industry in its tariff policies. (Photo: Arbyreed, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: The economy ranked as the top concern when voters headed to the polls last November and re-elected President Trump on his promise to end inflation and rev up the U.S. economy. So far, though, it’s been a very rocky start, thanks in part to the many tariffs the President ordered on goods imported from other countries. While some are on a 90 day pause, all imports of aluminum and steel face an import duty tax of 25% as we go to air. Some goods imported from China are facing tariffs of more than 100%. And there’s a 10% tariff on energy from Canada, a major source of energy imports for the United States. Other countries have retaliated with their own tariffs. President Trump says he is exempting fossil fuels from these import duties, which have been shifting rapidly over the past few weeks. Here to talk about the implications for both the fossil fuel and renewable energy industries is Collin Rees, the U.S. Program manager for Oil Change International. Hi Collin and welcome back to the show!

REES: Thanks so much for having me, Paloma.

BELTRAN: So, Collin, over the last few weeks, there's been a lot of inconsistency in terms of U.S. tariffs, a lot of back and forth, ups and downs. What's all of this doing to the fossil fuel market?

REES: It has certainly been a roller coaster. I think, much like the broader economy, the fossil fuel markets haven't particularly known what to do with Trump's tariffs, and in particular with the fact that they are changing day by day. I think that uncertainty, that volatility, is in fact, a feature of fossil fuel markets. Oil and gas in particular, are markets which tend to be extremely volatile in a way that can be really damaging to consumers and the broader economy. To me, this is yet another example of the dangers of being hooked to a fossil fuel economy, of having so much of our lives intertwined with oil and gas in different ways, and the dangers of Trump's policies and others to keep us hooked on that fossil fuel economy.

Recent tariffs are likely to hurt the solar energy industry by increasing the costs of the materials needed to build solar arrays. (Photo: Roy Bury, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BELTRAN: And how is this likely going to impact consumers, both at the gas pump and when they're looking at their home energy bills?

REES: It's difficult to predict the tariffs exact impacts on fossil fuels in the short term. I think one thing that we can definitely say is that in the long term, this means higher energy prices for consumers, because wind, solar, energy storage are the cheapest sources of energy available, and this is going to raise the price of renewable energy and hurt the build out. With Trump and others continuing to give preferential treatment to the oil and gas industry, to the fossil fuel industry, that's going to cause the price of renewable energy to go up. And when combined with the regulatory changes and other attacks on renewable energy and boost for fossil fuels, you're slowing the transition to renewable energy. It's not just that the Trump administration is laying the grounds for economic chaos here and raising prices on everyday goods, but it's also slashing many of the federal programs that help working people weather these economic downturns, including things like assistance paying their electricity bills, Medicaid and health assistance, food and housing assistance, even gutting things like FEMA to respond to increased weather disasters and the weather service. These are the parts of the federal government that help communities protect themselves from the fiercer hurricanes, wildfires, droughts, et cetera, all the impacts of climate change, as well as just normal disasters and to rebuild after they hit. And so, I think it's really a double whammy in that not only are they boosting the fossil fuel industry at every turn but also taking away some of the only support systems that many of our communities have to respond to those disasters.

BELTRAN: And what countries are our biggest oil and gas partners, and how are they being impacted?

REES: We have very large oil and gas exports as the United States. We're, in fact, the world's leading exporter of oil and gas combined. Over the last couple of years, we've seen a real increase in exports of gas, and LNG, as it's known, liquefied natural gas, is one form of that gas, being sent to Europe in part due to the impacts of the war in Ukraine and the pressures that has put on the energy system. One thing Europe has done as a result of that war is to aggressively invest in its transition to renewable energy. And so one of the things that the U.S. oil and gas market is sort of coming to terms with is that Europe actually won't need that much gas forever, and in fact, it might not need it for very many more years. And so what we're seeing in the market, in particular in the gas and LNG market, is a pivot toward Asia, an attempt to lock in more contracts with places like Japan, places like South Korea, places like much of Southeast Asia, to offload U.S. LNG, for instance. Asia is sort of the place where the gas market is increasingly looking to grow. So those are the places that are also impacted by these tariffs in many different ways. Already, the economics of importing U.S. LNG was pretty questionable. These are places where it is also much cheaper to build renewable energy in many cases. And so what we're seeing is this diplomatic mishmash of frankly poor economic choices, increased tariffs, which are causing global economic instability, while also diplomatic pressure to be purchasing more expensive and more volatile fossil fuels from the U.S., when, in fact, the solution needs to be transitioning to renewable energy more quickly.

In response to recent United States economic policy, China and the European Union are discussing a partnership which would enable China to export more electric vehicles to Europe. (Photo: Kritzolina, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: So it sounds like a lot of these countries are expanding in renewable energy and have a lot of renewable energy potential, but they're still importing LNG. Why is that?

REES: The U.S. has spent significant diplomatic and geopolitical resources to pressure other countries to import more LNG. This is something that's a very top priority of the fossil fuel lobby, and it's been something that's been a top priority of Republicans. Certainly, the Biden Administration as well did some of this. But under Trump and Trump's first term and Trump's second term, the international lobbying on behalf of the oil and gas industry has just gone through the roof. And as we've seen, it doesn't even just stop at that kind of public private partnership. A fracked gas CEO is now literally the head of the Department of Energy. Trump is actually bringing in these people into his administration, trying to take us back to last century's energy mix.

BELTRAN: And President Trump appears to be engaged in a trade war with various countries around the world. How is this trade war impacting the fossil fuel industry?

REES: I think that the trade war is probably not welcomed by the fossil fuel industry, frankly. If Trump's trade wars and tariffs do cause a global economic downturn or anything that even that kind of hurts economic growth, what that means is a slowing of demand in the U.S. and across the world often. And so, a slowing of demand means everything slows down. You're not only able to build less renewable energy, you're probably able to build fewer things that rely on fossil fuels, just all growth slows down. And so hyper capitalistic corporations tend to not like that sort of environment. So I think there is a severe danger here that by pursuing whatever motivation he might have, that Trump actually slows down the economy, damages the economy in different ways, that has negative impacts even on his so-called friends in the oil and gas industry, for instance. I think oil and gas are very much pegged to a global market, and so their prices are set at the global level. So even if Trump were to succeed in boosting the U.S. economy, but still damaging the global economy, that wouldn't necessarily be good for U.S. oil and gas. And so I think that's part of the conundrum they're caught in.

BELTRAN: In addition from exempting fossil fuels from his tariff policies, President Trump's policies appear to be harming the clean energy industry. Talk to me about how these trade policies are affecting the renewable energy industry.

President Trump has changed his mind about tariffs several times during his first 100 days in office. (Photo: Liam Enea, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

REES: So Trump's dangerous trade policies and kind of volatile tariffs impact the price of renewable energy. Lot of that is because the raw materials used to build renewable energy products, even for renewable energy products produced in the United States, that means things like steel, aluminum, different parts of solar panels, et cetera, many of those products are produced overseas, in China and in many other places. And so even if you're talking about a U.S. based renewable energy company that's building product here in the United States, they will see their materials costs increase significantly. There's also a decent amount of trade, still. Despite existing tariffs and trade barriers, we do import some solar panels from overseas. Those are produced less expensively than we can do it here in the United States. So, for all these reasons, solar in particular, is impacted, but the same for large wind turbines, bringing in things like large amounts of steel from overseas. Some of the European companies are some of the leading technological innovators in wind energy development. These are all reasons that we'll see renewable energy be more expensive as a result of these trade actions by the Trump Administration. I think it's also important to view this, not in isolation, as only a trade and tariffs attack. We've seen attacks on renewable energy across the board from the Trump Administration. We've seen them freeze funds to support renewable energy build-out and clean manufacturing, to make renewable energy accessible to low-income families. There's been executive orders cracking down on renewables. There's been paused permit approvals for offshore wind. There's executive orders on things like unleashing American energy, which specifically exempt wind and solar. So this has very much been an across the board attack on wind and solar and on other components of the energy transition and its infrastructure, like electric vehicles, charging networks, et cetera.

BELTRAN: And how are other countries responding to these tariffs?

Collin Rees is the U.S. Program Manager for Oil Change International. (Photo: Matt Maiorana)

REES: I think we're seeing countries realize that the United States doesn't necessarily need to be involved here, or that the U.S. is not a reliable trading partner anymore, in particular, in renewable energy and kind of alternative energy sources, but really more broadly as well. One of the things I found really interesting was just within the last couple weeks since the tariffs were announced, the European Union is talking to China about shifting regulations and significantly ramping up the import of Chinese electric vehicles and electric vehicle technology. And I think that's the sort of thing where we could see continued growth in the renewable energy industry and things like electric vehicles overseas, not including the U.S. in any way as a result of these tariffs, as countries realize that they do have alternatives to just United States products.

BELTRAN: Collin Rees is the U.S. Program Manager for Oil Change International. Collin, thank you so much for joining us.

REES: Thanks for having me, it was great to be on.

Related links:

- Learn more about Oil Change International.

- Follow President Trump’s tariff policies.

[MUSIC: Dave Brubeck, The Dave Brubeck Quartet, “Give A Little Whistle – Stereo Version” on Dave Digs Disney (Legacy Edition)]

DOERING: Coming up, how studying parrot brains can help us better understand human speech. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dave Brubeck, The Dave Brubeck Quartet, “Give A Little Whistle – Stereo Version” on Dave Digs Disney (Legacy Edition)]

Parrot Brains and Our Own

Dr. Long began his research with zebra finches since the males learn their father’s song perfectly in order to court females. (Photo: Ayacop, Accelerated Growth following Poor Early Nutrition Impairs Later Learning, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Parakeets have astounding vocal abilities. They can mimic sound effects and human speech, like when we ask Siri about something.

PARAKEET TALKING: Hey Siri, tell me about chicken. Hey Siri, Hey Bird, Hey Siri, tell me about chicken…

BELTRAN: They can do this, thanks to their brains. Though “bird brained” tends to be an insult, the brains of parakeets might hold a key to unlocking how human speech works. In a recent study published in Nature, scientists were able to match specific vocalizations to individual neural pathways in the birds’ brains. The researchers hope that their work will teach us more about communication disorders including autism, which impacts around 1 in 45 American adults and 1 in 31 American children. Here to explain is lead researcher Dr. Michael Long, Professor of Neuroscience and Physiology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine who led the study alongside Zetian Yang. Hi Dr. Long and welcome to the show!

LONG: Thank you. It's great to be here.

BELTRAN: So, we're talking to you about recent research with parakeets, but I understand that your earlier work was primarily with zebra finches. What was working with the finches like, and what did you learn from them?

LONG: Zebra finches are amazing little animals. What they're amazing at is learning through vocal imitation. And so in that species only the male sings. They listen to their father, and they memorize that song. And then over the next months, they practice all day long to try and sound like dad and and they get better and better. And ultimately, when they're about four months old, they have a very good copy of dad's song, and they use that in a courtship setting, so they sing that to the female immediately before mating.

BELTRAN: Oh, so like father, like son.

Popular imagination of a talking bird might feature a large parrot on a pirate’s shoulder, but parakeets are actually the masters of vocal imitation in the bird kingdom. (Photo: Chris from Th' L.G., USA, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

LONG: Like father, like son, exactly. And that process of learning is something that actually has deep importance for understanding how the brain works. And so there's first of all, a really exclusive club of animals that can learn through vocal imitation. And so the fact that they can do this is an amazing thing. Monkeys can't, for example, and the process of learning has taught us what it means to take up a new complex skill. So if you imagine picking up a golf club and having to do something as daunting as hit a golf ball closer to the hole than it is right now, it's a tough thing, right? And you have to orchestrate many different muscles, and the bird has the same challenge. How do you take all of these vocal muscles that make that sound and actually get it just perfect so that the female will say, "Ah, that's a good song." And you move on from there.

BELTRAN: You know so we've all seen those pirate movies where the parrot on the captain's shoulder is saying, you know, "Polly want a cracker." But you were working with budgerigars, birds many of our listeners probably know us parakeets. How close is that image of a parrot on a pirate's shoulder to a parakeet's speaking ability?

LONG: You can call them budgie for short, but budgerigar, yeah, and you can also call them the parakeet. They're the same thing, and they're a parrot species. The reason why I had been somewhat intimidated by the parrot, broadly speaking, is that this little zebra finch can do this amazing vocal imitation, but the song itself is about a second long. It takes a couple of months to learn one second. But the budgerigar is something that is incredibly flexible, and so in looking into this, the animal that has set the record for the most human words copied is actually the budgerigar, out of all the parrots, out of all the animals that exist. There was an animal in the early 90s called Puck that could actually speak 1700 identifiable words.

BELTRAN: Wow.

LONG: And so this is something that is amazing to me. How do you get a brain that can do that, that can gather different acoustic objects in its environment and turn that into something that they can fluently say to their partners? And if you look at them, they are in Australia in packs of 1000s, all chatting all day long. It's amazing. And so we thought this is going to be a very tough go. If it's taken us 20 years to try and get to how a zebra finch does its one second long song, how are we going to get to such an amazing vocal ability of this parrot, and how the brain does what it does there?

A recent study mapped out the neuroscience of how parakeets imitate sounds they hear in their environment, down to the individual neuron. (Photo: Christopher Auger-Dominguez)

BELTRAN: How were you able to learn how parakeet brains allow them to speak?

LONG: So in our laboratory, we've been really fascinated by human speech. And I think the reason there is, I think if we lose our ability to vocalize, it can really be devastating. I've personally have had relatives that have been affected by autism, by stroke, by things where they're actually robbed of their ability to fluently speak. So it's something I'm really fascinated by, and we do a lot of recordings in people, trying to understand how human brains work. But a human brain has almost 100 billion neurons, and it's really complex. Language is something that is thought to be really unique to humans. How do we get some kind of way in to understand the basic principles for how this works, if there isn't really a good animal model for that? And so what we've decided to do is say, "Let's take a step back. And language is a multi-faceted thing, and different animals have different specialties and different aspects of what they can do." One example is a Costa Rican rodent called the singing mouse, and we could look at their vocalizations with each other. They don't learn what they're singing, but what they do is actually use it in these kind of conversational exchanges with other rodents. So you can see them going back and forth as they're trying to negotiate space within the lab. They do this to talk about territory. This is my home range. Zebra finches learn their song. And so what we wanted to do with the budgerigar is to say, how do you take something that's so flexible, that's so vast and so intimidatingly rich, this ability to pick up words, to pick up all these environmental sounds. And so my naive question walking in is, is their brain going to be processing this information in a way that looks human like or zebra finch like? When we did our recordings, our first ever functional recordings in the brains of these parrots, what we found was something that was distinctly human like. So the way that this works, even though the kind of architecture of the brain is avian in nature, right, the dynamics that allow them to create these sounds was something that looked a lot like the kind of recordings that were made in humans in intercranial settings over the past many years. And I'll give you an example.

There are brain cells in the parrot's brain that are active when the bird speaks sounds that are consonant-like, others that are active during vowel sounds, others that are active during high and low tones. And we do see something that looks just like this in the human brain.

So in this sense, we've uncovered an animal that uses that same strategy of a very simple kind of set of cells that allows us to in combination form words and how that process breaks down, is something that I think can give us a real clear view into communication disorders.

BELTRAN: And how were you able to map out those vowel sounds? What technology did you use for this study?

LONG: There were many things that had to happen here. So one thing is, it don't mean a thing if you can't have them sing. And so we had to build a special cage that allowed them to feel comfortable enough to produce their song, and so we built this kind of social cage. We can do brain mapping of a single bird, but then give them access to many birds that they can chat with. You know, these birds can't be by themselves. They're incredibly social. Our veterinarians won't let us keep them by themselves, and we would never want to do that kind of thing. They're constantly chatting societies of other birds. This is what they're evolved to do. And so number one was working with a really amazing cage company called Corners Limited in Kalamazoo, Michigan. And they made for us a kind of social cage in which there was a compartment with a bunch of birds hanging out that this bird could talk to, and another compartment that could safely allow us to record from that bird's brain. Often, if we put two in the same compartment, then you'll see them starting to interfere with our recording apparatus, and all of that. A second innovation is a small probe that can go into the brain that's very lightweight. We want this bird to be able to carry it comfortably. The brain has no pain sensors, so this is something that is fine, and we can also remove that probe when we're done. And the bird can be just fine to go about what it does. It's an incredibly thin, small probe that goes directly into this area of the brain and allows us to have single neuron resolution, to pick up about 100 simultaneous cells and really map this out for the first time. It's the first time any neurons have been recorded in an awake parrot species of any type. And we look in and we see this human-like map. It was a really thrilling moment for us.

BELTRAN: Dr. Long, why study parakeets to better understand human brains?

Communication disorders impact around 15% of Americans. Michael J. Fox, who has Parkinson’s disease, is a famous example. (Photo: Chuck Kennedy (Pete for America), Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

LONG: I think it's because of their incredible vocal abilities. They mimic a wide range of sounds from the environment. Even our animal caretaker said that when she was squirting water into their dishes, they do a fantastic impression of just that sound itself, you know. So everything that they hear they can grab, almost like taking shiny objects and bringing it to their nest. They do this acoustically. The ability to pick up all of these different vocalizations really on the fly is something that is exciting to me. It doesn't take months and months to learn a single thing. They're very astute, and they can pick things up very quickly. We're working now with a team at Stanford to try and understand how to speak budgerigar. And so this is something I think is really exciting. And we can basically put a head-mounted camera on these birds, and we can see what they see as they're making these different sounds. And if we can then relate what they're seeing to the sounds that they're making, we can start to see how they construct sentences, and how they could potentially convey information in a meaningful way from one animal to the next. And this is something we're really excited about.

BELTRAN: Is the hope that we will eventually be able to communicate with these birds with language?

LONG: Well, I think the hope is there's this notion of human exceptionalism, where language is something that really is something that only we can do. So I think the idea of expanding beyond what we can do, and more than that, really creating a model for how language works in a much simpler brain that gives us some fighting chance of fixing language when it breaks.

About 15% of our population suffers from a communication disorder, and this is anything from aphasia following a stroke, neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease and age-related dementia, and neurodevelopmental conditions like autism. And I think because of this similar vocal capacity, the budgerigar brings renewed hope for understanding and allows us to maybe give their voice back to people who've lost it. That's something that would be really meaningful for me.

Video courtesy of Dr. Michael Long

BELTRAN: You know, you mentioned autism, and I know that chimpanzees and other great apes don't have the same vocal ability as parrots, but their brains and social lives are much more similar to ours. How could we study something like autism in a bird when their social lives are even more different from ours than our great ape cousins?

LONG: Right, so each animal model, we value it for its perspective that it gives us to such a difficult, multifaceted thing, like language. I would argue the first attempt we're going to take to try and look at autism will come from those singing mice that I mentioned before. We're actually creating an autism model using gene editing in those singing mice. So the idea there is Shank3 is an autism risk gene. And we're using gene editing to try and knock down that gene to ask how that affects communication, and how that affects how the brain of these animals is engaged during this kind of social exchanges. And our very first litter was born two weeks ago. So we'll find out where things are in the very near future. Hopefully we'll talk again and tell you all about it.

BELTRAN: And what are the next steps for this research?

LONG: I think the two major next steps, at least in my view, number one, you know, what are they saying? We want to find out, are their sounds related to specific actions or objects in their environment, and how do they actually express that to another bird. And also, I think, who's playing this keyboard? And so, the idea of just such a simple motor representation of different vocal sounds, now we have to find out how that's exploited by the bird in order to flexibly make whatever sounds they want to make. They're easy to state questions, but they're really tough to get a hand on, and we're making a good run at it.

BELTRAN: Michael Long is professor of neuroscience and physiology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Michael, thank you so much for joining us.

LONG: Thank you. This was fantastic.

Related links:

- Read Dr. Michael Long and Zetian Yang’s original study.

- Learn more about parakeets.

- Explore more of Dr. Long’s work.

[MUSIC: Offthewally, “Tremellow” on Surfari, Jake Harris]

Listener Postcards

Disney World in Florida harbors some unexpected oases. (Photo: Tech. Sgt. Andrew Burdette, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BELTRAN: Here at Living on Earth amongst our staff we’ve been enjoying the audio you, our listeners, have been sending in. And we wanted to remind you that summer brings the perfect opportunities to record and share your sounds!

DOERING: That’s right, Paloma! Whether you’re planning your next trip to a National Park, a campground or the beach, you can share a glimpse of that experience with us through sound! Like this recording Catherine Crow captured from a treehouse villa at Disney World in Florida.

[SOUND FROM TREEHOUSE]

DOERING: Catherine said “you wouldn’t know you were in the middle of theme park central”!

BELTRAN: Wow! Or this mockingbird song by Craig Claudin taped while he and his wife were visiting family in Phoenix, Arizona.

[MOCKINGBIRD CALLS]

BELTRAN: Craig said this was a gracious and unexpected gift from a natural composer.

A mockingbird in Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo: Banalata Pal, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

DOERING: Well, I couldn’t agree more with Craig. To capture sound you can use any sound recording app on your phone, like Voice Memos or Voice Recorder. And for the best audio quality make sure to stand still for at least two minutes without fidgeting or talking. But we do want to hear from you!

BELTRAN: Yes we do! So be sure to speak clearly and let us know where you are, what you’re hearing and what inspired you to record the moment. Then you can email the file to comments@loe.org, and we might just use your audio postcard on the air! That’s comments at loe dot org.

Related links:

- How to make a sound recording on an iPhone

- How to make a sound recording on an Android

[MUSIC: Offthewally, “Tremellow” on Surfari, Jake Harris]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and We always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth