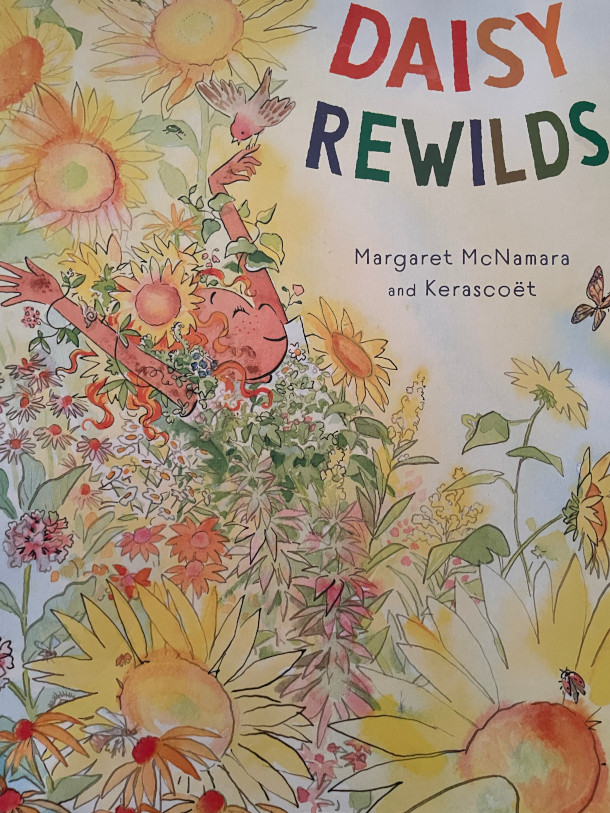

Daisy Rewilds

Air Date: Week of February 13, 2026

Daisy Rewilds, published in 2025 by Penguin Random House, follows a young girl’s journey reverting her own front yard to its natural state. (Photo: Taken by Andrew Skerrit, Book Cover via Penguin Random House)

The young hero of children’s book Daisy Rewilds not only likes nature, but she also wants to become nature. Daisy refuses to take baths and reverts the manicured lawn of her family home back into the wild, all with a bit of hilarity. Weeds and worms show her family and neighbors the true beauty in nature, chaotic as it can be. Daisy Rewilds author Margaret McNamara joins Host Steve Curwood to share how the concept of rewilding or allowing outdoor spaces to revert to more natural states, inspired this whimsical tale.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Many, perhaps most young children love nature and being outside, if given the chance to stomp in a mud puddle or try to catch a frog or a butterfly. And then there is the story of Daisy, a most intense third grade nature girl, the hero in a fable created by author Margaret McNamara. Daisy not only likes nature, she wants to become nature. She refuses to take baths and reverts the manicured lawn of her family home back into the wild, all with a bit of hilarity. Weeds and worms show her family and neighbors the true beauty in nature, chaotic as it can be. Daisy Rewilds by Margaret McNamara is the latest of her three dozen books for young readers, and it was inspired by the concept of rewilding, or allowing outdoor spaces to revert to more natural states. It’s also about the power of acting ecological just about anywhere. She's on the line now from New York City, where she lives, except when in Maine during the long days of summer. Margaret, welcome to Living on Earth!

MCNAMARA: Thank you. I'm so thrilled to be here. I'm a big fan of this podcast.

CURWOOD: So, tell us who is Daisy? What does she look like in her everyday life?

MCNAMARA: Daisy is a kid who goes to school like any other kid, but her passion, her, her heart, is all in the outdoors, and her particular area of the outdoors is not the mountains and the deserts, but it's her own environment, and she is a child who was born with a green thumb. I make a joke about how she was composting her own diapers at a very young age, but she is one of those kids who just gets obsessed, and you've seen it with dinosaurs or with trucks or with ballet and Daisy has that passion for the outdoors and for gardening. And she takes her gardening in a different area than her parents at first want her to do, which is to let the land go back to nature.

CURWOOD: So by the way, for some folks who may not be acquainted with the term, what is rewilding?

MCNAMARA: Rewilding is a movement in conservation where land, or tracts of land, or even small portions of land, are permitted to go to seed, as it were, to go back to nature. So you'll see a lot of people nowadays, especially in areas where wildfires are an issue, they will let their lawns, instead of being grass and turf, be comprised of indigenous plants that are hardier, harder to burn, promote more of a barrier. So kids can do this on a small scale. They could just take a portion of a lawn or space that they might have access to and see what happens when they don't cultivate it. Lot of grown-ups, adults do this on a much bigger scale with indigenous flora and fauna, and really encourage species to come back to where they originated.

CURWOOD: You might say it's just letting the weeds grow.

Margaret McNamara has written over three dozen children’s books, including How Many Seeds in a Pumpkin and The Apple Orchard Riddle. (Photo: Amy Wilton)

MCNAMARA: It's exactly letting the weeds grow, because what is a weed but a plant in the wrong place.

CURWOOD: You know, as Daisy proceeds rewilding, um, she's not very tidy, is she?

MCNAMARA: No, Daisy is not tidy. Daisy allows whatever nature wants to happen to happen. And as that takes hold in the land that she's tending, which is her front lawn, you begin to see the order behind that chaos, the natural order, which is plants that get sunlight and water thrive. There are plants that want to be close to each other, to feed off each other. There are insects who come visit the garden, and that has its own natural beauty and order, just like a meadow does or a lone oak tree. It may not be formal, but it has its own beauty, even in the chaos.

CURWOOD: Now your character Daisy is, may I say, a nonconformist. She has no trouble defying the rules of hygiene, for example. I mean, she doesn't want to wash.

MCNAMARA: She doesn't want to wash. Have you never known a child who also didn't want to wash? I mean, they're out there and the kids who don't like to take baths. Of course, this is a fantastical story, because Daisy starts growing weeds in her hair, and birds come nest in her, so it's not a for real story, but I think it endorses kids who are not averse to having dirt under their fingernails after they come back from digging, and kids who like to get dirty, kids who don't mind getting elbow deep in the soil. And there are kids like that, and there are more kids like that as this kind of movement goes forward. So no, I'm not saying that children should never take a bath, but I'm saying that this child decided not to, and decided to make her own science experiment, and lo and behold, now there's a book about her.

CURWOOD: Of course, now people like Stephen Trimble and Gary Paul Nabhan and Richard Louv would say that the natural place for a child to be is dirty in the backyard, digging from the very youngest age.

MCNAMARA: Exactly, I'm with them. I'm with them, even though I brought up a city child, I'm with them.

CURWOOD: So how important do you think nonconformists are to the success of, of dealing with the environmental emergency we have?

MCNAMARA: Well, that's an interesting question. I'm sorry that they have to be nonconformists to deal with this question. I wish they were the conformists who, just like everybody else, were concerned with the question of the environment. I think that Daisy's rebellion is pretty small. It takes place in the safety of her own backyard. Her parents know what she's doing. Her auntie Betsy is there to aid and abet. And I love that her wise parents call in the real gardener in the family. And so she's getting homeschooled. There's a page in the book where you see Daisy learning about photosynthesis to indicate that she's not missing out on her education. It is kind of a science experiment. So this is good for girls who are interested in the sciences, the STEM subjects. And by the end of the book, everybody in the neighborhood wants to conform to what Daisy's doing. So she does turn it on its head a little bit. She's not too much of a rebel.

Margaret McNamara gardening. She and her family live in New York City and spend summers in Maine. (Photo: Mr. Charles, Courtesy of Margaret McNamara)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, you have Auntie Betsy. How vital is it for adults to nurture and encourage kids who are paying attention to the environment?

MCNAMARA: I think it's crucial. And I'm lucky enough to have a friend whose name is Betsy, who is an avid gardener in Maine, who really has introduced me to gardening and to composting, her favorite subject. So I named this character after my friend Betsy, and she takes the very youngest little babies out into the garden, and she has them digging and watering and being responsible. It's a wonderful thing for children, I think, to be the responsible one who's going to bring the watering can and water the tomatoes, whether it's a tiny little pot outside of your window, or if it's a big bed, you know, in your expansive garden, to engage a child, to do that is a wonderful thing. And you do see initiatives like that. There's one here in the city called Harlem Grown. You probably know the folks involved in that, where empty lots are transferred into gardens and viable areas to feed people, the viable gardening beds to feed children and older people. And so I'm a big advocate of that. I came a little late to gardening in my life, but, you know, now I have the zeal of the convert, so I'm keen to imagine other people bringing their children into the gardens.

CURWOOD: So what's been the response from young readers encountering Daisy on these pages for the first time?

MCNAMARA: Well, I'll admit that the young readers I show this to tend to be kids I've met in Maine and kids who already have a vested interest in the environment. They love it. They love the idea that, like you know, you could start growing plants on your body, which children, you cannot do. But in this book, that's what Daisy does, and they love the imaginativeness of it. And they also enjoy that Daisy converts her neighborhood to her way of thinking, even though she's a child, but it's a very good way of thinking for the environment. A lot of them have been inspired by other young people who've worked as environmental campaigners, and they want to know what they can do. A small thing that you can do is even you know, three square feet of space or less, you can cultivate your own garden. It's not impossible. It just takes some determination and a little sunlight and soil and water.

CURWOOD: And let's face it, a taste for things like lettuce. Mean, it's not exactly easy to get a kid to eat lettuce.

Rewilding is a conservation practice that allows indigenous nature to grow with minimal cultivation. This photo shows the rewilding of Forty Hall, a historic manor house in the Enfield borough of London. (Photo: Christine Matthews, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCNAMARA: It's not but if they grow it themselves, then it's a whole different story. Because they see it as a seed. They plant it, they water it, they watch it grow, and then, you know, hey presto, they made food. And I've seen kids who wouldn't be able to swallow a fork full of broccoli, who are entranced by the idea of growing their own food, and who will eat it, and will find the joy in that and the taste in that, and then might not eat it again at the kitchen table, but they like it because they grew it themselves.

CURWOOD: So you know, at the core the book, Daisy Rewilds is a win for the environment. So what's the overarching message from this book?

MCNAMARA: Well, the message is that we ought to look around us and look at the available spaces that we have to invite the vital species back to our land, the species that belong there, whether they're the wild turkeys that appear in the book or simply butterflies, bees, worms. We need them to keep this whole crazy Earth going, and if we don't have them, we suffer. So my big message is, look around you, appreciate the natural world and see what you can do to contribute to its health.

CURWOOD: Margaret McNamara's book is called Daisy Rewilds. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MCNAMARA: Thank you. It was a wonderful conversation. Thank you so much.

Links

Author Margaret McNamara’s website

Real life rewilding explained by The Rewilding Institute

Purchase a copy of Daisy Rewilds (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth