May 7, 2021

Air Date: May 7, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Fixing America’s Water Crises

View the page for this story

In a bipartisan vote of 89 to 2 the U.S. Senate recently approved $35 billion in funding to address the public health hazards of lead pipes and overflowing wastewater. John Rumpler, the Clean Water Program Director and Senior Attorney at Environment America, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about why water infrastructure improvements are long overdue and where the money would be spent. (09:26)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood discuss how wildlife bridges over busy highways are keeping reindeer and other migrating species safe. They then touch on the problem of discarded masks and other PPE plastics polluting the planet during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, in the history calendar they reflect back to the 1973 release of the film Soylent Green, which takes place in a dystopian New York City ravaged by pollution, overpopulation and climate change. (04:23)

Young Climate Activists

/ Annie RopeikView the page for this story

Teens and kids will be more impacted by global warming compared to older generations, and climate disruption is already bringing shorter winters with less snow and rising seas that threaten coastal areas. Annie Ropeik of New Hampshire Public Radio reports on the young climate activists in the Granite State who are organizing and speaking up for a livable future. (06:35)

Gardening for Abundance and Generosity

View the page for this story

As the weather warms at her New England home, Host Bobby Bascomb catches up with landscape designer Michael Weishan for some tips for gardens in her region as well as some general advice for gardening newcomers and aficionados all over the US. Their chat looks forward to tending to what's growing in window boxes, raised beds, and greenhouses, and how gardening fosters a spirit of generosity. (10:46)

Secrets of the Whales

View the page for this story

On Earth Day 2021, National Geographic released Secrets of the Whales, a video documentary miniseries that seeks to unravel the secrets of whale behavior and understand whale cultures of orcas, humpbacks, narwhals, belugas, and sperm whales. National Geographic Explorer and wildlife photographer Brian Skerry joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about the experience of filming this epic project and the breathtaking complexity of whale societies across the world. (16:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210507 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: John Rumpler, Brian Skerry, Michael Weishan

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Annie Ropeik

THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

A bipartisan vote in the United States Senate approves money to "get the lead out" of drinking water infrastructure.

RUMPLER: I just think there are certain things that are non-negotiable, and here in the 21st century in the United States of America, our drinking water should not be laced with a potent neurotoxin that impairs the way our children learn, behave, and grow. It's just not acceptable.

BASCOMB: Also, our gardening guru has some tips to save money and reduce the carbon footprint of gardening this spring.

WEISHAN: I am a huge proponent of growing things from seeds because of the carbon cost involved. Growing your own really cuts a huge amount of the oil and gas out of the process, so anything that you can grow yourself, as a money saving thing, as a planet saving thing, it's really great to grow seeds.

BASCOMB: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Fixing America’s Water Crises

A voluntary lead testing program in Massachusetts schools found that 50% of the faucets and fountains tested had lead, a neurotoxin that damages children’s brains even at low levels, in the water. (Photo: Jeff, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

In a bipartisan vote of 89 to 2 the U.S. Senate recently approved $35 billion in funding for water infrastructure to address growing problems such as lead pipes and wastewater. The bill would remove lead pipes from schools and low income households and would help make drinking water systems more resilient to extreme weather events and climate change. There’s also a provision to provide funding for tribal water systems as Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack plumbing compared to most white households. For more on how the money would be spent I’m joined now by John Rumpler. John is the Clean Water Program Director and Senior Attorney at Environment America. Welcome to Living on Earth, John.

RUMPLER: Thanks for having me here.

BASCOMB: What is the scale of the problem of lead in water in the United States?

RUMPLER: Wow, there are a few ways that we can measure that, Bobby; one way is to look at the number of these lead pipes, these lead service lines. These are the pipes that go from the water main in the street into your home, or into a small business, or a childcare facility. There are an estimated 9 million of those pipes, a little bit more than 9 million, EPA estimates. Those pipes are the single largest source of lead contamination in the homes that have them, according to EPA field tests that have been done. But we even have lead in our schools' water delivery systems, in the plumbing, in the fountains, in the faucets. And we know that lead is harmful to kids, even at very low levels. Now to just give you an idea of how widespread the problem is, here in Massachusetts, the state has done a wonderful job with a voluntary lead testing program for schools. The data are alarming: they show that nearly 50% of the faucets and fountains tested had lead in the water. Our affiliates in Washington, and Texas, and Montana, and New Jersey, and other states have found similar levels of contamination in our kids' schools.

Lead service lines feed into an estimated 9 million homes, small businesses and childcare facilities in the United States. (Photo: IntangibleArts, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow. And lead, of course, is toxic to anyone, but it's especially troubling for children.

RUMPLER: That's exactly right. Which is why the CDC, the World Health Organization, EPA, virtually every public health authority on the planet has said there is no confirmed safe level of lead. Even at very low levels, 24 million kids here in the US are right now at risk of losing IQ points due to exposure to low levels of lead. Now, not all of that comes from water, of course, there's other sources of lead contamination. But geez, we should not be having lead in the water where our kids go to learn and play every day at school.

BASCOMB: Now, this vote passed the Senate 89 to 2. That seems extraordinary in this climate of hyper partisanship in Congress! To what degree do you think that this vote is saying something about the universal nature of this problem of unsafe water in the country?

RUMPLER: Bobby, I think that's exactly what it's saying. And it's pretty clear why a bill like this would garner such incredible support in the Senate. So let's take Senator Capito from West Virginia. In West Virginia, in addition to the typical problems we have of lead in drinking water and sewage overflows, it turns out that there are so many old leaky pipes that drinking water utilities are losing 55% of the water that they treat and pump before it gets to people's kitchen sinks. That's just an incredible waste of water and money. So you can understand why a senator from West Virginia would want to invest in fixing those old leaky pipes, so that we can actually have clean water that's affordable and safe for all the people of West Virginia.

BASCOMB: Well, let's dig into some of the details in this bill. How exactly does it address the problem of toxic lead in water?

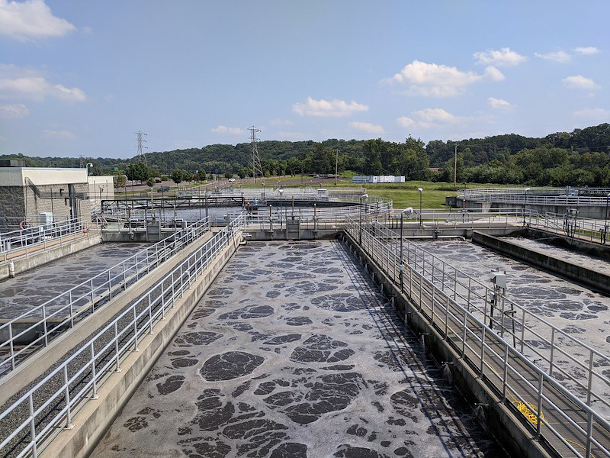

The Oaks Wastewater Treatment Plant in southeastern Pennsylvania (Photo: Montgomery County Planning Commission, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

RUMPLER: Sure. The Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Act of 2021, with the dubious acronym "DWWIA," is the bill that we're talking about here. And it makes some important improvements in addressing the issue of lead in drinking water. First, it does increase the funding levels for two key programs. One is an EPA program that deals with these lead pipes, so-called lead service lines, increases the funding for that program, to $100 million per year. The second thing is that in terms of dealing with lead in our schools, it provides a total of $200 million over the next five years to deal with lead in schools. But to my mind, even more important than these increases in funding, which are not enough to solve the problems but they're a good step forward, are the actual policy changes in how these programs work. So for example, up until this bill, the primary program that EPA has for schools to receive grant funding for lead in drinking water would only allow the schools to use that money for testing. But Bobby, we have more than enough testing. We have tens of thousands of tests, already confirming widespread contamination of our schools' drinking water. What school boards and superintendents across the country need is money to actually get the lead out, to replace fountains and faucets that have lead in them, to install new filtration systems. That costs money, and the good news is that this bill, DWWIA, will now allow school officials to use that federal funding to actually solve the problem, instead of just running tests to confirm that yes, indeed, our kids are drinking water laced with a potent neurotoxin.

BASCOMB: John, so let's shift gears and talk a bit about wastewater, which this bill also plans to address. What's going on with the wastewater infrastructure in the United States?

A sign at Waikiki Beach in Honolulu, Hawaii warns would-be swimmers of sewage contamination. (Photo: Keith-H, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

RUMPLER: You know, about 50 years ago, we made a commitment through the Clean Water Act as a nation to ensure that all of our waterways would be safe for swimming. And yet, last February, when I testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on the Environment on water infrastructure needs, while I was testifying, there was a sewage treatment plant in Nebraska that had been inundated with flooding, and as a result had been pouring up to a million gallons of untreated sewage into the Missouri River every day for months on end. Earlier this year, we saw sewage overflows in the greater Miami area, where of course beaches and swimming are a crucial part of our quality of life as well as the economy there. We've seen sewage overflows really pretty much everywhere: the Great Lakes, the East Coast, the South, everywhere. We did a report last summer and we'll do another one this summer called Safe for Swimming, where we looked at the fecal coliform testing data from beaches all across the country. And we found half of the beaches unsafe on at least one day per year. One in eight beaches were potentially unsafe 25% of the time. Public health experts estimate that there are 57 million instances of people getting sick because of being in contact with water, swimming, paddling, canoeing, etc. every year here in the United States. That's just intolerable in the 21st century, we can do better.

BASCOMB: And so how exactly would this bill address that problem?

RUMPLER: So the main program, the main federal program for helping states and communities to address this problem is called the Clean Water State Revolving Fund. And the bill that just passed the Senate would increase that program up to $3.25 billion a year over the next five years. I should note that the need is much greater. EPA estimates that the need for addressing our wastewater and sewage overflow problems is going to be $271 billion over the next 20 years. So just doing my math, that is a lot more than $3.25 billion a year.

John Rumpler is Clean Water Program Director and Senior Attorney at Environment America. (Photo: Courtesy of John Rumpler)

In fact, overall, when you look at drinking water and wastewater together, EPA estimates a price tag of $35 billion per year for the next 20 years. The DWWIA bill that just passed the Senate authorizes a total of $35 billion over the next five years. So it's a good step in the right direction, but a lot more help is needed to ensure that we get the lead out of our drinking water, and all of our beaches are safe for swimming.

BASCOMB: John Rumpler is Clean Water Program Director and Senior Attorney at Environment America. John, thank you so much for taking this time today.

RUMPLER: My pleasure, thanks so much.

BASCOMB: As we go to broadcast the House has yet to vote on the Senate water infrastructure bill but given the bipartisan popularity of the legislation it is widely expected to pass.

Related links:

- The Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Act of 2021

- Environment America’s “Get the Lead Out” report

- Grist | “‘Long overdue’: The Senate just passed $35 billion for clean drinking water.”

- Find Environment America’s “Safe for Swimming” report

- About John Rumpler

[MUSIC: Steve Schuch, “The Hole In the Orange” on Crossing the Waters, by Steve Schuch, Boston Skyline Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Reindeer crossing a road between Luleå and Malmberget in Sweden. (Photo: Stefan Schmitz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s time for a trip Beyond the Headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and daily climate dot org. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: Hi there, Peter. How you doing today?

DYKSTRA: Hello Steve, I'm doing alright. And Sweden has made a little bit of news in the past week announcing that it's going to build a series of possibly 12 animal bridges over a busy highway. It's the latest effort to help wildlife cross busy highways without getting run over. They're putting in a dozen "renoducts", which if you're not up on your Swedish shorthand, it is shorthand for reindeer bridge. It's going up along a major highway that's crossed twice a year by migrating reindeer herds. The Sami people, the indigenous people of Scandinavia, heard huge numbers of reindeer. This will save the lives not only of reindeer who get hit. If you've ever smacked a reindeer with your car, you are at risk as well.

CURWOOD: It's quite dangerous to run into an animal like that. So where else are these, Peter? I know there's one in Canada. I think in Banff, it's almost as wide as the two lane highway itself for various animals to cross. Where else is this going on?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the Banff National Park is one of the pioneers of this in Canada. There are wildlife crossings, both bridges and tunnels in places like Southern California for mountain lions. Mexico has been successful in building overpasses and tunnels for jaguars, in the Peruvian Amazon there are passageways for monkeys and porcupines as well. Those wildlife crossings and wildlife corridors, not only save animals and occasionally save human lives, but when an animal gets down to low numbers like the Florida Panther, it helps save the species in another way. Because if there are so few to reproduce, when they are able to reproduce, you want some genetic diversity by having more animals.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the ability for animals to move around safely. Hey, Peter, what else do you have for us today?

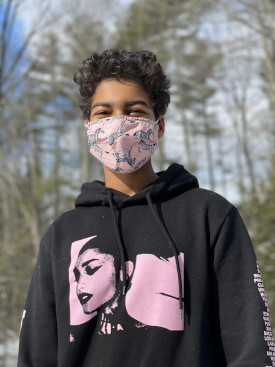

As the use of face masks, gloves and other PPE has exploded during the pandemic, litter is a grave concern for wildlife. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Something that we didn't realize was ever going to be a problem, an offshoot of the global pandemic. And that's that face masks are everywhere, including on the ground, in the sewers, in the waters, in the landfills and everywhere else. Those face masks and other personal protective equipment we never gave much thought to, for the most part is made of plastic, mainly polypropylene. It's everywhere on Earth. It's even getting into the oceans.

CURWOOD: You know, when I walk around, it's not unusual to see one of these on the ground.

DYKSTRA: Masks are everywhere. You've also got gloves, sanitary wipes, all sorts of things like that. They're also mistaken by wildlife for other things. There's a bird in Europe called the common Coot. And in the Netherlands, it's been observed picking up face masks in order to build nests.

CURWOOD: Well, that's one way to reuse them anyway, I hope it's safe for the Coots. Hey, Peter, let's take a look back in history now, tell me what you are seeing.

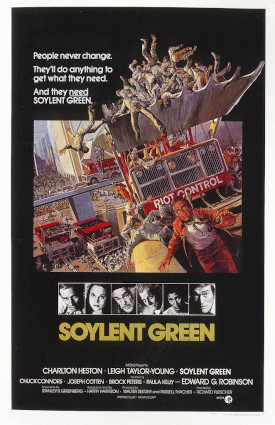

DYKSTRA: May 19th, 1973, a movie called Soylent Green was released. The title refers to what the violent desperate people of New York City are fed. And this all takes place in the far off year of 2022.

Released in 1973, Soylent Green takes place in a dystopian New York City in the year 2022, where overpopulation, pollution and climate change have created huge shortages of food, water, and housing. (Photo: Huysamen Engelbrecht via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: All right, we're gonna play a little clip from that movie right now.

HESTON: You tell everybody... Listen to me, Hatcher. You're gonna tell 'em! Soylent Green is people! We gotta stop 'em, somehow!

CURWOOD: Huh, Soylent Green is people! So why are people eating people in the year 2022 in New York City?

DYKSTRA: There are so many problems that have in this movie cropped up by then, overpopulation is one, pollution is another, and early mentions of climate change in 1973.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. We will talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you very much, Steve. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: That’s Peter Dykstra speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and daily climate dot org. And there’s more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “How Creating Wildlife Crossings Can Help Reindeer, Bears – And Even Crabs”

- National Geographic | “How to Stop Discarded Face Masks from Polluting the Planet”

[MUSIC: Edgar Meyer, “Interlude #1” on Edgar Meyer, by Edgar Meyer, Sony Classical]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Children and climate activism. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Butterfat Trio “ My Not Dink” on Under the Dog, Hi Lo Records 2004]

Young Climate Activists

Azalea Morgan, 9, (left) and her sister Ember Morgan, 10 (right) stand with their bikes on the porch of their home in Andover, New Hampshire. The sisters biked to New York City from Andover with their mom to raise awareness about climate change in 2019. (Photo: Ryan Caron King, Connecticut Public for the New England News Collaborative)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

By the time today's teenagers turn 50, much of the world’s climate will feel very different. Under current warming trends, colder climates are already seeing shorter winters with less snow. And many coastal areas are dealing with rising seas that can amplify storm surges. Without swift action to stop fossil fuel emissions it could get much worse. This possible future is calling more and more young people to act and they're getting results. New Hampshire public radio reporter Annie Ropeik has this story about children in the granite state taking action.

ROPEIK: Ember and Azalea Morgan of Andover remember where they were when they first realized what climate change was doing and would do to their planet.

AZALEA: We were at a friend's house for a party, dinner, thing, blah blah blah. And we were watching TV, National Geographic, I think, and I saw this video about, like, polar bears and global warming and how the ice is melting and they don't have a lot of ice left. And I got really sad.

ROPEIK: That's Azalea she's nine and Amber is 10. Scientists say the world has about until these sisters are in college to prevent the worst effects of climate change. That night, Molly Morgan, the girl's mom, remembers what happened at bedtime.

Molly Morgan, center, sits with her two daughters, Azalea, 9, (left) and Ember, 10, (right) on the porch of their home in Andover, New Hampshire. They started a climate activism group, Kids Care 4 Polar Bears, that's raising money to install solar panels on their school. (Photo: Ryan Caron King, Connecticut Public for the New England News Collaborative)

MORGAN: I had a moment with Azalea in her bed when she was just sobbing uncontrollably, like almost like I'd never heard her sob before. And for me to have my own child be cognizant of these climate issues and mass extinction on our planet it just really hit home to me.

AZALEA: And then my mom was like ok, we will do something. I promise you. I don't know what, but we will do something.

ROPEIK: This was in 2019, just days before a major climate summit in New York. Then-16-year-old Greta Thunberg, now a household name, was sailing there across the Atlantic to raise awareness about climate change. It gave the Morgans an idea: to pack up and bike all the way to New York from their home in Andover, New Hampshire to be part of the moment.

MORGAN: It certainly was empowering, especially having those girls peddling their little legs on these tiny bicycle wheels hundreds of miles, really, it was phenomenal.

ROPEIK: Azalea says it surprised some adults that she and her sister were so invested in this at such a young age.

AZALEA: Some people are like, 'Well, we're not going to be alive to see it,'" And we're like, well, it's my future. I should decide what's good for our future.

ROPEIK: When that future arrives, if adults don't take more action now, scientists say Azalea and Ember will live on a planet plagued by more extreme heat, floods, droughts, wildfires and storms, and all the inequality, health and social problems they’ll cause. With that in mind, the sisters have kept up their climate activism -- raising money for solar panels at their school, going vegetarian and encouraging classmates to recycle. Ember ran for New Hampshire kid governor on a climate platform. They're part of a corps of youth climate activists that's growing exponentially across the state.

Youth climate organizer Lydia Hansberry, 15, picked up trash in Hanover for Earth Day in 2020. (Photo: Courtesy Lydia Hansberry via NHPR)

CHAVDA: Hi I’m Nikhil Chavda I live in Nottingham, New Hampshire and I’m 14.

HANSBERRY: I’m Lydia Hansberry. I live in Hanover, New Hampshire and I’m 15.

ROPEIK: Like the Morgan sisters Lydia and Nikhil say they’ve been worried about the environment for a long time. Lydia remembers first learning about the ozone hole when she was in fifth grade.

HANSBERRY: I kind of thought it's like it sounds kind of childish, but it's not fair. Like, how can we be so careless with our home and how can we just destroy it in this way?

ROPEIK: Last year, Lydia was on a Zoom call to hear about the launch of a new climate justice campaign in New Hampshire. A student organizer sent her a chat, asking if she wanted to join a youth program with the activist group 350 New Hampshire, it’s a chapter of the left-leaning nonprofit started by Vermont environmentalist Bill McKibben. Groups like 350NH are giving more young activists like Lydia an outlet for their climate anxiety.

Nikhil Chavda, 14 and from Nottingham, is a youth fellow with 350NH. (Photo: Courtesy Nikhil Chavda via NHPR)

HANSBERRY: It's kind of knowing what scares you but also knowing that there is the potential to fix it.

ROPEIK: Nikhil was recruited by a friend and classmate to join 350. He says being part of a group of other activists mostly led by people in their late teens and 20s has been vital while he's still too young to vote, or drive himself to protests.

CHAVDA: It's hard to get taken seriously when you're 14. In terms of things like asking our representatives and senators to sign bills, they don't really think of us as voters of the future. They think of us as kids.

ROPEIK: Nikhil has found he and his peers can have an impact through climate strikes, raising awareness on social media, and getting out the vote for progressive candidates who support strong climate action.

CHAVDA: New Hampshire is, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful states in the country, and I want to preserve that. I want to keep temperatures down, I want to keep lakes full without drought, and I don't want sea level rise. I just want things to stay as perfect as it is right now.

ROPEIK: Nikhil says he’s learned to emphasize New Hampshire's beauty when he talks climate policy with adults, including state legislators. He hopes to run for state office himself one day. Some young climate activists are already seeing policy results. The ECO club, at Portsmouth High School helped push for a city-wide ban on Styrofoam and some other single-use plastics. But right before it was set to take effect in late 2020, the city council wanted to postpone it because of COVID-19. Abby Herrholz is a senior at Portsmouth high and the Eco club co-president. I reached her by zoom at a noisy coffee shop, she didn't have good wifi at home.

HERRHOLZ: I was really angry. I was like, this is unacceptable. We need to figure something else out.

ROPEIK: So in spite of the pandemic and remote school, Abby and her classmates mobilized.

Climate activist and high school senior Abbey Herrholz stands for a portrait in Prescott Park in Portsmouth. Herrholz helped lead a grassroots campaign in her city to ban single-use plastics and styrofoam. (Photo: Ryan Caron King, Connecticut Public for the New England News Collaborative)

HERRHOLZ: Again, we went to the city council, we wrote letters, we reached out. And again, we brought the youth front to be like, this is our future, not all about you. And we ended up changing the minds of three or four city council members, and now the ban is in effect.

ROPEIK: Portsmouth's plastics ban is the first local ordinance of its kind in the state. All these young activists had the same advice for people their age on how to turn their fears about climate change into action. Here’s 10 year old Ember Morgan.

MORGAN: Just do it. You don't need anything. You've just got to start.

ROPEIK: They say we all have more power than we think.

BASCOMB: Annie Ropeik’s story comes to us courtesy of NHPR’s By Degrees climate reporting project. You can see more of their stories at nhpr.org/climate.

Related links:

- NHPR | "'It's My Future: A New Generation Of Young Climate Activists Takes The Helm In New Hampshire”

- Learn more about the climate youth organizing program 350 New Hampshire

- Learn more about Ember and Azalea’s fundraiser to make their school run on 100% renewable energy by 2030

[MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Marcia Ball, “Pinetop’s New Boogie Woogie” on Ladies Man, by Perkins, M.C. Records]

Gardening for Abundance and Generosity

As the weather warms, gardening newcomers and aficionados alike look forward to what will be growing. (Photo: Hans Splinter, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: For many northern gardeners, like me, spring means we are counting down the days till Memorial Day when the danger of frost has finally passed and we can get planting. So, it seems like a good time to check in with our resident gardening guru Michael Weishan. Michael is a landscape designer, veteran of Living on Earth, and former host of the Victory Garden on PBS. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth!

WEISHAN: I am delighted to be back. Happy spring,

BASCOMB: Happy spring. It's May and a few weeks till our last frost here in New England, when it's safe to plant outside. What are you up to right now in the garden, though?

WEISHAN: You know, this week is supposed to be pretty rainy. So I'm going to be in the greenhouse working with seeds. And that's one of the things I wanted to talk with you guys about today for various reasons. One of which is that I'm a huge proponent of growing things from seeds, because of the carbon cost involved. Growing your own really cuts a huge amount of the oil and gas out of the process. So anything that you can grow yourself, you're not only going to save a ton of money, because Bobby, if you've been to the nursery lately -

BASCOMB: I have.

WEISHAN: - you'll know where the prices have gone. It's just incredible. So as a money saving thing, as a planet saving thing. It's really great to grow seeds. But what's really great about it to me is that you get to try things that you would normally not get a chance to try or you won't see in the stores. So I've actually just pulled a number of packets here today to talk about some of the fun things that I'm going to grow. And that some of our listeners may want to grow as well. And that, by and large, there's still time to do. So which one of these wonderful things do you want to start with? Because I'm excited to talk about all of them.

Chinese Red Meat Radish, also known as “watermelon radish” are known for their bright, rose-red center. (Photo: Quinn Dombrowski, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Oh, well, I don't know, alphabetical or your favorite, you decide.

WEISHAN: Alright, so I'm going to start with this one. Radish. Chinese Red Meat is a type of daikon. It's called "watermelon radish" as a nickname. And I think it's absolutely fantastic slightly pickled. I've grown this last year, I'm going to grow this again. Kids love it because it is this bright red color inside, it is absolutely fantastic looking. And it's really super easy to grow. It's to just kind of plant and push and they pop up. The seeds are widely available through mail order. And if you like something a little spicy - are you spicy person, Bobby?

BASCOMB: Somewhat, somewhat, you know, I have to say though, I've had very little success with radish. Maybe I tried them too early? Maybe this is the time I was probably you know -

WEISHAN: No, this is the time because they're cool weather plants generally. Generally they, the problem is that they don't go well in cold weather. This one however, this daikon actually is sown later in the season. So that's one of the reasons I wanted to talk about it today. Planting instructions: plant in late summer for harvest after the winter begins to cool. So you know, we've got quite a time to go in front of that.

BASCOMB: Yeah, sure.

WEISHAN: I want to talk also about broccoli rapini. Now do you know rapini?

BASCOMB: I think I've had it before, I've certainly never tried to grow it though.

WEISHAN: Well, I have terrible luck growing broccoli because the moths get into the heads and the head split, and I don't know, it just, I've had terrible time. So I've not been a successful broccoli grower. So I'm going to try this. It's an Italian non heading broccoli, grown for the flavorful - I'm reading from the packet - asparagus-like spring shoots and leaves. It's planted now and and cool weather and it should be fairly fast growing. So I would expect to harvest in about 60 days or so.

BASCOMB: Wow.

Rapini, also known as broccoli rabe, is a popular ingredient in many Mediterranean cuisines. (Photo: Dana McMahan, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

WEISHAN: So we'll see.

BASCOMB: That's really quick.

WEISHAN: Great salad, you know, great, great cooked vegetable kind of thing.

BASCOMB: Now, do you save seeds as well in the fall from your own plants?

WEISHAN: Well, no. And I'll tell you why. Because we grow a lot of hybrids. And obviously you have to start afresh with hybrid seed. I'll tell you a funny story though. I have been friends since my Victory Garden days with Amy Goldman who's a well known horticulturist in from New York who has produced wonderful books on tomatoes and squash, and just an incredible horticulturist. As a matter of fact, she has a tomato named after her. "Green Doctors" is named after Dr. Amy Goldman and one of her research companions. So she's been a friend of mine since the Victory Garden days. And she came and brought one time to film these incredible round bottle gourds. And they are perfectly round. I have a whole set on one of my shelves that she left with me. It's a big papa gourd, which is a perfectly rounded, you know, foot and a half and mama and then three little trailing children. And I've used them for decorations for years and I called Amy up. I said, do you still have the seeds for this? And she said, no, I don't. And they seem to have passed out of production. I said, do you think those seeds are still viable? In that gourd? Now, we filmed this in 2003. So you know, this is 18 years sitting in that gourd? She said, yeah, I think so. I think they would probably go if you gave them a little soaking and tender loving care. So I carefully drilled a hole about a week and a half ago in the bottom of this gourd and there were hundreds of seeds in there. And so now they're in the greenhouse, I've soaked them. And I'm waiting to see the result. I don't know but I tell you this will reaffirm my faith in God, or at least the gardening God, if these things sprout after sitting on my shelf for 18 years, granted in an airtight container, but nonetheless, I think that is just a remarkable destiny story if it works, so stay tuned, listeners.

BASCOMB: You'll have to come back in a couple months and tell us how that panned out if they germinated for you or not. Well, you know I have a story for you actually, a friend of mine recently gave me a couple of dried up marigold flowers from her garden. And each flower holds, you know, dozens of seeds. She got them from her mom who's been saving the seeds from the same plant since the 1970s and she originally planted these, I think she calls them cinnamon marigolds, because the red color of the flower was the same color as her baby daughter's hair. She's a redhead. And so she's been growing them every year, saving the seeds every year, re-planting them. And now the friend that gave them to me is that baby daughter all grown up. And I just love that, you know, I love those types of stories.

Iris, like the ones that Michael Weishan grew with his grandfather, will bloom in the spring and summer months. (Photo: Linda Tanner, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WEISHAN: I have a number of plants that have been passed down to me, I have a wonderful potted begonia of a extremely archaic type that I don't even know what it is, that is well over 120 years old. It came down to a friend of mine, who's now passed away a number of years ago, in her 80s. And she got it from her grandfather, so probably around 1870 or so. And I think of her every time it blooms, it's just it's, it's it's a wonderful tuberous type, begonia. And we were talking earlier about what I was, what I was doing. Just before we came on air here, I was out digging up iris, those iris are some direct descendants of my grandfather's iris that I grew up with. That's how I learned gardening. He was a fairly well noted hybridizer and hugely interested in iris and day lilies. And that's how I cut my gardening teeth. So some of those are the actual plants or descendants thereof, that were growing in his garden. And every time they bloom, which is going to be in a couple of weeks' time, they put on a spectacular show, really unrivaled I think in the gardening world. And I'm once again back on South 27th Street in Milwaukee in those wonderful May days with my grandfather. So I am a huge advocate of heirloom plants, not in the heirloom sense of old varieties, but in actually passing things down along to other people that care about them.

BASCOMB: Yeah, exactly. And, you know, I love these stories, you know, I love the idea that every plant has a story and that you can trace its roots, you know, pardon the pun, back so far. You know, it's something I've gotten really into in the last year are there's so many different Facebook groups that are local to where you are, at least local to where I am. And I assume this is true across the country of you know, sharing plants, swapping perennials, or if you just have a group of gardening friends, inevitably, you have too many zucchini seeds and not enough tomatoes or whatever. It's wonderful just to have a group of people that you can share resources with and not have to buy more.

WEISHAN: Absolutely, you know, interestingly, as a product of COVID. And this is a very bizarre, you know, alignment. The number of people, obviously, that I see dropped precipitously during the last year. But within our small little group, we're all fairly avid gardeners. So we started to split up the growing responsibilities for a lot of the plants we started. Now, I happen to have a greenhouse, I'm the only one that does, but they all have growing lights and growing spaces. So rather than, you know, go out to the stores and things we have grown a lot of this stuff ourselves and created this sort of little nursery co-op, as it were. And of course, you know, I'm gonna say this on air, my dear friend, Patty is a little plant crazed. And she's one of my chief operators in crime on this. And she insists whenever she has a packet of seeds, she has to plant the entire packet. There is no saving the seeds for Patty. You know, every child has a chance to be free, right?

Donating seeds to community gardens and produce to food banks are great ways to connect with the larger gardening community in your area. (Photo: King County Parks, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Oh, my gosh.

WEISHAN: I think she thinks of every seat as sort of like an a child in prison. So I got some coleus from her the other day, and they were in two little six packs. And each each little tiny six pack, it turns out there were like six or eight tiny little coleus. I said, Patty, you cannot plant this many seeds. "Oh, but I just I love the plants." So we have hundreds of plants leftover that we give away to friends and family and people at the community garden here we support. You know, the folks that can't grow their own. One thing also that we've started to do a lot of last year was to give away extra food to the food banks. There was and continues to be tremendous need. I know the economy is recovering and booming and stocks are booming. But the bottom quarter of the economy and of our our citizenry are still in really desperate straits. A lot of these industries have not reopened the service industries. And it's going to take years and it's entirely possible some of these jobs are never coming back. So the food banks have been doing absolutely booming, booming business for need, but not necessarily getting enough of what they actually could use. There's huge influxes of food at Thanksgiving and the holidays. But during the rest of the time, especially the summer, there's not a lot. So if you can grow extra produce and give it away, by all means.

BASCOMB: That's a wonderful idea.

WEISHAN: Well, you know, I have 18 apple trees, I'm one person right? Granted, I make a lot of cider. So during the non-COVID days, I would invite various groups, Boy Scouts or senior citizens support groups, whatever to come pick or for the food bank to come pick apples. And these trees produced, oh, I don't know, hundreds of bushels of apples. And so again, rather than having any of that wasted or composted, there's such a need for this type of stuff. Even zucchini, right? Everyone grows a thousand million zucchini. But if you don't have a garden and if you're in from the city and you are in a in a food desert, I mean these type of fresh produce for folks that don't have the ability to grow this or buy it. These are gifts from heaven. So give your produce away.

BASCOMB: Michael Weishan is a landscape designer and former host of the Victory Garden. Michael, thanks so much for joining me again today. It's been so much fun.

WEISHAN: Bobby, it is always a pleasure to talk to you and to be back here on Living on Earth.

BASCOMB: Oh, the pleasure is mine. Believe me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Michael Weishan

- Listen to our most recent segment with Michael Weishan

- Learn more about the PBS Show The Victory Garden

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Mountain Laurel” on Woodland Dance, by Joshua Messick, joshuamessick.com]

BASCOMB: Coming up – We’ll take a close look at some unique cultures among whales. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Stan Samole, “Froggie Went A Courtin’” on Childish Dreams, traditional American, Jazz Improvisation Records]

Secrets of the Whales

A mother Humpback Whale with her calf in the waters off of Rarotonga, Cook Islands along with two escort males. Humpbacks in this region spend summers feeding in Antarctica, then migrate to the South Pacific to places like the Cook Islands where they have their calves and spend time in the warm, protected waters here. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb

A new 4 part National Geographic video series, Secrets of the Whales, takes a deep dive into the culture of several whale species.

[HUMPBACK WHALE SONG]

BASCOMB: From the ever evolving song of humpback whales

[HUMPBACK WHALE SONG]

BASCOMB: To the unique way Orcas in Patagonia beach themselves to catch unsuspecting seals, or how narwhales know when to be silent to avoid predators in their migration. All of these are learned behaviors, some passed between individuals and many taught to young whales by their mothers. Brian Skerry is a National Geographic photojournalist. He spent 3 years filming the series and joins me now. Brian, welcome to Living on Earth.

Orcas in New Zealand follow a unique hunting technique: taking stingrays off the bottom - sometimes in very shallow water. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Kina Scollay)

SKERRY: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So, a theme that comes up again and again in this series is culture: that whales have distinct cultures. And not just between different species of whales, but between different pods or families. Broadly, how is culture expressed in whales?

SKERRY: Well, that is the essence of Secrets of the Whales. You're absolutely right. When I created this, I saw this as a game changer that the latest and greatest science was revealing that these charismatic ocean animals are showing behaviors that are really cultures, not unlike humans. My friend, Dr. Shane Gero, who's a sperm whale biologist, he defines it this way. He says behavior is what we do, culture is how we do it. So for example, most humans eat food with utensils, that would be behavior, but whether you use knives and forks or chopsticks, that is culture. So what we see in whales, you know, you might have a family of Orca that live in New Zealand, and their preference for ethnic food is stingrays. And they figured out how to eat those there. And the ones in the Norwegian Arctic, like to eat herring, and they figured out how to predate on herring. And the ones in Patagonia like seal pups, and they are the only ones in the world who have that strategy. They not only figured out this stuff, which is culture, but they pass it on to their children. So they are not only teaching their offspring the skills that they will need to survive, but they're teaching them their ancestral traditions, the things that matter to them. Whales have unique dialects. Sperm whales that Shane studies in the Eastern Caribbean, he's identified about 24 families that all speak the same dialect or language, and they belong to a clan. But they don't intermingle with other sperm whales that might come into those waters that speak another language. I think we can look at culture from a number of perspectives. But it's clear that like humans, they are doing things differently and what they know about their regions, their geographic location is unique to them. And that's what they celebrate.

Orca hunting rays in the waters off of the North Island in New Zealand. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: And during your time in New Zealand with orcas there, there was a moment in the series where you were invited to share in the spoils of their hunt. Can you tell us about that experience?

SKERRY: I can. This was certainly one of the most extraordinary moments of my career of four decades of exploring the ocean. We worked in 24 locations collectively for this series worldwide over three years. And I had just come from six weeks in the Canadian Arctic and I had about 10 days in New Zealand. I was working with a researcher Dr. Ingrid Visser, who is the orca expert, lives in New Zealand understands these animals. But again, you can never predict when something is going to happen. And we got lucky this one day we heard about this, we drove three hours to get there, got in the boat, went out found the orca, they were hunting in shallow water. I got in the water and started swimming towards them. And lo and behold, here is this adult female swimming towards me with a stingray actually hanging out of her mouth. My mind is on overload now, I'm thinking, I can't believe this. And then she drops it. So I'm thinking, oh man, you know, it's over.

She just gonna keep swimming. And I swim down to the bottom and I knelt on the sandy floor next to the dead stingray just laying there. And then out of the corner of my right eye, I see this orca coming back, and she swings behind my back, I lose sight of her for a moment. And then she emerges on the left side of my view, she swings around directly in front of me. And now we're staring at each other with a stingray between us. And she's looking at me and looking at the ray looking at me looking at the ray as if to say, "Well, are you going to eat that"? And when I don't go for it, then she very gently just bends over, picks it up in her mouth and lifts it up in front of me. And then she turns and begins sharing her food with another member of her family. You know, I don't think I fully processed what was occurring until after. That night over dinner, I started to think about just how remarkable that was. I talked recently with James Cameron about this. And he said, well you know, cultures do this. They share food. It's it's an offering. Very possibly that's what's going on. And you know, for me, I've had so many extraordinary moments with wildlife over the years. But this was right at the top of the list. It was really something very, very special.

National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry travels to Norway's remote fjords for a chance to capture new orca behavior. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: Yeah. And there's a cameraman right there so the viewer can watch this whole scene and you're wearing a black wetsuit. And I gotta wonder, does the orca just think you look like a skinny whale who maybe need some help?

SKERRY: Maybe, I mean, it's very possible. Who's to say? These are animals that share food, that's what they do. They catch a ray and then they turn around and one will hold it in their teeth in their mouth and another one will come over and take a piece off. So you know, I mean, it's very possible she was thinking, come on, join in the feast with us.

BASCOMB: The second part of your series is about humpback whales and you focus a lot on the sophisticated ways that they have of communicating across really vast distances. The males make up a new song each year that can travel thousands of miles. Can you tell us more about that?

SKERRY: Yeah, I call it the "American Idol" of the sea. It's a bit of a singing competition where, as you described, these males will compete every year at the beginning of the year with a tune, and then one tune gets to be the winning tune. And they adopt it and everybody sings that same song, pretty much. They might add little bits and pieces here and there, but they essentially pass it across the entire ocean. It's been described in scientific papers as the horizontal transmission of culture. Now, the interesting thing is that it's always been believed that the humpback whale song sung by the males is something to do with mating, that they are attracting females the way that a bird would attract a mate with its song. And there very well may be truth to that. But I've talked to researchers who have spent decades studying the humpback whale song, and I asked them what percentage of the time do you actually see a female come over and pair up with a male? And I forget the exact number, but it was something like 0.001%. So it doesn't get seen that often.

Humpback whales undergo one of the longest migrations of any mammal on Earth - over 6,000 miles. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Adam Geiger)

Now, might it be that the collective number of males that are singing in a given place are attracting the females to those waters, and then they can do their courtship and mating and so forth? Perhaps, but I wonder, they're creating these very lyrical, 20 minute-long songs, and to be in the water next to them and to hear it is awe inspiring. It resonates your body, and maybe a little mystical, but I wonder, is there other information encoded in that message? Might it be like an Aboriginal song line that they're including some cultural elements of that song? Is it purely just to attract a mate? Or are they weaving in stories of their ancestors? Maybe that's a little bridge too far. Maybe that's a limb that some scientists won't go out on. But the bottom line is, we've been studying these animals for decades, we don't fully understand. I think there's a lot more secrets out there that, you know, need to be revealed in the time ahead. So hopefully, we'll figure that out.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's amazing. And you know, we've been talking about male humpback whales. But I have to say, I think the females are really just as amazing. Can you talk to us please about the sacrifice they make each year when they have a calf and and the tremendous journey that they make with their babies?

SKERRY: Absolutely. You know, humpback whale mom invests a great deal into her calf. It's a year-long gestation period. And then for the first year of that life, it is learning everything that it needs to know from mom, it is joined at the hip. There up nuzzling next to its chin, and going along next to its eye, and then nursing underneath. It's such a tender moment to go out in the morning and one of these tropical locations like the Cook Islands, or Tonga, go into a quiet little Cove and then slip in the water. And just at the edge of visibility, you see this tenderness, this absolute love that's being shared by the mom and calf. And then as you say, they have to make this epic journey. There's new science that's come out just maybe in the last year or so that reveals that humpback whale moms whisper to their babies when they're traveling through areas where predators might be so they don't give away their location. So again, I think there's just so much richness to these bonds, these relationships. And again, so much of that we don't fully understand as well.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I was really struck by the fact that the mothers will feed their babies something on the order of more than 100 gallons of milk each day without eating themselves, they go for months and months without eating and are still nursing the babies just a tremendous amount of milk. It's amazing.

A group of humpbacks approach biologist Nan Hauser and National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry while on assignment for Planet of the Whales. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Hayes Baxley)

SKERRY: It is, and that's how that calf grows. But think about the impact on that mom's body. I mean, the humpback baby is gaining weight every day, but she's losing it. So by the time it's ready to make that journey, she must be exhausted, you know, she doesn't have any energy. And now she has to make this epic migration to the feeding grounds and look after her calf and protect it from predators and all of those things. So you make a good point. She is deeply invested in that next generation. And it's it's a huge sacrifice, indeed.

BASCOMB: And you can see why they're obviously so invested. You know, we've heard stories of mothers losing their babies, they die for some reason or other, and pushing them through the water for just days and days, maybe even weeks, just unable to let go. You can see why after such an investment.

SKERRY: Of course, and we've captured that in the orca episode where in the Norwegian Arctic, it was Thanksgiving Day. You know, I've been working for National Geographic for almost 25 years and I travel eight or nine months a year but this was the first time I had been away from my own family on Thanksgiving Day. So I woke up that morning and I was thinking about my family at home eating turkey and celebrating and wishing I was home, but I got on the boat with my wetsuit and we went out and we saw this family of orca moving very purposely through one of the fjords. I was able to get in the water and see this funeral procession, this mom carrying it's dead baby and all the other members of the family sort of protecting the mom and calf and, you know, you see this grief, there's no other way to interpret that I think then mourning. And it was very emotional for me to be able to see that. But clearly, these animals have empathy and share grief and joy. And I think that's the message of Secrets of the Whales is that if we can see our planet, the ocean, through the lens of culture through the lens of these animals that have rich societies, then maybe we change our view of our connection to the natural world and maybe protect this beautiful planet on which we live.

A baby beluga smiles at the camera. Belugas are the only whale that can use their lips to form different shapes to communicate. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Peter Kragh)

BASCOMB: Gosh, I sure hope so. This series also documents the formation of a surprising cross species adoption between lost Narwhal, a youth, and a pod of beluga whales. What exactly happened there? And what does that tell us about the culture of whales?

SKERRY: Yeah, thats a really special situation. And these are two polar species that have some similarities. But generally, you're not seeing them in that kind of close proximity. I think that is quite unique. And I think it speaks to the empathy and the accepting nature of these beluga whale families. I mean, clearly, they know that that's not one of their own. But yet they saw this narwhal that was alone, and just made it part of the family. They adopted it as one of their own. And, I mean, how wonderful is that? I think this is one of the messages that I've taken away. You know, I spent three years working on this. As I've processed a lot of these moments that we witness in the series, it occurred to me that I've been reminded of things that I already knew, and that is that community matters, that family matters, that the whales make time for each other. A sperm whale for example, these are matrilineal societies led by the older, wiser females, they spend most of their life in the deep ocean foraging for squid. Life in the ocean is hard, but yet every day or every couple of days, they make time to come together and socialize. You see them rolling around and enjoying each other's company, reaffirming their family bonds. And for me to reflect back on this was to be reminded of how important social creatures are, that humans and whales can't do it alone. We need each other, we need family, we need community, and that that alone can bring us the greatest joy in life.

A narwhal's tusk is a long, hollow tooth that usually only develops in males. Its full function is still a mystery. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Thomas Miller)

BASCOMB: It's a beautiful message. Well how important is it, do you think, to protect not just whale species, but whale cultures? So maybe some sperm whales in one place are doing okay, but if the resident pod and Dominica for example were to die out, what would be lost with them?

SKERRY: Well, that is a wonderful question and nobody has ever quite asked that. And I think it is immensely important. My friend, Dr. Shane Gero, who studies the sperm whales in Dominica, he wrote an op ed for the New York Times a few years ago, called the Loss of Whale Culture, and he specifically cited Dominican whales. He said that they are on a 3% annual decline because of anthropogenic stresses, they get entangled in fishing gear, they get hit by ships. And he argued that historically, biologists would look at that and say, you know, while tragic, it is not the end of the world because even if those whales go away, other sperm whales will come in and fill that niche. But what he says is no, what those whales know about those waters, the seamounts, the canyons, where the good food is, all the things that make them unique, would be lost. I think the loss of whale culture is an important aspect that gets lost in the bigger equation here, but in the way that we want to preserve human culture, we should want to preserve animal culture as well.

Marine biologists Shane Gero and Asha DeVos eavesdrop on sperm whale conversations with a hydrophone. They are listening for dialects that differentiate whale populations. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: It's really like our shared heritage.

SKERRY: It is, absolutely. You know, there's a great quote in my book from Henry Beston, in a book he wrote called the Outermost House about Cape Cod, and I won't get the quote, right, but he basically says that these other species that we share this planet with, they are not our underlings. They are not our brethren, necessarily. They are independent nations that we are traversing this journey on earth with, and therefore we must have equal respect.

A family unit of Sperm Whales socializing underwater in the waters off of the island of Faial in the Azores. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: What do you hope your audience takes away from this series? What's your goal here?

SKERRY: I guess my hope, on a very basic level is that everybody enjoys it that it's entertaining and that they're happy to learn something about whales. But if I could have a bigger wish, it would be that audiences begin to see our planet a little bit differently. If we can look at whales, and as a result the ocean, and as a result our planet through that lens of culture, understanding that these highly cognitive, sentient animals are living in the ocean, that they have rich ancestral traditions, they are doing things much the way that we do, that maybe we will see our planet and our connection to it in a different way. And that maybe we will change our detrimental behaviors to the planet as a result of that. So that would be my grander hope. And that maybe without overtly being about conservation, that it could change the way we do things.

Sperm whales prefer to hunt for squid far beneath the surface. They routinely stay an hour below and can explore as deep as 10,000 feet. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: Brian Skerry is a National Geographic explorer and marine wildlife photographer. Brian, thank you so much for taking this time with me and for this wonderful series.

SKERRY: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a real pleasure.

National Geographic Explorer and wildlife photographer Brian Skerry (Photo: Courtesy of Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: By the way, to hear even more from Brian about the Secrets of the Whales you might consider listening to his free online lecture coming up on May 13, hosted by the New England Aquarium. For details visit the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Stream Secrets of the Whales | Disney+

- Brian Skerry’s official website

- Read More on the Dominica Sperm Whale Project

- Register for a New England Aquarium lecture with National Geographic Photographer Brian Skerry for a virtual conversation about the culture of whales.

[MUSIC: Paul Winter Consort, “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale to the Baby Seal Pups” on Concert For the Earth, by Paul Winter, Living Music]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page – Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth