April 9, 2021

Air Date: April 9, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

View the page for this story

Deep within the remote wilderness of the Alaska Peninsula, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is one of the least-traveled places within the national park system. Designated by President Jimmy Carter as a national monument and preserve in 1978, Aniakchak is always open to visitors with no amenities, no cell service, and no park rangers -- hence its slogan, “No lines, no waiting!” Chris Solomon, who wrote about Aniakchak for Outside magazine, joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his experience among the grizzly bears and volcanism in this wild and remote patch of public land. (11:29)

Why I Wear Jordans in the Great Outdoors

View the page for this story

Some stereotypes in the US among people of European descent about who can be “outdoorsy” can leave people of color out, so environmental educator CJ Goulding actively and creatively works to encourage young people of color to feel that they belong in the outdoors, too. CJ Goulding speaks with Host Steve Curwood about how his Air Jordan “Bred” 11 sneakers help him link young people of color to the great outdoors. (06:54)

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson, Arizona is home to plenty of heat and cacti, of course, but also many species ordinarily found far north of the desert Southwest. With a local biologist as her guide, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on the remarkably diverse biomes of Arizona’s Sky Islands. (10:48)

Spring Awakening

/ Rick BassView the page for this story

Montana-based writer Rick Bass shares the stories of playful grizzly bears coming out of hibernation as winter melts away into spring. (02:13)

A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration

View the page for this story

Every spring and fall, a journey of thousands of miles begins, as migrating birds find their way between breeding and overwintering grounds. It’s an incredible phenomenon that naturalist Kenn Kaufman brings to life in his book, A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Kaufman is the author of the Kaufman Field Guide series and is also a contributing field editor with the Audubon Society. He joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his latest book and what our species can do to avoid harming birds on their remarkable journeys. (15:49)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210409 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Rick Bass, C.J. Goulding, Kenn Kaufman, Chris Solomon

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

Getting more people of color out in nature, starting with familiar footwear.

GOULDING: For me the idea of connecting people to nature sometimes it's like a river that's or a creek that's running by and you can't jump it immediately. You're not comfortable enough to make that large leap. And so, the Jordans helped me to be that steppingstone in the middle.

CURWOOD: Also, visiting Aniakchak National Monument, where there are no crowds!

SOLOMON: In 10 days, we saw two other people and they were fishermen who had simply pulled up on shore to just poke around for a few minutes. Otherwise, we saw, more bears than people; we saw beauty that I still tell people about.

CURWOOD: That’s this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Aniakchak’s renowned caldera is a beautiful reminder of Alaska’s location within the Ring of Fire. (Photo: Courtesy Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

For many in the US, with the promise of more vaccinations against covid-19 and summer just around the corner, the urge to travel is coming on. But here and abroad there are many more people yet to immunize, and waves of the pandemic can make travel risky. One of the safest places to go is outside, where bright sun and heat can quickly kill the airborne virus, and few places are better than our wonderful public lands. Today and next time we have some stories that explore some vacation possibilities in US public lands.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, “This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co.]

Today we look to Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve in southwest Alaska.

Aniakchak it is one of the least visited of our public lands and touts the catchphrase, “No lines, no waiting”. And it’s for the most adventurous among us as there are no roads to Aniakchak. You must arrive by plane or by foot. But Outside Magazine contributing editor, Chris Solomon, says that’s part of the charm. Chris, welcome to Living on Earth!

SOLOMON: Oh, thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: What made you decide to go to one of the least visited places in the national park system?

SOLOMON: I really like to go as far off the map as possible. I mean, I've joked that my cell phone is a, is a bit like a reverse Geiger counter. As the cell phone bars of coverage drop, the possibility of adventure and a good time seems to increase. Everybody talks about the most popular national parks, and those places are great. But I wondered, what's the least popular place? And I wondered, is there something interesting about that place? Or maybe, why is it so unpopular? There was a list on the National Park Service website of the places that got the fewest visitors. And year after year, Aniakchak anchors the bottom of the list or is very close to the bottom.

CURWOOD: So, remind me, where in Alaska is Aniakchak actually located?

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve resides on Alaska’s peninsula, which leads into the Aleutian Islands. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: It's 350 to 450 miles, I forget exactly, southwest of Anchorage on this stub of a peninsula called the Alaska Peninsula that's warted with these quiescent volcanoes. It's where Katmai National Park is that people have probably heard of. Lake Clark National Park is in the area, these better known national parks. And then after the peninsula runs out, the Aleutian chain begins with people are probably more familiar with at least from a map. But, Aniakchak is on that peninsula as well. But, it's so little known that even as we sat in the airport, there was a big mural on the wall and these other national parks were on there and Aniakchak wasn't even on the mural in the airport as we headed there.

CURWOOD: What kind of company did you have with you, both two-legged and four-legged?

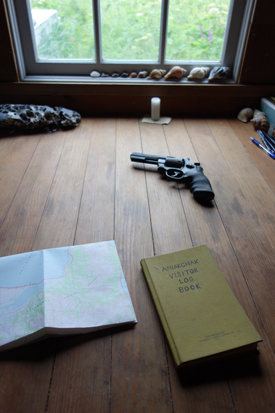

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so it was just three of us. There was a great photographer named Gabe Rogel, who's now a good friend. And our guide was Dan Oberlats who is the founder and chief guide of Alaska Alpine Adventures. So, it was just us three, along with a 44 Magnum called Pepe that was Dan's, to try and keep the bears at bay, because the Alaska Peninsula is, is known for some of the heaviest concentrations of the largest brown bears on Earth. They're relatives of the Kodiak brown bears, which are often said to be the largest bears, but the Alaska Peninsula bears are basically the same bears. One census found 400 brown bears per 600 miles, which is just astounding. I mean, there's something like 700 bears in 60,000 square miles of the Yellowstone ecosystem.

Chris’s guide carried a gun named Pepe to defend against grizzly bears. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Oh, my! So there you are, you head to Alaska, to Aniakchak, but I guess you just don't rent a car in Anchorage or something and start driving.

SOLOMON: No, you don't. So, you have to fly to for instance, King Salmon, which is one of the bases of the Bristol Bay Salmon Fleet, and then maybe try to get to Port Heiden, which is a little dot of a town. And then, from there, you could either potentially fly a float plane into the monument, or in our case, the weather's so bad and unpredictable that we just decided to hoof it from Port Heiden. And we hiked about 22 miles up into the centerpiece of Aniakchak, which is this spectacular caldera.

CURWOOD: What exactly is the caldera?

SOLOMON: Yeah, so a caldera is essentially a volcano that has blown up, and then collapsed on itself and leaves a big bathtub. Essentially an empty ring, maybe the one readers would know best is Crater Lake in Oregon. And so Aniakchak has this great history and, it was so fun to discover this stuff, Steve. About 7,000 years ago, as the Egyptians were kind of doing their thing and really dominating the Mediterranean area, this several thousand foot volcano, Aniakchak would have been, blew its top with the force of something like 10,000 atomic bombs. And then it, having done that, it collapsed upon itself. And over the course of a couple thousand years, it filled with several thousand feet of water. So it was this bathtub, and then one of the sides burst out with this tremendous flood. So then it became this empty ring with a hole in one side. And one of the great discoveries of doing this story is, you know, the native peoples, of course, knew about this place. But then in the early 20th century, this incredibly charismatic guy named Father Joseph Hubbard, who was called the “glacier priest”, came and quote-unquote, rediscovered it. And the glacier priest was this swashbuckling Jesuit from Santa Clara University, he would go on these expeditions around, around Alaska, often with a bunch of football players from Santa Clara University with their leather helmets on and they went to Aniakchak and they explored it. And they had found this place that hadn't blown up again in a couple thousand years. And inside were all these orchids growing in the warm soil, and they had bunnies that hadn't seen man. And so they would just walk right up to the football players who, who then ate them for dinner. And he described this sort of paradise found. And he wrote about this for, you know, places like National Geographic, and then he went away, and that year, it blew up again, and he came back and he described this kind of Dantean Inferno, and the place almost killed them with all the sulphurous gases. And so he wrote about it again, and became even more famous. So the glacier priest was one of the great finds of this story, and I was able to kind of follow some of his tales and writings as we explored the place.

At the bottom of Aniakchak’s caldera is Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: So take me back to a memorable moment or two for you in Aniakchak National Monument.

SOLOMON: We drop into the caldera after just being completely in the mist, you know, not knowing what we're going to find. And we drop into the caldera the second day, and we see this amazing place, and we camp by this beautiful little lake that's still the remnant of the bathtub that had been filled. And it's this lake called Surprise Lake where salmon still swim up into it and spawn, and they apparently taste like minerals from all the volcanic stuff that's still in the lake. And the next day we crawl out and we get on to the rim and you can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this, you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of you know of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it and it's just -- I still have the, the picture as my screensaver on my computer because I never tire of it.

CURWOOD: Is there another memory you have from there that you would like to share that’s sort of incredible?

Orange lava flows and hot springs speckle the bottom of the caldera, bleeding into Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: You know, one of the -- [LAUGHS] this might not be the kind of experience everyone wants, but we rounded a curve in a bay as we were exiting the monument. And around the corner, maybe a couple hundred yards away, was a, was a brown bear who was snuffling around, maybe he was on a kill, we couldn't tell. And he headed up on to the bluff where there was a lot of alders and underbrush and we couldn't see him anymore. That's not great because you want to keep an eye on the bear. So we decided to cut the corner across the bay and just walk through the tide flat and keep our distance. So we took off our shoes and started walking across the tide flat and the tide flat turned out to be almost thigh deep with tidal mud. So now we're reduced to walking at about one step every four or five seconds, as the mud is just sucking at our bodies. Meanwhile, we can hear the bear 150 yards away chuffing, you know, making unhappy noises in the underbrush. And then we get to the other side of the, of the bay. And the guide encourages us to walk as fast as possible. And I notice that he has drawn Pepe, the 44 Magnum, which encourages you to walk even faster. And we get to the other side of the brush. And we have no idea where the bear is. And there's a small path through the woods that we have to take. There's no alternative. And it turns out that it's what's called a bear trail. And these bear trails are these habitual paths that bears use for years, sometimes a century, sometimes longer. They're just, they're bear highways. And it was so well used by bears, by these thousand-pound bears, that the bear trail was knee deep with use. It was so worn. So we're walking through this incredibly dense thicket. We can't see 10 feet in front of us, with gun drawn, screaming and yelling 'hey bear!' 'Hey, bear!' with no idea where the bear is. And then we pop out on the other side safe. And we inflate our little rafts, and we float across a bay. And there's whales diving and puffins flying, and it was just a great end after a lot of adrenaline. So, [LAUGHS] It's the kind of thing that, you know, makes the colors a little brighter in life.

CURWOOD: How worth it was it to go?

Brown bears are highly abundant within Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: For someone like me who values wilderness, and solitude, and adventure, and who is willing to endure a little bit of discomfort and sogginess and freeze dried food [LAUGHS] for that payoff. It was a memory of a lifetime. And if you too are of that bent, I would encourage it highly. In 10 days, we saw two other people and they were fishermen who had simply pulled up on shore to just poke around for a few minutes. Otherwise we saw, we saw more bears than people; we saw beauty that I still tell people about. I made some friends for the rest of my life. I do find, and as I've written elsewhere, that the few people you go out with on these kind of experiences, these kind of wilderness experiences, have a way of really sharpening the relationships among the people that one spends time with. In short, it was one of better experiences of my life.

CURWOOD: Chris Solomon is a contributing writer for The New York Times and Outside Magazine. Chris, thanks so much for joining us today.

SOLOMON: Oh, it's my pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: And, I'm glad the bears didn't get ya.

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] So am I!

Chris Solomon is the Society of American Travel Writers 2018 Travel Writer of the Year. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

Related links:

- Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

- Outside | “Baked Alaska: Surviving Aniakchak National Monument”

- Chris Solomon’s Website

[MUSIC: Ray Charles, "America The Beautiful" on Ray Charles Forever, Concord Music Group]

CURWOOD: Stay tuned as we travel to a National Forest in the rugged mountains of Arizona. You’re listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chris Belleau, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” on Swamp Fever, by Charles Mingus (Chris Belleau/Proud Dog Records)]

Why I Wear Jordans in the Great Outdoors

CJ Goulding has only ever owned one pair of Air Jordans – a status symbol to some African-Americans -- but he’s not too concerned with keeping them pristine. (Photo: Cherish, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood.

Plenty of backpackers wear special hiking boots when they are out on the trail, but not C.J. Goulding. CJ is a Program Manager for the Children and Nature Network and when he leads young folks out for a hike CJ himself wears Nike sneakers called Air Jordans. Here’s an excerpt from his blog on why.

GOULDING: I am an African American natural leader. That phrase is not an oxymoron but it's also not something that you normally see in the environmental world. In the few years that I've been involved in environmental education and connecting people with outdoor spaces, there have been numerous occasions where I'm the only person of color in the program, or the only African American leader. Growing up, there was no one from my neighborhood traveling, hiking, canoeing, or spending time outdoors unless it was a part of a regimented program.

But do not misunderstand the meaning behind that statement. Do not miss my point. I write neither to complain that the outdoor world is an elitist one, nor to lament the disconnect between the world I grew up in and the natural world where I now lay roots. I write to celebrate the amazing opportunity available for me and others like myself to be a bridge between the two worlds.

On my feet as I write our Jordan Bred 11s the only pair of Michael Jordan sneakers I've ever owned in my life. His sneakers are a status symbol in the neighborhood I grew up in, a memento of importance and significance. Unfortunately for some people, they hold higher value than food, books rent, and in some extreme cases, even the life and well being of another individual.

So it makes sense that while facilitating an outdoor youth summit at Harpers Ferry National Park in Virginia, an African American teenage boy stopped me to ask why I was wearing these Bred 11s outdoors. I laughed. I asked him if he had seen anyone who would wear Jordans exploring the outdoors like we were. He said no. Right there, the disconnect between the two circles was evident and as we looked around, we could see that even there at that event, we were in the minority.

I've heard the rallying cry echo, through the trees affirming that the outdoors are for people of all creeds, countries and colors.

My Jordans are now falling apart, worn from adventures in places like the Grand Tetons and the Grand Canyon. Hiking through the topography of Los Angeles and Arctic Village. This goes directly against how people quote unquote should wear them and what people quote unquote should wear outdoors. But I wear them wherever I go to remind me of the fact that though there are two worlds, I am a bridge. And I'm constantly reassured of its validity whenever I see another young leader follow the footprints of my Bred 11s into the woods.

CJ Goulding leads participants from Los Angeles and Alaska in the Fresh Tracks: Leadership Program. Fresh Tracks is a cultural exchange program that builds participant skill/knowledge in cultural competence, civic engagement, and hometown stewardship. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: So CJ, what was the outdoors experience that hooked you?

GOULDING: Growing up as a kid I was a wanderer and so I'd just explore the neighborhood, the trees, any forested areas, my grandmother's backyard, spending a lot of time working in her garden, and planting things and flowers and vegetables and things like that. So that's a key component of my environmental ethos.

CURWOOD: CJ, what do you think it is that keeps Black people away from nature here in the United States?

GOULDING: I think white supremacy has existed to amplify the disconnect that we have had with nature. A lot of times, history of Black people and African Americans is told starting at slavery, and that's not true. Before that, way before that we had a connection to the land, we had a connection to each other and communities. And so oftentimes, that story gets lost. And it's on purpose because a grounding and a connection in nature, amplifies and completes us and strengthens our culture. So that disconnect shows up through the way that communities of color and black people live inside inner cities with not easy access to nature, that shows up in the way that our education doesn't include that kind of knowledge. That shows up in the way that white folks have taken over some of these industries connected to the outdoors and made them an experience that requires a lot of time and a lot of money. So that connection is always with us. But I think white supremacy showed up in a way that wants to separate us from these life giving qualities.

CJ Goulding has been involved in REI’s #OptOutside campaign, which is aimed at connecting people to nature and reducing waste across the outdoor industry. (Photo: Tony Teske, REI)

CURWOOD: Tell me how do you think the the Jordans Bred 11 helped to connect with folks.

GOULDING: I call it my stepping stone theory. And for me the idea of connecting people to nature or connecting people to anything unfamiliar sometimes it's like a river that's or a creek that's running by and you can't jump it immediately. You're not comfortable enough to make that large leap. And so the Jordans helped me to be that stepping stone in the middle where I'm able to build a connection with someone and help them feel comfortable stepping into the middle because they understand that I'm there. They connect to me because I'm showing up as myself because they understand that I know who they are and where they come from. And then they feel more comfortable stepping into that unknown whether it's nature or anything else in terms of development and exposure that they're looking for.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent did you get pushback or question or even ridicule from white people who saw your show up in what they see is anachronistically his tennis shoes?

GOULDING: I think sometimes it shows up as 'hey, you're not wearing the right shoes' because they think they know the correct shoes to wear outside or outdoors and understanding that the outdoors can get to gear centric and you really don't need right shoes. You don't need $120, $200 boots to go outside. All you need are the sneakers that are on your feet.

CJ Goulding is lead organizer at the Natural Leaders Network based in Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: Those Jordans aren't cheap though.

GOULDING: Well mine where I got those for $4.95 at a thrift store in Alabama, so I would definitely consider that inexpensive.

CURWOOD: So after they said those aren't the right shoes, what did you say to them?

GOULDING: I don't care. [LAUGH] I mean, I realized that I had something to teach them as much as they had to teach me. Understanding that there are some cases where I need special gear and equipment and then understanding that there are some cases where it's just marketing. And I knew that my primary purpose was one to stay safe and I was doing that but ultimately to connect with the young adults I was working with.

CURWOOD: CJ Golding is a program manager for the children and Nature Network. CJ, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GOULDING: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read more from CJ Goulding

- CJ Goulding is a Lead Organizer for the Natural Leaders Initiative from the Children & Nature Network

- CJ Goulding's essay is featured in the book, “Coming of Age at the End of Nature”

[MUSIC: Steely Dan “Pretzel Logic” on Pretzel Logic, MCA Recordings 1974]

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

Coronado National Forest has an area of nearly 2 million acres spread throughout southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, including the Sky Islands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Arizona is home to millions of acres of public lands suitable for hiking. In fact, more than 50 percent of Arizona is public land, a tapestry of state and federal reserves, including the iconic Grand Canyon. That makes it a popular destination for summer travels. But if you are worried about desert heat and crowds, consider the way less traveled Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb found the woods there are literally full of cool surprises as she hiked and drove up Mount Lemmon, roughly 80 miles north of the US border with Mexico.

[SFX CAR PASSES]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on the side of the road at the base of Mount Lemmon. It’s sunny and a pleasant 75 degrees. Sharp grasses and spiny succulents with bright yellow and pink flowers blanket the parched desert ground. I’m here with wildlife biologist Sergio Avila.

AVILA: We can see Sonoran desert plants and animals. We can hear right now some cardinals, we can hear some cornfield thrashers, we can hear some mockingbirds.

BASCOMB: Sergio is outdoors coordinator for Sierra Club in the Southwest Region. Originally from Mexico, Sergio has thick black hair pulled back in a low ponytail.

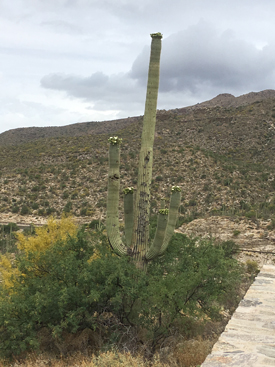

AVILA: We are looking at the saguaros, which is the iconic, kind of descriptive plant of the Sonoran Desert.

BASCOMB: These saguaro cactuses stand sentry some 60 feet tall with large white flowers on each of their massive arms reaching upwards. I think the inventors of those cactus-shaped margarita glasses must have had the saguaro in mind.

The Saguaro cactus is an icon of the Sonoran Desert. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: So, for a plant like this, to have some arms, at least 250 to 300 years have passed for them to have their arms. So a lot of these saguaros that we see here are easily three, 400 years old, so they're ancient saguaros.

BASCOMB: Some of these cactuses may have been here when the Spaniards were establishing settlements. But Sergio says the native people of the area, the Tohono O’odham, have always had a close cultural connection with the saguaro.

AVILA: The new year, or the year for the Tohono O’odham starts on July 1st, and that is connected to when the fruit of the saguaro drops from the plant and around when the rainy season starts.

BASCOMB: And he tells me the fruits of the saguaro are an important food for everything from mice and skunks to foxes and coyotes. Their flowers provide pollen for a variety of bats and birds. Their shallow roots are crucial for holding soil intact during the monsoon rains. And the body of the cactus itself provides housing for a number of residents.

AVILA: Saguaros are like apartment buildings with cavities, and so little owls, kestrels, woodpeckers, many other birds depend on saguaros to live inside of these cavities.

Sergio Avila is a wildlife biologist, as well as an outdoor activities coordinator with Sierra Club. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Unlike the Sahara, the monsoon rains pour on the desert here each summer, and scientists say that makes it this the wettest desert in the world. So even in the dry season, the Sonoran landscape is teeming with life. But as captivating as it is, there is so much more to see. So, Sergio and I pile into our car and head up the mountain.

[SFX CAR DOOR SLAMS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We drive around a bend in the road and suddenly the saguaro are gone. Within 1000 or so feet of elevation gain, it’s too cold for them.

[DRIVING SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

We pass a scenic overlook, Tucson lies below us, and from here it’s clear to see why these are called sky islands.

AVILA: The sky islands, here in Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent parts in Mexico, are mountain ranges surrounded by grassland sort of deserts that make them look like islands.

BASCOMB: Back 15 to 20 thousand years ago, the climate of the southwest was much cooler and wetter. With the end of the last ice age, temperatures rose and desert came to dominate the landscape. But at higher elevations, temperate plants and animals were able to survive. Today those remnant biomes are marooned as mountain islands, surrounded by the sea of the desert.

Mount Lemmon. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: In this region of the sky islands, is the only place, or is the place where jaguars and black bears meet. It’s the place where you have northern birds like sandhill cranes, and birds from the tropics, like military macaws.

BASCOMB: The Sky Islands sit at the confluence of 4 different ecosystems, the Rocky Mountains to the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, and Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts. With so much diversity in one area, Sergio says, the sky islands are a biodiversity hotspot.

AVILA: So this biological region brings together a species from the north and the south that they don't meet in anywhere else.

[SFX CAR DOOR SHUTS]

BASCOMB: We get out of the car and walk along a small trail. The path we are on is actually part of the Arizona trail that goes from Mexico to Utah. We are driving up Mount Lemmon today but you can also hike the mountain in about 5 hours.

AVILA: I think right here we're at about 4500 feet of elevation. We've been going up on the mountain, and you can see a little bit of the change. Now we start seeing some oak trees. And I have to say, I'm pretty cold.

BASCOMB: I'm chilly.

AVILA: Yeah, yeah, let's go see what we see over here in the trees.

BASCOMB: We’re walking in an oak woodland, but dotted in the understory of a forest you might see in Pennsylvania are huge cactuses, waist high covered in orange and yellow flowers.

AVILA: This is a prickly pear. Eventually those flowers will turn into prickly pear fruit, which is a super juicy fruit that is a tremendous food source and water source for a lot of animals.

BASCOMB: It makes a good cocktail too.

AVILA: Oh, well I'm glad you mentioned that because part of the trip includes prickly pear fruit margaritas and that is a sky island staple. (laughs)

The Sky Islands are in the midst of four different ecosystems – the Rocky Mountains in the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, the Sonoran Desert to the West, and the Chihuahuan Desert to the East. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh perfect.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

AVILA: One thing I wanted to share, for example, this region has four different species of skunks.

BASCOMB: Really?

AVILA: Yeah, so it’s not, you know, just skunks, but we have striped skunks. We have spotted skunks, we have hog nose skunks, and hooded skunks.

BASCOMB: And are they all just as stinky?

AVILA: No! Those who are specialists in skunks actually say that different skunks smell different. Those who have experience with skunks can even tell one skunk species from the other from their smell. Which, you know, I think it's a level of skill that I don't know if I'm ever going to get to but…

BASCOMB: Do you really want to practice? [LAUGHS]

AVILA: Ah, exactly right. Like, what does what does it take to learn that? But it also speaks about … skunks, eat insects, skunks dig around for rodents, skunks might eat some reptiles. So the fact that we have four different species of skunks, in my mind says that we have a tremendous diversity of insects and rodents, and everything that is food for skunks, you know what I mean? We also have two different species of deer, white tail and mule deer, or black-tailed deer, that are adapted to a different elevation. We have four different species of cats in this region. The better-known bobcat, which is the short one with a short tail, and the mountain lion, or the cougar. And then the tree tropical ones, which are the ocelot, and the jaguar, the two spotted cats that come from the tropics. Having four species of cats, it's also an indication that we have a lot of different animals that can be food. And so the sky island region is a really good example of a whole ecosystem working together.

BASCOMB: So, these sky islands are a chain of mountains that start near San Javier, Mexico, 300 miles south of the border, and run into Aravaipa, Arizona, some 200 miles north of the international boundary. These mountains are a crucial corridor for migrating animals, like jaguar, that can migrate several hundred miles in search of territory and a mate. So, I ask Sergio how a high-security border wall could affect migrating wildlife.

Sky islands are mountains whose ecosystems are drastically different compared to their surrounding lowland environment. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: You might be separating populations of carnivores, you might be separating populations of herbivores that are making use of some areas. And so this rich diversity in our region is very important. And it's one of the things that is under threat, short term by the border wall and other infrastructure there, and long term by climate change.

[CAR SOUNDS, DRIVING]

BASCOMB: Back in the car, we head up the mountain again. At about 7,000 feet of elevation, the oaks and cactus give way to pine trees. It looks exactly like a typical forest in New England. Around the corner we need to stop the car.

SERGIO: So we're looking at two white-tailed deer on the side of the road. They look like really young fawns. I would say these are young, from this last summer. I wonder where mom is.

BASCOMB: We peer into the thick vegetation, but don’t see mom, so once the deer are safely across we continue on to the top of the mountain to the Mount Lemmon Ski Valley. That’s right, alpine skiing in Arizona.

SERGIO: We are at 9000 feet of elevation in the ski area, the top of Mount Lemmon. We are surrounded by a meadow of aspen. If you've ever been in Colorado, you will recognize these trees very quickly. And we are in front of this ski lift and it is snowing. And here we are prepared for a field trip in the summer in Arizona and we are super cold.

Mount Lemmon reaches heights of over 9,000 feet and its summit area receives around 200 inches of snow every year. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: I'm wearing shorts and a sweatshirt and I'm uncomfortable. The thermometer in the car says it's 35 degrees up here. There’s snow sticking in your hair.

AVILA: Yeah. I also wanted to say we are seeing different birds, we saw a robin. Seeing different colored birds, but it is very gray and clouds are very dense. And so even the sound is kind of like hard… It’s not very noisy right here and so we only hear the wind blowing in the aspen trees. It is pretty, but it is cold.

BASCOMB: When we were driving up here we saw signs that say snow plow ahead and beware of ice, and that sort of thing.

SERGIO: And we were laughing at those signs on the road. Yeah, what did we know?

BASCOMB: We're not laughing anymore!

SERGIO: We’re not laughing anymore, no!

The trail map for Coronado National Forest, outlining the Sky Island Scenic Byway. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In terms of the climate and habitats, we’ve gone from Mexico to Canada in less than an hour. We warm up with some hot chocolate at the top of the mountain and then head back down the way we came. My ears pop with the sudden elevation change and I’m struck by the remarkable diversity one small mountain has to offer. And in the monsoon season, it’s different still, when a flush of life emerges to greet the rain and complete an entire life cycle in a matter of weeks. Far from the barren desert one might imagine, the Sky Islands of Arizona are full of surprises and well worth a visit nearly any time of year.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in the Sky Islands of Arizona.

Related links:

- Coronado National Forest

- Listen to another Living on Earth public lands segment about North Cascades National Park

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, “Walkin’ In Music” on Next Generation, by Julian Lage, Concord Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, longer days mean bears are coming out of their long hibernations. Keep listening to Living on Earth

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Time For Three (featuring Branfor d Marsalis), “Queen Of Voodoo” on Time For Three, by R.Meyer & N.Kendall/arr.Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics]

Spring Awakening

A black bear sow and her cub walk through Tower Fall in Yellowstone National Park on a May afternoon. (Photo: Neal Herbert, National Park Service, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth I’m Steve Curwood

Writer Rick Bass lives in the Yaak Valley of Northwest Montana. He says there is a point in the spring when sleep gives way to rambunctious wakefulness, where winter has truly left and won’t be coming back for many months.

BASS: The snow is melting. The grizzly bears that have been sleeping beneath the snow, suspended like seeds, will prowl the warm fields just beneath the snow, grazing on the delicious emerging lilies. Sometimes the yellow pollen gets caught on the fur and snouts of the great golden bears as they grub and push through the lily fields, pollinating other lilies in this manner. In this crude fashion, they are farmers of a kind, nurturing and expanding one of the crops that first meets them each year. The lilies follow the snow, and the snow pulls back to reveal the bears, and the bears follow the lilies. The script of life begins moving with enthusiasm once again, a script and a story more exuberant than any that has been seen so far this year.

Rick Bass is a Montana-based writer and environmental activist. (Photo: Courtesy of Rick Bass)

And on winter’s remnant glistening ice shields, which grow smaller every day, the grizzly mothers with their cubs slide down the slopes on their backs. They ride the ice to the bottom, cartwheeling into fields of lilies, resting at the bottom of the vanishing glacier, and then climb right back up to the top. They slide and play for hours at a time, safely distanced from the new and changing world that lies along the river bottoms and in the lower elevations where people live. There is nothing but joy and new wakefulness running through their blood.

And though there are none of us who can tell by a certain murmuring of our own blood, when it is exactly that the bears climb back up out of the earth, I like to think that the other creatures of the forest can sense it. As easily as we might hear and feel the warming south winds moving through the tops of the pines. I like to think, too, that that joy is as transferable as felt and connected among all the inhabitants of the forest, as are the south thawing winds upon the land and upon and among all of us.

CURWOOD: Rick Bass lives and writes in the Yaak valley, in Montana. This snapshot of bears and lilies at the end of winter comes from his book, The Wild Marsh.

Related link:

Rick Bass's website

[MUSIC: Noah and The Whale “Instrument al II” from The First Days of Spring, 2009 Mercury Records]

A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration

Many songbirds are known to make their migration during the nighttime hours. (Photo: Unsplash, Barth Bailey, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Kenn Kaufman is a renowned writer, artist and naturalist who has produced a variety of books focusing on the natural world, including the eight-part Kaufman Field Guide series. Since the age of six, Kenn has been a self-proclaimed bird nerd. He joins us today from northwest Ohio to talk about his 2019 book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Thanks for being with us, Kenn!

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's great to talk with you.

CURWOOD: Your new book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." But you've written a bunch of them, how many guide books?

KAUFMAN: I've written about seven actual identification guides to nature. And, then a couple of books actually intended for reading.

CURWOOD: So we shouldn't read the guidebooks, huh?

KAUFMAN: Oh, well, a lot of people just look at the pictures!

CURWOOD: But, I bet little Kenn would have actually read it from cover to cover.

Kenn Kaufman’s new book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration is available now. (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) I would have, yes. The guide books that I did have I did read cover to cover. I had memorized books by Roger Tory Peterson by the time I was 10 years old.

CURWOOD: What prompts, a kid really, to have practically memorized a field guide to the birds by Roger Tory Peterson.

KAUFMAN: Well, I was just so fascinated with birds as a little kid. I mean, I, I sort of discovered birds when I was about six. And, when you look at things like robins or grackles out on the lawn, and you get close to them, which you know, as a kid, you could just crawl across the lawn. Nobody thinks anything of it. Those birds are just so intense. They are so intensely alive, that I was just captivated by looking at them. And, so, I've just been utterly fascinated with birds and then with other aspects of nature, ever since I was six or seven years old.

CURWOOD: So, last time we spoke you were in Arizona, why are you in Ohio?

KAUFMAN: Well, I mean, Arizona is great for natural history in general. And there are a lot of birds there. But bird migration is not so obvious there as it is in eastern North America. There's just more birds that pass through the eastern half of the United States. And this area, Northwestern Ohio, the edge of Lake Erie, is really a fabulous concentration point for migratory birds.

CURWOOD: Well, how do you see them? Because as you write, the songbirds migrate principally at night.

Warblers are the most popular of the migratory songbirds that mark the peak of spring migration. The Blackburnian Warbler spends the winter in the Andes in South America, migrates north in spring through Central America, across the Gulf of Mexico, through the eastern U.S., heading for breeding grounds that are mostly in the spruce forests of Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: That's right! So, it's sort of this massive phenomenon that's largely invisible. And, that's that's part of what makes it interesting. But here, birds are coming north on a broad front across eastern North America, they come North across Ohio, they get close to the edge of Lake Erie, and if it's approaching dawn, they can see that there's water ahead. And these birds will just come down and then land and so the numbers pile up on the edge of Lake Erie, the little wood lights there. On a good morning, after a good night, those woods are just full of these small songbirds. They concentrate there, and often they'll stay for several days feeding and fattening up for the next flight.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a term that's often thrown around where birds go during migration called flyways. But you write that flyways are a dated concept, why?

KAUFMAN: It's an interesting concept. The idea of bird flyways was developed first by people who were studying duck migration. And it was easy to study duck migration, because you can catch a bunch of them at once at some water area and put bands on their legs and then later ask the hunting community to send in the duck bands from the ducks they've shot. You very quickly can get a sense of where a lot of these birds have gone. And ducks do sort of follow specific flyways from one water area to another. But the great majority of birds don't follow anything like that. If you could look down on North America from outer space on a night at the peak of migration to see where the birds were going, you wouldn't see rivers of birds flowing toward the north. It would look more like a blanket of birds being pulled northward.

CURWOOD: And, yet, you write that people often come at the spring migration time to where you live there in Northwest Ohio. So if it's not a flyway, why do people come from all over the world to watch the migratory birds in your neighborhood?

KAUFMAN: They come there, because of the sheer concentrations of birds. The birds are moving north on a broad front. So, there would be just as many individuals passing over an area, say 150 miles farther west. But in this area, they're pausing because they're coming up to the edge of Lake Erie. And, we also have a lot of really good habitat here. So, birders can spend all day, or spend all week, going from one wood lot to another, or going to the marshes, going to the fields. And every place they go, they'll see concentrations of these migratory birds that are stopping over.

CURWOOD: By the way, what about the fall migration?

In the summer the Eastern Kingbird live in the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and southern Canada, feeding on insects in open country. In winter, they gather in flocks in the Amazon rainforest, feeding on small fruits in the treetops. Talk about a double life. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, fall migration is exciting. Actually, for the, the really serious birders they're often more excited about fall migration. There are more birds then. The total population is higher because the birds have been hatching young all summer. So you have all these young birds migrating south for the first time. So, the numbers are higher, and the young birds are more likely to wander out of range. So you'll get more rare birds, more things in places where they shouldn't be, during the fall. So, it's a very exciting time for birding. But to me, the thing about spring is that it's just a sense of resurrection, almost. A sense of rebirth. Especially if you're in northern Ohio, and things have been frozen solid all winter, and things start to thaw out. And all these birds come back. It's just such a, such a wonderful feeling that I can't help just wanting to go out and celebrate.

CURWOOD: Let's just say that one of the spring mornings, I'm with you there near the coast of Lake Erie. Springtime migration is happening. What does it sound like? What does it look like?

KAUFMAN: It's just a fabulous experience, if you can be out there at dawn or just before first light, along the edge of Lake Erie because you hear the night sounds, of course, there are the frogs and insects and there are a few night birds, like screech owls that are calling. But, then you hear the sounds of these birds. A lot of these nocturnal migrants are calling in flight, doing these little chip notes, little buzzes and things. And you hear more and more of that as the birds come lower. And some of them are coming in from the south and landing in the trees. But then as it starts to get light, you look out and there's small birds sort of flying along, paralleling the edge of the lake. There are others that are actually coming in from the north. Because, when these birds are migrating, if they're out over the open water when it gets light, they'll actually climb up somewhat higher and look around. We know this now from radar studies, right at dawn, we have birds arriving from all direction. Some are just pitching into the trees, some are flying along, paralleling the shore of the lake. And it's just an amazing amount of movement. It's just, it's like the whole world is alive with this movement of birds.

CURWOOD: How do they know where to go?

KAUFMAN: You know, that's a question that people have been working on for a long time. It's an amazing instinct that these migratory birds have. There are some kinds of birds that actually learn their migratory routes. Some things like cranes, for example, or swans or geese, the young birds just follow along with their parents and learn the route. So it's a tradition thing, not so much an instinct. But on the other hand, most of the small migratory birds, they're just going on instinct. And you can just leave a warbler, just drop it off in the north woods, and it will find its way from northern Alberta, perhaps, down to Brazil, without any guidance, without anyone showing it where to go. It's amazing that they've got this instinct. And then a lot of these small birds that migrate at night, they can navigate by the stars, they can detect the Earth's magnetic field. A lot of them can hear very low-pitched sounds, so they can hear, like, the sound of waves crashing on the beach from many miles away. We're still figuring out and still learning some of the things they use, but the navigational abilities of these birds are extraordinary.

CURWOOD: And yet we use the phrase birdbrain.

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) Yeah, I think birdbrain should be considered a compliment.

The Blackpoll Warbler is an extreme migrant among the warbler family, nesting across Canada and Alaska, wintering east of the Andes in South America. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

CURWOOD: So, in your book, you mentioned that birding is now seeming to become a more welcoming and diverse hobby. Talk to me a bit about that, and why you think that may be.

KAUFMAN: When I was a kid, birding was mostly a hobby for really well to do, you know, older white people. And even just as being a kid, I was sort of an oddity. And I once I wrote some books about birds in nature, and I started traveling around the country, speaking to bird clubs and things, it was really disturbing to me to see that I could go to some place where I knew that there was a very diverse local population, but I'd look out at the audience and just see a sea of white faces. And these people were all, you know, they were all perfectly nice, but I was just thinking about people who are not there. But now there are a lot of people who are starting to break down the stereotypes and the old barriers. And so when I go out in my local area on the boardwalk Magee Marsh to look at the migrating warblers in spring, I see a really diverse crowd. They're getting more and more families coming in. There are more people of color, there are people from other countries and other continents coming there. We're seeing lots of young people and every birdwatcher knows that diversity is good. You know, you want to go out and see lots of kinds of birds. You want to go out and see lots of kinds of people looking at birds. So to me, this is the best thing about what's happened in recent years.

CURWOOD: Kenn, what are some of the top locations here in North America that you suggest for migration birdwatching?

KAUFMAN: Some of the areas that are really outstanding in spring include the upper Texas coast, going over into Southwestern Louisiana. Just amazing numbers of breeds that stop off there in certain conditions in spring. There are places out on the Great Plains that are wonderful for shorebirds, some of the wetland areas in Kansas, for example, Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivira refuge in Kansas sometimes have amazing numbers of sandpipers that have come from South America and are headed to the Arctic. There are places in Florida, the Dry Tortugas off the end of the Florida Keys, wonderful area for migratory birds. And then when you turn it around and start looking in fall, there's a different set of places so that, for example, Cape May, New Jersey is one of the best places in the world to see migratory birds in fall. The area of Duluth, Minnesota right at the western end of Lake Superior is a fabulous place for fall migration.

CURWOOD: By the way, what have you observed in terms of climate change affecting bird migration?

KAUFMAN: I don't know any bird people who deny the reality of climate change, the fact that it's happening, and we're starting to see how it has an impact on birds. There are quite a few areas now where there are long term studies where we know that the birds are arriving earlier in spring. Arriving on average, like five to 10 days earlier. And in some cases, that puts them in difficult situations, because in some places, the birds are coming back a few days earlier, but the trees are leafing out much earlier than they used to. So the peak of insect populations now may be happening earlier in the season. And the birds are not in sync with it the way they would have been at one time. And I think we're still in early stages of it, and still in early stages of the studies. But I think we're going to see more and more impacts of climate change on these migratory birds.

CURWOOD: May be climate change, it may be chemicals, it's unclear, but there does seem to be a mass insect collapse going on. How do you think this is affecting the migrations for that matter, the whole business of being a bird?

KAUFMAN: Well, certainly a decline in inside populations is bad for birds, the majority of bird species in the world do feed on insects. So they're like the basic main item on the menu. One thing that's been determined recently is that, for birds that are wintering in the Caribbean, for example, there are long term studies in Jamaica, they found that if it's a really dry, warm winter, and insect populations are low, some of the migratory birds leave later in spring. You would think they would leave earlier just wanting to get out of dodge, because there's not much food. But apparently it takes them longer to build up fat reserves that they need. And that puts them at a disadvantage when they get to the breeding grounds. But this kind of thing is likely to happen all over the place. So decline in insect populations is going to be bad for birds across the board.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the more interesting illustrations in your book is a picture of a billboard that you bought of warning of the dangers of wind turbines. What's your concern?

Kenn Kaufman encourages thoughtful planning on the placement of wind turbines in his book. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, I have to say, I'm not opposed to wind power, I don't think it's a bad thing. I think wind power is a really important source of renewable energy. And it's really worth developing, I just think the location is important. If you put up a wind turbine, any place, it's likely to kill a few birds. And that's just the way it goes. We can't take all the things threats to birds out of the environment. And it's so important to have green energy that, you know, we'll accept the fact that there's going to be some mortality of birds with these big spinning blades. But there's some places where wind turbines are going to kill so many birds that it's just not worth the risk. And one of the types of places where wind power is really a problem is in this major stop over habitat for birds. Like where we are on the shore of Lake Erie, there are all these nocturnal migrants coming in. They're landing in the dim light just before dawn, they're taking off in the dimness, just after it gets dark. And so they'd be going right through the sweep of these rotor blades on the wind turbines. Whereas a wind turbine out in the middle of farm country someplace, might not really be that damaging for bird life. Here on the lakeshore, in the middle of this stop over habitat, it could really do serious damage to populations of these long distance migrants that are already facing so many threats.

CURWOOD: For those people who live at a stop for birds on their migratory path, what can they do to make their local environments more welcoming and helpful to these traveling birds? Keep your cats inside, grow native plants, eliminate or at least reduce the use of chemical pesticides? And anything else, Kenn?

KAUFMAN: I really appreciate that question because that's something that's relevant everywhere. Just supporting conservation efforts in general, supporting protection of native habitats. There are cases where just by voting on certain issues, people can affect what happens with wildlife habitat in their local area. It's worthwhile for people to educate themselves about the issues and pay attention to what policy changes are going to have an impact on bird life.

Kenn Kaufman is a renowned birder and naturalist (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

CURWOOD: Before we go, what do you hope readers will come away with after reading your book?

KAUFMAN: I'm hoping that people who read the book will learn something about the science of migration. But if I, if people were to come away with one thing from it, I hope they would just be taken with just the sense of wonder. Just the fact that this is an amazing, miraculous thing that we're seeing. And it, it happens everywhere. So it's a true miracle that happens twice a year, and that you can witness just about everywhere. And I think the more you learn about it the more magical it becomes. And, so, just the blend of science and magic is the one thing that I hope that people will take away from the book.

CURWOOD: Kenn Kaufman's book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's always great to talk with you

Related links:

- Kenn Kaufman’s Official Twitter

- More about Kenn Kaufman

- Audubon | “Kenn Kaufman's Backyard Is One of the Best Spots to Witness Spring Migration”

[MUSIC: Brian Rolland, “Lioness” on Long Night’s Moon, 2000 On The Full Moon Productions]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth