February 26, 2021

Air Date: February 26, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

No Power For The People In Texas

View the page for this story

The most frigid days in Texas since 2011 killed dozens as it crippled the state’s power grid , led to acute water shortages and underscored the risks of extreme deregulation. Gretchen Bakke, a cultural anthropologist and author of The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the recent catastrophic outages in Texas and how America’s electric power system has grown more unstable in recent decades. (14:55)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the first successful cloning of a US endangered species, the black-footed ferret. Next, they unpack the double-trouble of drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), and the role of the Porcupine caribou herd to trim vegetation and maintain a bright albedo. Finally, they travel back in history to March 1, 1954, the day that the US detonated a massive hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll. (04:18)

Note on Emerging Science: Wild Bees a Boost to Crops

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

For this week’s note on emerging science, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman discusses a recent study on the importance of native wild bees in agriculture. Native pollinators boosted yields for every crop studied, even on farms that use managed honeybees. (01:32)

A Civilian Climate Corps

View the page for this story

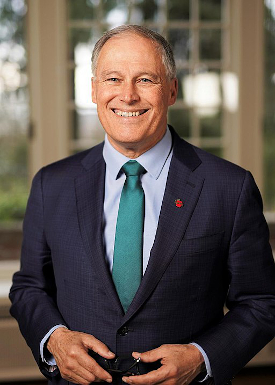

President Biden has directed the federal government to plan a Civilian Climate Corps loosely styled on the New Deal CCC that put millions to work building trails and park facilities during the Great Depression. Washington Governor Jay Inslee joins Host Steve Curwood to share a vision for how a climate corps could aid conservation, combat climate disaster, and help save energy while harnessing the energy of youth volunteers in America. (11:00)

Searching for Life on Mars

View the page for this story

After a spaceflight of over 200 days, NASA’s Perseverance rover has landed safely on Mars. Perseverance is the first part of a three-phase mission designed to find signs of ancient life on the red planet, and return samples to Earth by the 2030s. Sarah Stewart Johnson, a planetary scientist at Georgetown University who has worked on the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rover missions, joins Host Steve Curwood for an update. (15:49)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210226 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Gretchen Bakke, Jay Inslee, Sarah Stewart Johnson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A call for a civilian climate corps to help the American yearning to address the climate emergency

INSLEE: I'm old enough to remember the John F. Kennedy "Ask not what your country can do for you", this is a little bit of that. It can connect people to a larger national purpose. There's like a, you know, just a huge dam holding back energy, we want that energy to be released. And I think this climate corps is a way to do that.

CURWOOD: Also, data is pouring in from the Perseverance rover which recently landed along an ancient river delta on Mars.

JOHNSON: We have so little left of that ancient history here but on Mars the past is everywhere. There are all of these incredibly old rocks and this delta is from a period when we think that Mars was much more habitable than it is now.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

No Power For The People In Texas

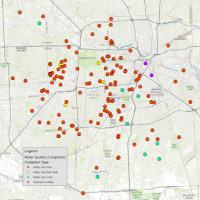

The sudden deep freeze in Texas burst many pipes, putting safe drinking water in short supply. This map shows water quality complaints made to Houston's Public Works department on February 23 and 24, 2021. (Photo: Houston Public Works)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Ice was late to form last October in the Arctic Ocean, and the unusually warm air helped magnify dips of the polar jet stream, ultimately blasting the region that includes Texas with the coldest air in a decade. With a low of 2 degrees Fahrenheit, electric power plants in Texas froze up, leaving millions without electricity to heat their homes. Dozens died, some freezing to death and others killed by carbon monoxide as they tried to use vehicles and barbeques to keep warm. Frozen pipes also burst, making water scarce and ruining homes. Climate disruption is one factor for this deep freeze disaster, but the power grid of the Lone Star state was the most direct killer. Texas has its own electrical grid, independent of the rest of the country and federal regulations, so it couldn’t import much power from nearby states, and Texas doesn’t require its power plants to be prepared for extreme cold. The state is now recovering and to explain more I’m joined by Gretchen Bakke. She is an anthropologist and author of The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

BAKKE: Thank you for having me back.

CURWOOD: To what extent is the disaster in Texas linked to the level of privatization we have for electricity in the United States?

BAKKE: So the disaster in Texas, I think you could say there's several reasons. One is that it was too cold for a system which was not designed for cold. And they had a big freeze in 2011 and there's a lot of critique against them for not having taken really basic steps to make their infrastructure, what we call hardened the infrastructure to protect it a little bit more against cold weather, but it is the third hottest state in the country. So a second reason in Texas is that there is a lot of energy trading that is happening there. So it's not necessarily that it's for profit companies, we have a lot of for profit companies in the US, you know, if you live in Chicago and Boston and DC and LA, you're paying into a for profit company. So in Texas it's not necessarily that the for profit company is there it's that you have a radically deregulated electricity market upon which it's easy to make money through quick trades and you have a much more ferocious trading market in Texas than you have in other parts of the country. This is not a cause for the grid going down. This is a place where we can really say that Texas is deeply committed to a certain kind of American freedom that allows for a lot of risk and a lot of profit, especially related to energy endeavors. But at the same time, because this trade is happening at such a rapid rate and with so many players there is more risk for owners of infrastructure to invest even small amounts of money into that infrastructure. Because pennies here and pennies there can mean big losses and big profits in various ways as the money is transacted across the grid.

CURWOOD: Let's talk for a moment about the very nature of electricity. I mean, to me, it's kind of amazing. It's only an instantaneous phenomenon if I understand that correctly.

WCK partner restaurant Knife & Chef John Tesar delivered soup, rice with beef, fruit & water to Ivy and Sunchase Apts this afternoon—a complex that houses immigrants who recently arrived in Dallas! They’ve been without power & have water damage from burst pipes. #ChefsForTexas pic.twitter.com/JRvqvxMpMM

— World Central Kitchen (@WCKitchen) February 20, 2021

BAKKE: Yeah, so we use it fresh, you can't really store it. And the minute I say that people are like no, but batteries. And it's like, yeah, batteries aren't storing electricity, right? Batteries are using electricity to create a process that when you reverse it you get roughly the same amount of electricity back. And it's the same thing if you use electricity to pump some extra water up a hill, and then you let that water roll down later through gravity and it makes electricity on the way back down again. But we aren't ever storing electricity. Electricity isn't something even though we trade it, we can't treat it like an object, it's a force. And it would be like if somebody said to you like could you put some gravity in this box and keep it for me and I'll use it later, right? And we say, well, that doesn't make any sense. But somehow with electricity we don't think that or we don't realize that. So we make it and we use it within about a minute. And that means that every time you open up your refrigerator and the little tiny light in your fridge comes on somewhere more electricity is being made. And so you always have to balance the system, what is being asked for, and what is being produced have to be in balance to about the minute. And one of the things that that happened in Texas is that it got really cold and everybody turned up their heat. And so it's this very simple relationship between more electricity is being asked for and there's nothing to turn up.

CURWOOD: So the Biden Harris administration has announced that it's going to push the United States towards carbon pollution free electricity by the year 2035. And right now, on the order of 30% of us CO2 emissions come from electricity generation. So what are the kinds of steps that the administration would need to take to achieve that goal and, and also, at the same time, increase climate resilience throughout the electric infrastructure in the US?

BAKKE: I think the looming problem in this proclamation is what we're going to do about cars, right? Because 30% of our CO2 emissions are coming from electricity that's down from what it was. And it's falling steadily, because you can't make electricity more cheaply than you can with wind or solar power.

CURWOOD: Yeah, let's talk about the numbers. I think the Zero Carbon Action Plan looked that if you wanted to get net zero emissions by the year 2050, we would have to increase renewable generation capacity from the one terawatt, I think to about three terawatts. So that means increasing renewable energy generation capacity by, you know 100 gigawatts every year, obviously, mostly from wind, and solar. And, you know, good sized nuclear plant or a coal fired power plant might generate a gigawatt. So that's a lot of generation capacity that we need to get from the renewable sector.

Fam spent the afternoon for refugees who had no power water all week. Grocery boxes, hot meals, blankets and waters packed and distributed for 300+ families thru @marufdallas. Good grounding for all of us. Find an org and donate please, lots are still hurting in Texas. pic.twitter.com/9Cv63l4X3j

— Neghae Mawla, MD (@NMawlaMD) February 21, 2021

BAKKE: It's a lot of generation capacity. And when you see it that way it's actually opening up Pandora's box of reforming how it is that we relate to electricity and to the electricity system, because the logic of fossil fuels was people in America, and companies in America can use as much electricity as they want, whenever they want and the price will be fair. And we will produce that electricity as they wish at whatever quantity. And one of the things that begins happening when you can't turn up production because if you have a bunch of wind power, the wind is blowing that's what you got, right, you can't turn it up. So if you can't turn up production, then you have to say okay, what can we do? Turn down consumption. And as soon as you start talking about turning down consumption, you have to say, okay, how do we do that? Well, if you have solar panels on your roof and you're in a little miniature grid, which can connect and unconnect, from the bigger grid with maybe three or four of your neighbors, you could say, for price, because this is America, right? For price, we will remove our demand from your electricity grid right now. And we will just use our battery backup power, we'll use the sun because it's shining, you know, we'll turn our free refrigerators off at night, we don't really need them, we'll go to bed, we'll just turn the whole thing down. It's a radically new idea about how you would balance the system, not always by turning up power generation, but by actually turning down demand. And that asks us to be different kinds of electric citizens. And nobody's quite doing that yet but you could see the worry on the horizon. Because we can't just build out the generation, all this solar, all this wind as if we were replacing fossil fuels. They're just different entities. The wind is not a lump of coal, it works differently and it has makes different infrastructural demands upon the system, and upon us as users of the system and designers of the system.

CURWOOD: How can you sell that it sounds like a step backwards for people?

BAKKE: Well, you could sell it by saying, hey in Texas if you'd had a solar panel that you'd been able to use not to sell electricity onto the grid, but just use for yourself or for your neighbors, who would have had power for the last week. I think you could sell it like that.

CURWOOD: Stability, consistency...

BAKKE: Freedom, independence...

CURWOOD: And not being vulnerable to predatory trading practices.

BAKKE: Yeah. And early on, one of the big selling points of home solar systems was that rather than having this very random electric bill that never makes sense to anybody, like literally never makes sense to anybody. There’s no one I know, that looks at their electric bill and says, I get it, like, I know what I being charged for. Right? Doesn't make sense. So rather than getting this thing that changes every month, for reasons that don't quite make sense, you're paying essentially a mortgage on the solar panel. And then you have a stable 20 year set of payments that you're making. And you don't feel this kind of panic about what is my bill this week? What is my bill this week? What is my bill this week? And a lot of people opted inn just for that just for the security, not nothing to do with being green or saving money or any of that just like I know what my bill is going to be.

CURWOOD: Yeah, like the folks in Texas who woke up latter parts of the catastrophe with many thousands of dollars, charges for household used turning on the lights literally, because of the deregulated variable price structure.

BAKKE: Yeah, absolutely. And those people they opted into paying the real time rate for electricity as opposed to a standardized rate averaged over the year. And that's also something that is to my knowledge only allowed in Texas. So there's all kinds of market volatility happening and other places but we don't pay it, right? It gets averaged into our bill, we pay our whatever the same amount every month, you know, and it changes from year to year little by little. But in Texas, a consumer can opt into that. And then suddenly is charged $9,000 a kilowatt hour right. And they're happy their lights were on but that's not a refrigerator. You'd be like unplugging in the fridge in that situation like you do not want it on, you do not want it on.

CURWOOD: So years ago in America, before the 60s really almost all electric power generation was done as, quote, a public service, it was either a municipal power supply or if it was a private company, they were highly regulated as to how much they could charge and what they would build and they would get, you know, a flat fee on top of their expenses. We've gone away from that, what if anything, did we lose in the process of taking the electric grid out of the realm of being a public utility, like the road and making it into a private service.

BAKKE: So what one of the things we got from that process was dynamism. Because the utilities were so highly regulated. And because the cost of making a kilowatt hour was completely unlinked from their point of view, from the amount of money they made on a kilowatt hour, they were really outside the market economy for almost 50 years. So they didn't know about customer service, they didn't really know how exactly you might make power, the best way, they just sort of thought you just grow and build and grow and build and grow and build this is how we've always done it. And what happened under Carter was this move to say maybe bigger power plants further and further away from the city is not actually the smartest way, maybe we can undercut the utilities. And Carter opened up the possibility for small power producers to sell their electricity into the grid that was run by these larger utility companies. And from that, we got the renewables revolution. That's where it came from. The other thing that happened almost simultaneous to that was this radical deregulation under Reagan. And that then allowed the trade in electricity to begin to try to mimic the trade in other goods. Even though electricity doesn't work in the way that other goods work, the trade and electricity sort of formally became something that looked like the trade and anything. And one of the things we got from that is a chatier system.

Gretchen Bakke is a cultural anthropologist and author of The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future. Gretchen Bakke is a visiting professor of anthropology at the Integrative Research Institute on Transformations of Human-Environment Systems at Humboldt University in Berlin. She is also a member of the Anthropocene Working Group at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. (Photo: Courtesy of Gretchen Bakke)

CURWOOD: Gretchen Bakke how likely is it that we would have pretty much universal electricity access in the US without what happened during the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the bid to electrify America?

BAKKE: There is no way that we would have universal electricity in the US without the government having decided that people were you could not make a profit off of them, rural people and poor people should have the same technological advantage. And the government decided that and the utilities have to abide by it at their own expense, they have to serve rural people, and they have to serve poor people. We tend to think in America of electricity as a human right. I've seen this more and more, especially among the young, you have potable water, you have clean air, you have electricity. But electricity is not a natural right. Electricity is something that we all have access to, because the government at one point in time decided that this was an American value linked to equal opportunity and not actually driven by profit motive. In fact counter to profit motive. Here are people which must be served from whom one can not earn anything.

CURWOOD: Gretchen Bakke you're an anthropologist, you're not an engineer or finance person. And yet, in many respects you're a go to expert on the issues of the grid. What does your discipline tell us about other things we might need to know going forward in this new world where we're trying to wrestle with the climate emergency and how we handle things like energy?

BAKKE: I think anthropology tells us that ideas that we have about the world create the world that we live in. And so if you take something like an electrical grid, this is not the product of physics. This is the product of a bunch of ideas about what it is to make money, what it is to run a business, what it is to have a social good, what it is to be modern. And we put those ideas into this thing, and that's happening over and over and over and every element of our lives.

CURWOOD: Gretchen Bakke is a cultural anthropologist. Her book is called The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and our Energy Future. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BAKKE: My pleasure. Absolutely.

Related links:

- Learn more about cultural anthropologist and author Gretchen Bakke

- Listen to Living on Earth’s interview with Gretchen Bakke on her book The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future

- The Washington Post | “The Grid Leaves Us Powerless”

- Yale Environment 360 | “How Biden Can Put the US on a Path to Carbon-Free Electricity”

- Bloomberg Green | “Biden’s Plea to Remake Grid Gets a Boost on Texas Power Crisis”

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai, “Kokopelli Wind” on Canyon Trilogy, by R. Carlos Nakai, Canyon Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –we’ll look at the cloning of an endangered species.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, “All or Nothing at All” on Ballads, by John Coltrane, Impulse!/Universal Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The black footed ferret became one of the most endangered species in North America, thanks to a government program to poison prairie dogs, a primary food for these ferrets. (Photo: Ryan Hagerty, USFWS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Well, it's that time of the broadcast when we take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, how are you doing? And what are you going to talk to us about today?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. We're going to travel out to the Great Plains of the United States on the news of the first cloning of a US endangered species, the black-footed ferret.

CURWOOD: Okay, so what do you have to tell us?

DYKSTRA: This happened in December, but it was just announced a week ago. Scientists cloned the black-footed ferret from the genes of an animal that died over 30 years ago.

CURWOOD: Endangered, why are they so endangered?

DYKSTRA: Black-footed ferrets, known to me as BFFs, although I think that's been claimed elsewhere in social media, were nearly wiped out largely from a widely known program of the Animal Services Department of the US government. The prairie dogs were poisoned. Black-footed ferrets are adorable, but they're also fierce predators, and prairie dogs were their main food source.

CURWOOD: Yeah, they're not the best smelling animals either, those ferrets, but they are pretty adorable. Okay, Peter, let's take a look around and tell me what else you see beyond those headlines.

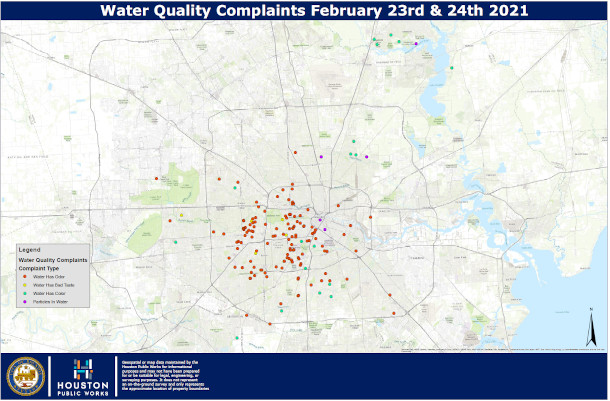

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is located in Northeastern Alaska and consists of 19,286,722 acres, making it the largest national wildlife refuge in the United States. Area 1002, the area under consideration for oil exploration, is a summer calving and feeding ground for Porcupine caribou. (Photo: EIA, Flickr, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: We'll go from the Great Plains up to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) in Alaska. It's been a political football kicked back and forth between environmentalists, oil executives, and the state of Alaska for over 30 years. In the dying days of the Trump administration, they carried out a lease sale in ANWR. Oil companies were less than enthusiastic about it. But if oil drilling is started in ANWR, scientists are concerned that it will have a double impact on the area's carbon emissions.

CURWOOD: And how would that be?

DYKSTRA: Well, one, of course is that you're drilling for oil, and if you're going to use it, you're impacting carbon. But the other one is that oil drilling in the same place as the herd of 150,000 Porcupine caribou come in late spring and summer to feed. If it changes their behavior, and there's less feeding on the vegetation, then the shrubs that grow in late summer and spring in the midnight sun will grow higher. And if they grow higher, they'll be a darker surface. That's known as albedo. The white snow reflects heat, the darker shrubbery would absorb it. And the whole process of melting the permafrost in that part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge happens quicker.

Porcupine Caribou migrate some 1500 miles from Alaska to the Yukon border and back each year and are the primary sustenance for the Gwich'in and First Nations of Alaska. (Photo: Gary Braasch, NWF, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a look back in history now. Tell me what you see there.

DYKSTRA: March 1, 1954, the US detonated a massive hydrogen bomb, the biggest ever at the time, in the atmosphere at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. The crew of a nearby Japanese fishing boat called the Lucky Dragon is felled by radiation sickness. One of the crew dies, the other 22 are sickened, even as they brought their nine tonnes of presumably radioactive tuna back to market in Japan.

CURWOOD: Yeah, the world I don't think was so happy about our explosion there at Bikini in March of 1954 as I recall.

DYKSTRA: Not only was it a big factor in banning atmospheric tests in the early 1960s, but if you've ever watched the original Godzilla movie, something based on the Lucky Dragon's disaster, is how the movie, first of 22 Godzilla flicks, got its start.

CURWOOD: And this wasn't exactly a small bomb that they used at the Bikini Atoll on March 1 of 1954, right?

DYKSTRA: That Bikini blast was 1000 times as strong as the blast that wiped out Hiroshima.

Between 1946 and 1958 the United States carried out detonations of 23 nuclear weapons on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The inhabitants of the Marshall Islands were exposed to harmful radiation and had to be evacuated three days after the explosions. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website, that's loe.org.

Related links:

- AP News | “1st Clone of US Endangered Species, a Ferret, Announced”

- Yale Environment 360 | “Why Drilling the Arctic Refuge Will Release a Double Dose of Carbon”

- Stanford Magazine | “What Bikini Atoll Looks Like Today”

[MUSIC: Fiamma Fumana, “Angiolina” on Onda, by Alberto Cotica and Jessica Lombardi, Omnium Recordings]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, the promise of a Civilian Climate Corps for sustainability and stimulus, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note on Emerging Science: Wild Bees a Boost to Crops

A male bumblebee flies toward a flower, ready to extract nectar. Wild bees such as these make up a significant share of crop pollination even in farms that use managed honeybees. (Photo: Sffubs, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

LYMAN: Although many farms in the United States use managed non-native honeybees to pollinate crops an analysis of seven crops in North America shows wild bees, such as bumblebees, contribute to crop pollination too, even on farms that utilize managed honeybees. A new study estimates that wild bees add at least 1.5 billion dollars in total yields of six fruit crops including watermelons cherries, and apples. To measure the contribution of wild native bees on pollination, researchers monitored bee visits to flowers at 131 commercial farms across the United States and Canada. They found farms often didn’t have enough honeybees to get the maximum crop yield, and native wild bees were supplementing pollination. Native pollinators boosted yields for every crop studied and added more than a billion dollars’ worth of apples, 145 million dollars’ worth of sweet cherries, and 146 million dollars’ worth of watermelons. All bees, both native and non-native can be sickened and killed things like pesticides and diseases. that means threats to wild bees could decrease farm profits even if the farmers are using stocked honeybees to pollinate their crops. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

Science News | “Wild Bees Add About $1.5 Billion To Yields for Just Six U.S. Crops”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

A Civilian Climate Corps

A Student Conservation Association crew is all smiles as they work to restore a trail in the popular Paradise area of Mount Rainier National Park (Photo: Kevin Bacher / NPS, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

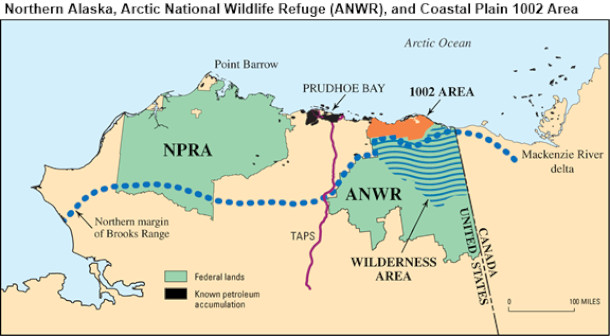

CURWOOD: A Civilian Climate Corps is part of President Biden’s plans to address the climate crisis. The modern CCC harkens back to the Civilian Conservation Corps created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s. FDR’s CCC put some 3 million men to work in conservation efforts, and yes, they were just about all men. They planted some 3 billion trees, constructed trails and shelters in parks across the country, and built thousands of fire towers. Much of that work can still be seen today. A job in the CCC earned a young man 1 dollar a day plus food and housing. And it put money in the pockets of families during the depths of the Great Depression and was cheered as a resounding success at the time. During one of his famous Fireside Chats in May of 1933 FDR explained how the CCC would help the nation.

PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT: In creating this civilian conservation corps we are killing two birds with one stone. We are clearly enhancing the value of our natural resources and at the same time we are relieving an appreciable amount of actual distress.

CURWOOD: Today a Civilian Climate Corps could put people to work reducing the risk of forest fires, restoring wetlands, planting trees, and weatherizing homes both in the United States and abroad. During the Democratic primary, several of President Biden’s opponents also proposed a climate corps. Among them was Washington state Governor Jay Inslee, who joins me now from the capital in Olympia. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Governor!

INSLEE: Thank you.

Civilian Conservation Corps members at work c. 1933. (Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So let's say that you were to take a look at your own state of Washington for some examples of the kind of work that the CCC would do. You've had horrendous wildfires, so I imagine you're very interested in thinning the forests, the fuel that can add to those. Where else might it be especially useful?

INSLEE: Everywhere. This is a ubiquitous opportunity, because anywhere there's a house, there is an opportunity to reduce energy wastage. And that's the first place you get clean fuel, the very cheapest, first, most productive fuel, clean energy is always stop wasting it. So helping people rehab their houses, get more insulation into their homes, starting with those who are in low-income homes, who frequently are living in places that just waste humongous amounts of energy, so these poor folks are trying to make huge energy payments to the utility company. When instead, we can have a young person come in and rehab the home, do these kind of retrofits that people can do with relatively modest amounts of training. Every city, every suburb in the country has these opportunities right now. And then a part that I think hopefully is more focused on vocational skill development, career development. You kind of think, what can I do to something, to really focus on a long term career, not just in the climate corps. That might be as exotic as, you know, learning how to maintain electric vehicles, because that's we're going to be driving ten, twelve years from now, almost, if not exclusively, predominantly. So starting those kind of career paths, helping people you know, have an income while you're learning that. This is terribly exciting for the long term vocational future of people.

CURWOOD: So this all sounds great about the CCC, but you know, it can't be cheap, especially if corps members are paid a good living wage for their work. How much is it going to cost to have this Civilian Climate Corps? How much money do you think Congress needs to appropriate?

INSLEE: This is a scalable issue, $1 is good, and $100 million is better. And so I don't think there's a minimal or a maximum, if you will, it's just what can fit in with the other priorities of the federal government. But I think that once you see it, it will succeed like the AmeriCorps has succeeded. The very first vote I took as a member of the US Congress was to establish the AmeriCorps program. And I go around my state, and I see these kids -- and I say, "kids", I mean, they're mostly young adults -- who are doing this work. And whenever you see them, they all have something in common. Doesn't matter what race they are, doesn't matter if they're urban or rural. They all have a big smile. Because they're doing something they believe in. And they think they're helping people in their community. And they're learning something. And it's unfortunate that Republicans have tried to kill this project, maybe every year since I was in Congress, first in 1993. And they have failed, and they have failed because people in their communities understand what this good work means to their communities. And you had all these people who, it was important in their life's development. I think that'll be the same about the climate corps, it's built somewhat on the same principles, with a more focused message, to connect people to this worldwide challenge.

An Americorps crew at work doing restoration at Joshua Tree National Park, April 2018 (Photo: Hannah Schwalbe / NPS, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was going to ask, you know, many young people I speak to are desperate to do something to deal with the climate emergency, which they see as this humongous freight train barreling at them out of the future, and no way to jump out of the way.

INSLEE: Well, you are right, particularly the upcoming generation gets this big time, there's no question in their minds that this is a huge threat to their futures. You know, I'm, I'm old enough to remember the John F. Kennedy "Ask not what your country can do for you", this is a little bit of that. It can connect people to a larger national purpose. And I hear this as well, how do I plug in? What do I do? Where do I go, you know, what, you know? And this is just perfect to capture that huge energy that's out there. There's like a, you know, just a huge dam holding back energy, we want that energy to be released. And I think this climate corps is a way to do that. It will help as well build, you know, public support, political support, for some of the other things we need to do to get people visibly involved in this mission statement as well. You know, somebody comes up and says, this is a hoax, or this is going to hurt jobs, you say, look at all the jobs we're creating through this mechanism. So it's a, it's a win-win-win, in my book.

CURWOOD: So how can and should a program like this be designed to work in a smart way with the private sector so that you don't hear concerns about displacing already existing jobs?

INSLEE: Well, I think that, you know, these are not going to be the highest paying jobs in America. So I don't think you have to worry that much. We want to pay a living wage. But I don't, I really don't believe that's a viable concern. These are going to be answering things that we have not been able to finance or the market has not been able to finance yet. These are things that aren't happening today. So it's not like we're displacing existing jobs. But to the extent people are concerned about that, you have good community input in designing the programs, you develop as many partnerships as you can. So that if you have one corps volunteer, they serve multiple, you know, masters, they can work with a municipality, they can work with a state forest at the same time. It's just all about partnerships.

The CCC constructed the Harney Peak fire lookout tower in the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1939. (Photo: MisterSquirrel, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So the original Civilian Conservation Corps under FDR reinforced some social injustices, and even segregated black and white corps members into different camps, and there weren't a whole lot of women that were involved in this. How can this new CCC help progress towards greater equity in our society?

INSLEE: Well, you've put your finger on a very important point. One is the most obvious one, which is economically to give people more economic opportunities. And I'm convinced it will do that big time. You know, the young folks in a, in an urban area who don't have a family connected, to inherit the family business are now going to be able to get a great career. So that's a good thing. But there's another thing too, that's important to me. We have so many children, urban children particularly, who've never had experiences in the natural world. And giving them these experiences in a vocational setting is life changing for people. And so giving folks who've really never spent a night in a sleeping bag or a tent, never handled a polaski or a hoe or a shovel. My dad and mom used to revegetate alpine meadows on the slopes of Mount Rainier during the summer, they ran a group called the Student Conservation Association. And we, and they were kids, mostly from the East Coast, who came out to Mount Rainier National Park. And my dad, he told me the first week he did this, he was astounded because he'd get these kids who didn't know how to do a shovel. They wouldn't know where to put their foot on the shovel! And my dad kind of chuckled about that. But once they got that shovel in their hands, and once they spent a night in the tent, they were conservationists for their whole lives. I met a guy who was in my, one of my dad's programs, when I was running for governor, I don't know, about six, eight years ago. And you know, he'd been a dedicated environmentalist who'd funded a lot of good causes because of that project. And I think we're gonna have the same impact in people's lives, once they get a little taste of being outside.

CURWOOD: Now, you folks in the West have a lot of opportunity, a lot of public spaces, some big national forests and such. What suggestions do you have for folks in the East, in the more urban part of America? How might those cities and states get involved in this?

Washington Governor Jay Inslee ran on a climate-centric platform during the 2020 Democratic presidential race. (Photo: Office of the Governor, State of Washington, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

INSLEE: Well, there's outdoors in the East, if you go looking for 'em. And you don't have to be 100 miles from an urban, you can find a marsh wren and a great blue heron a couple miles, you know, from Manhattan. I live five and a half miles from downtown Seattle. And there's a little pocket, it's about maybe 16 acres, fairly close to where I live. It's a paradise! I go in there, and I'm as happy as I was in the middle of Grand Canyon. Because I can get a feeling of nature in a small place. And one of the ways this group I think can help is in education. So I can envision, if you were in this corps someday, working in this park, bringing in students to educate them about the life forms in their little park. And there's a lot of life right underneath our feet. And it's kind of thrilling. This little wren, I was in this little park the other day and this little wren, I'd never seen it before, comes skittering in, and it turns out, it's either a marsh wren or a winter wren, I never did figure it out. And kids love this. They just, they connect to this. You give a kid a little spade and ask them to dig up a little mound of earth and tell you what they find in there, and talk about how the climate can change that. If you have kids do a little pH test to test the acidity of a little pond, they go, they go crazy about that! And they become little environmentalists for the rest of their lives. That's what this corps can do, just even in a pocket park. You can connect to the whole rest of the world in something like that, if you have somebody showing you the way.

CURWOOD: Jay Inslee is the Democratic Governor of the State of Washington. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

INSLEE: You bet! We'll see you when we open up the corps, I hope you'll be there for the first group doing great work.

CURWOOD: I'll bring my shovel.

INSLEE: Alright! Take care, be well!

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Biden’s New Conservation Corps Stirs Hopes of Nature-Focused Hiring Spree”

- Read Governor Jay Inslee’s Call to Action for a Climate Conservation Corps from May 2019

- Grist | “This $9 Billion Plan Could Bring Biden’s Conservation Corps to Life”

[MUSIC: Chick Corea + Gary Burton, “Love Castle” on Native Sense, by Chick Corea, Stretch Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Searching for signs of ancient life on Mars. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Maeve Gilchrist and Viktor Krauss, “Farika” on Vignette, by Maeve Gilchrist, Adventure Music Records]

Searching for Life on Mars

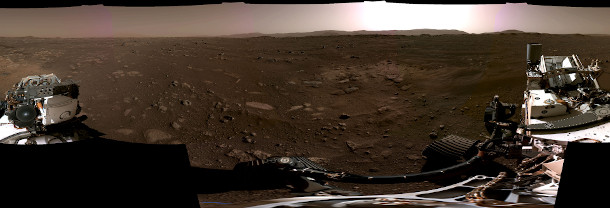

A panoramic view of Perseverance’s landing site on February 18, 2021. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

After a spaceflight of over 200 days, the Perseverance rover landed safely on Mars on February 18th.

[SFX touch down confirmed, Perseverance safely on the surface of Mars ready to begin seeking the signs of past life. (cheering)]

CURWOOD: Venus is our closest planetary neighbor, but it’s a hothouse of nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit and shrouded with clouds. Mars is much further away, but with a bit of atmosphere and morphology that suggests ancient rivers and oceans. So, NASA designed the Perseverance rover to search on the Red planet for signs of ancient microbial life, and perhaps help answer the enduring question of ‘are we alone in the universe?’ Perseverance touched down softly in an area that appears to have been at the edge of a Martian ocean, some three and a half billion years ago. Back when the robot launched we with spoke with astrobiologist Sarah Stewart Johnson. She worked on the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rovers and wrote the book The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. And she’s with us now for an update. Sarah, welcome back to Living on Earth!

JOHNSON: Steve, thanks so much for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, the last time we talked to you, Perseverance hadn't even launched yet. So how did the launch and the flight and landing go for this mission? Of, course many of us saw on television, but from your perspective, as a professional in the business, how did it go?

JOHNSON: Oh, just spectacularly well, it was just flawless. I mean, the high definition video of the landing has now been released. And I really hope your viewers have a chance to watch it, it will blow their minds. You know, NASA sent this spacecraft on a journey that was 300 million miles. and Perseverance came blazing in to the top of the Martian atmosphere at 12,000 miles an hour. And over the course of seven minutes, what we like to call the seven minutes of terror, it slowed down to just two miles an hour, it landed perfectly unharmed, right next to this exquisitely preserved ancient River Delta, which is the main science target for the mission. And I guess that all just kind of speaks for itself,

CURWOOD: River delta? From how long ago?

JOHNSON: So, it's over three and a half billion years old, which is one of the most ancient times on Mars. And when we think back to our own ancient past, so much of that has been lost because of plate tectonics, because of fluid erosion. It's almost like we've swallowed our past plate by plate, we have so little left of that ancient history here. But on Mars, the past is everywhere. There are all of these incredibly old rocks. And this delta is from a period when we think that Mars was much more habitable than it is now.

CURWOOD: So this means we're gonna find life there, maybe? Kind of? Hoping? What are the odds?

JOHNSON: You know, I'd still say it's a bit of a long shot, but we're really hoping. So one thing to know about Mars is that, you know, Mars was a lot more similar to the earth around the time that life was getting started here. And so it's a big open question, you have the same sort of planet, the same types of starting materials, we found the building blocks of life, the organic molecules from which our own life is built. We found all the essential elements for life as we know it on the surface of Mars. We know that there were lakes and streams, maybe even a Great Northern ocean that existed on the planet early in its history. And so it's kind of an open question, did life you know, start twice? Did lightning strike that right over at the planet next door, or not? And so I think that that's why it's so exciting to look at Mars, because we've never found another planet, in the universe that's more similar to Earth. But still, you know, we have to, we have to do the hard work, we have to get these samples back to earth and really scour them with whatever we've got. You know, I like thinking back to this famous line that Carl Sagan once said, you know, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Sample tubes, here being loaded into the Perseverance rover, are meant to house the samples of Mars as they are collected and returned to Earth. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So this is an extraordinary project that the Perseverance is a part of. Briefly, tell me, how are you going to get these samples back to Earth from Mars?

JOHNSON: So it's a great question. So what Perseverance is doing is kicking off this breathtakingly ambitious campaign to collect these samples of Mars and bring them back to Earth. And it's gonna take some time and some additional missions to actually get them back. So it's gonna be at least a decade. And the idea is that there will be three missions, you know, some of the details are still being worked out. But this first mission, Perseverance, will spend the next two years exploring this place called Jezero Crater. There are all kinds of exciting astrobiological targets that the rover will go up to and explore and characterize. And it will collect samples, at least 20 of them, hopefully double that number. But they're about the size of a piece of school chalk each, and it will cache those. And those samples will be left on the surface for the next mission to come along. And that mission will be a fetch rover that will pick up all of those samples and put them into an ascent vehicle, which will power on up to orbit. And then another mission will come and take those samples up from orbit and carry them home to Earth. And the best possible timeframe is we're looking at the 2030s to to get them back and of course it is just, it's an incredible undertaking. You know, you may have heard the term 'go big or go home'. You know, a lot of folks in the Mars community try to describe this as 'go big and go home'. But for the community of astrobiologists, I have to tell you, it's just incredibly exciting, the idea that one day, you know, I might be able to hold these various samples in my hands, you know, that we could get these back into our laboratories, these very carefully selected samples that we think might hold those echoes of ancient life. I mean, there just couldn't be anything better.

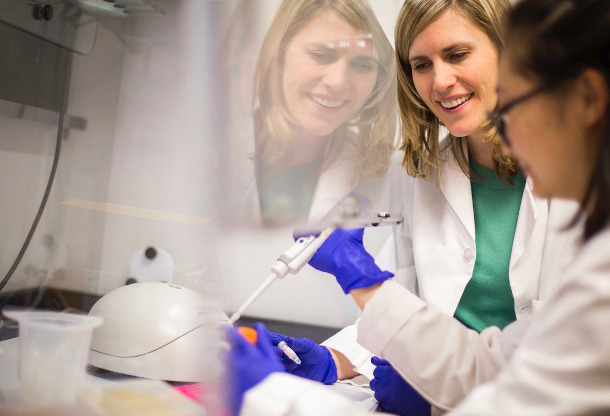

CURWOOD: So what could be in those samples to tell you about life? I mean, I gather we're talking about the fairly microscopic, or certainly small, forms of life.

JOHNSON: That's right, Steve. So it's really only been in this last chapter of our history here on Earth, that we've even had multicellular life, but microbial life, simple life, has dominated our own biosphere for most of our history. And that's the main thing that we're thinking we might find on Mars. And what we're looking for are called biosignatures, or traces of life, really anything that could denote a biological origin. And you've seen fossils before, you know, we didn't get body fossils here on Earth again till recently. But there's a molecular version of that, there are molecular fossils, where we can see with particular types of organic molecules, different chemical constituents that would potentially be very indicative of life. We could also potentially find biogenic minerals or structures, types of ancient microbial mats that might have been preserved in the lake that was in Jezero Crater. And the surface of Mars has become a pretty hostile place for life to exist, there's a really difficult radiation environment that life has to contend with. It's almost like a sterilization chamber right at the surface of Mars. And so we're really focused mostly on ancient life. And those samples, though, deeper down in the subsurface, that's a place where current life might actually still exist. And so that's one of the exciting things about another rover that's on the horizon, a mission from the European Space Agency, called the Rosalind Franklin rover, which is going to drill down through that thick basalt a couple meters into the subsurface, where you'd have a lot more protection from that dangerous radiation.

Now that you’ve seen Mars, hear it. Grab some headphones and listen to the first sounds captured by one of my microphones. ????https://t.co/JswvAWC2IP#CountdownToMars

— NASA's Perseverance Mars Rover (@NASAPersevere) February 22, 2021

CURWOOD: And so when does that land? And how far away from Perseverance will that activity be going on?

JOHNSON: So it's gonna land in 2023, in a place called Oxia Planum, and too far away, unfortunately for those rovers to rove toward each other and meet one day.

CURWOOD: What else is the Perseverance project doing? Aside from getting these samples near the spot where it is likely maybe there could be life forms or, or signatures of life forms, what else is the Perseverance project doing?

JOHNSON: So it's, it's sending the helicopters, that's one big part of it a technology demonstration. It's also doing some in-situ science as we explore the surface. And you've got to keep in mind, we've only touched down on a few spots on Mars, we just know so very little about what it's like to be on the surface. And so Perseverance is going to be exploring Jezero Crater trying to understand how it formed, what is its geologic history, what clues can be gleaned from that about the climate history of Mars, which is another big mystery for the Mars Science community. And it should be noted that the samples that will be returned to Earth will be studied from an astrobiological perspective, but they also may give us huge insights into the geochronology of Mars, the paleomagnetism of Mars, those are probably kind of big words, but really just understanding how old are these different rocks that were collected? And, and what sort of traces of the magnetic history can we glean? What point did Mars Stop being so habitable? And what point was the atmosphere lost to space, and Mars just kind of became the cold frigid desert that it is today?

CURWOOD: By the way, there were two other Mars missions happening around this launch. I'm thinking of the one from the United Arab Emirates called the Hope Orbiter. And there's one from China called what the Tianwen-1, what are some updates from those expeditions?

JOHNSON: It's been a banner month for Mars. You know, those two missions also arrived without a hitch. They went into orbit on February 9 and February 10. And it's just been terrific. They're starting to send back their own data. That Chinese mission is not just an orbiter. It also contains a rover and a lander. And so these other parts of the mission aren't going to get deployed right away. It's probably going to be May or June, before the Chinese orbiter has mapped enough of the terrain, figured out exactly where they want to land and put the, puts the lander down, and then the rover will come out and start exploring the surface of Mars.

Perseverance is collecting samples of Mars to be studied by astrobiologists like Sarah Stewart Johnson, seen here in green and white. These samples may contain biosignatures, or indicators of life, whether that life is modern or ancient. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Stewart Johnson)

CURWOOD: To what extent is there hope in the interplanetary community, that China and the US can work together on these expeditions?

JOHNSON: I think there's a lot of hope, I'm not sure how it will happen. I think that the scientists are really longing to have more collaboration with the Chinese. From a scientific perspective, all of the data is good data. And it's all exciting to look at, and the Chinese are going to be exploring an entirely new part of Mars, the Chinese US relations have been challenging, I'd say, especially on the political level, but maybe we'll see some thawing in the months and years to come. We see a really different dynamic with the UAE, like that mission, you know, parts of it were built in the United States, there was so much back and forth between the engineers. And so I just am very hopeful that, you know, you could have a slightly more collaborative relationship going forward. And I think that my Chinese counterparts feel the same way.

CURWOOD: So, one of the bits of technology that came to light, especially during the pandemic, is that we can literally email a virus from one place to the other. In other words, describe the sequence and then somebody at the other end can replicate it. What equipment, if any, does the Perseverance have to take a bunch of observations that then could be sent back electronically to Earth so that we could duplicate the substances or configurations that it's discovered?

JOHNSON: That's an interesting question. So all of the data is coming back to earth through these orbital relays, there are these four different orbiters that are collecting data from Perseverance and then sending it back and a big data dump. But you know, this data is caught in these giant dishes here on Earth, and relayed to JPL into the science team, which is operating remotely. One thing that we have learned a great deal about are things like what is the particular mineralogy on Mars, or what are the, you know, weather conditions and, and some of that has fueled something I'm part of, which is called a planetary analog research. And whereas we're not always creating the same thing in the lab, like we do find places on earth with relevant similarities to Mars, and we can go do work in those environments, you know, we can learn how to look for life in those types of mineral constituents and see what works best. And so that's been great. The sample analysis at Mars, which is an instrument team that I'm working on with the Curiosity rover, there was what we have been calling the Cumberland analog, where we knew the precise mineral composition of a particular sample, that Curiosity collected and analyzed, and that was refashioned in the lab, you know, a little bit of this mineral, a little bit of this mineral, a little touch of this mineral, like an old recipe. And that Cumberland analog sample is sent off to many, many collaborators and different labs to run experiments, you know, to try to dope it with certain types of organic molecules and see if you could recover them all. All kinds of things.

CURWOOD: So Sarah, before you go, give us the big picture here. What What does this mission that Perseverance is in this first wave of, and for that matter, space exploration in general, what does it mean for humans here on earth?

Sarah Stewart Johnson is an astrobiologist and a Georgetown University Associate Professor who has worked with the NASA Science Teams for the Opportunity, Spirit, and Curiosity rovers. (Photo: Brittany Waddell)

JOHNSON: Well, I think it means different things to different people. But I can tell you what it means to me, at least you know, it, it may be a while, of course, before we get these samples back, and it's by no means guaranteed that we're gonna find what it is we're looking for. But this type of exploration, I feel like it's allowing us to ask fundamental questions about our place in the universe, you know, trying to really get at this idea of, are we alone? You know, why is there something and not nothing? And did that something from nothing, did it happen once or did it happen time and again, and I just think that the science involved there is just so compelling and so interesting, but especially right now, kind of in our current circumstances, I think there's another dimension here too, which is why exploration just kind of on its own is valuable. I think it'd be really hard not to like watch this feat of human ingenuity to watch that incredible landing to think about this idea that there's this machine that was built with human hands and we've sent it off to another world. I just, I feel like that really instills the sense of awe and an inspiration and, and I guess at times like these, it just can't be a bad thing to be reminded of what a civilization can do when we're working at our very best.

CURWOOD: Sarah Stewart Johnson is an associate professor at Georgetown University, and author of The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

JOHNSON: Oh, always a pleasure, Steve. Thanks again.

Related links:

- Click here for more on NASA’s Mars 2020 mission, including the Perseverance rover

- More on Sarah Stewart Johnson’s Biosignatures Lab

- The Laboratory for Agnostic Biosignatures

- Sarah Stewart Johnson on Twitter

- Click here to listen to LOE’s previous interview with Sarah Stewart Johnson on The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World

[MUSIC: U2’s “Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For” on The Joshua Tree (Super Deluxe), Island Record]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. We bid farewell to intern Leah Jablo. You are missed. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth