July 21, 2017

Air Date: July 21, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Steep Wildlife Decline

View the page for this story

A Living Planet report from the World Wildlife Fund based on 2016 data documents nearly a 60% decline in wildlife populations since the 1970’s and warns that two thirds could be gone by the year 2020. Living On Earth Host Steve Curwood discussed the implications with WWF scientist Colby Loucks. ()

Saving East Coast Sea Life

View the page for this story

President Obama designated nearly 5000 square miles of canyons and deep ravines in the seas off Massachusetts the first marine national monument in the Atlantic. Speaking with Host Steve Curwood, New England Aquarium Scientist Scott Kraus describes this maritime treasure’s extraordinarily rich biological diversity, from massive corals to single-celled organisms the size of softballs. ()

Science Note: Rats Against Poachers

/ Aidan ConnellyView the page for this story

African pouched rats can grow to a yard long, and have a very acute sense of smell. So the US Fish and Wildlife Service is devoting research funds to study whether they can sniff out trafficked animal products and timber. ()

DNA Tech for Rhino Protection

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

With rhinos on the verge of extinction, conservationists are turning to novel efforts to prevent poaching. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on how a DNA database in South Africa is helping law enforcement agents identify the origins of seized rhino horn in order to deter poaching. ()

How to Save Most Species: Part 1

View the page for this story

Within decades Earth may lose as many as 50% of the species currently living on our planet. To avert ecological disaster, renowned conservationist and Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson has proposed a radical idea in his book Half-Earth: to set aside half of Earth’s land and sea for nature. He believes that this could save 80% of the species and preserve ecosystems. Host Steve Curwood spoke with E.O. Wilson to learn why the 87-year-old ecologist is optimistic about the role of technology to help with this mission. ()

How to Save Most Species: Part 2

View the page for this story

Within decades Earth may lose as many as 50% of the species currently living on our planet. To avert ecological disaster, renowned conservationist and Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson has proposed a radical idea in his book Half-Earth: to set aside half of Earth’s land and sea for nature. He believes that this could save 80% of the species and preserve ecosystems. Host Steve Curwood spoke with E.O. Wilson to learn why the 87-year-old ecologist is optimistic about the role of technology to help with this mission. ()

BirdNote: The Stealthy Shoebill

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Deep in the swamps of central Africa lives one of the strangest looking of birds; the Shoebill Stork. The name comes from its huge broad sharp beak, and only about 8000 of these large grey-blue birds survive. As Mary McCann explains, it’s actually related to the pelican, rather than storks. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Colby Loucks, Scott Krauss, E. O. Wilson

REPORTERS: Aidan Connelly, Bobby Bascomb, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The first Marine National Monument in the Atlantic features

deep canyons and mountains with extraordinary biodiversity of sea-life.

KRAUS: There’s a coral called Bubblegum coral and it looks like someone just kept sticking bubblegum together until you had a very large coral piece. These things grow 8-10 feet tall, and they live over 1000 years, it’s like an underwater Joshua Tree.

CURWOOD: Also – there are only 25,000 rhinos left in the world – and they are falling fast to illegal hunting. Now DNA science is giving them a fighting chance.

SOEKOE: We’ve had two rhinos poached on our concession this year, both of them right behind us over here, where the poachings took place right next to each other. The one was successful, they did get the horn, and the other one we kind of distracted them a bit earlier, so they weren’t successful in getting the horn, but unfortunately killing the rhino.

CURWOOD: Those stories and biologist E. O. Wilson, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Steep Wildlife Decline

The index states that freshwater species will bear the brunt of forces that reduce population globally. (Photo: Cloudtail the Snow Leopard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

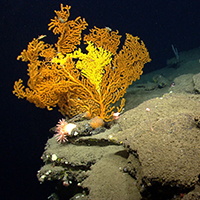

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London release a Living Planet report every two years or so that assesses how the natural world is coping with the stress of rising human population. It is a grim trend. This year they report global wildlife populations have already declined by almost 60 percent since the 1970s, and the losses continue. Colby Loucks is the senior director of the Wildlife Conservation Program for WWF, and he joins us now to explain. Welcome to Living on Earth.

LOUCKS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, in brief, tell me what are the findings of this Living Planet report?

LOUCKS: The big findings are that we've seen a 58 percent overall decline in the population sizes from 1970 to 2012. So, what that is, is if in 1970 you looked out your window and saw 100 of your favorite species out your window, today you would only see about 42. So, in a single population there's a 58 percent decline, but that's averaged across over 3,700 vertebrate species.

CURWOOD: So, in other words I look outside the window now where I used to see 100 crows and they’re noisy, and now I'm just seeing 42. And then in my pond where there used to be 100 frogs, now there are way less than 42.

LOUCKS: Yes, that's a good point, and the freshwater loss is tremendous, and so in your pond if you saw 100 frogs, now you might only see 19.

CURWOOD: Wow. So what was the data your analysts used to put this report together?

LOUCKS: Well, most of the data comes from published scientific literature. There's many many researchers around the world and research organizations that are monitoring their own individual populations, so it's basically collecting all that information and putting it into the analysis.

CURWOOD: What are the factors that are driving these rapid losses in wildlife?

The Living Planet Index charts a steep decline in biodiversity in the late half of the 20th Century. (Photo: World Wildlife Fund)

LOUCKS: Well, the overall, major, number-one driver is just the habitat loss. In the simplest terms you could think of a forest being converted to a farm. Also, for a lot of the wildlife, the number-two driver of loss is overexploitation, which is fancy word for saying, just taking too many out of them. So, on the terrestrial side of things, that is going to be poaching. In the marine areas, it's usually overfishing. And then, if you add maybe three more of the big drivers, it’s going to be pollution, especially bad for freshwater, and then invasive species and then finally climate change. So, there's sort of like the five Horsemen of the Apocalypse for populations that are in decline.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what species are crashing the fastest?

LOUCKS: The biggest loss of wildlife is certainly going to be in the fresh water. So, the fresh water species have lost, on average, 81 percent of their size between 1970 and 2012 so they are driving a lot of the loss. And you can imagine fresh water, 0.8 percent of our land surface is fresh water, but we need it for so many things. We need it for drinking water, we need it for agriculture, we use it to create dams to generate hydroelectricity, and all of that affects the fresh water biodiversity. So, we have a lot of these river dolphins -- these big dolphins that are in rivers that need a lot of space, need a lot of fish, need to migrate and they're really affected by the pollution, the destruction of the rivers, and so I would say the fresh water biodiversity is really taking it on the chin.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the regions of the world that you think will most likely have the biggest species loss.

LOUCKS: Well, it's interesting. Historically a lot of the species loss may have come from the areas of the temperate zones, so North America, Europe and Russia, where there's just a lot more people over hundreds of years, thousands of years. And so that's certainly in place, but that's also the regions where we've started seeing some rebounds in some of the wild cats that are in parts of Europe. On one hand, we have that kind of a dynamic going on. On the other hand, you have a lot of the tropical areas that are being converted from forest, tropical forest, to agriculture, or some of those rivers are finding new dams. So, those are probably the areas where we're going to see increases in declines. Also the tropics just have more species in them than the temperate forests.

CURWOOD: So, at this rate of decline ... You know, I'm trying to do some math here … How wrong am I? It looks like this research would indicate we would just be out of wildlife by the middle of the century.

LOUCKS: Population sizes are getting smaller, but they're not necessarily going extinct locally. So, the fancy word for that is "extirpated.” So, there's still going to be wildlife, but what there are, you're just seeing smaller numbers of those same populations, but the populations will still be there.

CURWOOD: So some has been critical of the metrics of your study, say it oversimplifies a very complex problem. From your perspective where does the value and the merit of this report’s data lie?

Colby Loucks directs the Wildlife Conservation program at the World Wildlife Fund. (Photo: Colby Loucks)

LOUCKS: It is a challenge. So, what we have is a single number, 58 percent decline in populations, and so the challenge is to try to portray this information that can be digestible, and I think it's not too different from other major numbers that we hear about such as gross domestic product, right? So the GDP ... GDP is the economic output of a country, and most people can understand that ranges from Apple to your local florist in the basement of our building here. They're very different, but they also have this economic output. Same with the Living Planet Index. So, we have elephants in Kenya to salamanders in West Virginia, and so it's trying to capture and give you a taste in the sense of what is happening.

CURWOOD: Colby, you sound all very calm telling us this story, but it sounds pretty scary to me.

LOUCKS: [LAUGHS] Yeah, you have to have a bit of optimism in this field and you have to take a lot of negative news, but you have to find the positive places where you can succeed, and, yeah, there's a lot of areas for improvement individually to governments.

CURWOOD: Colby Loucks is the Director of the Wildlife Conservation Program for the World Wildlife Fund. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Colby.

LOUCKS: Thank you. It's been an absolute pleasure.

Related links:

- The 2016 Living Planet Report

- Bushmeat hunting a major driver in biodiversity decline

- Colby Loucks profile

Saving East Coast Sea Life

A peek at what lies below the surface less than 150 miles of the New England coast, where President Obama recently designated the Atlantic’s first National Marine Monument. (Photo: Green Fire Productions, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

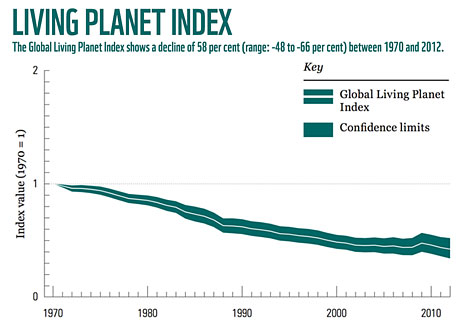

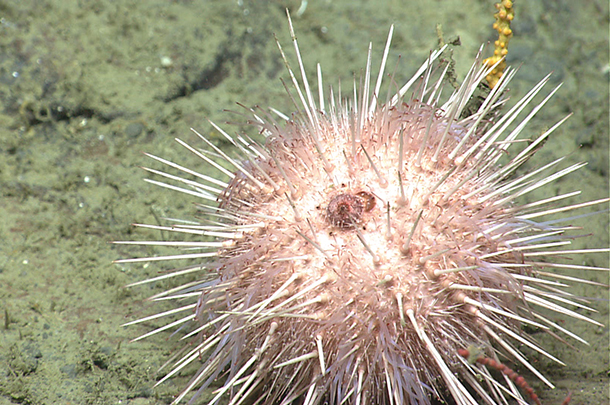

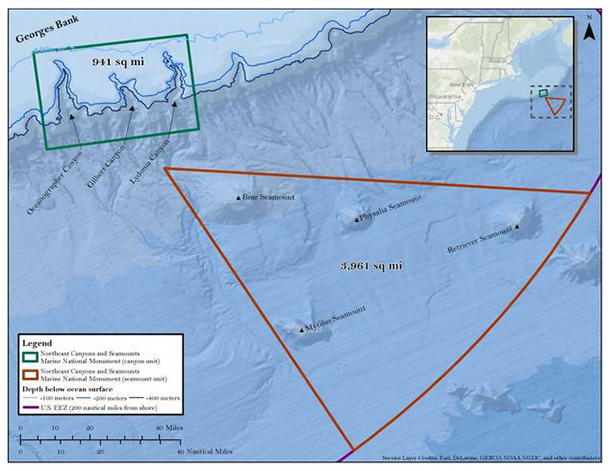

CURWOOD: Any day now, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke may send the White House his review of the National Monuments the president ordered him to consider for potential resizing, rescinding or modification. Some 27 monuments are on the list including the first national marine monument in the Atlantic Ocean, at the edge of the famous fishing grounds of Georges Bank created by President Obama in October 2016. There are canyons deeper than the Grand Canyon and four large underwater mountains in nearly 5000 square miles of ocean, that now has the same status as a national park. With a rich biodiversity that includes massive corals, New England Aquarium senior scientist Scott Kraus calls this area 130 miles off Cape Cod the Serengeti of the Seas. He joined us when the Monument was declared and described what it was like.

KRAUS: The Monument’s area is the edge of the continental shelf of the United States. So the water drops from the top of Georges Bank. It's perhaps 300, 400 meters deep, and all of a sudden, it drops off to four miles deep, and in that steep drop-off there are underwater canyons created, you know, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousand years ago, and then in addition to that it also ... Georges Bank sticks out into the Atlantic so you have these deepwater currents coming up out of the Gulf Stream and elsewhere that rush up and bring a lot of nutrients out of the ocean floor to the surface. So, the place is remarkably productive.

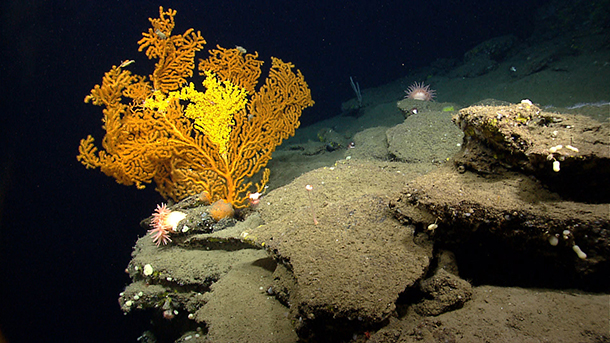

A sea urchin found along the Southeastern wall of Oceanographer Canyon, one of the three included in the monument. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what do you see? What kinds of creatures and what do you see in those canyons and around all those underwater mountains?

KRAUS: In terms of the number of species that occurred there, and the number of animals it's significantly higher than all the surrounding areas. I guess the way I would explain it is, you can see thousands and thousands of dolphins and Pilot whales and Sperm whales extending along the shelf edge for miles and miles, and I have seen thousands at a time. The thing that it reminds me of is that those kind of National Geographic images of the great migrations on the African plains like the Wildebeest migrations and so on. It's just thousands of animals. And the only difference is that there's more diversity in some of these habitats. The Monument’s area has got, oh, probably eight different species of dolphins, several different species of Pilot whales and grampus, and then sperm whales and a lot of Beaked whales, stuff that you don't see in coastal waters at all. It's not your average whale watch.

CURWOOD: If you were to give me a short list, which species will be positively impacted by this new protected status of this marine territory?

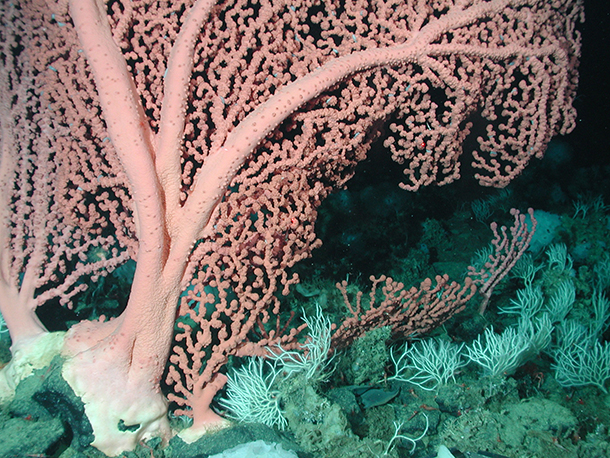

KRAUS: Probably the deep-sea corals. Deep-sea corals are easily damaged by trawlers, or even traps setting on them can damage them. We've seen some evidence of that in the deep-sea dives that have been done out there. So there's an incredible diversity and abundance of corals in this monuments area down in the canyons that are just beyond imagining. So, for example, there's a coral called Bubblegum coral and it looks like somebody just kept sticking bubblegum together until you had a very large coral piece. These things grow eight to 10 feet tall and they live over 1,000 years. It's like an underwater Joshua Tree, you know, these animals live for an extremely long time, but therefore they're quite fragile, you don't want to disturb them or break them cause they been around a lot longer than we have and it'll take them a long time to get back.

CURWOOD: So let me ask you, specifically, what types of human activities does this designation as a National Marine Monument prohibit then?

The monument includes four underwater seamounts and three underwater canyons, located along the Georges Bank. (Photo: The Pew Charitable Trusts)

KRAUS: It will prohibit all fishing. There's a phase out period for red crab and lobster over the next seven years, and then all commercial fishing will be banned. Recreational fishing is allowed. It eliminates all possible oil drilling. The mining issues will be put to bed as well. There will be no deep-sea mining, so it's really protection from major industrial activities.

CURWOOD: Now, opponents of this Monument say it will have devastating impacts on New England's fishing industry. Your thoughts?

KRAUS: There are some fishermen who fish out there. I don't think there are any fishermen who fish out there year-round. Most of them are limited to a couple of seasons, and the data that I've seen on fishing activity out there indicates a very small number of people working there and a very small percentage of their time is spent there. So my suspicion is that this is not a big economic problem. I've heard wildly exaggerated numbers about thousands of fishermen and millions of dollars and the data just doesn't support that.

CURWOOD: How important is this area for helping breeding populations of fish up there on the continental shelf?

KRAUS: For this particular area we don't know that. Those kind of studies haven't been done, but the other thing it does that’s really important is that we live in a world where the oceans are warming fairly rapidly and they are becoming more acidic. The climatological changes in the north Atlantic are, and in fact in the Gulf of Maine, are happening faster than anywhere else in the North Atlantic, and so we really need reference habitats that are not disturbed by all kinds of human activities, and this is a really good one for that.

“Bubblegum Coral,” an organism found in the new monument. (NOAA Photo Library, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So there was an earlier version of this proposed monument that covered an even wider part of the ocean. How convinced are you that the final plan adequately protects and preserves these important habitats in the Atlantic?

KRAUS: You know, if you're a marine mammal, more is better. If you were a fisherman, you would say less is better. But bigger would have been better from a scientific point of view only because you would capture more of the diversity in that area. In the long term, I think it's too early to tell, but I think the advantage of this is that it puts a stake in the ground that allows us to start thinking about what a marine protected area might do, both for fisheries and for understanding climate change and understanding the ecosystems. This is an area that is not well studied. There's a lot more to do. There's big areas where we haven't had a look around. There's species being discovered there every time somebody goes down. I'm a marine mammal guy so I like whales, right? But my favorite animal in this monument is something called a Xenophyophore for, which is the largest single-celled animal in the world and they roll around in the sand and the bottom and they get sand on the outside. I don't know what they're thinking, but it's really impressive to have a cell the size of a softball.

Scott Kraus is a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Scott Kraus)

CURWOOD: It's the size of a softball?

KRAUS: [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: That's a big cell!

KRAUS: That's a big cell.

CURWOOD: So, how do you think this Monument is going to affect the way that we as a nation possibly think about the oceans, and about how we proceed with ocean conservation at the national level?

KRAUS: These conversations are going to go on for a long time. I think that climate change is going to force the discussion into places that nobody expects, that there are going to be changes in commercial fisheries, there are going to be changes in sea level and coastal resilience that are going to make people think much more carefully about preservation, certainly of ecosystems. I mean, we've learned our lesson from, I would say, Katrina. If you look at the way in which we altered the coastal ecosystem outside of New Orleans, people are now realizing, oh my god, we've got to put back mangroves, we've got to get rid of these canals, we've got to do things that actually are more in keeping with the original shock absorbers that Mother Nature provided, and I suspect that we're going to see that kind of discussion take place around marine national protected areas all around the country.

CURWOOD: Scott Kraus is a Senior Scientist at the New England Aquarium and Research Professor at University of Massachusetts, Boston. Thanks much for taking the time today, Professor Kraus.

KRAUS: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Scott Kraus’s presentation and original research text assessing the then-proposed marine monument

- NOAA: What is a marine national monument?

- The President spoke about the monument at the Our Ocean Conference

- Obama also expanded the Papahanaumokuakea monument this year

- Press release from anti-monument organization Saving Seafood

- Scott Kraus UMass, Boston Faculty Profile

Science Note: Rats Against Poachers

A landmine-detecting rat enjoys the spoils of labor (Photo: Gooutside, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Coming up -- how rhino DNA could help save the species and fight poachers, but first this note on emerging science from Aidan Connelly.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

CONNELLY: The African pouched rat isn’t quite like the rodents you see scurrying along subway tracks, or hanging around your local dumpster. These rats are nearly three feet long– including their 18-inch tails. And their size, along with their acute sense of smell, makes them almost more like dogs.

It’s because of that sense of smell that the US Fish and Wildlife Service has pledged one hundred thousand dollars into studying these rats, in hopes of using them to sniff out timber and wildlife trafficking in Tanzania.

An African Pouched Rat in Florida, with human for scale. (Photos: FWS, Wikimedia CC BY 2.0)

Tanzania already has a history of using African pouched rats – specifically their noses – for a number of purposes. They’ve been used to diagnose tuberculosis, as well as to detect landmines, where they’re suited up with harnesses, and fed bananas when they do a good job. Now, these oversized rats are on a new mission: Searching out wildlife crime, specifically trafficked Pangolins, the most widely poached animals in the world.

The Research funds from US Fish and Wildlife will help test the rat’s effectiveness, and, if experiments work, will help set up a program to deploy them directly to the front line, at Tanzania’s ports. If they prove effective, the African pouched rats could become invaluable to anti-trafficking groups not just in Tanzania, but around the world.

And that could be promising news for everybody: Humans, pangolins, and the three-pound, banana-munching rats themselves.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Aidan Connelly.

Related links:

- NYTimes Op-Ed Columnist Nicholas Kristof: “The Giant Rats That Save Lives”

- The USFWS plan to combat Pangolin trafficking with African pouched rats

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

DNA Tech for Rhino Protection

White rhino. (Photo: gmacfadyen, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some of the most threatened animals on the planet live in Africa, and none face more dire threats than rhinos. It seems a rhinoceros is killed every day or so, as poachers go after their horns, which are lucrative commodities in the Asian traditional medicine trade. With just 25,000 or so rhinos left in in the world, the threat of extinction looms large. But now an international database that keeps track of 75 percent of them is offering some hope. This database is housed in South Africa, and from Pretoria, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on what it does, and how it may help save this iconic animal.

[TRUCK DRIVING]

Amy Clark, a laboratory technician at the Veterinary Genetics Lab at the University of Pretoria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Brittle yellow grass gently blows in the wind at the black rhino game reserve near Pilanesburg National Park in South Africa. Mathew Soekoe is a field guide here. Driving a safari truck he scans the familiar landscape and points towards a nearby fence.

SOEKOE: We’ve had two rhinos poached on our concession this year, both of them right behind us over here, where the poachings took place right next to each other. The one was successful, they did get the horn, and the other one, we kind of distracted them a bit earlier, so they weren’t successful in getting the horn, but unfortunately killing the rhino.

BASCOMB: Stories like that are extremely common here. So common that South African law requires that a tissue sample must be collected any time a rhino is moved from one park to another or receives medical care. The sample is used to create a DNA profile for each animal that can be recorded and, in case the animal is ever poached, can be matched to confiscated rhino horn.

[FREEZER DOOR CLOSES AND A SAMPLE BAG IS OPENED]

CLARK: What I’m going to be doing is I’m opening a routine kit from a live rhinoceros that has been collected in the field.

BASCOMB: Amy Clark is a laboratory technician at the Veterinary Genetics Lab at the University of Pretoria. She opens a plastic bag to examine small tubes holding rhino skin, hair, and blood. She pulls out a piece of paper with information about this specific rhino.

CLARK: We know from this particular animal that it is from a male white rhino. It is from Limpopo province, in South Africa. And this was from a live rhino.

[WALKING AND DOOR OPENS]

BASCOMB: Clark carries the samples down a hall to the sample preparation room where technicians pound rhino horn to a powder or cut off a small piece of tissue to examine. Then they add the samples to a solution and heat it.

CLARK: The heat causes the cells to break open and release the DNA. And from there we take that solution to a machine that uses magnetic beads to pull the DNA out of solution, so we can get a good quality DNA profile.

BASCOMB: The veterinary lab has a forensic analysis for roughly 18,000 rhinos. That’s nearly three quarters of the total population, and they hope to eventually register every rhino in the world. The rhino registry helps officials prosecute poaching crimes. Dr. Cindy Harper is the director of the lab. She says criminals in possession of illegal material like rhino horn might get a slap on the wrist, but when they’re linked back to a dead rhino -- a crime scene -- they’ll get a much harsher punishment.

HARPER: We’re looking at cases where poachers get 29 years and more because they are actually involved in an illegal hunt and not just possession of rhino horn.

A rhino tissue sample kit (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: The sentence for poaching can vary greatly depending on the country where the poacher was caught. Rhino poaching is a well-organized, highly profitable crime, run by a heavily armed international syndicate. Harper says her DNA database allows officers to keep tabs on how poachers are operating.

HARPER: If you look at it internationally that gives you some idea of the traceability of where that horn had moved from the carcass to its final destination and how quickly it moved.

BASCOMB: It’s connecting the dots like that, between crime scene, transit, and consumer, that Jorge Rios says is so critical. Rios is the chief of the global program to combat wildlife and forest crime at the UN office of drugs and crime. He says training prosecutors in the countries where rhino horns end up is the next step.

RIOS: You need to have a number of concurrent processes going. You need to do the forensics but, even if you have that information, you need to have the criminal legislation in place, and you need to have investigators and prosecutors who know how to use the scientific evidence. You need to train along the entire chain of enforcement.

BASCOMB: The ultimate source of wildlife protection, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, recently met in South Africa. Rhinos have had the highest level of CITES protection since 1977 when trade was completely prohibited. This year the Kingdom of Swaziland petitioned to legalize the sale of humanely harvested horn. CITES delegates declined to pass the new rule, fearing that illegal horn from poached animals could be laundered in with the sustainably harvested horn. But Pelham Jones from the Private Rhino Owners Association says the rhino DNA database would make that impossible.

JONES: Because every horn, before it enters the trade market, has to go through the process of verification of its DNA etc. so in simplistic terms, if you’re not a chicken farmer you cannot be bringing chicken to the market. So, can illegal horn enter the market on the South African side? We say, no, it cannot because of the traceability via DNA.

BASCOMB: DNA technology is also being used to create synthetic rhino horn. A biotech company in Seattle, Washington makes synthetic horn, which they hope to sell at a lower price than real horn and put poachers out of business. But Cindy Harper from the DNA lab says the synthetic horn is virtually indistinguishable from the real horn, so she believes it’s a bad idea.

HARPER: The company that’s currently really at the top of the drive is wanting to put DNA into synthetic horn, that is something I simply don’t understand. I don’t see any other synthetic product, such as synthetic fur or meat or anything else, having the actual animal’s DNA put into it. The only reason I can think for doing that is to make it impossible for law enforcement to differentiate that.

A lab tech processes a rhino DNA kit (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Harper says, law enforcement agents already have their work cut out for them. She estimates that just one percent of seized rhino horn samples actually come back to her lab to get matched up on the database.

HARPER: That is the next step in the process. Making sure that we get these seized samples back and to be able to look at the whole movement of these horns globally. The criminals are organized. We need to make sure that everybody else who’s fighting those criminals are equally organized.

BASCOMB: Harper’s lab is working hard to register all of Africa’s rhinos, but there’s a long way to go, and it’s a race against time. More than 1,300 have already been killed so far this year.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Pretoria, South Africa.

Related links:

- “South Africa deploys CSI-style tactics to crack rhino poaching rings”

- White rhinos are considered Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UKcGCObEb28 Hugh Masekela, “Grazing In the Grass” on Hope, Columbia Records]

How to Save Most Species: Part 1

Above, a wildlife bridge helps critters safely cross the Trans-Canada Highway near Banff, so that their habitats are connected. E.O. Wilson calls for an extensive, connected network of ecosystems to be reserved for nature in North America – he calls it, “Squaring America.” (Photo: WikiPedant, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

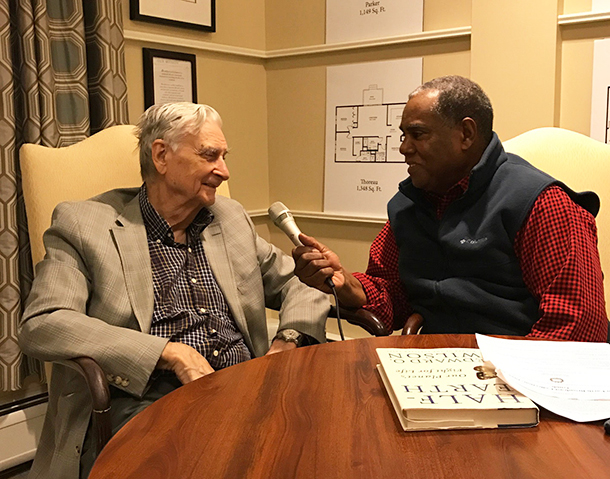

CURWOOD: A bold new proposal to stem global species’ loss has been created by one of the world’s top experts in ants.

WILSON: Edward, middle initial “O” Wilson, honorary curator of insects at the museum at Harvard.

CURWOOD: E. O. Wilson, as he’s commonly known, has won two Pulitzer prizes, including one for his book on ants. But the distinguished Harvard biologist has been studying the challenge of species loss for years, focusing on unique habitats that should be conserved to protect the diverse ecological webs within them.

Now in his book "Half-Earth", he has done the math. He says we can preserve the bulk of species and ecosystems if we set aside half of the Earth’s surface, both land and sea. I spoke with Professor Wilson at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts, and he explained why many ideas for how to tend to Nature are, well, misguided.

WILSON: I’m concerned because those that I like to call the “Anthropocenists,” that is, those who feel humanity has so thoroughly changed the surface of the Earth and the seas as well, that we might as well give up. The Anthropocene, carried to an extreme in its conception is that we've lost the battle in terms of saving natural areas, even in terms of saving most of the biodiversity, the variety of life left on Earth, so we should follow along now in the next stage either one, to just let it go, and proceed to humanize the entire globe. Maybe that was the destiny of the planet. The second version of Anthropocene enthusiasm is, “Don't worry, the species that have gone extinct, if we keep specimens of them, we'll keep their DNA, and we'll find out a way to clone them, and we'll put them all back eventually and recreate natural ecosystems.” All these and similar schemes that have been suggested, relatively the same in my view, as running up the white flag as soon as you see the pennants of the enemy appearing on the horizon.

CURWOOD: So we can do better, you think.

WILSON: We better do better! [LAUGHS] Yes, we can do vastly better, and the conservation movement around the world has been doing everything possible in a conventional worldview with nobility of purpose, with enormous energy and effort and dedication. It's saved a lot of species.

E.O. Wilson’s latest book is Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. (Photo: W.W. Norton)

But what most people don't realize is that in addition to those beautiful big animals that we so admire and we see going extinct or up to the brink of extinction, there are literally millions of smaller creatures that are the foundations of our ecosystem both on the land and the sea, and that they, too, are probably disappearing at about the same rate. So that we simply are not doing enough for the vertebrates.

That's the group we know the best because we know all of these vertebrates. We know the fish, we know the amphibians, and we know the birds and mammals and reptiles. One-fifth of those vertebrate animals I just listed are sliding down at a pretty rapid rate and going off the cliff to extinction, and of that one-fifth we're losing, even with our best efforts, 80 percent or so. We haven't stopped it. We've slowed it, but we haven't stopped it. So, we needed something completely different.

CURWOOD: And the bottom line? Of course, we're talking about your book "Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life."

WILSON: Yes, the book's premise is that what we need to do is try for a moonshot, and the moonshot is to set aside half the surface of the land and half the surface of the sea as a reserve, a reserve that doesn't exclude people by any means -- indigenous people are, in fact, encouraged to enjoy them and continue their way of life -- but, if we could give half of the Earth primarily to the millions of other species that inhabit the Earth with us, then we would be able to save about 80 to 90 percent of the species, bring the extinction level down to what it was before the coming of humanity. That would be a successful moonshot.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me with some math about the concept of Half-Earth. Just how could this work? How would this work?

WILSON: So, where are we right now? And I can tell you that, in the United States, we have already put aside about 15 percent of the land surface, and, for the planet as a whole, this is land. We're about the same. We are at about the15 percent mark around the world for the land. And for the sea it is far less, somewhere about one to three percent, and in the United States it’s up towards what it is for the land. It's about 10 percent of the territorial waters of the United States. So, we need to move that on up to about half in order to reach a fairly safe level.

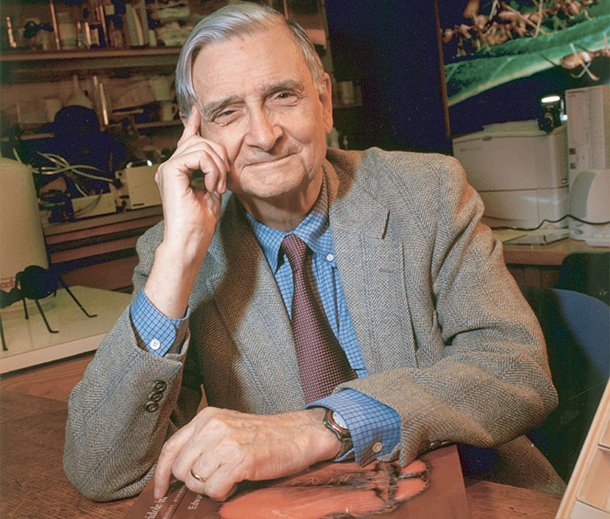

Host Steve Curwood interviews E.O. Wilson at the ecologist’s home in Lexington, MA. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

Can we do it? Yes, we can do it. Just taking opportunities, gerrymandering small pieces, linking existing parks and small reserves together, we can move the United States up to 50 percent.

CURWOOD: That’s biologist and conservationist E. O. Wilson.

Related links:

- E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

- Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life

- About E. O. Wilson

[MUSIC: Tim Gartland, “When the Next Wind Blows” on Million Stars, Taste Good Music]

How to Save Most Species: Part 2

Above, a wildlife bridge helps critters safely cross the Trans-Canada Highway near Banff, so that their habitats are connected. E.O. Wilson calls for an extensive, connected network of ecosystems to be reserved for nature in North America – he calls it, “Squaring America.” (Photo: WikiPedant, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: We’re back now with renowned conservationist E. O. Wilson, whose recent book "Half-Earth" proposes a daring idea. He says we need to set aside half of the Earth’s land and sea for the 10 million other known species on the planet. To reach that ambitious goal, Professor Wilson imagined how we might conserve so much North American land.

WILSON: I have a notion I call "squaring America”, North America, including the United States. We start Yukon to Yellowstone. That can be done right now, but let's go on. Yellowstone on down to the Rocky Mountains, and we could easily -- well relatively easily -- set up reserves all the way down there as a continuation of the corridor. We get to the southern Rockies, and then we have to jump over a bit to the Sky Island Mountains of Arizona. If we wanted, then we can continue the corridor -- if our Mexican neighbors would like it -- in the Sierra Madre Occidental. And we now go back up to the Yukon, and let us think of a great, broad corridor across the coniferous forest the height of Canada.

Then, reaching the Atlantic coast, let's bring it down through the best-forested areas to Maine and over to the still wild areas of Vermont, New Hampshire, through surprisingly open areas that remain in upstate New York until we arrive at the Adirondacks. Now, we continue the square down onto the southern Appalachians which reaches then to northern Georgia and Alabama.

But now comes the Gulf Coast. We would like to see a corridor from at least as far east as Tallahassee, extending along the Gulf Coast, which is biologically the richest part of North America, incidentally, in numbers of species. It extends on over to Louisiana and Eastern Texas.

E.O. Wilson says his “moonshot” idea to conserve half of the land and half of the sea for nature is the best shot we’ve got at saving 80% of the species now living on Earth. (Photo: Louis Raphael, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

That then, if you think about it, would box America, north, south, east, west, on our square. By the time you pull that off, if you can, you've really added a large amount of natural area.

CURWOOD: So, what is it about us humans that a majority of people don't share your view, don't understand your urgency, your sense of urgency about this? What is it about us as a species that you think gets in the way? And you write about this some in your book "Half-Earth.”

WILSON: I'm afraid that's part of what we call human nature. I believe the reasons why we do so many stupid things, including having constant war and tribal battles and internecine civic strife and conflict between religious faith, we succeeded as a species. You know, we were just one species out of many creatures that look a little like us, anyway, the Australopithecus and pre-human species. There were quite a few that came into existence and died off, and our stock was the one that got hold of the capacities for language and dividing labors of cooperating groups. We were the one species that got out from Africa, and we did it about 65,000 years ago, and our populations, our ancestral populations everywhere as they spread, and of course as they multiplied in Africa itself, they would enter whole new environments, natural environments, and everywhere they went they met the pristine environments and they found survival by utilizing everything they could get their hands on in that pristine environment.

They began by killing off, in many cases, the native birds and mammals for food. They then cleaned out a lot of the environment with the plant environment by harvesting. They began to develop agriculture -- That began about 12,000 years ago -- and that meant just spoiling the original environment. We survived. We multiplied. We were Darwinian. Those among us who did the most damage to the environment to our benefit were the ones who typically got ahead of the competitors in the next area over, and surely that has had an effect on the evolution of human rapaciousness when it comes to dealing with environment. That's why it makes it so hard to say, “Please halt and reconsider before you mow down that rainforest. Please consider leaving enough space on the surface of the Earth and the sea for those estimated 10 million other species that exist, and which we are wiping out at a rapid rate.” We don't know what we're doing, and we're destroying something ineffably beautiful and something the human mind and emotions need. Because we still have a deep love of the natural environment which we evolved and that included the richness of life and the beauty of open unspoiled areas.

Most ecosystems on Earth have been impacted by non-native species that humans have either inadvertently or intentionally transplanted. The paperbark tree (Melaleuca quinquenervia) is native to Australia but is now present on all main Hawaiian Islands and the mainland U.S. (Photo: Rose Braverman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Why do humans need other creatures? I mean, to what extent are they just nice for us to see or how vital are they for our survival?

WILSON: When you start reducing ecosystems by allowing species to go to extinction, then what you were doing is weakening the system as a whole, and then it becomes vulnerable to accelerating change and collapse. We're worried now with good reason about climate change and the fact that we are racing toward almost lethal conditions for life as a whole if we continue on our present path, but what's less recognized is that the same thing exists for biodiversity, and the variety of life that make up the natural ecosystems in the world. We're moving toward a point where the whole thing could begin to unravel with disastrous results for people locally and globally.

CURWOOD: So, some folks would say, “Look, why not novel ecosystems, those that gradually emerge when alien species invade natural ecosystems? They might be good enough.”

WILSON: Oh, you say that so convincingly. [LAUGHS] I know you're posing the question. Well, we were talking earlier about the Anthropocene, and I told you the stunning fallacies they engage in. This is the next one. They said, “Well, all around the world, humans around the world are carrying, whether they intend to or not, these alien species, and they’re releasing them, and these are in the worst most disturbed areas that sort of building up little ecosystems of their own. These are highly unstable, and they also include some of the worst pests for humans, and of course they’re very bad for the native species that come in contact with. Novel ecosystems are something to resist and not think of ever as a substitute for a far richer and more stable natural environment. If you want an example of a serious novel ecosystem, go to Hawaii. When you get off the plane, when you get your lei around your neck, you will probably not have a single native plant species in there. There will be species of plants -- some of them beautiful -- that have taken hold in Hawaii and that can be seen at almost any port of call around the tropical world. The birds you see are all going to be introduced birds. So, what you're seeing, then, is a hodgepodge of alien species from all around, and we don't want that to be the condition of the world.

CURWOOD: So, one of the things you're write about this book is having a Lord God moment as a naturalist. Tell me what you mean by that, and your favorite Lord God moment.

The distinctive, now-extinct ivory-billed woodpecker, origin of the phrase “Lord God Bird”. (Photo: satragon, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

WILSON: OK. Well, the Lord God moment comes from the southern name for Lord God bird. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker never was very abundant, so that southerners, settling across the south, would occasionally see one. And when they first saw one -- the second-biggest woodpecker in the world, you know, brilliantly colored -- well, when they first saw the birds, people often said something like, "Lord, God, what is that?" And that spread enough so that many of them called it a Lord God bird.

And what can I say? I have had many Lord God moments, but mostly with ants. One such moment was in the tropical forest when I first saw a swarm of army ants, up to millions in one colony marching as a broad front like a conquering army spreading through the forest floor capturing everything it could find and kill for their food and then settling back into a heavily guarded bivouac where they live. That should be a Lord God moment for anybody to see that.

CURWOOD: Of course, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is gone. You can't find it any more.

WILSON: It's gone. And the last one was seen, I think, in the early 1940s by a little boy who knew where a single Ivory-Billed Woodpecker would rest for a while, and he would go out to see it, and then one day that was gone, and all hunts for it have failed. I would have given anything to be able to see an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker.

CURWOOD: You have a name for the geologic epoch we may be creating here if we continue on the path of destroying habitat and causing species extinction. What is this name and tell me why you call it that?

WILSON: Well, you know, about the time of the name Anthropocene, the Age of Man, came in, I suggested that we use the term for this period that we dominate the world as the Eremozoic. Eremo means lonely. So Eremozoic means the Age of Loneliness. And for me, kind of the saddest part of all, there would be a heavy weight on the human soul if we really entered it, would be the Eremozoic, the Age of Loneliness where most of life on Earth that we evolved in, most that you and I are still living in, was gone forever.

E.O. Wilson in his office at Harvard surrounded by images of the ants he studies as a myrmecologist. (Photo: Jim Harrison, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.5)

CURWOOD: And maybe our planet, our species, shouldn't try doing without the other species, huh?

WILSON: I think we shouldn't try that. We only have one – I like to call it, “One Earth, one experiment.” We've only got one shot at this. Let's be careful.

CURWOOD: I know that you're especially optimistic about the role that technology could play in conserving biological diversity? Why do you think the digital revolution is going to help nature rather than make things worse?

WILSON: You know, the first reaction to thinking about digital civilization we're moving into so dramatically right now is going to be bad for the natural environment. That's because we think about the digital revolution in the same terms that actually did exist leading up to it, but the digital revolution has qualities to it that are not shared, by any means, with the first primitive technological industrial revolution, and those qualities all point to a lessened size of what's called the ecological footprint. And everyone, I think, should know what the ecological footprint is because it's critical.

Ecological footprint is the amount of area – of space if you wish to make it three-dimensional -- required by the average person to maintain for that one person all of the necessities of life. That ranges from food to water to shelter to entertainment to governance and on and on and on. And for most of the world it's one to 10 acres depending on the country. For America, it's much higher than anybody else, and it's not sustainable.

And why would I be optimistic that the digital world is going to shrink that? That is the nature of economic evolution, that people want and they will select if they have any choice, instruments and material goods that are smaller, consume less energy and material, need to be fixed less frequently and all of that means that the ecological footprint is destined to shrink. If we can now keep our hands off of the natural areas in the world, if we can devise entertainment and fulfillment making use of all of the accouterments and monuments of digital age and develop a conservation ethic, I envision a possible paradise for humanity by the 22nd century.

CURWOOD: Paradise for humanity by the 22nd century, and right now we're threatened by climate change, pollution, and loss of species at a precipitate rate?

WILSON: Well, I know. But now let's think about the United States over a comparable period. The development of the nation as a society from, say, 1800 to 1900, humans are making that rate of change, and I believe there's an inevitability of the shrinking of the ecological footprint, not because people know what it is and want to see it shrink, but because of the economic evolution that seems inevitable.

CURWOOD: E. O. Wilson’s new book is called “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.” Thank you so much, Professor Wilson.

WILSON: Thank you for the opportunity.

Related links:

- E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation

- Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life

- About E. O. Wilson

BirdNote: The Stealthy Shoebill

The African Shoebill. (Photo: Paul W. Sharpe)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Birds come in all shapes and sizes, with feathers drab or colorful – and voices melodious or grating. And periodically, as Mary McCann points out in today's BirdNote®, there are birds that are – well – downright weird.

BirdNote®

What in the World Is a Shoebill?

[SWAMP SOUNDS]

MCCANN: Deep in the dense, remote swamps of Central Africa lives one of the most peculiar looking of all birds. Picture a massive, blue-gray stork, standing up to five feet tall on long, gray legs. But instead of the stork’s long, tapered bill, substitute a prodigious, stout bill that’s hooked at the tip – and that gives this bird its name.

[Shoebill bill clapping and vocal sounds, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/2285, 0.48-54]

Meet the Shoebill, a bird unknown to science until the 19th Century, and the only living member of its family. So named because that comically large bill is, yellow-orange, and shaped like an oversized Dutch wooden shoe. But although the Shoebill looks like it walked right out of a cartoon, its beak is no joke. The edges are sharp enough to behead its prey, which include catfish with hard bony heads as well as lungfish, snakes, and even baby crocodiles. Which Shoebills hunt in the shallows, often standing completely motionless before they strike.

Shoebills resemble storks, but are more closely related to pelicans. (Photo: David Cook)

The Shoebill’s physical resemblance to the stork gave it its early name, the Whale-headed Stork. But DNA analysis showed that it’s more closely related to pelicans — another group of birds whose oversized beaks are truly awe-inspiring. Shoebills are notably less numerous than pelicans, though, with only 8,000 surviving in the wild.

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. [2285] recorded by Marian P. McChesney.

XC320901 ambient sounds recorded by James Bradley, Kenyan Swamp setting.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org November 2016 Narrator: Mary McCann

[Shoebill bill clapping and vocal sounds, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/2285, 0.48-54]

Fun story about a Shoebill: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2274300/Shoebill-appears-smile-released-wild-rescued-poachers.html

Shoebill photos: https://www.google.com/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=shoebill%20photos

http://birdnote.org/show/stealthy-shoebill

CURWOOD: Swoop on over to our website, LOE.org, for some pictures.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote website

- About the Shoebill from the National Audubon Society

- Happy shoebill saved from poachers

[MUSIC: The Mandala Octet, “The Last Elephant, pt.2” on The Last Elephant, Accurate Records]

[SOUND OF WAVES]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week on a secluded beach along the central California coast.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

CURWOOD: The mesmerizing sounds of the Pacific at Big Sur -- if you listen closely - you'll hear some barking sea-lions as well.

[SOUND OF WAVES WITH SEA LIONS]

CURWOOD: Bernie Krause recorded them for his Wild Sanctuary CD, “Ocean Dreams.”

[MUSIC: The Mandala Octet, “The Last Elephant, pt.2” on The Last Elephant, Accurate Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Helen Palmer, Rebecca Redelmeier, Olivia Reardon, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org -- and like us, please, on our Facebook page -- it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth