Western Water Crisis Boiling Over

Air Date: Week of January 16, 2026

The Colorado River snakes through desert canyons in the American Southwest, supplying drinking water and irrigation for the region’s cities. (Photo: Alexander Heilner, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

The Colorado River provides water to seven western states, and there is not enough to go around. Recently the federal government ordered the states to agree on a plan on how to share what's left amid a worsening drought. Luke Runyon co-directs The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism. He joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss the challenges of allocating water resources when demand continues to outstrip supply.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The Colorado River provides water to seven states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. But the river has been overtaxed for decades. And recently the federal government ordered the states to come up with a plan on how to share the river amid a worsening drought. Lakes Mead and Powell, the two largest reservoirs on the Colorado River, are less than a third full, threatening both energy generation and the critical water supply for the population in the West. The river is also a lifeline for the region’s farmers, who need about 80 percent of the diverted water to grow crops.

Luke Runyon has covered issues in the Colorado River Basin for a decade. And he is co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism and he joins me now. Luke, welcome back to Living on Earth.

RUNYON: Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: Why is the Colorado River Basin considered to be in a state of crisis?

RUNYON: Well, the Colorado River is a really critical water supply for really the entire southwestern region. So about 40 million people rely on the Colorado River for drinking water supply; most of the major cities in the Southwest — Denver, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, Phoenix — rely on the river for some amount of its drinking water. It's also a really critical agricultural water supply. Some really productive farmlands in Southern California, Arizona, throughout the Southwest, rely on the river for irrigation water to grow food. And the big issue on the river right now is that our demand is outstripping the supply, and there's not enough water to go around. We've over allocated the Colorado River. We've known that we've over allocated the river for a long time, and really now the rubber is meeting the road in terms of instituting cutbacks to make sure that that water supply and demand is balanced.

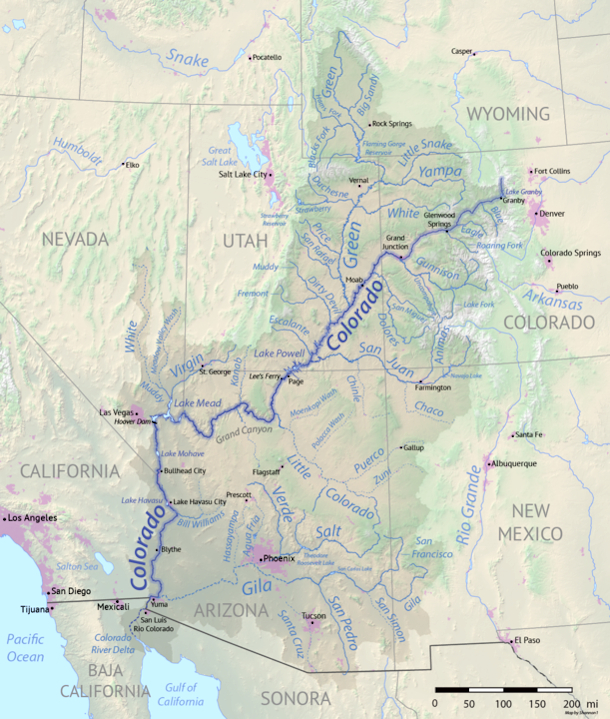

The Colorado River basin. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed, while California, Nevada, and Arizona make up the lower watershed in the US. The Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California use water from the river as well. (Photo: Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: What role does a warming climate play in worsening this crisis?

RUNYON: It plays a huge role, partly because it's speeding up conversations that needed to be had decades ago on the Colorado River. The Colorado River has been over allocated since its kind of foundational legal documents were signed back in 1922. The river never had enough water to satisfy all of the demand. As infrastructure was built out over the decades, that demand eventually outstripped the supply. So, we would be having an issue on the Colorado River, regardless of climate change. What climate change is doing is limiting the supply even further, and kind of catalyzing all of these discussions that are taking place around conservation. The way that that plays out on the ground is that climate change is upending how the water cycle in the Southwest functions. The Colorado River is snow fed. We know that less snow is falling in the southern Rocky Mountains. We're getting more precipitation as rain instead of snow. That has a huge effect on how the Colorado River behaves as in water supply and as an ecosystem. And the warming temperatures are also having all sorts of other knock on effects, like reducing soil moisture, so the ground that the snow falls on ends up acting like a dried out sponge, soaking up more of that snow when it eventually melts off, meaning it doesn't end up in streams and reservoirs. And so the warming temperatures have such a profound effect on how the water systems in the Southwest function, and we're really grappling with, how do we manage a system that is undergoing so much rapid change?

BELTRAN: Several years ago, there was an emergency agreement pushed by the Biden administration for Arizona and California to reduce their usage. Where does that agreement stand?

RUNYON: Well, leaders throughout the Southwest have come up with agreements over the past 25 years to try and address some of the issues that are going on in the Colorado River, namely, the scarcity, the water scarcity that we're seeing. And a set of guidelines were passed back in 2007— that's the operating guidelines that the river is currently under that guide how its largest reservoirs are managed. And after those guidelines were passed, conditions continued to worsen. And in the subsequent years, federal leaders, state leaders, would come back together every now and then to continue to kind of deal with that ongoing crisis. The latest agreement was this, it’s called the Lower Basin Plan, and came together a few years ago during the Biden administration. And it was really an effort amongst the Lower Basin states, California, Arizona and Nevada, to rein in their water use. But what we found is that even though there are some cutbacks that have taken place on the Colorado River, they're not enough. The supply is shrinking faster than we're able to curb our demand, and so the cutbacks that are needed now are significant in order to balance the supply and demand on the river.

Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, is a key piece of storage infrastructure for Los Angeles, Phoenix, and agricultural areas in both the U.S. and Mexico. (Photo: Ross Rice, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

BELTRAN: The annual Colorado River Basin Conference was held in Las Vegas in December. Negotiators from seven states were there. What was the mood at the gathering? You know? What were some of the highlights coming out of that conference?

RUNYON: I thought it was kind of like Groundhog Day, because the situation on the Colorado River hasn't really changed in the past year in terms of policy. The conditions on the river have actually gotten much worse. But this is an annual conference that takes place in Las Vegas every year, and you get everyone who cares about the Colorado River all in one place. And the situation on the river is reaching a really critical point, but the policy to actually manage the crisis in this current moment is not there. And what you get is a kind of really interesting interplay, and kind of a peek into the politics of water into the southwest, because the current issue that's going on on the river is that there is the set of guidelines, these 2007 operating guidelines that expire this year. And so the states on the river are trying to negotiate a future set of managing guidelines. And every now and then, the federal government, which operates these large dams that the Colorado River has, like Hoover Dam near Las Vegas, Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona, those dams are under threat of losing the ability to generate hydropower. So the federal government has an interest here in order to keep producing hydropower at these large dams. And the current stalemate when it comes to policy really comes down to who has to take cutbacks to their water supply under what condition and how much water are they talking about reducing their use of? And that's a really difficult conversation to have, because people see water as their future. States see water as an economic driver, whether that's for agriculture, whether that's for development and residential growth, whether that's for industrial growth. We've heard lots about data centers popping up in the Southwest. So leaders see access to water as the kind of foundation that the rest of their economy is built on. And so when you're talking about reducing the amount of water, people immediately think, how am I going to grow my economy without enough water, without access to this kind of foundational aspect of our society?

The Colorado River has been in a state of crisis for years due to a warming climate and increasing drought conditions. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: What are some successful examples of people using less water across the West?

RUNYON: A lot of it has come from, you know, kind of in different pockets, whether you're talking about farms or cities. In cities, it's been people replacing their old toilets in their homes that would maybe use like four gallons a flush. Well, you get a new toilet, it uses one gallon a flush or less. That's one small way that people can make an impact. It could be ripping out your front lawn and replacing it with water-wise landscaping, your zero scape landscaping. For farmers, it might mean changing your irrigation practice from flood irrigation, where you send water over an entire pasture, to something where you're moving to a sprinkler system that uses a lot less water. For large cities, sometimes that means installing, you know, a water recycling plant where you're treating your effluent, your wastewater, and making it drinking water again. We have the technology to do that these days, and so it really is just kind of it varies across the entire basin depending on what your resources are, what your needs are, how you might go about using less water.

BELTRAN: And we're talking about seven states here across the Colorado River Basin, you know, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and California. Some of these states are red and others are blue. How does politics play a role in this debate?

Luke Runyon is the co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder. (Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

RUNYON: Well, water is one of those interesting issues that doesn't fit neatly into our partisan divides that pop up in almost every other issue in American life these days. More often than not, it pops up in sort of a rural, urban divide. And so you do, you have kind of a mix of really conservative states and really liberal states. You know, everywhere from Wyoming, one of the most conservative states in the country, down to California. So it is an issue that doesn't neatly fit into those kind of paradigms that we have, blue state, red state. And I think, you know, I mentioned that the federal government is involved in some of these talks as well. I think the federal administration does not really know how to make this a partisan issue, which is why they've kept an arm's length at some of these negotiations. I think if it was one of those issues that neatly fit into our partisan politics, they would have already turned it into a partisan issue, but instead of have kind of kept this whole debate at arm's length and are really letting the states kind of guide the discussion.

BELTRAN: What are the major obstacles to finding a viable plan here?

RUNYON: The obstacles are huge. I mean, you you have this is sort of something that is in the psychic mentality of how the Southwest was settled. You know, these kinds of fanciful ideas of how much water the Colorado River could provide. And you know, this is a huge paradigm shift for the region too. For decades, the conversation in the Southwest has been, how much more water can we get from the Colorado River? Where's the next big infrastructure project? Where's the next straw going into the river to draw for name your big metropolitan area? That has shifted very recently. No one is talking about big new projects in terms of additional water supply, and that's because there's just not the water to meet the need. And that is a massive paradigm shift for the entire region, because it moved from where does my next drop of water from the Colorado River come from, to Oh, no, I don't have enough water. No one has enough water, and we all have to reduce our use. That's a big shift in the mentality of leaders in the Southwest, and it's taking place right now.

BELTRAN: To what extent has Manifest Destiny been a part of the conversation around water use across the West?

Antelope Point marina is located in the dwindling Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir and a crucial part of the Colorado River water supply. (Photo: Alexander Heilner, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

RUNYON: I think it's huge. I mean, you know, this is a very arid region that was settled by European colonizers back in the late 1800s, early 1900s with federal incentives for land and agriculture. And when the kind of initial management conversations were happening around the Colorado River, around the turn of the century, the 1920s, no one was talking about the environment. No one was talking about the needs for Native American tribes. No one was talking about the needs for recreation and a recreation-based economy. It was all about consumptive use for agriculture and for cities. And so over the subsequent century, what we've seen is that those other powers, those other interests on the river are trying to assert themselves and really kind of stake a claim, saying, like, we deserve access to water too. The river itself deserves to have some allocation of water that it's not just a water supply, it's an ecosystem. It's a, it's an environmental force in in our region. And so I think that that conversation continues to today.

BELTRAN: Luke Runyon is a veteran journalist and co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism. Luke, thank you so much for joining us.

RUNYON: And thanks so much for the conversation. I had a great time.

Links

Read more on how the federal government is planning to address a dwindling Colorado River.

KUNC | “Feds Publish Possible Playbook for Managing Dwindling Colorado River Supply”

Look into the new guidelines for operations at the Colorado River post 2026.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth