October 21, 2022

Air Date: October 21, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

California Wind Power Breakthrough

View the page for this story

As part of President Biden’s goal to supply 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030, the Biden administration announced an upcoming sale of federal leases for innovative floating offshore wind sites in the deep waters along the California coast. The wind energy sector is also getting a boost from the clean energy tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act and additional support in the bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Adam Stern, executive director of Offshore Wind California, joins Host Steve Curwood to explore the bright future for offshore wind in the state and why the oil and gas industry has expertise that can be put to good use for this untapped resource. (09:29)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering take us beyond the headlines with a look at how PFAS “forever” chemicals are contaminating everything from North Carolina alligators to the blood of residents in Okinawa, Japan. In some good news, the two investigate how the creation of artificial ponds has helped frog populations in Switzerland. Finally, the two open the history vaults to look at some misconceptions about the 1972 Clean Water Act. (05:33)

Parking Reform and Climate Change

View the page for this story

Suburban sprawl adds to climate disruption by promoting driving and to accommodate commuters, some 30 percent of urban land is already devoted to parking. Even more spaces are often required when buildings are constructed or renovated. Now some cities and states, including California, are steering away from parking space mandates. Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at Columbia Business School, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what parking reform may look like for cities. (07:55)

Fat Bear Week and the Salmon Behind It All

View the page for this story

Every year Katmai National Park in Alaska hosts Fat Bear Week, a competition to determine voters’ favorite chubby brown bear, because come autumn a fat bear is a healthy bear with plenty of fat reserves to get them through the long frigid Alaskan winter. Katmai National Park ranger Felica Jimenez joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss this year’s winner, how much weight bears gain before hibernation, and why salmon are the unsung heroes of Fat Bear Week. (08:23)

Wishful Thinking: Leopards of the Olare Orok River

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Young leopards may look like formidable hunters, but they still have a lot to learn. In the Maasai Mara savannah, on the banks of the Olare Orok River, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tracked one young leopard’s learning curve. (03:35)

Saving Big Forests to Save The Planet

View the page for this story

Protecting the remaining intact big forests on Earth offers a low-cost and highly beneficial way to mitigate the climate crisis. The new book “Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet”, coauthored by economist John Reid and the late ecologist Tom Lovejoy, puts a spotlight on these so called “mega forests”. John Reid joined Host Steve Curwood to describe these majestic places, the threats they face, and why they are worth protecting. (11:48)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

221021 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Felicia Jimenez, John Reid, Adam Stern, Gernot Wagner

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Wind in the sails of clean energy off the West Coast.

STERN: We're fortunate to have the marvelous engineering achievements, largely developed by the oil and gas industry, to create floating platforms which is going to unlock offshore wind resources that would otherwise not be available. We're going to be able to get use of some of the most powerful resources in the world.

CURWOOD: Also, celebrating the jumbo-jet sized champion of Fat Bear Week.

JIMENEZ: The winner this year was Bear 747. He was identified as a sub adult. And when he was first seen, he was actually really small. But he's definitely grown into his number. In 2019, he was estimated to weigh about 1,400 pounds.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

California Wind Power Breakthrough

9.5 MW floating wind turbine deployed at Kincardine Offshore Wind project off coast of Aberdeen, Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of Principle Power)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Nowhere is hungrier for more renewable energy than the state of California, with reduced hydropower output this summer during a blistering heatwave and drought. But help is now on the way. In a game changing move, the Biden Administration just announced that bidding for federal leases for floating offshore wind sites along the California coast will begin December 6th.

CURWOOD: Ocean water is so deep close to the California shore that fixed platforms aren’t practical, but there is plenty of space for floating turbines. Adam Stern is executive director of Offshore Wind California, a trade association, and he says innovation and federal support are making a breakthrough in converting the energy economy. Adam Stern, welcome to Living on Earth.

STERN: Well, thank you. It's a pleasure to be on your program.

CURWOOD: Let's start with the Biden administration just announcing the first ever offshore wind lease sale off California's coast. How's this going to work? And what does this mean for offshore wind?

STERN: This is a very exciting moment that has been building for several years now. What the announcement meant today was that the Biden administration is going to conduct a lease auction for five lease areas off the California coast. They collectively could produce as much as five gigawatts of electricity, enough to power 4 million or more homes in California and be a critical addition to California's clean energy grid for the future.

CURWOOD: Along with the announcement of the offshore wind leasing sale for California, how does the Inflation Reduction Act and its tax credits affect the outlook for the wind energy sector, in California in particular, but also generally, as well?

My Administration has set a course for deploying 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 – enough to power 10 million homes.

— President Biden (@POTUS) September 17, 2022

And we’re taking new steps to develop floating turbines that will unlock more clean energy and create jobs up and down the supply chain.

STERN: There are some excellent provisions in the IRA that will help the offshore industry nationally. In particular, there's an investment tax credit, that goes up to 30% of the costs of building the offshore wind farms. One critical element of that, Steve, is that they've extended the credits to 2045, which reflects the sustained effort that will be required to build out offshore wind nationally. And then there are also tax credits to support manufacturing of the components of offshore wind farms: the towers, the blades, the platforms that are necessary to construct offshore wind towers. In addition, the IRA includes transmission planning grants, and then separately, the infrastructure law that was passed before the IRA has funds in it to support port development, as well as transmission upgrades to critical things that are necessary to advance offshore wind.

CURWOOD: In sum, how has the market for wind energy, particularly offshore wind energy in California, been changed now by these developments?

STERN: Well, we're just in the middle of one of the most exciting periods of policy momentum that I think California and the nation has ever seen. Just a few months ago, the state committed to a planning goal of five gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 and up to 25 gigawatts by 2045. That together with the Biden administration's initiatives to announce the time and date of the auction for the first leases off California, these together present, I think, a very promising future for offshore wind and enable us to take advantage of this resource that up until now has been untapped.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the floating platforms that are going to be required for this. This really hasn't been done much in this country at all, if I understand correctly.

STERN: We're fortunate to have the marvelous engineering achievements, largely developed by the oil and gas industry, to create floating platforms, which is going to unlock offshore wind resources that otherwise would not be available. And with the floating platforms tethered to the bottom of the ocean with cables, and supported by very advanced technology that helps them to be positioned in areas that maximize the wind resource, we're going to be able to get use of some of the most powerful resources in the world. And on top of that, we're going to be able to have these offshore wind farms located 15 to 20 miles offshore. It opens up 60% of the waters that would otherwise not be usable for offshore wind.

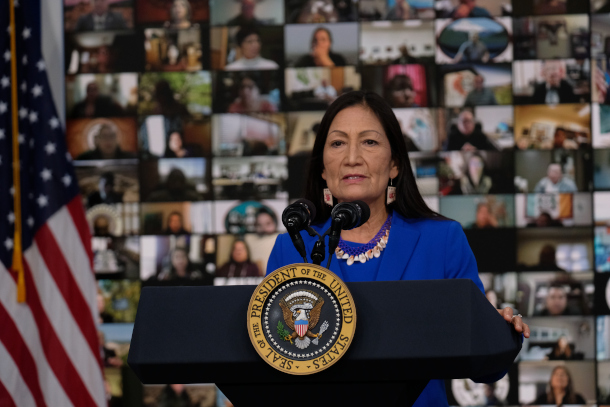

Secretary Deb Haaland is a champion for offshore wind energy and worked to develop the Biden administration's plan to supply 30 gigawatts of offshore energy by 2030. (Photo: US Department of Interior, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I guess there's a maintenance advantage, too, huh?

STERN: Yeah, there's an exciting aspect of this, which is that you can actually take an individual wind turbine and tower and disconnect it from its mooring lines, tug it into port, have it go through a maintenance regime to fix and replace any broken components, and then tug it back out and put it in position for years of additional service.

CURWOOD: So on that point, what are the risks environmentally, of having these big floating platforms with wind turbines on them?

STERN: In California, at least so far, the studies that the Federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has done determined that the impacts would be minimal. We want to protect marine and coastal resources. I believe this is a time we can have clean energy and a healthy environment, and it's critical to the task we have ahead of ourselves of fighting climate change.

CURWOOD: And what about the birds? Some people say, “Oh, those big blades get the birds.”

STERN: By being 15 to 20 miles out, we'll be away from the densest population of birds, but there will be some. And there are also efforts to learn about the migration patterns and if necessary, adjust some of the operation schedules of the offshore wind towers.

CURWOOD: Adam, tell me what new technologies and innovations are you hoping to see to support offshore wind energy?

STERN: See, one of the most exciting developments about offshore wind is that it offers the promise of developing an entirely new clean energy industry for California and the nation. With tens of thousands of jobs, we are already seeing the transition underway where positions that existed in oil and gas have a lot of skills and experience that can be used in offshore wind, and we're excited to advance and accelerate that transition. We also will be able to take advantage of the floating platform technology, which has been now tested in significant size and those floating projects are growing in scale. And by the time the projects will be built in California, we'll be able to make them large enough so that a single tower and turbine setup can generate as much as 15 megawatts of power.

CURWOOD: That's a lot of power. I mean, that's pretty huge.

STERN: The scale is really impressive. And that's one of the most exciting aspects of this. The fact that we can bring this power at a time of day when we need it most going forward as we work to electrify everything. Offshore wind has a wonderful complementary characteristic to support the onshore solar and onshore wind and hydro that we already have in our clean energy portfolio.

The Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island is the first US offshore wind farm. According to US officials, most offshore wind farm sites in the United States are in deep-water areas such as off the coast of California and Oregon that require floating platforms unlike the fixed ones pictured above. (Photo: Dennis Schroeder, Flickr, NREL, CC-BY-ND-ND-2.0)

CURWOOD: Adam, to what extent was the Inflation Reduction Act, was that legislation necessary in order to give meaning to the government's call that they're going to start leasing for offshore wind energy in California?

STERN: It's an enormous boost. This is a critical element in bringing the cost of offshore wind down to competitive levels. Another complementary initiative that the Biden administration launched just a few weeks ago, is an offshore wind shot program. And the goal of the floating wind shot program is to bring the cost down by 70% by 2035, and have 15 gigawatts of offshore wind in the United States off our coasts, also by 2035.

CURWOOD: So Adam Stern, talk to me about your association. What businesses are part of Offshore Wind California?

STERN: Our business group is a coalition of offshore wind developers and technology firms. They include a mix of pure renewable energy companies and then others that are actually oil majors, like BP and Shell who are seeing the future in offshore wind and are excited about the California market. They have a lot of experience building big projects in deep ocean waters, a lot of technology that they've used in oil and gas extraction, which is now being repurposed for the benefit of developing renewable energy in our oceans and taking advantage of the powerful winds that we have off our coasts. In a way, Steve, we're seeing the transition from fossil fuel to clean energy in real time.

CURWOOD: Adam Stern is executive director of Offshore Wind California. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

STERN: It's been a pleasure to be on Living on Earth with you, Steve. Thank you.

Related links:

- U.S. Department of Interior | “Biden-Harris Administration Announces First-Ever Offshore Wind Lease Sale in the Pacific”

- More on the numbers of what the Inflation Reduction Act includes

- Statement about the Dec 6, 2022 lease auction by Offshore Wind California

- Learn more about Offshore Wind California

[MUSIC: The Derek Trucks Band, “This Sky” on Songlines, Sony BMG Music Entertainment.]

CURWOOD: Coming up – curbing mandatory parking minimums to put the brakes on suburban sprawl. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Derek Trucks Band, “This Sky” on Songlines, Sony BMG Music Entertainment.]

Beyond the Headlines

Auto-immune problems in North Carolina alligators have been linked to PFAS levels in the reptiles’ systems. (Photo: Todd Fowler, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he's on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey, Peter, what do you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, Hi, Jenni. There's a story that concerns PFAS, those "forever chemicals" that have been so much in the science and environment news lately for some of the health risks that they may cause. One PFAS study that's come out recently looked at alligators along the coast of North Carolina. The study, led by North Carolina State, found autoimmune problems in alligators linked to levels of PFAS in their systems. Reptiles do not normally get infections, but they're finding infected alligators in some of the swamps along the Cape Fear River.

DOERING: Wow, Peter, PFAS and alligators. That's not exactly two things that I thought would really go together in a story.

DYKSTRA: No, and you don't think of alligators as an indicator species for what may be a problem for humans. But they have a long history that goes back to research done by scientists like the late Louis Guillette and the late Theo Colborn. They did early studies on the impacts of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Guillette particularly looked at alligators in Florida and found reproductive problems with alligators that were linked to endocrine disrupting chemicals in their system.

DOERING: And like endocrine disruptors, PFAS chemicals are pretty widespread in our society these days, huh?

DYKSTRA: They are. There's another recent study that tallied up 57,000 potential locations of PFAS contamination, near military bases, near airports, places where firefighting foam has been used, posing a potential risk to humans. And also another place where US military bases are implicated is in Japan. Another study that's just come out found that Japanese citizens on the island of Okinawa, where there's a heavy US military presence, had blood levels of PFAS two to four times the normal levels found in Japan.

According to a recent study, individuals in Okinawa, Japan—which has a heavy U.S. military presence—had 3 to 4 times the national average of PFAS in their blood. (Photo: U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Wow, one can only wonder what kind of impacts those PFAS levels are having on the people there.

DYKSTRA: One can only wonder, and one can also research so we know more and more each year. But right now the news is not good.

DOERING: Yeah. Well, Peter, we've got a story about reptiles. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Let's move over to amphibians and frogs. In Switzerland, endangered frogs are making a comeback because of human intervention. Over the past two decades, volunteers and conservation groups have dug 422 artificial ponds to encourage new populations of frogs. And it's a little bit of good news that may or may not be replicated elsewhere.

In Switzerland, the European tree frog is among the endangered species bouncing back after conservationists and volunteers created hundreds of artificial ponds. (Photo: John P Clare, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Well, what kind of frogs are we talking about here, Peter?

DYKSTRA: The European tree frog was one whose population had collapsed. And those ponds have helped recover that one endangered subspecies, at least in this one area, and helped give some hope for frogs, not just in Switzerland, but throughout the world.

DOERING: Thank you for that good news, Peter. What do you have for us in the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: It's the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act. And the first thing I want to do is clean up a little historical misinformation that's tended to grow. Richard Nixon has gotten all this credit about being the environmental president who signed the Clean Air Act into law. He signed the Endangered Species Act. He signed into being agencies like NOAA and the EPA. But Richard Nixon did not sign the Clean Water Act. He actually vetoed it when he was persuaded that the costs of clean water were too expensive. But what happened is something that does not happen in this day and age. A bipartisan pro-environment Congress overrode Nixon's veto, made the Clean Water Act law, and it's made a huge difference, not meeting every one of its goals over fifty years, but meeting quite a few of them.

The Charles River in Boston and Boston Harbor were infamous for “dirty water” until the Clean Water Act, signed fifty years ago this week, helped improve water quality. (Photo: Chris Rycroft, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, here in Boston, we used to have that "dirty water" that people love to sing about, Peter.

DYKSTRA: That's right. It's one of my favorite songs. Of course, it's the Red Sox theme song. But that "dirty water" isn't nearly as dirty, even though the band that wrote that song hadn't set foot ever in Boston. They just heard about how dirty the Charles was.

DOERING: It was legendary dirty water. Thank you so much, Peter, as always. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And I guess I'll say, see you later, alligator!

DYKSTRA: See you later, alligator, and alligators don't love that "dirty water."

DOERING: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Frontiers in Toxicology | “Blood Concentrations Of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Are Associated With Autoimmune-Like Effects In American Alligators From Wilmington, North Carolina”

- Environmental Health News | “Toxic PFAS Pollution Is Likely At More Than 57,000 US Locations: Report”

- Environmental Science and Technology Letters | “Presumptive Contamination: A New Approach to PFAS Contamination Based on Likely Sources”

- NHK World: Japan | “Blood Tests Detect 2 To 4 Times National Average of PFAS In Okinawa”

- BBC | “Conservation: Explosion in Frog Numbers After Mass Pond Digging”

[MUSIC: The Standells, “Dirty Water” on Dirty Water (Expanded Edition), UMG Recordings.]

Parking Reform and Climate Change

California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill last month prohibiting minimum parking requirements in hopes to reduce vehicle emissions and free more space for housing and businesses in urban areas. (Photo by flightlog, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Suburban sprawl not only promotes social isolation and destroys wildlife habitat, it also adds to climate disruption as only one percent of cars these days are EVs and people in the ‘burbs do need cars to get around, as well as places to park them. To accommodate commuters coming in from the suburbs some 30 percent of urban land is devoted to parking, and more spaces are often required when buildings are constructed or renovated. In fact, so much land is taken up by parking that some economists say those mandates drive up the price of urban real estate, crowding out affordable housing and walkable retail. Now some states and cities are steering away from parking space mandates with measures like Assembly Bill 2097 in California. Gernot Wagner is a climate economist at Columbia Business School and he’s here to take a closer look at what parking reform could look like. Gernot, welcome back to Living on Earth!

WAGNER: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: Professor, what exactly are parking mandates and how is it pushing people to live farther away from cities and into suburbs?

WAGNER: Parking mandates are sort of this, this funny thing that's been with us essentially forever, that is requiring homebuilders, homeowners, commercial builders to provide a certain number of parking spots. Because government subsidizes heavily suburbanization, driving, and the more parking spots we have in the city or at the fewer homes, the further people will live from wherever you want to go. And the cheaper in the all encompassing sense of the term, it suddenly is to drive.

CURWOOD: So just how much parking do we have in the United States and particularly in cities?

WAGNER: Well, too much is the short answer. Silicon Valley, for example, not even counting individual homes, there is two or three parking spots per car, just waiting around, sitting around. If you add it up nationwide, we have 2 billion parking spots for something like 280 million cars.

CURWOOD: You have looked at Los Angeles, and the parking situation there and have some numbers in an article you recently wrote. Talk to me about those numbers you see around LA and parking.

WAGNER: Every thousand square foot restaurant or bar in LA must provide at least 10 parking spots, which ends up with the restaurant being about half the size of the parking lot. Right, the bar owner, the restaurant owner, would love to have more space for customers, just sits there unused. None of this is natural or is driven by market forces, but is required to overbuild.

CURWOOD: Now, from what I hear there's this bill in California to eliminate parking minimums. Talk to me about it. I think it's called AB 2097, Assembly Bill 2097. What exactly does it entail for housing and parking space?

As parking minimums take away spaces to develop low-cost housing in cities, developers continue to create housing further away from cities and into the suburbs. (Photo: Roadsidepictures, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

WAGNER: So I am very happy to say that Governor Newsom, in fact has signed this bill into law already. So Assembly Bill 2097, eliminates parking mandates across the state. It requires a rethinking of the way we, or Californians in this case, have thought about development for a long time. What we have seen over the past years, decades of essentially saying, "No no no, I like my single family home here. We, you know, yes, we need more housing, but build it over there, not here." And these parking minimums have contributed to just this sort of development, driving up home prices in cities and leading to ever more development in, you know, further out in the suburbs, leading to greater vulnerability to wildfires, and lots of other unsavory consequences.

CURWOOD: Yeah, how is parking related to poverty and homelessness?

WAGNER: So us under building, massively under building homes in cities, while reserving spaces for cars, and all of that, in many ways, up to a point isn't government creation. It's a creation of the minimum parking requirements, which leads to fewer homes, fewer apartments, fewer houses being built, and the trade off is pushing people further out into suburbs.

CURWOOD: What connections can you show between getting rid of parking minimums and reducing carbon emissions?

WAGNER: The most direct connection is that cities cut carbon. The average urbanite emits somewhere around half, perhaps even only a third of the CO2 of the average person, the average household in the suburbs. And it's actually pretty striking to look at the overall picture. So, you know, living on the land off the land, in a truly rural environment is fantastic. But what's the compromise? Compromise is nature, the climate and frankly, time stuck in traffic. But back to the big picture, yes, cities do cut carbon.

CURWOOD: So somebody's listening to us though, Gernot, would say if you get rid of parking spaces, how are you going to get around?

Gernot Wagner is a professor and climate economist at the Columbia Business School. (Photo: Courtesy of Gernot Wagner)

WAGNER: Urbanites, like myself, right, who don't need or want cars have it relatively easy. You have basically everything within walking, biking distance, including your office, including the playground. And of course, it's it's a different vision for how to organize society for awesome suburbia, whereas some others simply depend on the car. And to be clear, the right number is not one parking spot nationwide per car. We need more parking spots because otherwise you don't get around, right? It's not like you take your car and just, you know, go in circles and come back to where you started. No. On the other hand, it is also pretty clear that 2 billion parking spots for 280 million cars is a massive overbuilding.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some examples in other cities or countries where there is parking reform and there are no parking minimums.

WAGNER: Amazingly, there are in fact, in this country in the US, there are some cities and frankly, lots you wouldn't necessarily expect to, who just recently got rid of their own minimum parking requirements. Santa Monica, California is an example, Raleigh in North Carolina, Hartford, Connecticut, Buffalo, Upstate New York. All of them got rid of their minimum parking requirements. Now, they've all done so recently, right, so it's not like there's been already a revolution on the way. Those who used to live in single family homes outside the city still for the most part do. But more homes are being built fewer parking spots, fewer on street parking, they are some cities who actually went a step further. So San Francisco actually sticks out, Branson, Missouri. They went as far as to adopt parking maximums, limiting how much parking could be provided.

CURWOOD: Gernot Wagner is a climate economist at the Columbia Business School. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WAGNER: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Bloomberg | “The Next Step on Climate Action: Parking Reform”

- Bloomberg | “Free Parking Is Killing Cities”

[MUSIC: Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi” on Joni Mitchell Tribute by Strings Attached]

Fat Bear Week and the Salmon Behind It All

Bear 747 is 2022’s Fat Bear Week winner, estimated to weigh around 1,400 pounds. (Photo: Courtesy of L. Law, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

DOERING: Katmai National Park and Preserve in southwest Alaska is part of a vast boreal forest that is vital for ecological balance and protects large numbers of grizzly bears. To get through the long frigid Alaskan winters these bears need to pack on the pounds, and some get so big humans now have a competition called Fat Bear Week. The winners aren’t necessarily the baddest bears, but they’re among the biggest. Fans from around the world vote online for their favorite of the massive brown bears captured on camera. The competition this year was so intense that the staff at Katmai even had to sniff out voter fraud. Of course, the bears were blissfully unaware of that and just kept on feasting on the plentiful salmon in the Brooks River. Felicia Jimenez is a park ranger with Katmai National Park and Preserve and she’s here with the details of Fat Bear Week 2022. Felicia, welcome to Living on Earth!

JIMENEZ: Hi, thank you for having me.

DOERING: So who won this year? What are some fun facts about the winner?

JIMENEZ: The winner this year was Bear 747. This is actually his second crown, which is really well deserved because he's a massive bear. He's probably one of the largest brown bears on Earth. And in 2019, he was estimated to weigh about 1,400 pounds. He is one of the most dominant males in the Brooks river hierarchy. And he actually starts off pretty massive already, usually emerging from the den still carrying some of his weight from the previous year.

DOERING: Wow, that's amazing. That's a huge bear. So with the name like 747, was that just a random string of numbers that he got? Or was it you know, this is a big bear, we need to give it a big Boeing 747 sized name?

JIMENEZ: Yeah, it's funny. It's a coincidence. He was identified as a subadult. And when he was first seen, he was actually really small. But he's definitely grown into his number. It's pretty funny.

DOERING: Wow, the comeback kid, I guess. So last time, we covered fat Bear Week, Holly was the big winner. How did she do this year?

Bear 435, Holly, was the runner-up in this year’s Fat Bear Week. (Photo: Courtesy of L. Law, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

JIMENEZ: Yeah, Bear 435, Holly, she did really well this year still. This year she actually just emancipated her cub 335, as a subadult who was also in the competition. And returning as a single bear kind of gave her a little bit of an advantage because she doesn't have to provide for a cub, she doesn't have to, you know, sacrifice those resources. So she could just focus on feeding herself. And it proved to pay off. She did really well as a previous winner. She started with the first round by, she won her first matchup against Bear 164, and then in the semifinals, she went up against 747. And she did lose. But even though she lost, she is still doing really well. She looks really massive, and she's definitely gained enough weight to set herself up for a successful hibernation.

DOERING: Oh, that's really great. Now I was wondering, so, of course, there are male winners, there's female winners. What about when a bear is an expecting mother? Does that sort of add some bulk and maybe give them a little bit of an edge in Fat Bear Week?

JIMENEZ: In the biographies it probably does, because it's a subjective competition. And maybe people see in their biographies, oh, this is a sow with cubs, I'm gonna vote for her. But for the most part, biologically, bears actually have a really cool thing called delayed implantation. So those embryos will not actually implant in the uterus without gaining substantial fat reserves. So I mean, a bear could have mated and have those embryos there, fertilized eggs there, just waiting. But they won't actually implant until they reach hibernation, and they've gained enough fat. So sows actually have a higher stake in gaining those fat reserves.

DOERING: Wow, that's amazing. So they're just hanging out until their body's ready to have a pregnancy. They're just waiting and eating all the salmon they can possibly find, right?

JIMENEZ: Yeah, yeah. And I mean, if a bear gains more weight, potentially they could have more embryos implant so that means more offspring. So that's a really, really cool fact about bears.

Bears congregate at Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park every year to catch salmon and bulk up before they hibernate. (Photo: Courtesy of L. Law, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

DOERING: Who were some of the runners up and who were you secretly rooting for?

JIMENEZ: So in the final bracket, Bear 901 was the runner up, and I really wanted her to win. She was kind of a dark horse during the competition, but she very quickly gained a following. And it's easy to see why she gained such a following. She started off really, really small when she showed up in the beginning of the summer, and she's ballooned into this massive blimp of a bear. She was clearly very successful at gaining weight for the winter. And she's had such a massive transformation and did so well as a completely unknown bear making it to the final round. Even though she didn't win, I'm sure we'll see big things from her in future competitions.

DOERING: So how much weight are we talking about in Fat Bear Week? How much do they weigh when they come out of hibernation in the spring, and they start eating these salmon in the Brooks River, and throughout the summer, they gain all this weight and how much are we talking?

JIMENEZ: It's a lot, yeah. Males typically can start between six and 900 pounds in the beginning of the summer. And then they can weigh anywhere, you know, over 1,000 pounds. And I mean 747 is estimated to weigh about 1,400 pounds. It's a big transformation. Sows can weigh in the beginning of the summer between four and 600 pounds and then they can get anywhere within the 700-to-900 pound range. So it's about a third of their body weight that they're losing when they're in hibernation, and then they emerge from the den.

DOERING: And this food that they feed on, mostly salmon, I believe, maybe berries as well, but like, tell me about that food source and why they're so good at putting on that weight really quickly.

JIMENEZ: Yeah, yeah, it's mostly salmon. In Katmai National Park, it's the sockeye salmon. They're really the unsung heroes of the competition. Without that strong sockeye salmon run, we wouldn't have Fat Bear Week. The timing of the bears showing up at the Brooks River coincides with that salmon run and July is when the run starts. And so we'll see a lot of the bears concentrate in the Brooks Falls area, because that's where the salmon are swimming upstream to spawn. And then we'll see the bears concentrate once again, in the lower portion of the river in September, when the salmon have spawned out, they're dying. So they're washing up on the shores of the river, and then the bears can just pick them off. So it's mostly those two months when we see our highest concentrations of bears. That's what's supporting the weight gain of the bears during the summertime.

Fat Bear Week would not be possible without a healthy sockeye salmon run on the Brooks River. (Photo: Courtesy of Russ Taylor, Katmai National Park and Preserve)

DOERING: In a lot of the West we've heard about salmon populations declining. But how are the salmon doing up in the Brooks River and Brooks Falls area where these bears get so fat over the course of one summer?

JIMENEZ: Yeah, that's actually a big cause of our celebration. We're very, very fortunate at Katmai that our sockeye salmon run is doing so well, especially with the Bristol Bay watershed that salmon run was actually record breaking this summer. But we do know that it's not like that in all places of the world. It's also not a guarantee for Katmai. And Fat Bear Week allows us to exemplify just how pristine our sockeye salmon run is doing. Because it's not like that everywhere.

DOERING: Felicia, what's your favorite part of Fat Bear Week?

JIMENEZ: Last year was kind of my first year seeing that Fat Bear Week was a thing. I think my favorite part of Fat Bear Week is just seeing, you know, behind the scenes, how much joy it brings people and how people are so excited and schools want to participate, people in, like, offices want to participate. I love seeing it.

DOERING: Felicia Jimenez is a park ranger with Katmai National Park and Preserve. Felicia, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

JIMENEZ: Thank you for having me. It was a lot of fun.

Related links:

- Learn more about Fat Bear Week and see previous winners

- Click here to view Katmai’s bear webcams

- Visit this page to learn more about delayed implantation

- Plan your visit to Katmai National Park

[MUSIC:Jerry Garcia and David Grisman, “Teddy Bears Picnic,” on Not For Kids Only, by John Walter Bratton and Jimmy Kennedy, Acoustic Disc ]

CURWOOD: Coming up, the five great mega forests of the world are key protectors of the climate. Find out why just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC:Jerry Garcia and David Grisman, “Teddy Bears Picnic,” on Not For Kids Only, by John Walter Bratton and Jimmy Kennedy, Acoustic Disc]

Wishful Thinking: Leopards of the Olare Orok River

Although leopards are often regarded as nocturnal animals, it’s not uncommon for visitors of the Maasai Mara on the banks of the Olare Oruk River, to see them during the day. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Leopards are the only big cat species that live in rainforests as well as dry regions, and in either setting young leopards may look like formidable hunters but they still have a lot to learn. In the Maasai Mara savannah, on the banks of the Olare Orok River, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender tracked one young leopard’s learning curve.

LENDER: The Cat in the Spotted Coat is awake.

He Strrrrretches.

And Rrrrrrises.

And opens his mouth.

Wide.

So the long canine teeth show.

A comfortable yawn that ends with that little cat hiss in his breath as the jaws click shut. All the while, walking, along, the irregular lip of the gorge.

He sniffs the ground (eyes closed) and sees, displayed on the screen of his mind, things no human mind’s eye has ever seen:

A young leopard sighted in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Who and What came this way and When in the dimension of Time. And by a lingering trace of sweat and the odor of the skin, how thirsty they were. Several paces further on he stops again, at a scuffmark in the dust, looking, taking note. Here that Very Same Animal went into the ravine. Cat recalls the water hole along the direction of the creature’s travel. Ah. Yes. A place to wait some hours from now as the darkness pours in. On he goes, all the while gaining in knowledge and experience.

For this Young Leopard there is still learning to do and the growing up that goes with it.

Now in a clump of long grass he finds where one of his own kind has left their deliberate mark. Which holds his full attention. Inhaling like a Sommelier high against the palate he discerns, terroir, the maker’s finesse, and whether ready and good or not yet prime. And other things unimaginable to you.

He licks his lips.

He licks between his toes.

Then follows the slope to the bottom.

And across.

And up the other side.

And pads along through the dried-out brush onto the flat of rust and plumb colored granite of the outcrop.

And sits.

Right in front of me.

Cat in the Spotted Coat wraps his tail around his soft cat feet and looks about. Lies down. Rolls over on his back. Yawns his Big Cat Yawn and looks at me upside down. “Pet me. Stroke my head. Scrrrrratch behind my ears. Rub my belly and I’ll purrrrrrr for you. Pay no attention to the equipment behind the curtain of my velvet black lips. Ignorrrrrre the razors called claws at the end of my paws, I only want - ”

A young leopard yawning as he treks through dry brush in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Cat in the Spotted Coat is suddenly transfixed:

Blue wildebeest, two knots of three at less than a hundred yards.

He stands, and shrugs low and in that stealthy cat walk pours himself underneath my truck. To watch. To plan his imagined SNEAKATTACK!

Tail… Swishing…

While the blue wildebeest turn their heads. And stare right back. The forward posture and their ready gaze making unmistakable reply:

“Who do you think YOU’RE kidding!”

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- About Destination Wildlife

- Read Mark's Field Note on this essay

[MUSIC: Cedo, Karun, Nyashinski “Imagination (feat. Nyashinski & Karun)” on Ceduction, Ziiki Media]

Saving Big Forests to Save The Planet

John Reid and Thomas Lovejoy’s 2022 book “Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet” (Photo: Courtesy of W. W. Norton)

CURWOOD: Some proposals for mitigating the climate crisis require huge societal changes or unproven technological innovations. But protecting the remaining intact big forests on Earth is by comparison a bargain. The new book “Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet”, coauthored by economist John Reid and the late ecologist Tom Lovejoy, puts a spotlight on these so called “megaforests”. Thomas Eugene Lovejoy III passed away in December 2021 and we remembered his huge contributions to conservation on this show earlier this year. And although he’s gone from this world, Tom continues to teach us how to take care of it. I spoke with his coauthor John Reid about these forests and the opportunity they present in mitigating climate change.

John, welcome to Living on Earth.

Thomas Lovejoy’s work in the Amazon rainforest showed that large intact forests sequester more carbon more stably and with more resilience than fragmented forests (Photo: Neil Palmer/CIAT, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

REID: Thank you so much, Steve. It's an honor to be here.

CURWOOD: Your book is all about megaforests. What exactly is a megaforest? And how many of them are there? And where do we find them on the planet?

The island of New Guinea is home to 39 of the world’s 42 species of birds of paradise (Photo: Richarderari, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

REID: So, the term “megaforest”, we use to describe five forests that are still with us here on planet Earth. And the characteristics of these forests, first of all, that they're big, they're continental in scale, and that a good part of those forests is still intact in pieces of at least 500 square kilometers. There are three tropical forests: the Amazon, the Congo, and the island of New Guinea, and then two boreal forests: the forest that covers a good part of the state of Alaska, and then goes all the way across northern Canada, just below the the tundra zone, and the Russian Taiga, which is a forest that spreads from the Bering and Pacific sea coast of Russia, all the way across the continent to Scandinavia. And this used to be just one boreal forest at certain times when the sea level was low enough to expose the Bering Land Bridge, so you see remarkable similarities between the organisms that are on both sides of the Pacific in these boreal forests.

CURWOOD: What, between the caribou and the reindeer?

REID: Yeah, and you see grizzly bears and what they just call brown bears in Russia. There were bison roaming on both sides, and of course, the human beings used that geography to move back and forth between the Americas and the Eurasian continent.

CURWOOD: John, what makes these megaforests different from each other?

John Reid is the co-author of “Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet”. (Photo: Courtesy of W. W. Norton)

REID: First of all, we have a difference between the boreal forests and the tropical forests. And this is what you would expect, the boreal forests are cold and the tropical forests are hot and steamy. The tropical forests have an incredible diversity of plants and animals, and the boreal forests have less diversity, but they have, in general, larger organisms like grizzly bears and polar bears, caribou.

CURWOOD: The tropical forests, what differences do you see there?

New Guinea is on the same tectonic plate as Australia and has many related species, such as the tree kangaroo (Photo: Shebalso, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

REID: Well, the tropical forests are very different from one another. The Amazon, if you walk around in the Amazon, you'll see a profusion of palm trees and of vines. If you cross the Atlantic to the Congo, you have massive animals. So you have forest elephants and you have three different species of gorillas, you have chimpanzees, you have bonobos, you have large ungulates. Now go over to New Guinea, you have a whole different array of species there. New Guinea is the world's capital for birds of paradise. There are 39 of the globe's 42 species of birds of paradise. You have species that look like they belong in Australia. One night, I was walking through the forest with a local guy and we came upon a kangaroo. And in the middle of a tropical forest in the New Guinea night, this thing looked, to me, so out of place, but it's because New Guinea is on the same tectonic plate as Australia and has been separated from the Australian mainland for a short enough period of time that many of the families of plants and animals that you find in New Guinea have Australian counterparts, even though the species have had a long enough time to diverge and create novel life forms there.

CURWOOD: Now, John, why is it so important to protect these few huge expanses of undisturbed forest instead of lots of smaller forested areas?

Unlike the Amazon, the Congo is home to massive animals such as elephants, which are vulnerable to the bushmeat trade and illegal poaching for ivory (Photo: Thomas Breuer, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

REID: Well, there are, I think, three things that I would point to. First of all, those places that haven't been carved up by roads, or carved up by industrial development, and settlements, or industrial agriculture, have ecological functions that are absent in forests that have been fragmented, and not just ecological functions, but climate functions. These are places that are storing more carbon, more stably, with more resilience than the fragmented forests in our world. And Tom's early research in the Amazon really demonstrated very graphically why this happens. His project created forest fragments in the Amazon in an area that was being actively deforested, and he made agreements with ranchers to leave plots of land with forest. And so what his scientific team observed over time is that those forest edges dried out, the wind knocked trees down, and there were species that were important to regenerating trees that couldn't survive in that environment anymore. The second thing I wanted to mention really has more to do with people. And our earth is still blessed with incredible forest-based cultures with human beings who grew up in the forest, whose languages emerged from the forest, whose livelihoods are tied to the forest, whose spirituality is linked to the forest. And those cultures need large forest areas in order to thrive, not just to have access to the resources that they need to thrive, but also to have some insulation from the homogenizing power of our surrounding society. The third reason that we really focus on this has to do with irreversibility. Once an ecosystem is fragmented by a road, for example, that intactness is hard to get back, and the species that are dependent on the intactness and the cultures and languages that are dependent on the intactness are impossible to get back. So that's where some of the urgency of protecting these places in particular comes from.

The Russian Taiga is experiencing a large increase in wildfires that has been linked to the development of roads (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Writing about deforestation and forest degradation, you talk a lot about roads. Why does building roads in intact forests have such a large and wide-ranging spectrum of damage and why, as you talk about in the book, does this not make much economic sense?

REID: Well, I've been studying roads in tropical forests since the mid 90s and, almost without exception, found that remote roads in intact forests don't pencil out financially in terms of the transportation benefits justifying the expense of putting the asphalt down and taking care of it. And that's just because there isn't enough economic activity there and users to justify having a fancy road. You do have people using it. First of all, the first to come are loggers. And then you'll have small farmers, subsistence farmers, who come and clear plots of land beside the road. And then after them will often come a larger farmer or land speculator who will buy up small farms, clear the area for cattle pasture. So in South America, in particular, this has been a progression that we've just seen over and over and over again. And to build a road in a tropical forest today and expect something different just doesn't really make much sense. Now, in the other forests around the world, even the tropical forests, you haven't seen the same dynamic of dramatic deforestation following roads. What you have seen, for example, in the Congo, is dramatic increases in hunting pressure. So you have species such as forest elephants, the poaching goes up dramatically, the poaching of primate species, of just the range of species that are targeted for bushmeat. The boreal forest, the roads are often associated, particularly in the Russian Taiga, with new sources of fire ignition. Fire is a huge problem across the Taiga. Over in Canada, you have species like caribou that are extremely sensitive to the presence of roads, often won't cross roads, and when roads are put in, the areas that they have as their refuges when the mothers, for example, are nursing their calves, become too small for them to be viable areas. And it's not only the humans who are going out there hunting them, but wolves use roads as hunting trails as well and put so much pressure on the caribou that wildlife managers in Canada then have to decide whether or not to go out and shoot the wolves. And sometimes they do.

Some species, such as caribou are especially sensitive to the development of roads (Photo: Craig McCaa, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So much of the commercial global north is interested in making money over the short term: gold, oil, gas. How do we start using economics to convince decision makers in these northern and rich countries to protect the intact natural landscapes that you say are really worth saving?

REID: Well, I think a good start, Steve, would be a more responsible news media. When you read the business news, you'll see reporting about the housing sector, the energy sector, the transportation sector, without any comment whatsoever on the climate implications of growth or retrenchment in those sectors, and we have to begin to recognize that everything we do has climate impacts, and the kind of economy that we want, the kind of growth that we want, the kind of energy prices we want, have everything to do with the climate we're going to get. And the truth of the matter is that we have to do everything to get to the kind of climate that we can live with that will permit a vibrant beautiful, interesting, livable world. So do we need to save our megaforests? Yes. Do we need to replant forests? We have to do that also. And do we have to address our fossil fuel problem? We have to do that too. But to protect the intact forests around the world doesn't require any technological innovations, and so a lot of the economists who have looked at this make the point that over the long term, we need to make all kinds of transformations in the way we live, in the short term, stopping deforestation is something we can do right away.

Wolves use roads as hunting trails, putting pressure on prey species, leaving wildlife managers with difficult decisions (Photo: Jacob W. Frank, National Park Service, Flickr, public domain)

CURWOOD: This book, I think, is required reading for anybody who is really looking for practical, affordable solutions to take on the climate crisis. And the book is called "Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet", written by John Reid, our guest, and by the late Thomas Lovejoy. John Reid, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

The late Thomas Lovejoy co-authored “Ever Green: Saving Big Forests to Save the Planet”. (Photo: Courtesy of W. W. Norton)

REID: It's been my pleasure, Steve, thank you so much.

Related links:

- Read about the book here

- [Find the book “Ever Green” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores]

- Remembering Thomas Lovejoy

- Listen to LOE’s 2010 interview with Thomas Lovejoy on saving the world’s biodiversity

[MUSIC: A Sound for You, “Sky” Single, Root Note Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Kharishar Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashley Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination: Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth