February 22, 2013

Air Date: February 22, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

National Parks on the Chopping Block

View the page for this story

Unless there's a last minute deal between Congress and the White House, draconian spending cuts will take effect across the federal government on March 1st. Joan Anzelmo, spokesperson for the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees, tells host Steve Curwood that the National Park Service’s already limited budget will be squeezed another 5% hit, causing delayed park openings and reduced staff. (05:30)

Secret Cash for Climate Denial

View the page for this story

There's broad scientific consensus that climate disruption is human-induced, yet global warming is still hotly debated. Suzanne Goldenberg joins host Steve Curwood to discuss her recent article in the UK newspaper The Guardian. It investigated the anonymosly funded Donor’s Trust and Donor’s Capital Fund which together have given over $100 million dollars to climate change denial groups in the United States over the past decade. (06:40)

Mexican Drug Gangs Turn To Coal Mining

View the page for this story

In Mexico drugs are an extremely lucrative business. But now at least one cartel, the Zetas Gang, is turning to coal mining instead. Journalist John Holman tells host Steve Curwood how coal can turn a profit for drug lords. (05:45)

Corn Ethanol Challenged

View the page for this story

Corn based ethanol makes up 10% of the fuel mix in the US and EPA has approved a 15% mix. But last year 20 ethanol producers closed up shop. Wallace Tyner, an energy economist at Purdue University explains to host Steve Curwood why small ethanol producers simply can’t turn a profit. (06:15)

Limpets and Cancer Vaccines

/ Lauren SommerView the page for this story

Researchers in Southern California are cultivating an unusual marine mollusk that could prove vital to the future of cancer vaccines. Lauren Sommer reports as part of the EYE-TRIPLE-E Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special, "The New Medicine: Hacking Our Biology". (08:00)

BirdNote® The Early Bird

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The proverb insists that the early bird gets the worm, but as Michael Stein explains in BirdNote®, feasting early might not be such a good deal. (01:55)

Pukka’s Promise to Live Longer

View the page for this story

Dogs have far shorter lives than many animals, including the humans that love them. From food to vaccines Ted Kerasote’s new book, Pukka’s Promise, examines how to help our dogs live longer. Ted Kerasote talks with host Steve Curwood. (13:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joan Anzelmo, Suzanne Goldenberg, John Holman, Wallace Tyner, Michael Stein, Ted Kerasote

REPORTERS: Lauren Sommer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Caught in the showdown between Congress and the White House over the budget-slashing sequestration cuts due on March 1st is access to America's iconic national parks.

ANZELMO: They tell our story as a country. They are interwoven into the entire heritage of all Americans. And I think we ought to channel our inner John Muir and make sure that we protect these incredible places and keep them for another 100 years of future generations.

CURWOOD: Also, a humble marine mollusk with a big medical future...

LINCICUM: So I’ll show you some of our up-and-coming limpets right here. So, if we take a look in this tank, these guys are fairly slow growing, but you can see them. These guys are about three and a half years old or so.

CURWOOD: The Keystone Limpet might be a key to new vaccines. That's this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

National Parks on the Chopping Block

Grand Canyon in Arizona is just one of the National Parks that will have to make difficult choices to shave its budget. (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

[RANGER: “Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park. This exceptional landscape has been home to people for the last 12,000 years. Join me, Ranger Brian, for a Ranger minute as we consider the lives of the ancestral Puebloans…”]

CURWOOD: But unless Congress and the White House can agree on a fiscal package by March 1, Ranger Brian and workers at Yosemite, Grand Teton, Yellowstone and hundreds of other national parks will have to delay opening and restrict hours. It’s all part of draconian spending cuts known as sequestration that would also slash military spending, education, and unemployment benefits. Joan Anzelmo is the former superintendent of Colorado National Monument and is now a spokesperson for the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees.

Visitors take in the view at Grand Canyon National Park. (Photo: National Park Service)

ANZELMO: The National Park Service has a relatively small budget of just $2 billion dollars annually to run 398 areas. And if sequestration goes through, the parks will have to cut a total of $110 million dollars on March 1, which is awfully late in the fiscal year to find those savings.

CURWOOD: So what would the parks have to do to save that amount of money?

ANZELMO: It's going to be a tough job. They will have to not hire seasonal park rangers and other employees. They will certainly have to reduce hours of operation at some locations reducing visitor center hours and other kinds of important services such as plowing the roads to get the parks ready to open.

CURWOOD: Well, talk to me about some specific parks and what you would expect to happen there. The Grand Canyon, for example.

ANZELMO: The Grand Canyon of course is one of the busiest national parks in the entire country and really in the world. And visitors are there right now, and many more visitors would want to be there in another month. And that's exactly when these cuts will kick in. And so some of the principal roads at Grand Canyon will be closed, and the main visitor center where everyone goes to get information to begin their hike and their experience will also have much reduced hours.

CURWOOD: What would happen with sequestration to our nation's very first National Park, Yellowstone?

Yellowstone National Park Sign (Photo: National Park Service)

ANZELMO: When Yellowstone opens for the spring season ,visitors begin to flow not only to Yellowstone National Park, but also to this entire region of United States. And Yellowstone, if you will, is the juggernaut of national parks in terms of international and national destination, but also it flows those economies - all those gateway communities from West Yellowstone, Montana, to Cody, Wyoming, to Jackson, Wyoming, to Red Lodge Montana - roads won't be plowed, openings will be delayed. All of the gateway communities and the entire economies of those states will be dramatically affected.

CURWOOD: So how important are our national parks in terms of the national economy?

ANZELMO: Parks are a huge economic driver for the country. The national parks contribute about $31 billion dollars annually to the economy and they account for about 250,000 private sector jobs.

CURWOOD: So another, in other words, trying to save $110 million could possibly affect billions?

ANZELMO: Exactly. I think we also should not lose sight of the early vision of why our country created these extraordinary places. This national park system that we have as Americans, thankfully the Congresses is in the late 1800s had far greater vision and recognize the importance of setting aside these extraordinary natural and historic resources for all future generations. And I fear if we were depending on the Congress of today there would be no Yellowstone, there would be no Grand Canyon, there would be no Cape Cod National Seashore right there in Massachusetts.

A ranger leads a group of hikers in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: The National Park Service budget has been tight for a long time and really, from the perspective of many, under budget. What would the sequestration due to the service itself?

ANZELMO: I think that the loss of employees, not hiring employees, is going to be a huge impact to the ability of the agency protect the resources, to serve the visitors, to respond to life-threatening emergencies whether someone becomes ill, or heaven forbid, they have a heart attack or an accident in the backcountry, in the mountains, on a remote lake. Or let's think about the wildfire season that is literally around the corner. The seasonal park rangers and seasonal employees of the National Park Service form a big part of the backbone of our federal firefighting infrastructure, and as you cut back on those numbers across the country, you cut back on our ability to respond to wildfires.

CURWOOD: Unthinkable, huh?

ANZELMO: It is unthinkable, and I think when we think about the national parks they tell our story as a country. They celebrate those victories, but they celebrate some of the shameful parts of our history. They are interwoven into the entire heritage of all Americans. And I think we ought to channel our inner John Muir and make sure that we protect these incredible places and keep them for another 100 years of future generations.

CURWOOD: Joan Anzelmo is the former superintendent of Colorado National Monument and now a spokesperson for the Coalition of National Park Service Retirees. Thank you so much.

ANZELMO: Thank you for calling.

Related links:

- National Park Service

- Coalition of National Park Service Retirees

Secret Cash for Climate Denial

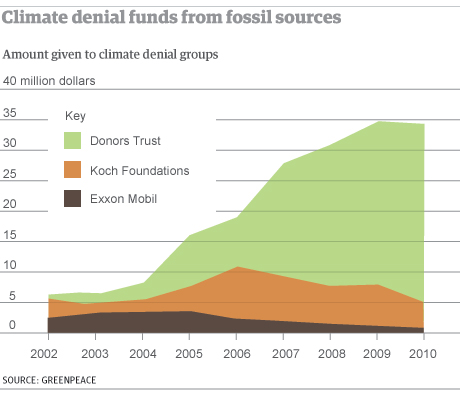

Graph of funding for climate denial from The Guardian (image: The Guardian)

CURWOOD: The 2012 US presidential election was the most expensive in history, and much of the six billion dollars spent came from undisclosed donors. There's no question that secret money is powerful and influential in American public life - and not just on electoral races. A recent investigation by the UK newspaper, The Guardian, revealed that over the past decade a pair of anonymous donor funds gave over $100 million dollars to US groups that deny a human role in climate change. Suzanne Goldenberg, the US environment correspondent for The Guardian conducted the probe, and she joins us now.

GOLDENBERG: Donors Trust and Donor's Capital Fund are two vehicles which were put together for the express purpose of channeling donations from conservative donors to conservative groups. They have tax advantages for wealthy donors, but the other thing they offer their clients is an assurance the money won't be diverted to liberal causes, and complete anonymity. So they don't have to become known as the benefactors of these causes.

CURWOOD: How much money we talking about here?

Suzanne Goldenberg (Photo: Suzanne Goldenberg)

GOLDENBERG: Over the last 10 years or so they've raised about $400 million dollars, of which about a quarter, a little more than $100 million dollars has gone to about 100 different organizations that have worked to undermine the science behind climate change, or have worked to block action on climate change.

CURWOOD: Now, how does this work in US law if these are a tax-exempt organizations, one would think they would have to reveal their donors.

GOLDENBERG: No, these are perfectly legal. As conservatives point out there's an equivalent on the liberal side of the political spectrum called the Tides Foundations. These things are perfectly legal, and what they do is they enable people to give money to a sort of black box, if you like, a council of advisors who will then distribute the money to other causes. So you can see the money going out to those causes, but you can't see the money going in.

CURWOOD: Suzanne, who are the groups who are getting these funds?

GOLDENBERG: You're talking about a range of groups here. You're talking about think tanks, organizations like the Heartland Institute in Chicago which over the years has organized annual conferences which are kind of an alternative to the UN climate conference where gather scientists and academics who do not accept established science on climate change. You’ve had other organizations which have focused on bringing lawsuits against climate scientists. One of the group they support is called Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow, One of its main causes is to put out a website called Climate Depot, which is a clearinghouse of information that attacks the science behind climate change and attacks people trying to bring about action on climate change. It’s published, for example, the phone numbers of climate scientists and the e-mail address of climate scientists and encouraged people to write angry e-mails to these people. So it’s a range of organizations that are supported by Donor’s Capital Fund and the Donor’s Trust.

CURWOOD: So let’s step back for a moment. This is a dark pool. We don't know where this money is coming from. But the folks who stand to perhaps lose the most if this country takes on the challenge of climate are those who are in the fossil fuel industry.

GOLDENBERG: That's true, I mean, economically, but I don't think you can say that this is just about the money I mean, the more I’ve studied these groups - and I’ve studied for long time - I think you cannot ignore the importance of ideology here. A lot of wealthy conservatives who are opposed to action on climate change, not because all their money is wrapped up an oil companies, but because they really are opposed any kind of government intervention in the economy. And they are afraid that if you start to put limits on carbon emissions and that's the sort of first step towards lots of government intervention in the economy, and then next thing you know we’ve got a global government and a single global currency.

CURWOOD: Conservatives aren’t the only ones that use anonymous donor mechanisms; liberals do as well. What's, what's the problem here?

GOLDENBERG: To me that the main difference is the causes they’re supporting. When you're talking about science - when you're talking about the facts of climate science - the two sides aren't equivalent. And I don't think that it's legitimate to say putting out information about science is one thing and putting out information that is factually wrong is just as valid. Because they clearly aren’t. I think as a society we’d be concerned if organizations were taking secret money to go out and say, hey, smoke as many cigarettes as you like, it won't hurt you; hey, be afraid when you use a public washroom, you can get HIV aids from toilet seats. I think it's a very different thing when you're talking about putting out information that is factually incorrect, and you're doing that in a secretive fashion.

CURWOOD: So how are these groups involved in the public discussion on climate? I'm thinking of President Obama recently saying in his State of Union as well as his inaugural address, that he wanted to be more active on that. Donor’s Trust supported organizations in response to that?

GOLDENBERG: They jumped right on it. It was really interesting to see. You know, the folks at Climate Depot put out a point by point rebuttal of the things that Obama was discussing in his State of the Union address. And since then, it’s also interesting to see Climate Depot have really gone on the attack against the protestors of the Keystone Pipeline project.

CURWOOD: Suzanne Goldenberg, you’ve been looking at this now for more than a year. What effect do you think that the Donor’s Trust and the Donor’s Capital Fund has had on the climate conversation in this country over the past few years?

GOLDENBERG: I think they’ve created a lot of confusion, and a lot of controversy about an area that used to be seen as apolitical, and with the solutions used to be seen as clear-cut. So they have made it virtually impossible for the White House or for the Congress to act on climate change because this area is now seen as so...you know it's a political third rail, if you like. And they have scared the politicians away from taking on a big challenge.

CURWOOD: Suzanne Goldenberg, is the US environment correspondent for the UK paper, The Guardian. Thank you so much Suzanne.

GOLDENBERG: Thank you.

CURWOOD: We asked Donor's Trust for comment. An email from CEO Whitney Ball is on our website, loe.org, and it reads, in part, "Donor’s Trust was established to promote liberty and to help like-minded donors preserve their charitable intent. As donor-advised funds are not required to disclose their donors,” she wrote that “comments in the press that label the Trust as ‘secretive’ and refer to its ‘dark money’ are ‘unfair and misleading’.”

[Donor’s Trust full statement on 2.22.2013:

“Donors Trust was established to promote liberty and help like-minded donors preserve their charitable intent. We follow the same rules and operate in the same manner as other donor-advised funds which include the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund, Jewish federations, local community foundations, and the left-of-center Tides Foundation, just to name a few. Donor-advised funds are classified as public charities, and thus are not required to disclose their donors. I do not know of a donor-advised fund that makes its donor list public. The press has referred to us as a "black box," labeled our funding as "dark money," and Ms. Goldenberg described us as "secretive." These characterizations are unfair and misleading. How is it that the Tides Foundation, which has a record of funding environmental causes and does not publish its donor list, is never characterized in the same way by these same reporters?”]

Related links:

- Original Guardian article

- Suzanne Goldenberg’s staff page

- Donor’s Trust webpage

[MUSIC: Nina Simone “Jelly Roll” from here Comes The Sun (Sony Music 1971) Happy Birthday Nina Simone 2/21/1933 – 4/21/2003]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tadd Dameron w/ John Coltrane: “On A Mistty Night” from Mating Call (Prestige Records 1956) Happy Birthday Tadd Dameron (February 21 1917 – March 8, 1965)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...drug gangs in Mexico turn to the earth for a new source of income. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Mexican Drug Gangs Turn To Coal Mining

For some gangs in Mexico, mining coal can be more profitable than selling drugs. (Photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Illicit drugs are a wildly lucrative business for many gangs in Mexico. But at least one cartel, the Zetas Gang, has found something even more profitable - coal mining. The state of Coahuila borders Texas and produces 95 percent of Mexico’s coal. It’s also ground zero for Mexican drug cartels turned coal barons. That’s according to a recent article in Al Jazeera, written by reporter John Holman, who joins us by phone from the roadside in Mexico. John, Welcome to Living on Earth.

HOLMAN: Hello!

CURWOOD: So how is it possible that mining for coal can be more profitable than selling illegal drugs?

HOLMAN: Well one of the big things is that in Coahuila there lots of small clandestine mines called pothos. And these sorts of mines that have very little regulation - and so obviously they can have bigger turnover from gangs like the Zetas gang - and obviously miners in that state not usually very highly trained and poorly paid - so that’s another reason they could earn a lot of money from it.

CURWOOD: So these are small little clandestine mines on the side of the roads that people are working.

HOLMAN: Yes, obviously Coahuila also has its share of bigger mines; as you said, it’s responsible for 95 percent of Mexico’s coal output. These small mines as you drive through Coahuila - as I did - and you can see them on the side of the roads in the coal district. And they’re literally just some men gathered around what looks a very ropey sort of machine to lower them down into the depths of the earth and bring up that coal.

CURWOOD: So walk me through this process. Who buys this coal from the drug cartels?

HOLMAN: It’s a process going first of all from these smaller mines, then larger established companies, it’s been alleged by this coal, and then they in turn send it on to a state company called Prodemi who sells it to all sorts of people, including Mexico’s nationalized electricity board. So this is why this has blown up to be quite a scandal in Mexico because amongst the companies that end up with this coal as well as private companies are state-run companies.

CURWOOD: So how right am I to assume this is a dangerous business? And how have the legal coalminers reacted to the drug cartels getting involved in the coal mining business?

HOLMAN: Well to give you an idea, the weekend, we went down to investigate this. I think a day or two before a miner had been killed and tortured, it seemed, because he talked about what was going on. The ex-governor’s son was killed, there’s a lot of police, a lot of navy, a lot of army in Coahilla at the moment; the state’s very much on edge.

CURWOOD: How has this evolved with the drug war down there? I know that the leader of the Zeta’s gang was killed by Mexican federal government, the navy I believe.

HOLMAN: Yes. You’re exactly right. He was actually killed in a village called Progreso, known as a coal mining village. And from that people have inferred the link between him and mining, and several people have said that saying he was sort of making the change to becoming a miner from being a drug baron. But this state is very much in the hands of the Zeta gang, one of Mexico’s most ruthless drug gangs, among them showing a certain talent in expanding into other businesses - extortion, people trafficking, pirate copies of DVDs and things like this - and it seems like this is the latest venture for them.

CURWOOD: How safe is it for you to operate there as a journalist?

The state of Coahuila borders Texas and produces 95% of Mexico’s coal. (Image: Google Maps)

HOLMAN: In Coahilla I think it’s very difficult. The local journalists that we’ve talked to say there’s certainly a lot of subjects they can’t write about. One of the journalists we were wandering around with told us some things that seemed quite incredible, and said that he couldn’t report it in his local paper because if he did, then the likelihood is that he would end up dead.

CURWOOD: So what kind of things did he say?

HOLMAN: The story is just coming out now about villages in the state which...they’re basically ghost villages due to huge or just mass killings. And these stories are really just coming out now. Mostly of the national magazines or international media that come in and go out. As I said for the local reporters the it’s very dangerous to talk about these things.

CURWOOD: Now what about the safety of coal miners and the environment for that matter?

HOLMAN: The safety of coal mining in that region has never seemed to be a priority concern about operating the mines. Almost seven years ago, there was huge accident – in which 65 miners died - and some of those bodies have never been recovered. And mining advocates there for miners’ rights say the situation hasn’t improved that much, and even with the acquisition of the mines by organized crime. It’s probably going to get a little worse for them because a few safety regulations that legal mines needed to uphold have now been sort of stripped away. So I would say in summary sort of not too good and probably getting worse for the miners.

CURWOOD: And how about the environment there?

HOLMAN: Many mines have got a lot of regulation and that’s sort of on track with the federal government. But again, if you’ve got these artisanal these small-scale mines that are being run by groups that aren’t beholden to the law in any way, then that sort of thing isn’t going to be great thing for the environment. The only thing is that most of these mines are very small scale. So the impact for those small-scale mines wouldn’t as bad for the environment.

CURWOOD: So, John Holman, what’s next, now that the government knows that organized crime is involved in coal mining and they’ve killed the leader of the Zetas gang? What are they going to do about it?

HOLMAN: Well at the moment there’s a federal lawsuit investigation ongoing; they have sent a lot of federal investigators, I believe about 200, into the state to see what’s going on there. But as yet there’s been no dramatic conclusion or mass arrests.

CURWOOD: Reporter John Holman speaking to us from Mexico. Thank you so much, Sir.

HOLMAN: Thank you.

Related link:

Al Jazeera article

Corn Ethanol Challenged

The vast majority of domestic ethanol in the US comes from corn. (Photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: The current gasoline we put in our cars - E10 - contains 10 percent ethanol. Corn-based ethanol helps provide income for American farmers, and a federal mandate for ethanol aims to reduce global warming emissions. In 2012, the EPA ruled that it would be safe for cars made since 2001 to use a fuel containing 15 percent ethanol. But an ethanol tax credit expired over a year ago, and more than 20 ethanol plants have closed in the last year. Wallace Tyner is an energy economist at Purdue University and Professor Tyner, welcome to Living on Earth.

TYNER: Steve, it's great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So 20 ethanol plants closed up shop last year. Why?

TYNER: Well basically because there's too much ethanol chasing too little market in the United States. The reason for that is because we have something called the “blend wall”. We consume about 133 billion gallons of gasoline-type fuel a year, and that means blending at 10 percent, or 13.3 billion gallons, is all we can use; but we have the capacity to produce 14.9 billion gallons. So we have more capacity than we can sell ethanol, and that means that everybody can't stay in the game.

CURWOOD: And what about drought...how has that affected the ethanol business?

(Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

TYNER: Instead of being priced on gasoline is it used to be, today ethanol’s priced on corn so when we had the drought, that meant that the price of corn went up significantly, but also the price of ethanol went up significantly. And what happens is that ethanol gets priced on a break even basis with corn, but that’s break even for the efficient producer. For those that are somewhat less efficient, they have a really hard time. Some are losing money, some are suspending production, some have gone bankrupt. It is really tough to make money in ethanol today.

CURWOOD: So the market for corn-based ethanol here in the United States is set by the EPA, in the renewable fuels standard, this blend of 10 percent. But I understand that of course in Minnesota they are authorized to go to 20 percent. And there’s been talk of raising the federal level to 15 percent. And yet get some say, “no no no, that's too much, it should be less”. What’s your opinion?

TYNER: Well, Steve, in fact, 15 percent has been the rule for a year now. EPA gave their final clearance for 15 percent ethanol in February of last year, but the way they cleared it they said we're going to allow E15, that's what it's called, for cars built since 2001, but not for any small engines, not for motorcycles, not for chainsaws snow blowers, lawnmowers boats, etc. And the cars built since 2001 is about two-thirds of the car fleet. So put yourself in the position of a service station owner - are you going to switch from E-10 to E15 and lose a third of your customers...and also have to police to make sure that nobody takes any gas away in a can that they’re going to use in any of those small engines? So we have 161,000 gas stations in the country and only 10 of them have switched to E15.

CURWOOD: Now some 40 percent of the corn that we grow the US is converted into ethanol, do I have that right?

TYNER: 40 percent of the corn that’s produced goes into ethanol plants. But a third of that comes back out as distillers’ grains that feed straight to animals just like the corn would've been. So the net number is about 27 percent of our corn gets used for ethanol instead of being used to feed people and animals.

CURWOOD: And how does that compared to exports to other countries?

TYNER: We’re the world's leading producer of corn ethanol by a long shot. The second largest producer of ethanol is Brazil, but they produce it from sugarcane.

CURWOOD: How does corn rate as a biofuel compared to sugarcane?

(Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

TYNER:The ethanol that’s produced from corn is identical chemically in every other way with the ethanol produced from sugarcane. And ethanol produced from corn has been rated by EPA to reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to gasoline by about 23 percent, but the EPA's also said that sugarcane ethanol reduces greenhouse gases around 50 percent. So in terms of achieving the objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, sugarcane, according to EPA does a better job. But they both do reduce, according to EPA, greenhouse gas emissions.

CURWOOD: Now, you're the economist. Do you have a sense of how much the price of corn is going up because we’re putting so much of it into ethanol?

TYNER: There is no doubt that biofuels are an important contributor to the rise of corn price but it's not the only contributor. We have higher demand in developing countries as their incomes are growing and their diets are switching to more meat in the diet. That means they need more corn to feed more animals so there are whole lot of drivers of the higher corn price. Biofuels is one of those. It's an important one, but people that say it's the only driver - no, it's not.

CURWOOD: What about the demand for land to grow corn and the biofuel that comes out of it? The Environmental Working Group, for example, claims that the increase in the price of corn for ethanol has lead to the conversion of some 23 million acres of wetlands and grasslands, an area roughly the size of your state there in Purdue, Indiana.

TYNER: Well, that's a great question because when you take corn away from feeding animals, which is what most of its used for, and divert it to producing ethanol, those animals still have to be fed. So you can get that extra land two ways, one is you get it from crop switching, and that's what we're done in United States - were growing less cotton, less sorghum, a little bit less wheat, and we're growing more corn. And so we’ve shifted the mix of acres around the country. In other parts of the world - in sub-Saharan Africa, in South America, in Brazil, in Eastern Europe - cropland area has increased in all those regions. And part of that is because the world price of corn, the world price of soybeans, are higher and so farmers in those regions are expanding area.

CURWOOD: Wallace Tyner is an energy economist at Purdue University. Thank you so much, Professor Tyner.

TYNER: Anytime, Steve.

Related links:

- Wallace Tyner’s web page at Purdue

- EPA’s E15 decision

- Biofuels Digest

[MUSIC: Various Artists/Nina Simone “Here Comes The Sun” from Remixed And Reimagined (BMG Records)]

Limpets and Cancer Vaccines

California limpets (photo: Spectrum Magazine)

CURWOOD: Think medical breakthrough, and you're apt to picture a high-tech lab with gleaming steel equipment. But medical advances can also come from nature, such as the seaside. In Southern California, researchers have found a way to grow an unusual marine mollusk that may play a major role in the future vaccines. Lauren Sommer went to explore this unique laboratory site - her story comes to us from the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special, "The New Medicine: Hacking Our Biology."

[OCEAN WAVES]

SOMMER: When you think of cancer treatment, this probably isn’t the scene you’d imagine. But this rocky strip of land in Port Hueneme in Southern California is home to a unique medical facility.

LINCICUM: So, what you’re seeing right now is - this is our primary production seawater system. Essentially, we pump nutrient-rich seawater right over here from the port. We really just remove big particulate matter before it flows into our production tanks.

SOMMER: Brandon Lincicum is the aquaculture manager for Stellar Biotechnologies. We’re standing next to large tanks just a stone’s throw from the Pacific Ocean.

LINCICUM: Take a look at some of these guys. OK, so, this is what you’ve been waiting to see. This is Megathura crenulata right here, the giant keyhole limpet.

SOMMER: Lincicum reaches into the tank and pulls out a round, purplish animal that looks like an abalone.

LINCICUM: They do have a hard shell, but they have this mantle tissue that they can fold up over their shell so you know, when you touch these guys, they are almost soft. It’s almost...

SOMMER: A little slimy.

LINCICUM: A little slimy? Right? A little bit.

SOMMER: The limpet he’s holding weighs almost a pound, but it takes years for them to grow this large.

LINCICUM: So I’ll show you some of our up-and-coming limpets right here. So, if we take a look in this tank, these are our limpets, and these guys are fairly slow growing, but you can see them. These guys are about three and a half years old or so. We produce these guys from sperm and egg—microscopic sperm and egg. These guys are teeny tiny.

SOMMER: This is the only place in the world where giant keyhole limpets are bred and grown. And there are thousands here, each with their own unique tracking number. The question is, why?

OAKES: It pretty much is a nondescript member of the local California coastal environment but turns out to be really important when it comes to medical technology.

SOMMER: Frank Oakes is the CEO of Stellar Biotechnologies. He says what’s special about giant keyhole limpets is their blood—or more specifically, something found in their blood called KLH.

OAKES: Keyhole limpet hemocyanin. And then, hemocyanin is the protein from the blood, analogous to hemoglobin in humans.

SOMMER: This unique blood protein, KLH, has been studied since the 1950s, and it’s played a major role in immune system research. But the keyhole limpet is only found in Southern California, which means there’s a limited supply.

OAKES: It was harvested routinely for extraction of its blood, and with little regard to understanding the animal, its importance in the wild, or the perishability of the wild population.

SOMMER: Oakes has a background in aquaculture, so he began studying how to breed limpets in captivity.

OAKES: In the late 1990s, we started work on developing nonlethal extraction methods for the animal, so we can take the blood without killing them.

SOMMER: Getting limpets to grow in captivity was no easy task. Oakes had to learn how to coax them into reproducing. He had to learn what conditions they grow best in. And because the limpets are part of medical research, there has to be strict quality control to prevent contamination. Today, thousands of limpets go through their entire life cycle in a controlled system, giving blood several times a year.

OAKES: From a 50-animal lot, we get about a liter of serum. And from that liter of serum, we will typically produce about 20 grams of protein. And at retail value, that 20 grams of protein for us is approximately $100,000.

SOMMER: Why would a blood protein be so valuable?

CHOW: Without it, a lot of the vaccines will not work.

SOMMER: Herb Chow is a vice president at Stellar Biotechnologies. He says to understand why KLH is useful, you have to go back to the early days of vaccines. Medical researchers would take something harmful like a virus, kill it, and then inject it into your body. Your immune system would see the inactive virus and it would learn how to attack it.

CHOW: Except if you use the dead virus or dead bacteria, it does accomplish that activation or stimulation, but it comes with a price. The price is some level of toxicities: People get sick because the toxin is still there.

SOMMER: So researchers took viruses apart, pulling off the small chunks that your immune system could attack. They injected those smaller pieces as the vaccine, but there was a problem.

CHOW: Just too small. They don’t see it. So it becomes stealth to your immune system.

SOMMER: And like a stealth plane, if your body doesn’t see it, it can’t learn to attack it. But attach those virus pieces to KLH, and it’s like attaching reflectors to the plane.

CHOW: By putting two together, all of a sudden the radar starts seeing it.

SOMMER: And your immune system mounts an attack or starts making antibodies. KLH itself is neutral and doesn’t harm you. Chow says it’s being used in vaccine research for Alzheimer’s and autoimmune diseases. It’s also being used in cancer vaccine research.

CHOW: The problem with the cancer cells is a lot of the antigen that are expressed on the cancers is actually your own tissues. The body sees them: This is my own, I shouldn’t react to it.

SOMMER: Cancer cells are, in essence, your own cells. So your immune system doesn’t see them as foreign invaders.

CHOW: And, as such, it fools your immune system to kind of ignore them and let them keep growing. And when the tumor mass gets to be a certain size, then your body no longer be able to handle it.

SOMMER: So doctors use treatments like radiation and chemotherapy, which target all fast-growing cells in your body. But Chow says that’s why cancer vaccines have such promise.

CHOW: It’s something that it’s high on the radar screen because of the characteristics - that they can differentiate the normal cells from the tumor cells and be able to target the treatments to the tumors.

SOMMER: Cancer vaccines could train your body to only attack the cancer cells. Chow says the challenge is finding something on cancer cells that would help your immune system differentiate them from your own cells.

CHOW: And there are differences, and it used to be we are looking at differences on the cell surface, and it seems like that difference is not big enough. There are some differences, now we’re going inside the cells, looking a lot - zillions of molecules inside the cells - and you find more differences.

SOMMER: Today, most of the cancer vaccines that use KLH are still in the research phase or in clinical trials. But CEO Frank Oakes says the role of KLH is looking promising.

OAKES: The long-term commercial demand for KLH looks very promising because it’s a key ingredient in a wide variety of drugs that are currently in clinical development.

SOMMER: The challenge is that vaccines take decades to develop - and not all of them come to market.

OAKES: Unfortunately, in this business, more drugs fail in clinical development than succeed.

SOMMER: But Oakes says with the growth in cancer vaccine research, there’s a good chance that this mollusk from Southern California will eventually play a role in keeping us healthy. In Point Hueneme, I’m Lauren Sommer.

CURWOOD: Lauren's story on the Keyhole Limpet comes from the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special, "The New Medicine: Hacking Our Biology".

Related links:

- Spectrum website

- Stellar Biotechnologies website

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Hold On” from All We Are Saying (Nonesuch Records 2011)}

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tadd Dameron: “Fontainbleau” from The Compositions Of Tadd Dameron (Riverside records/Verve Music Group 2011)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...Nosing out a path to longer life for our best friends. That's just ahead on here on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[BIRD NOTE THEME]

BirdNote® The Early Bird

American Robin with insect (photo: Tom Grey

CURWOOD: Here at Living on Earth, we occasionally encounter evidence that a familiar proverb may, in fact, not be true. And in BirdNote® today, Michael Stein reveals one adage that seems to miss the mark.

American Robin singing (photo: Tom Grey)

[AMERICAN ROBIN SINGING]

STEIN: We’ve all heard about the “early bird” getting the “worm.” We know it as sound advice about initiative and timely action. And we can almost see that robin leaning back and tugging that recalcitrant worm out of the ground.

[COMICAL SOUND OF PULLING AND STRAINING WITH A “POP” AT THE END]

STEIN: Research shows, however, that birds dining early and heavily may lower their life expectancy. A study of three North American woodland bird species found that socially dominant birds stay lean during the day and then stoke up when it’s most important - later in the day, before a cold night. At night, birds avoid hypothermia by metabolizing fat. And by staying lean through most of the day, dominant birds are more agile in avoiding predators.

American Robin with worm (photo: Tom Munson)

Subordinate birds have to look for food whenever and wherever they can find it, and carry fat on their bodies to hedge against unpredictable rations. Dominant birds, which can push subordinates off food, can choose when they eat and so lessen their odds of being eaten themselves.

[AMERICAN ROBIN SONG]

Therefore, at least in the woodland bird’s world, the revised moral might read: “Get the worm late in the day - you’ll sleep better and live longer.”

[AMERICAN ROBIN SONG]

I’m Michael Stein.

[Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of the American Robin provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by W.L. Hershberger

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

Narrator: Michael Stein]

Related link:

Story on Birdnote® website

Pukka’s Promise to Live Longer

Pukka in the Grand Tetons of Wyoming. (Photo: Ted Kerasote)

CURWOOD: Dogs have shared our lives and our homes for thousands of years. They are our best friends, and we give them our hearts knowing that we'll most likely outlive them. Some very small breeds can live up to 20 years, but most dogs only make it half that far. Bestselling author Ted Kerasote, mourning the death of his beloved dog Merle, decided to find out how to help dogs live longer. The result is his new book Pukka's Promise, named for his new dog Pukka, but the inspiration came while he was on the road promoting his previous book about Merle.

KERASOTE: It was in Monroe, Louisiana, there in the deep south...I was checking my e-mail before doing my evening presentation and once again was struck by this common refrain that I had been seeing in hundreds of emails. “Why did my dog die at two-years-old, three, four? Why did four out of five of my golden retrievers die of cancer?” I sat back and thought, “why do our dogs die so young? Merle himself, why did he die at 14 when some of my horses are still going strong today at 25?” So I started doing some research and discovered that dogs are a short-lived species relative to some other animals because they’re direct descendants of wolves - sharing 99.9% of their DNA. And wolves themselves are a short-lived species. So our dogs have inherited this fateful genetic legacy. But how we raise and breed them can further shorten their naturally brief lives.

CURWOOD: You found Merle wandering in the desert. He was a stray, but for your new puppy, Pukka,you went to a breeder. Why a breeder?

KERASOTE: After Merle died, I didn't want another dog right away. I needed to let my heart heal. I wanted to write his biography without another dog deluding my memories of him. So I spent three years doing that, then I started looking for another dog. I went to shelters first, but I simply didn't find a dog in a shelter with whom I fell in love the way I had fallen in love with Merle almost on the spot. And I wanted some certain qualities in a dog: I wanted him to be able to be out in cold weather, to ski, to swim rivers, to mountain bike with me.

Ted and Pukka skiing. (Photo: Ted Kerasote)

CURWOOD: Now wait a second, a dog skis...

KERASOTE: I'm using that term poetically. Running behind one as one skis downhill, the dogs either porpoise through the snow if it’s shallow enough or swim through it if it’s steep and light enough.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] OK.

KERASOTE: So I wanted a dog with similar qualities to Merle, and finally decided that maybe I could find such dog by going to a breeder, and that it would also be instructive for researching and writing the book...to describe to people how they could hedge their bets about getting a healthier longer lived dog like going to a reputable breeder that had done all the appropriate orthopedic health screenings and DNA tests for that breed.

Pukka relaxing (Photo: Ted Kerasote)

CURWOOD: One advantage of going to a breeder to get a dog is that the dog won't be spayed or neutered. And almost inevitably from a shelter dogs have been sterilized.

KERASOTE: Correct. Correct.

CURWOOD: So why did you want a dog that would be able to reproduce?

KERASOTE: I had been reading the veterinary literature, and there’s been emerging evidence over the last decade that spayed and neutered dogs are not as healthy or longer lived as intact ones. Spayed and neutered dogs have a greater chance of having an adverse reaction to vaccines, in general they are more obese. They have more endocrine dysfunction. Pretty serious stuff. And Intact dogs tend not to have those conditions as often, and they tend to live little bit longer. In addition, we now have procedures that can forestall a dog’s having puppies, but that keep a dog’s beneficial sex hormones there - tubal ligation, hysterectomy or vasectomy - the same procedures used in human medicine. However, they don't touch a dog’s testes or ovaries so that a dog retains its beneficial sex hormones, estrogen and testosterone, which have been shown to forestall or prevent many of those nasty conditions I just mentioned.

CURWOOD: Now, there's another controversial topic you take up in your book, and that's whether not to vaccinate dogs, or perhaps I should say vaccinate dogs as much as they are vaccinated. You did a lot of research on this topic. Tell us what you found.

KERASOTE: Vaccines, for all the good they do, are not benign. They can cause adverse reactions, everything from welts to arthritis to fatal hemolytic anemia. And it has been found now that the duration of immunity for the core canine vaccines, parvovirus distemper, adenovirus 2...and rabies is far longer than any of us have imagined. It actually seven to 15 years, yet some veterinarians continue to recommend annual vaccinations for our dogs, overloading their immune systems. However, some vets say instead of vaccinating your dog, have your vet give it a blood test called a Titer. The Titer measures the antibodies that the dog has developed to these diseases. If the dog has immunity, no need to re-vaccinate it at three years. If it's lost its immunity, give it a booster shot.

CURWOOD: How common is it to test for the Titer for antibodies?

KERASOTE: Now that has become pretty common, unlike tubal ligations and vasectomies. There are labs around the country that your vet can send a blood sample to, and a couple weeks later you get the results back.

CURWOOD: So in the modern world we live in, there are a lot of chemicals, and dogs perhaps are exposed more to these chemicals than we people are. Can you talk about that?

KERASOTE: You bet. Dogs are smaller than adult humans, and just like small children they receive a greater dosage of the environmental toxins around us per unit of body weight than do we. Dogs also are on the ground. They live on ground. They take in the world through their noses so they're breathing in chemicals that we don't breathe in. They also walk around bare-pawed on city streets, and on lawns that have been sprayed with herbicides. And when they get home at night, they don’t take a shower, as do we. They lick their paws, they lick their fur, further ingesting these chemicals.

Ted and Pukka out on a hike. (Photo: Ted Kerasote)

CURWOOD: Let me talk to you about breeding dogs. You say that dogs are inbred overly in this country, and that that's part of the mortality problem, or the disease problem for dogs. Can you explain?

KERASOTE: Yes fewer and fewer sires are being used. One of the best examples is the golden retriever. Back in the 1970s, three famous sires contributed enormously to the gene pool, so today they have about two to 300,000 descendants. What happens when you have those many descendants then breeding is you have the possibility, a much greater possibility, of recessive genes meeting. And recessive genes can cause anything from something nice like a coat color - the yellow lab, two recessive genes - but they can also cause blindness, muscle wasting disease, they can cause exercise-induced collapse and they can cause cancer. People think, experts feel, that one of the reasons that so many dogs are dying of cancer purebred dogs is that there were too many of these fatal recessive genes floating around and now meeting.

CURWOOD: I have to say that your book is a pretty personal one for me. We recently lost our family dog, Mr. Crumpett, a golden retriever to cancer...

Golden Retriever, Mr. Crumpett (Photo: Steve Curwood)

KERASOTE: Oh dear.

CURWOOD: And a few years earlier lost Zoe, also a Golden Retriever to cancer.

KERASOTE: How old were they?

CURWOOD: About nine each. This inbreeding perhaps might have promoted the odds of cancer?

KERASOTE: Absolutely, because your dogs are more than likely related to those three popular sires whom I mentioned back in the 1970s.

CURWOOD: All this talk about inbreeding...I would think that that would make the case for getting a mixed breed dog. Those dogs that perhaps could be saved from a shelter, for example.

KERASOTE: Absolutely, and if we look at the veterinary literature it shows that mixed breed dogs live about 1.8 years longer than an equivalently weighted purebred dog. And they also have fewer genetically transmitted diseases.

CURWOOD: So given this cancer epidemic, what should people do?

KERASOTE: As soon as they see a bump, a little bump on their dog, they should not hesitate. They should go to their vet and say, “what is going on?” I visited four major oncology centers around the country. They saw far too many dogs six months after having been to a general practitioner veterinarian who said, “let's just watch this,” and they now had to amputate the dog’s leg or give it chemotherapy whereas six months before it would have been a small tiny incision.

One of the oncologists at CSU said to me, “What are the four most dangerous words in the English language? Let's...just...watch...it.”

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about dog food. In your book, I counted them up, you got four chapters just on food.

KERASOTE: We all love to eat.

CURWOOD: And so do dogs. And I would guess that most Americans feed their dogs bags of kibble or perhaps canned food, but you found that that is not the best way to go. Can you explain?

KERASOTE: Yes. Most of moderately priced kibble is made from corn. Well, there are lots of problems with corn. Corn is one of the most heavily sprayed agricultural crops in North America; it receives 30 percent of the pesticides put on our crops. These days, 85 percent of the corn crop is also genetically modified, which means that it's repeatedly sprayed with the herbicide Roundup. So one might say, you know, maybe we shouldn't feed our dogs high carb diets. On the other hand, vegetables green leafy vegetables, yellow-orange vegetables have been shown to be cancer protective whether you’re a dog or a human. And another group of interesting studies show that when dogs eat a high-protein diet, their performance improves. They have a higher VO2 max, more endurance, they’re aerobically fitter, and they have better thermoregulation.

CURWOOD: So you're not that suggesting people do what you do there in the Grand Tetons of Wyoming with your dog Pukka, and that is you get the rifle and you go out get yourself an elk.

KERASOTE: I do get an elk. Of all of the meats I tested in foods, the elk had the fewest amount of heavy metals, lives far from roads, far from industry, but I can’t feed Pukka on wild game. I couldn't shoot enough big animals for Pukka to eat, so Pukka eats a commercial frozen raw food diet; he eats kibbles that meet the criteria that I just suggested, and I rotate him through a variety of foods.

CURWOOD: What about beef?

KERASOTE: I don't feed Pukka beef.

CURWOOD: Why?

KERASOTE: Ecologically it's better to eat wild grazers or grass fed beef, nor do I think corn fed beef is as healthy as some of the other meats I feed it Pukka. It's shot up with antibiotics with hormones, it lives on a feedlot and eats corn - and we’ve talked about the problems that corn has.

CURWOOD: Ted Kerasote, if you had one piece of advice for a dog owner, what would that be?

Ted Kerasote and Pukka. (Photo: Ted Kerasote)

KERASOTE: To have more of an ongoing conversation with your dog. Get down on the ground with your dog in your house. Try to understand what it's telling you more about what it wants, how often it wants to go out, where it wants to go instead of always deciding that you're going to take it someplace - let the dog decide to tell you where it's going to take you for the walk that day.

CURWOOD: Do the dogs keep us...or do we keep the dogs?

KERASOTE: I think it's mutual. We have this on going conversation with each other and if we're doing it really well we try to meet each other’s needs.

CURWOOD: Ted Kerasote's latest book is “Pukka's Promise, the Quest for Longer Lived Dogs”.

Related link:

Ted Kerasote’s website

[MUSIC: Jason Moran “Journey Up River (Hagar’s Suite) from Hagar’s Suite (ECM Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. And we wish a fond farewell to Annie Sneed as she sets off traveling. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and check out our Facebook page. It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic. com. Support also comes from you our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at PaxWorld.com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth