May 20, 2016

Air Date: May 20, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump: Climate and Paris Skeptic

View the page for this story

Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for President, says he doubts the reality of man-made climate change and if elected he would renegotiate the December 2015 landmark Paris climate agreement. (01:25)

Conservatives Tend To Ignore Liberal Talk About Climate

View the page for this story

In the US political conservatives often express less concern about environmental issues than liberals. But eco-psychologist Christopher Wolsko of Oregon State University tells host Steve Curwood this is due in part to the liberal framing of issues. His studies indicate reframing environmental topics in ways that reflect conservative values such as respect for authority and patriotism can better engage conservatives. (10:50)

The Politics of Teaching Climate Science

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

The majority of Americans are worried about climate change, yet the subject is barely covered in public school science classes. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports on the powerful forces and opinions that make global warming a potential minefield for teachers. (04:55)

Climate Benefits if New Federal Fossil Energy Leases are Banned

View the page for this story

Climate activists are calling on the government to stop leasing federal lands and waters to fossil fuel companies, and new analysis from the Stockholm Environment Institute quantifies the impact that would have on reducing emissions. Senior Scientist Michael Lazarus tells host Steve Curwood that limiting the supply of fossil fuels can reduce the impacts of global warming. (09:15)

BirdNote®: Drinking on the Wing

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Most birds drink standing up, but swallows and swifts dip down over ponds to drink on the wing. In this week’s BirdNote® Michael Stein examines where this adaptation come from. (02:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the environmental news headlines, Peter Dykstra fills in host Steve Curwood about faltering “clean coal” and carbon capture projects and how critics say chemicals manufacturing safety measures are falling short of protecting the public. The history calendar this week brings a tale of how superstition saved lives, when tornadoes battered one Kansas town on the very same date three years in a row. (04:40)

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Checking Up on Native Plants

View the page for this story

Spring brings the first native blooming plants, and native wildflowers are springing up at the New England Wild Flower Society’s Garden in the Woods near Boston. But climate change, aggressive invasive species and insects are stressing some iconic plants, so a group of experts assessed the state of New England’s plants now. We revisit a conversation between host Steve Curwood and the Wild Flower Society’s senior research ecologist Elizabeth Farnsworth, as they walked in the woods to find out what’s going on. (13:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Chris Wolsko, Michael Lazarus, Elizabeth Farnsworth

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Environmental concerns, like global warming, often get a chilly reception from conservative minded voters. The problem may be how these topics are presented.

WOLSKO: Conservatives are not inherently anti-environmental so much as they are chronically rejecting the liberal tone of the prevailing environmental discourse around these issues.

CURWOOD: A new framing could prove more appealing. Also, teaching climate science, often the problem of getting a clear message across is the language in some textbooks.

BERBECO: It depicts scientists as unsure, so ‘scientists think’ not ‘evidence shows’ or ‘research has shown.’ Students come away with a real misunderstanding of climate change. They think scientists are unsure about it, you know they think that there’s a controversy.

CURWOOD: Words, climate and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. Innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Trump: Climate and Paris Skeptic

Donald J. Trump says if he is elected President of the United States this November, he will renegotiate the Paris climate deal. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for President this year has declared that he would renegotiate the American position in the international Paris Agreement to address global warming. And if Mr. Trump is elected and follows through on this pledge, it would deal a heavy blow to this December 2015 deal made among nearly 200 nations. Speaking to reporters for Thomson Reuters, Mr. Trump said that pact is bad for the US and “at a minimum I will be renegotiating those agreements. And at a maximum I may do something else.”

In March Mr. Trump went on the record as a skeptic of the dangers of human related climate disruption, when he spoke to the editorial board of the Washington Post.

Seen here departing from his private plane, Trump has in the past called climate change a “hoax” devised by the Chinese government to bring down the U.S. economy. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

TRUMP: I think there is a change in weather. I am not a great believer in man-made climate change. I’m not a great believer. There is certainly a change in weather that goes – if you look, they had global cooling in the 1920s and now they have global warming, although now they don’t know if they have global warming. They call it all sorts of different things; now they’re using “extreme weather” I guess more than any other phrase. I am not – I mean I know it hurts me with this room, and I know it’s probably a killer with this room – but I am not a believer. Perhaps there’s a minor effect, but I’m not a big believer in man-made climate change.

CURWOOD: Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump, interviewed by the Washington Post editorial board on March 22nd of this year.

Related links:

- Reuters: “Skeptical Trump says would renegotiate global climate deal”

- The Washington Post: “Trump: ‘I’m not a big believer in man-made climate change.’”

- The Guardian: “Trump won’t be able to derail Paris climate deal, says senior US official”

Conservatives Tend To Ignore Liberal Talk About Climate

Wolsko presented the “binding” group in his study with a message linking patriotism with protecting the environment, alongside an image of a flag waving in front of a distant mountain peak. (Photo: Matt Artz, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Mr. Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again,” evokes values of patriotism and defending American prestige, appeals that resonate with conservatives. And speaking to those moral ideals is also a way that conservatives can be drawn into environmental protection and conservation, says Oregon State University assistant professor Christopher Wolsko.

Professor Wolsko calls himself an eco-psychologist and has been studying how liberal and conservative value systems affect environmental politics, especially regarding climate change. He says his research shows the present framing of environmental issues with largely liberal values tends to exclude conservatives who might otherwise embrace them. Chris Wolsko joins us now; welcome to Living on Earth.

WOLSKO: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why did you want to look at how reframing climate change to better reflect conservative values, conservative parlance, might have an effect on how they respond to that and other environmental issues?

WOLSKO: In one sense it was really just a basic exploration of persuasion and message framing processes in social psychological experimentation. In another sense it is an example, arena, of what I would consider to be the absurd or overly extrematized, political polarization that we see across a number of social environmental issues. Environmental issues just happen to be of concern to me, and what we see generally in terms of the political polarization on environmental issues, I’m sure many people are aware of, is just a strong, strong correlation between identifying as liberal and saying you practice a variety of conservation behaviors, and indicating that you believe in climate change and are concerned about it, and identifying as conservative and kind of doing the opposite.

Wolsko also used an image of a bald eagle in his study, as the national bird symbolizes patriotism for many Americans. (Photo: Jerry McFarland, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: As I understand it, you’re really looking at moral framings of these issues.

WOLSKO: That’s right. So in research and actual practice of persuasion out there in the world, people frame things in all sorts of different ways. Commonly we see things like fear appeals, both in an environmental messaging, as well as in public health messaging, as well as in getting people to buy a certain kind of beer for fear they’ll be rejected if they don’t, so that’s a common...There’s a whole range of appeals...and we were looking at moral framing because there was some new content analyses of media reports that really tended to reflect the fact that contemporary discourse on environmental issues tends to be discussed in liberal moral values rather than those that tend to appeal to conservatives to a greater extent.

CURWOOD: OK, so what are the liberal moral values?

WOLSKO: Liberal moral values tend to focus on fairness and justice concerns, and concerns about whether individuals are being harmed or cared for. As a package they’re referred to in the context of moral foundations theory as “individualizing” moral concerns, so protecting the rights and integrity of individual lives.

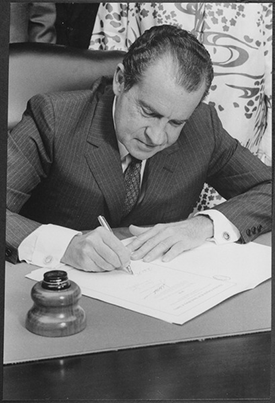

Conservative politicians helped bring key environmental laws into existence: President Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act into law in 1970. (Photo: Oliver F. Atkins, CC government work)

CURWOOD: And conservatives?

WOLSKO: Conservatives tend to be concerned with those values as well but also perhaps more strongly emphasize what moral foundations theorists have called “binding” moral values, so these are the ties that bind, that draws into important social groups and what-not, so things like in-group loyalty, respect for authority, and concerns about the purity and sanctity of human endeavors, so thing like resisting overly hedonic behaviors in a way that would kind of throw the group out of balance if everyone was kind of seeking their own personal desires.

CURWOOD: You know, over the past 40 plus years since that first Earth Day, the environmental issues have been cast by the media and certain advocacy organizations. How much do you think their approach to this issue has led to this polarization we see, that using values that don’t resonate with conservatives?

WOLSKO: I think it has a lot to do with it. You know, conservative media sources are just as responsible in their own way by derogating liberal framing, you know, vice versa. So both the angles are happening. In this particular case, environmentalism has been largely championed as this politically liberal cause and because liberals tend to value these moral frames of fairness, justice, harm, and care, a lot of the discourse around environmentalism has focused on these values to the exclusion of conservative values. So I think that’s a great error and my hypothesis is that conservatives are not inherently anti-environmental so much as they are chronically rejecting the liberal tone of the prevailing environmental discourse around these issues.

CURWOOD: As part of a social psychology experiment on the framing of climate change, Professor Wolsko recruited 185 people across the political spectrum. Then he randomly assigned them to one of three groups, and presented each of the groups with value-oriented environmental messages.

One group saw calls to action that emphasized liberal values like fairness and justice, and who might be harmed. He termed that group “individualizing”. The second group saw messages that highlighted loyalty, respect for authority, and pride in the United States, and he called them the “binding” group.

The final control group just received a brief generic call to address environmental issues. Again, Professor Wolsko.

Greater awareness of the ways that climate change and other environmental issues are framed is key to a bipartisan conversation on these issues, Wolsko says. (Photo: Bo Insogna, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

WOLSKO: Essentially what we found in the control and in the individualizing condition was the typical political polarization that we see on public opinion polls and what not.

CURWOOD: So what’s that?

WOLSKO: In relationship to climate change – and I had a multi-dimensional measure of climate change. So in relationship to that measure, conservatives tended to report being less concerned about the effects of climate change, tended to believe that it was happening less, tended to believe that it was more caused by natural cycles rather than human-caused, and liberals were just the opposite, so that typical political polarization, quite strong correlations between political identity which was measured before the manipulations and these measures of climate change. We also asked about conservation behaviors, how likely are you to engage in a variety of different behaviors like recycling, like composting, using green products such as compact fluorescent lightbulbs, things of that nature. We also asked in a more recent study about connectedness to nature which is not typical conservation behavior at all. It’s just more of an experiential sense that one has a positive relationship with the natural environment, and also in that case, in both control and in individualizing conditions, we saw a polarity such that conservatives said they were less connected to nature and less likely to engage in these conservation behaviors than did liberals.

CURWOOD: So how did people respond to the other way you framed things?

WOLSKO: So in terms of the binding morality, what we found was that conservatives in that condition, relative to conservatives in the other two conditions, tended to report greater belief in climate change, tended to report that they thought climate change was more caused by human-induced processes relative to natural cycles. They tended to report greater likelihood of engaging in a variety of conservation behaviors. In terms of connectedness to Nature, they also tended to report feeling more connected to the natural environment.

CURWOOD: Chris, if the phone were to ring after the interview and an environmental organization or advocates called you up and said, “Please, help us reframe what we’re talking about for conservatives, particularly around climate change,” what advice would you give them?

WOLSKO: Well, on one hand, a big part of the problem why we see such divisive political polarization around a number of other social issues, as well as these environmental issues, is because we chronically segment the market share that we’re interested in targeting and tell those people what we think they want to hear from who we think they want to hear it from. The problem with that long term is that it creates this, you know, separate reality. It’s very manipulative. It’s very much for the short-term gain of someone agreeing with your position and/or donating to your cause. I think what we need actually is a more inclusive dialog that includes this whole range of moral values in any appeal, so that we can simultaneously, first of all, be aware of this range of moral values, affirm our own ones that are particularly important to us, and tolerate and respect those that are important to others. So in some current research that I have under review, I’ve actually attempted to come up with this sort of frame that both affirms liberal and conservative moral values, but does so in an inclusive sort of way, and I’m seeing similar if not better responses.

Christopher Wolsko teaches ecopsychology at Oregon State University-Cascades. (Photo: OSU Cascades)

CURWOOD: So tell me, how do you frame this in a way that’s inclusive for both liberals and conservatives?

WOLSKO: Well my first effort in this regard has been to explicitly tell the target audience that liberal values have traditionally dominated the discussion of environmental issues and that conservative values are actually uniquely situated to address environmental issues as well. I use a slogan called “Conservative Values, Conserving the Environment,” and I go through and list the number of conservative values that previous research might suggest would be appealing in this regard and have people read through them and have both liberal and conservative audiences look through and choose ones that they feel might unite all people across the political spectrum on environmental issues and, interestingly, the one that comes up is personal responsibility. That’s a big one. So take personal responsibility for yourself, for your family, for the land that you call home, and this seems to be an overlapping value that both liberals and conservatives can agree upon as really important for promoting pro-environmental causes.

CURWOOD: And what are some of the other mutually acceptable values?

WOLSKO: A couple of the other values championed both by liberals and conservatives included making your own decisions on local land and water issues in the best interests of families rather than leaving it to bureaucrats, respecting your elders and teaching your children good values about taking care of the environment, and also working hard and playing hard in the great outdoors. So part of the purposes of this new research was to come up with this inclusive set of values, as well as to just model a persuasive message that doesn’t try to manipulate but tries to encourage this discourse around finding solutions that appeal to both liberals and conservatives, even though they might not be identical.

CURWOOD: Christopher Wolsko teaches eco-psychology at Oregon State University in Bend Oregon. Thank you so much!

WOLSKO: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read the paper: “Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors”

- About Christopher Wolsko

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before (aka Star Trek),” Plectrasonics, Alexander Courage/arr.Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, SoundArt Recordings/CMH Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, communicating climate reality to school kids in the face of skepticism. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Cuban Landscape With Rain,” Plectrasonics, Leo Brouwer/arr.Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, SoundArt Recordings/CMH Records]

The Politics of Teaching Climate Science

Climate activists see bringing climate change into the classroom as a simple matter of updating the science curriculum. But a recent survey revealed that science teachers are often ill-equipped to deal with the subject. (Photo: NL Monteiro, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When it comes to concern about global warming, a Gallup poll from March this year found that 64-percent of Americans are fairly or very worried about it. That’s the highest percentage in some eight years. But in our schools, a February survey published in the journal Science showed that most high school science teachers spend basically only an hour or two a year teaching about climate change. And when they do, it can mean trouble. The Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant has our story.

GRANT: Craig Whipkey isn’t always the most popular guy at Central Valley High School, about 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, in Beaver County. He teaches environmental science in this old steel region, and gets called “tree hugger” a lot. Just a few weeks ago, after he took students on a field trip to an environmental center…

WHIPKEY: I had a student come up to me and the young lady informed me that her dad was coming to pick her up, but would I mind going somewhere else, because her dad didn’t like me very much.

GRANT: Whipkey’s gotten used to it. Nearly ten years ago, when he started teaching high school science, he trained with Al Gore’s Climate Reality Project. He brought the climate science back to his students, and some of them started talking about it at home. One parent, a leader in the local Republican Party, even wrote an editorial in the Beaver County Times complaining about Whipkey.

That’s when higher ups in the Central Valley school district took notice. They called him in to review his lesson plans.

WHIPKEY: I was a second year teacher, and I was teaching a brand new course, and the school board and the administration wanted to look at my materials. Absolutely, I was sweating.

GRANT: And Whipkey’s not alone. Other Pennsylvania science teachers have been challenged for teaching climate change. Many times, it becomes an issue when a district is ordering new textbooks. Just last month, members of the Quakertown area school board, north of Philadelphia, refused to order the environmental science and oceanography books requested by the district’s administration. They didn’t like that students would be taught climate change as a scientific fact. Quakertown Board members declined to talk with us for this story.

But something similar happened in the Saucon Valley School District, south of Allentown. Bryan Eichfeld, a school board member there, calls climate change a hoax, and a political issue. He wants textbooks that provide competing views.

A rally for climate education (Photo: Joe Brusky, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

EICHFELD: That’s not what’s happening with climate change. They are taking everything that they can to prove that there’s climate change and ignoring the data that disproves it.

GRANT: Science teachers in Eichfeld’s own district, and at the national level say, there is no other side. This isn’t politics. It’s science based on data and evidence. Minda Berbeco is policy director with the National Center for Science Education. She takes issues when school board members call the lack of balance “unfair.”

BERBECO: You know, it’s really unfair not to teach kids the accurate science. It’s really unfair to not demonstrate what the evidence shows and what the data shows.

GRANT: Berbeco says when school boards choose science textbooks, they’re really deciding how students will understand climate change. For example, researchers surveyed four middle school science textbooks in California, and they found a lot of wishy- washy language.

BERBECO: It depicts scientists as unsure, so ‘scientists think’ not ‘evidence shows’ or ‘research has shown.’ Students come away with a real misunderstanding of climate change. They think scientists are unsure about it, you know, they think that there’s a controversy.

GRANT: And beyond textbooks, many teachers don’t know enough about climate change themselves, and don’t feel confident teaching it. David Evans is director of the National Association of Science Teachers. He says the average teacher graduated in the early 1990s.

EVANS: And honestly twenty years ago climate science, in fact most environmental science was not very heavily featured in teacher preparation programs.

GRANT: Plus, in Pennsylvania, the incentive is low. Many states have passed new science standards that include climate change, but not Pennsylvania. And the Biology Keystone exam, a test that teachers must prepare students to take, doesn’t really address climate change either.

Julie Grant reports for the Allegheny Front (Photo: Allegheny Front)

Teacher Craig Whipkey, that tree hugger in western Pennsylvania, says there are plenty of reasons teachers choose to skip climate change.

WHIPKEY: I think it is ‘don’t rock the boat,’ I think it’s the easiest path, I think it is, however you want to put it, it doesn’t get a lot of press that it’s not in there, but it would get a lot of press if it was in there.

GRANT: Whipkey says it’s too bad because young people will need to understand climate change to make informed decisions in the future. Still, he’s optimistic. He says the superintendent and school board members who gave him trouble when he first started teaching climate science ten years ago have all been replaced. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Check out the story at the Allegheny Front

- Science Magazine survey on climate education

Climate Benefits if New Federal Fossil Energy Leases are Banned

The overwhelming majority of coal reserves in the extensive Powder River Basin, located in Wyoming and Montana, are owned by the federal government. (Photo: Jeremy Buckingham, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Thousands of climate activists across the globe this month have been protesting the continuing use of fossil fuels. In the US, they have blocked rail lines, protested at refineries and at a federal government auction of oil and gas leases. They point to the rise in US fossil fuel production, much of it for export, even as domestic consumption of oil, gas, and coal has been falling. Activists call for fossil fuels to be “kept it in the ground”, especially on public lands where the industry already leases over 67 million acres. To explain what it might mean for climate protection if the US were to stop leasing federal lands and waters for mining and drilling, we turn to Michael Lazarus, US director of the Stockholm Environment Institute.

I stopped by his office in Seattle the other day, and asked him to discuss a study his group recently completed that shows how much reducing the US supply of fossil fuel would lower world greenhouse gas emissions.

Michael Lazarus, welcome to Living on Earth.

LAZARUS: Hi, Steve, great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, what prompted you to look into this question of what it would mean to deny new leases of fossil fuels on public lands here in the US?

Environmental campaigners are calling for an end to oil leasing in the Gulf of Mexico, not just because of climate change, but the risks of oil spills like Deepwater Horizon. (Photo: Green Fire Productions, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

LAZARUS: Well we looked at that question as part of a broader question. What does it mean to continue to invest in fossil fuel production around the world? Because we think there's been a blind spot. For many years now we've been focused on how much fossil fuels we consume which is the major contributor to climate change, the combustion of fossil fuels, and we've done a lot to think about how we can reduce our consumption and develop alternative sources of energy like renewable energy that are low carbon. At the same time we kind of left the back door open over the past few years and fossil fuels, we thought, you know, they were going to run out. We had heard lots of talk about, you know, peak oil which perhaps was overdone but the idea was that we were running out of these resources about the same time as we were developing new ones. Well it turned out quite differently over the past 10 years. We've seen here in the US the boom in shale oil and shale gas production that was unanticipated 10 or 15 years ago. The problem is that, while that may be good for things like reducing oil imports, it also undermines our efforts to develop these other technologies. It undermines our ability to get people off of their addiction to fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: So set in context for me how important is fossil fuel production in the US compared to the rest of the world.

LAZARUS: Well, interestingly enough, now the US is the number one producer of fossil fuels globally. We're now number one in oil; we’re number one in natural gas, and we're number two in coal. And so in a sense we both have the opportunity to reverse direction a little bit here or make ourselves a little bit more consistent with our climate commitments which we've yet to do. We also have an opportunity to signal to the rest the world that we're serious about addressing both the consumption and production of fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: So when you looked at what it would mean for coal, oil and gas production, if the US stopped granting new leases and stopped renewing them, what did you find?

LAZARUS: We found two things. We found first of all that it would make a contribution towards getting us on a production, fossil fuel production, pathway, closer to the types of targets that we agreed to when Senator Kerry signed onto the Paris agreement just a few weeks ago, that is getting towards keeping global temperature increase to well below two degrees, ideally 1.5 degrees. That requires a reduction in US production, most likely of about 50-percent by 2040 and aiming towards zero in the second half of this century. Meanwhile, US fossil production has been growing and is projected to continue to grow even with the Clean Power Plan and so forth. So we found that you can begin to contribute to turning the corner on US fossil fuel production by ceasing these new leases, and we also found that doing so would lead to tangible emission reductions globally and in the US.

A fossil fuels protester (Photo: Melanie Lazarow, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What kinds of reductions are we talking about here?

LAZARUS: We're talking about for the year 2030, about 100 million metric tons of CO2 per year in reductions and increasing over time, as these new leases would have otherwise begin to produce more and more fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: A hundred million metric tons. Tell me what that means in lay terms.

LAZARUS: OK, a hundred million metric tons. The US every year today produces between six and seven billion metric tons of CO2. So we're talking about one or two percent of our emissions. So it's not the whole thing, but it's quite a significant contribution when you compare what you can do with other policies that have been enacted or may soon be enacted like the Clean Power Plan that would reduce emissions from the electricity sector, increased fuel economy standards for vehicles. Those policies range anywhere from 50 to 600 million metric tons per year of reductions on that same timescale.

CURWOOD: So why do you think that the question of looking at the supply of fossil fuel has been relatively ignored compared to looking at the demand-side?

Tim DeChristopher went to prison for bidding on a parcel of land being leased for fossil fuel extraction. (Photo: Rainforest Action Network, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LAZARUS: It's politically challenging. You know the head of the OECD, an international economic organization that’s well-known, Angel Gurria, had this great speech of three years ago where he talked about this phenomenon of “carbon entanglement”. Carbon entitlement is sort of the dependency that the communities and countries have on the profits, the rents, the revenues, the royalties that are collected from fossil fuel production. And that dependency makes it very hard for countries to just engage in this question. You always want other countries to go first. It's another manifestation of this collective action problem that we have with climate change. We always wait for the other person to go first. Instead we need to turn that around, show leadership, and, because the world is getting increasingly serious about addressing climate, as we saw in the 170 countries signing on to the Paris agreement with its greater ambition, I think the tide is beginning to turn.

CURWOOD: And then to quote President Bush, the 43rd President of the United States, “we're addicted to oil,” and perhaps the prospect of having the supply reduced is scary to addicts.

LAZARUS: Indeed. Indeed, and so that's why it's all the more important to understand that there is something else out there that is a better life, as it were, without as much fossil fuels and we've seen that develop with the radical reduction in the cost of solar power. We're seeing it in communities that are showing that they can move away from fossil fuel use. We are affiliated with this Swedish Bay Stockholm Environment Institute, we are, and when I go there there's talk about a fossil free Sweden, and zero emissions there, and they've gotten a long way towards it. And so there are examples across the world of communities that are thriving, and that's in a sense how you break the addiction.

CURWOOD: So overall, Michael Lazarus, how optimistic are you that this approach looking at winding down the leasing of public lands for energy extraction will produce the desired results?

Michael Lazarus is U.S. Centre Director of the Stockholm Environment Institute. (Photo: Stockholm Environment Institute)

LAZARUS: Well, let's step it back to what are the desired results here, and I think the desired result in my mind is to develop a suite of policies that get us on a path closer to what we agreed to in the Paris Agreement, which is basically a phase-out of fossil feel use in the second half of the century. And if we are serious about that, then we need to begin phasing down fossil fuel production across the US. Federal lands and waters is an ideal place to begin thinking about that because the federal government has the authority, can set the signal. We’ve seen that further investment in fossil fuel production has led to great expansions in recent years of production. If we continue to do that, it makes it much harder to transition to renewable energy, to implement energy efficiency policies, so am I optimistic that, if enacted, measures like this? They, yes, they would get us far closer and they would close this sort of gaping gap between what we're doing to reduce the demand for fossil fuels and what we have yet to do and begin to think about in terms of reducing the supply.

CURWOOD: Michael Lazarus is the US director of the Stockholm Environment Institute. Thank you so much, Michael.

LAZARUS: Thank you, Steve. Great talking to you.

Related links:

- Read the working paper: “How would phasing out U.S. federal leases for fossil fuels extraction affect CO2 emissions and 2°C goals?”

- Listen to LOE’s conversation on the introduction of the Keep it in the Ground Act

- Listen to LOE’s interview with Michael Brune on “Keep it in the Ground”

- About Michael Lazarus

BirdNote®: Drinking on the Wing

A tree swallow dipping down for a drink (Photo: Nicholas Sanchez, Creative Commons 2.0)

BIRDNOTE®/DRINKING ON THE WING

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: As the days and evenings grow longer, and the weather entices us outside, the twittering of swifts and swallows overhead catches our ear. And as Michael Stein explains in this BirdNote®, if we pay close attention to them – we’ll notice something unusual.

BirdNote®

Drinking on the Wing

[Tree Swallow song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/137594, 0.06-.10]

As a Tree Swallow swoops gracefully across a marsh, its long, slender wings glint a deep, iridescent blue. It glides close to the surface, tips its head down, and lightly skims the pond for a second with its beak open. Drinking – on the wing.

[Tree Swallow calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/94428]

Many birds drink while standing: dipping their beaks into a pond or birdbath, taking a beakful, and then tossing their heads back to swallow the water. And most birds can’t pull off a daredevil, in-flight drink because they just aren’t built for it. Swallows are such virtuosos of flight that their skimming the pond almost looks like showing off. [Tree Swallow calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/94428]

Drinking on the wing suits swallows best. They walk awkwardly on the ground on rather short legs, and their long wings are pretty cumbersome. So it’s far more efficient to grab a drink on the glide. This adaptation holds true for some other birds, too.

A barn swallow perched on a branch in Colorado (Photo: One Heart Art, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[Common Nighthawk calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/516732]

Common Nighthawks are much bigger than swallows, with a two-foot wingspan. They take their water in flight, too. While swifts, with an even longer-winged structure than swallows, have such short legs that they never land on the ground, and so a sip on the wing is all but essential. I’m Michael Stein.

[Chimney Swift calls, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/5995, 0.07-.09]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Tree Swallow [137594] recorded by Gerrit Vyn; Tree Swallow [94428] and Common Nighthawk [516732] recorded by W L Hershberger; Chimney Swift [5995] recorded by G B Reynard

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org May 2016 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/drinking-wing

CURWOOD: For pictures, glide on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Check out the story on the BirdNote® website

- Read more about tree swallows

CURWOOD: Coming up...Walking the muddy pathways of the New England woods. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Derek Trucks Band, “Afro Blue,” Roadsongs - CD1, Mongo Santamaria, Sony Masterworks]

Beyond the Headlines

Kemper carbon capture project construction (Photo: XTUV0010, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Let’s see what’s happening in the world beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org is waiting on the line from Conyers Georgia to fill us in. Hello, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hello, Steve. The coal industry had an average week by its own recent standards, which means it was a very bad week indeed, particularly with government efforts to boost carbon capture and storage, a key element in the difficult search for what they call “clean coal.”

CURWOOD: Ah, of course many critics say clean coal and carbon capture are either too difficult or just too costly to achieve.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, especially when the government quits the effort. The Energy Department was the largest investor, with a few private partners, in the Texas Clean Energy Project, and so far this year DOE has denied a request for a cash advance and written the Texas project out of next year’s budget -- not a death blow, but hardly a vote of confidence to entice new investors. DOE’s Inspector General investigated and filed a report in April, saying DOE is concerned about the viability of the whole project, which is already two years behind schedule.

CURWOOD: I don’t really want to ask this question, Peter, but as taxpayers, how much are we into this deal?

DYKSTRA: Ah, it’s only $450 million. But of course then there’s the $234 million committed to the Kemper carbon capture plant in Mississippi, which is also struggling to meet its budget and its timetable. And the Kemper plant is now reportedly the object of an SEC investigation. Not the SEC college football conference, but the Securities and Exchange Commission. They’re looking into disclosures and also the legally-required financial reporting on the whole project. And one more twist in the coal world, this one’s from Southern Illinois.

CURWOOD: Huh, the Midwest Coal Country… What’s up there?

DYKSTRA: Well, the biggest newspaper in the region is the Southern Illinoisan in the city of -- Carbondale – and it published an editorial last week praising coal miners and the region’s coal heritage, but also offering a dose of reality for the area’s biggest industry as well as its Democratic State Representative, John Bradley:

“At some point,” they wrote, “coal jobs in Southern Illinois will go away entirely. Your legislator cannot – or will not – admit that. Deep down, we all know it’s true.”

CURWOOD: But there are huge challenges for them – I mean, they’re giving up a way of life, and finding livelihoods to replace it, when they’ve sacrificed so much for us – including their lives and their health – to make our modern industrial society possible.

DYKSTRA: Right. The editorial delivered the harsh reality of coal’s future, and while I don’t always dive into the comment strings on news sites, the comments here suggest that feelings in coal country are harsher still.

CURWOOD: Huh, sounds like coal country is in a black mood. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Well, here’s a pattern we all recognize — the Obama Administration’s EPA goes where the Bush Administration’s EPA wouldn’t dare go, and prominent Republicans lambaste them for it. But here’s a little switch on the theme.

An aerial photo taken several days after the West Fertilizer Company explosion (Photo: Shane.torgeson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Oh?

DYKSTRA: Republican Christine Todd Whitman, the former New Jersey Governor who ran the EPA in the early years of the George W. Bush administration, has written to current EPA chief Gina McCarthy that the current plans to reduce chemical plant explosions are too weak.

CURWOOD: So, what’s she talking about here -- chemical plant accidents, possible terrorism?

DYKSTRA: She’s talking about both. Gov. Whitman says that a concept known as IST – Inherently Safer Technologies – gets the short shrift in the Obama administration’s chemical safety upgrades. And she’s not the only one. Lisa Jackson, who was McCarthy’s EPA predecessor under President Obama, has also called for stronger measures, echoing what a young U.S. Senator named Barack Obama said in 2006, when he called hazardous chemical facilities, ”stationary weapons of mass destruction spread all across the country.”

CURWOOD: Hmm. Everybody’s talking about it. Nobody doing anything about it. Hey, what do you have from the history vault this week?

DYKSTRA: A bizarre instance where superstition probably saved lives. It was 100 years ago this week, May 20, 1916, a tornado hit the plains town of Codell, Kansas. They estimate it was an F2 tornado and it caused plenty of property damage in the town, but no deaths. Then a year to the day later, on May 20, 1917, an F3 tornado grazed the outskirts of the town – a big storm, a little damage. Again, no deaths, and you’ll never guess what happened a year later to the day on May 20, 1918.

A tornado bore down on the town of Ellis, Kansas in 1917 (Photo: NSSL NOAA, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: I sense a pattern here.

DYKSTRA: Exactly. That day an estimated F4 tornado leveled the town’s hotel and school and quite a few homes and also barns and outhouses, but thanks to the widely-accepted superstition that things always come in threes, people took to their storm cellars at the first sign of bad weather. This was a pretty nasty twister, and there were some deaths in other towns because of that twister, but only minor injuries in Codell.

CURWOOD: Well, we all avoid walking under those ladders, don’t we?

DYKSTRA: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org – and DailyClimate. Thanks, Peter, we’ll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- InsideClimate News: “Energy Department Suspends Funding for Texas Carbon Capture Project, Igniting Debate”

- Department of Energy Office of Inspector General Special Report on Texas clean energy project

- “SEC investigates Mississippi Power over Kemper costs”

- The Southern Illinoisan: “Voice of the Southern: A future without coal?”

- “Bush EPA Head Says Obama Chemical Safety Plan Is Too Weak”

- American Chemical Society statement on Inherently Safer Technology

- The Kansas Historical Society on Codell, Kansas’ triple tornado whammy

[MUSIC: Peter Pringle, “Over the Rainbow,” www.peterpringle.com, Harold Arlen]

Checking Up on Native Plants

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

The Curtis Woodland Garden, Garden in the Woods in Framingham, Massachusetts. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: Last year we took advantage of the spring weather to head out to one of our local treasures - the Garden of the Woods, the showcase and laboratory for the New England Wildflower Society.

There are some 3,500 species and subspecies of native plants in the region that are used to tough winters, though they are under stress from climate change, development and invasives. We arranged to meet Elizabeth Farnsworth, the Senior Research Ecologist for the New England Wild Flower Society at its 30 acre woodland garden. She’s the lead author of the “State of the Plants Report” - the most comprehensive assessment of native plants and plant communities ever assembled in the region.

[WALKING OUTDOORS, BIRDS CHIRPING]

Hi there, I’m Steve Curwood. Hi.

FARNSWORTH: Hi, Steve. Nice to meet you.

CURWOOD: And you are Elizabeth Farnsworth?

The alpine region is one of the habitats described in the New England State of the Plants report. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Yes, indeed.

CURWOOD: We're here at the Garden in the Woods. So what's here?

FARNSWORTH: So what we have here is one of the most beautiful naturalistic gardens, one of the oldest in eastern North America. It has a wonderful selection of native plants that, of course, you can use in your own garden, but also that are broadly representative of the habitats of New England. So we've tried to really re-create the diversity of the different habitats, from bogs, we have this beautiful pond here, we have a sand plain habitat that we just installed, so a whole range of different types of plantings.

CURWOOD: Now why do native plants matter? There are wonderful plants like the daffodils and tulips that come from elsewhere that grace gardens. So why are native plants so important?

The New England Wild Flower Society's Garden in the Woods in full bloom. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Native plants evolved here. They evolved in these climates in the peculiar habitats of New England and all of the organisms that depend on them co-evolved with these plants. And so if you look at the tulips in your garden or the daffodils in your garden, how many bees are actually visiting those, how many butterflies are coming in to actually pollinate those plants? Versus if you look at some native plants all around you, you'll notice that diversity is really attractive to them.

CURWOOD: So you recently completed a study of the region's plant life, how well it's doing, native, non-native, invasive, all that sort of thing. In brief, how are native plants doing in this region?

FARNSWORTH: So about 22-percent of our native flora are regarded as rare, that is endangered, threatened, special concern, or even historic in one or more new England state. So close to 100 species, about 96 species, are now no longer known from New England. They may exist elsewhere somewhat precariously, but they're no longer here and that's a pretty substantial number. The majority of our flora is, in fact, native. About 30-percent have been brought from elsewhere or introduced purposefully or mistakenly. That's about on par with other regions of the country, but about 10 percent of that set of non-native species are regarded as invasive. So that's 111 species.

CURWOOD: Invasive means trouble?

Northern hardwoods (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Invasive means that these are plants that can grow quite aggressively. They can overtake native plants, they can outcompete them. They can come to dominate a particular habitat, so it becomes very impoverished in terms of plant diversity and often animal diversity.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the big ones, what about trees, how are they doing in this region?

FARNSWORTH: Well, trees are facing a number stresses, and it's actually a good example right here at the garden. We have had to remove a number of hemlock trees. These hemlock trees have been attacked by these tiny white insects, the hemlock woolly adelgid, which is spreading across New England. It's beginning to be seen even farther north. We have the ash trees, which are being affected by the emerald ash borer, which is on our doorstep, moving into western portions of New England. We have sugar maples that are showing some signs of being stressed by warmer temperatures, not necessarily pests or pathogens yet, but a lot of the climate models do predict a northward sort of contraction of the range of Sugar Maples, and that's, of course, an iconic tree for New England but also very important to our economy.

A riparian zone is a wetland area, often the adjacent to rivers and streams. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: As I look around, I see some big trees here, like there's this big red oak. How are these trees doing?

FARNSWORTH: Red oaks are holding their own so far. We're worried about sudden oak death which, of course, is the scourge of oaks in California with people transporting wood and potentially transporting disease. Red oaks, of course, we may remember that certain caterpillars really ravaged them, particularly in the 60s. Gypsy moth caterpillars, I can recall from my childhood, just listening to the rain of caterpillar frass and complete defoliation of these trees, but they're pretty resilient. These guys have been here for probably 150 years, and they’re doing OK. Many of the climate models suggest that, as the temperatures warm, that oaks and hickories will become much more dominant on the landscape. Trees which now, you know, tend to be dominant further south are likely to be moving into our area even as some of our more northern adapted species begin to contract north.

CURWOOD: So tell me more about climate change. What did you find when you did this evaluation of the plants, the flora, as you scientists call it, in this region? How is climate affecting things?

New England salt marsh (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: We're already seeing the effects of shorter winters and warmer springs, drier summers. Plants on average are flowering, many of them, two weeks earlier in the spring. So, we're already picking up the signal but certain plants are responding very strongly to climate change and, in fact, some of our invasive species are responding more strongly than some of our native species. So, there's sort of winners and losers in terms of how flexibly plants can actually adapt to climate change. So we understand that's going to contribute to shifting in our natural communities. It also, the flowering behavior, of course, is really important to pollinators and so if there is an offset between early flowering plants and the emergence of their pollinators, both parties are going to be unhappy.

CURWOOD: What has flowered early in the Garden in the Woods that you think you might at tribute to climate disruption?

FARNSWORTH: Well, we are starting to see the emergence of these beautiful plants call Bloodroot that are members of the poppy family. When those flowers pop out, they’re going to be a very big and white.

CURWOOD: Are these guys early this year, or are they on time?

Sand plains cover a good deal of New England habitat, some of which is thanks to development in the region. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: I think they're actually a bit late this year. Climate change is a long-term phenomenon with a lot of very ability between years, as we've seen. The garden is relatively recently free of snow, but if you compare this to two years ago when we had a very mild winter, many of these plants would've been fully in flower or even finished flowering or even close to in-fruit by this time, so these plants are highly sensitive to the temperatures.

CURWOOD: So, let's take a look around this pond here. So how are ponds, sides of rivers, wet areas, doing in terms of native plants here in the region?

FARNSWORTH: Well, it kind of depends on what type of wet area you're talking about. But, for example, ponds are doing moderately well, although acid rain has changed the chemistry, particularly of our northern ponds, so that they are much more acidic. They can't really support a lot of the plants that used to live alongside the pond or even in the pond, so they are pretty species-poor. Some ponds are beginning to recover, which is good news. Other wet areas, one of which that we covered in our report, are riverside areas, so floodplains, sandbars, those very changeable habitats that occupy river systems. And they're extremely productive, they're very, very, rich and they of course do help with flood control.

[WALKING]

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Sarracenia purpurea is a purple pitcher plant found around bogs. It's carnivorous and feeds on small insects. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

Now for something completely different this is a sand plain community. It is an extremely dry habitat. Think of Cape Cod, think of Martha's Vineyard, think of much of southern New England where the glaciers kind of dumped their sandy load. You'll see the plants that are growing on this landscape are kind of low and scraggly, pitch pine here. We have some nitrogen-fixing plants here like bayberry so they're some of the first pioneers that can come into these really, really nutrient poor habitats, very dry habitats and survive.

CURWOOD: So in your study how are these plants doing? How is this biome doing?

FARNSWORTH: So sand plant habitats are really great for building things like cities and airports and suburbs because, of course, sandy soils perk, they tend to be nice and flat. So we've lost about 60-percent of the sand plains that were known from New England when the colonial settlers came in.

CURWOOD: So, this looks like cactus.

FARNSWORTH: Believe it or not we have a native cactus species in New England, and it is considered one of our rarest species. This is an Opuntia. It's a prickly pear cactus, and it grows in these tremendously dry, sand-plain kinds of environments, sand dunes, other areas along the coast, and it's only known from a few populations in New England.

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Garden in the Woods reproduced a sand plain habitat showcasing different varieties of native plants that grow in dry, sandy conditions. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

[BACKGROUND SOUNDS OF GARDEN VISITORS]

So one of the reasons that we feature these habitat gardens is to give people an idea of what kinds of native plants could grow in their own particular growing conditions. They'll grow up a lot better than that non-native barberry that you're trying to get started.

CURWOOD: Now, we're here in New England which is its own special place, but somebody listening to us in, say, New Mexico or California or Colorado...What would you suggest to them?

FARNSWORTH: I would suggest much of the same thing that we're doing here in New England and, in fact, by writing the report, we really wanted to begin a national conversation. You know, each of the different states are sort of doing their own thing, some states working harder than others to really maintain their native flora. Some states have more resources than others. Perhaps we can collaborate. California has its share of floodplain habitats that are being impacted. New Mexico has its share of sand plain habitats they're being impacted. So there are important lessons that really cross state boundaries.

Fall in Framingham, Massachusetts' Garden in the Woods. Several varieties of trees surround their lily pond. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

[BIRDCALLS]

CURWOOD: So, what's the risk of not knowing about plants around us?

FARNSWORTH: When you don't know the plants around you, you won't know what you've lost when they're actually gone due to habitat destruction or disease or climate change, any of these threats. So it's really important that we understand that the plants are the foundation and when you start losing important species and this diversity of species then pretty soon, you know, Rachel Carson alluded to many, many years ago, you won't hear the birds, you won't start to encounter the animals, you won't see the butterflies, and then you make get an inkling of just how impoverished the natural community around you has become.

CURWOOD: What do you folks doing terms of seed saving if you're concerned about a species going away?

FARNSWORTH: So we do have a very active seed collection program. We are the largest seed bank for rare plants in the region, and we have both volunteers and staff who go out and collect seed very prudently from rare plant populations. You never collect from more than 10-percent of the plants, but we do maintain them in seed banks. They are something of a bet-hedging strategy, and we actually successfully recovered a species that was on the federally endangered species list.

Living on Earth's host Steve Curwood speaks with Elizabeth Farnsworth with producer Lauren Hinkel. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: And that was?

FARNSWORTH: That was Robbins’ cinquefoil. It's a very diminutive little member of the rose family found only from a few populations on Mount Washington. So, in the alpine the main population was being completely destroyed by trampling.

CURWOOD: Hikers.

FARNSWORTH: Hikers, and we actually restored many, many plants in the population and actually started a new one close by, so the plant was delisted. It's the only one in the US that's ever been taken off the endangered species list. So the report spells out all of a lot of the hazards for New England's rare plants in particular, but there's also some good news in there. Plants are really very resilient and there are actually things that we can do individually and collectively to celebrate flora and to make it resilient for the future.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Farnsworth is a Senior Research Ecologist at the New England Wildflower Society. Thank you for taking the time with us today.

FARNSWORTH: Thank you so much. It was delightful talking with you.

Related links:

- New England Wild Flower Society’s “State of the Plants” report

- About the New England Wild Flower Society

- About Elizabeth Farnsworth

[MUSIC: Swing Gitan, “Manoir de mes reves,” The Spirit Of Django-The Django Reinhardt NY Festival, Recording Arts/Vertical Jazz]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, in the Bay area of Northern California, they’re considering taxing themselves to create buffers for climate related sea-level rise….

HILL: It's an accelerated problem. We have to work harder, we have to start sooner. We HAVE to do the things we can today, to be able to get ready for 4 to 6 feet.

CURWOOD: How they’ll do it, who’s complaining, and why. That’s next time, on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Margie Adam, “Naked Keys,” Naked Keys, Pleiades Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth