A City on Mars and the Perils of Settling Space (Cont'd)

Air Date: Week of January 2, 2026

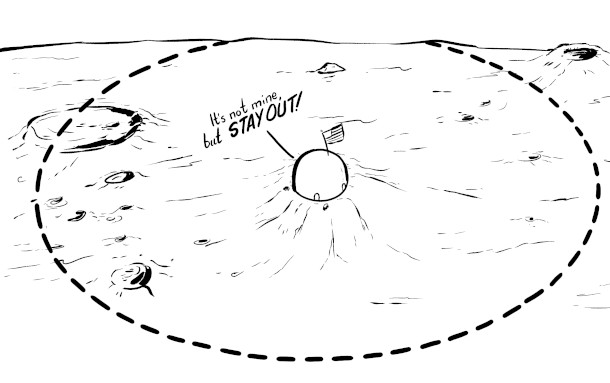

Space exploration could set the stage for territorial conflicts. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

A City on Mars authors Kelly and Zach Weinersmith continue their conversation with Host Jenni Doering about the challenges of settling space. They discuss why the Moon has limited “primo” real estate, what it was like to write this book together as a married couple, and why they view humor as an essential piece of helping a general audience understand such complex issues as international space law.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. And we’re back now with Zach and Kelly Weinersmith, authors of A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? And, Kelly, I gather something that space settlement enthusiasts should probably “think through” a little more has to do with the law. So, why did you feel that it was important to cover international space law in this book?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Doesn't “space lawyer” sound like the job in a science fiction novel? Like it took me forever to be like, "Oh, this is a real field." But, I mean, it's a field that could get in the way of space settlement dreams. So for example, Elon Musk would like to see a million people on the surface of Mars in a self-sustaining settlement in the next 20 to 30 years. And his company Starlink, which is his satellite internet company, in their terms of service, it says something to the effect of, when humans get to Mars, they will not be beholden to the government of Earth. So he would like to start it sounds like his own nation, and that straightforwardly breaks international law. So in 1967 a treaty was ratified through the United Nations. That's now called the Outer Space Treaty. And it has a lot of important stuff in it, like, you can't put nuclear weapons in space.

DOERING: Good idea.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah, I, totally behind that, because at the time, we were setting off a lot of nuclear weapons in space, and it was causing problems and making people very nervous, as you can imagine.

DOERING: Yeah.

The Outer Space Treaty states that the supervising nation is legally responsible for both governmental and non-governmental activities in outer space. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah. And another part of it says that you're not allowed to claim sovereignty over anything in space. So when we landed astronauts on the moon, and they put down an American flag, that was not claiming that the moon is ours, that was just like a symbolic, uplifting act. But it sounds like Musk would like to be able to claim something as their own, or something as the ownership of whoever goes out there, like the first group of Martians. But the Outer Space Treaty also says that well, according to international law, anyone who goes to space is the responsibility of some nation, and so if SpaceX sends a bunch of people to space, they will probably be the responsibility of the United States, which means they really can't be starting their own nation in space and claiming that territory as their own.

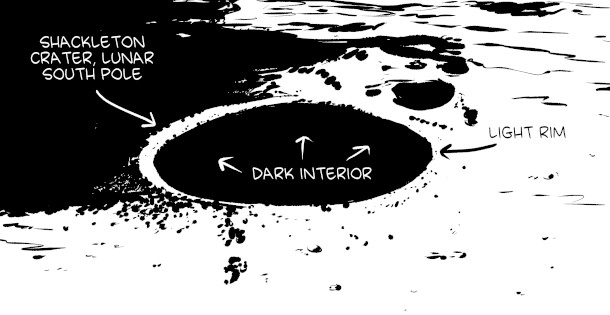

DOERING: Until reading your book, Kelly and Zach, I had no idea that there is special primo real estate on the Moon. Why is that?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: So the Moon is a particularly horrible place to be. So at the equator, I think it swings from something like negative 130 degrees Celsius to positive 120 degrees Celsius, whether it's day or nighttime. So that's a swing of 250 degrees Celsius that will kill you with cold or kill you with heat in either direction that you're in. Additionally, it's got that regolith, so that very abrasive fine dust, and so there's some concern that if you breathe it in, it's going to scar your lungs and cause stone grinders disease, just a very harsh environment, and the regolith has a little bit of water in it. But technically, that's also true of concrete. But concrete is wetter than the regolith.

DOERING: We're talking dry concrete.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah, very dry concrete, yeah. And so if you want water on the moon, you have to go to the poles. And in the poles, there are these craters, and inside the craters there's water trapped as ice, and it's so cold that it's like rock, but it's still there, and it's contaminated. It'll need to get cleaned up, but there's water there. And those craters are also important because the rims of the craters would be great places to set up solar panels. So if you are at the equator, you have a period of time that's equivalent to two weeks here on Earth where you're in total darkness. So their nights are really long, and the number of battery packs that you would need to bring with you is prohibitive. So we're probably not going to be relying on solar power at the equator.

DOERING: That's a long, cold night. Two weeks.

The light rims found on the edge of the craters on the Moon would be ideal places to put up solar panels (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

KELLY WEINERSMITH: A really long, cold night followed by a blisteringly hot day. But if you're at the poles, the temperature swings are way less extreme. And because of the way that the moon is tilted, if you're on some of those rims, you can get sunlight almost all the time. So they're called the peaks of eternal light, and they should probably be called the like peaks of almost sort of eternal light, because you get it like 93% of the time. But that's much better. And so you can set up solar panels there and have a reliable source of power. And then you're next to these craters of eternal darkness, which is where you get the water. And so most of the proposals from NASA or the Chinese space program that talk about where they want to, like, set up research stations or land and think about staying for a while. You're looking at the poles, and this is a very small surface area of the Moon. And so we are set up for a scramble for the best parts of the Moon because the Moon kind of all looks the same, but you definitely just want to go to the poles.

DOERING: You know, given that some of the most powerful and wealthy people in the world, we're talking Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, not to mention rival nations, have a keen interest in sticking a claim in space, whether or not that's legal, how hopeful are you that International Space Law can, like, reign in the most dangerous impulses here to just go out and use up resources and take control?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: We're a little nervous. I think it would maybe be an understatement. So you know, one of the problems is uncertainty. So you can't go out and say, "This is mine." But for example, if the United States or China got to the poles of the Moon, where you can find some water, if they got there first, there's nothing stopping them from setting up on what is arguably the best part of the Moon and then saying, "Okay, it's not safe to come in this area, because I'm working on some stuff. And if you land your rocket, you're going to hit me with debris, and that could be bad for my people. So nobody else is allowed in this area. And I'm not saying that it belongs to me, but I also don't plan on ever leaving." And that's sort of quasi sovereignty. It certainly feels like sovereignty. So I would love to see more clarity for international law. And you asked how optimistic I am that we're going to get that. There's reasons to be optimistic. It does seem like we're getting clarity on the resource question we talked about already. So the Artemis Accords came out through NASA in 2020, a lot of nations have signed, and that does essentially say we all agree that it's okay to go out and extract resources and sell them, and that we're all cool with that. So like, a consensus does seem to be building there, but no treaties have been ratified that bind the behavior of the major space players through the United Nations in like 50 years, and so I'm not optimistic that we'll get a treaty to solve these problems.

A “quasi-sovereignty” could hypothetically be set up at one of the poles of the Moon without directly being claimed. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: So Kelly, Zach, as a couple, what was it like writing A City on Mars together?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: You gonna let me have that one? [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Well, I'll get my say. You can start.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Well, all right, good. Good. Good. Disappointingly non-dramatic. I kind of wish someone threw a chair through a window at some point, just so we can report it.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: No, I mean, you know, our last book, Soonish , we kind of just say, "Well, you do a chapter and I'll do a chapter, and then we'll come together." For this, we kind of had to, like, divide and conquer according to aptitude. So like, our joke was, you know, Zach reads very quickly with about 80% comprehension. Kelly reads very slowly with 100% comprehension. So essentially, like, I was vanguarding into, like, I'm gonna read a bunch of astronaut memoirs, and I'm gonna read all these, like, old books about the space future and this and that, and Kelly was often the one with the task of, like, NASA has 150 pages on the effects of radiation, with like, 8 billion citations. Kelly's going to read the whole damn thing. Essentially, the workflow we ended up with was we would both research and then we dropped these into a giant pile of notes in Google Docs. We like, literally have 1000s of pages of notes on all these different topics, and then Kelly, for a given chapter, would collate all of those notes and then create something we call the dossier, which is was a sort of like 30-page version of something that needed to be five or six pages with suggestions of structure and, like high points and quotations that might be amusing. And then my job was to kind of swoop in at the end and make it a little funny and jaunty, and then endless rewrites. But essentially, you know, we had to, like, play to our strengths because there was no way to get it across the finish line, otherwise. In terms of us not yelling at each other, I think the main thing we had going for us is that we really just cared a lot about this project. This wasn't just like a meal ticket for us. We spent, like, a decent amount of our careers on this. And so, like, the part where your spouse is like, "I think you wrote this badly, and you should start over." What you want to do is say... Well, I don't want to say. But, but what you do is you say, "All right, fine. I will because as much as I don't want you to tell me I suck, I really don't want the world to tell me I suck." And so we would go back and rewrite together, and no one had to die.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

Zach’s rendering of Kelly and himself. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: [LAUGHS] And Kelly, what was it like for you, and if I may, how did it change your relationship?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: You know, I think Zach did a really good job of describing what the experience was like. There were so many instances where I would send a draft of the chapter to Zach and he'd be like, "What? No, this is all wrong." And then he'd send me a draft of the chapter, and I'd be like, "Are you kidding me? This is all wrong." And I think we both eventually got good at accepting that particular kind of criticism. I don't feel like that has translated into like, "Oh, you didn't do the laundry."

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Somehow that still hurts—

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: —you know, when it comes from either of us, but when it comes to like, "This writing isn't quite working," we've managed to sort of scrape our egos out of the equation. And we'd focus on, "All right. Well, we need to get the best version of this done." And we got pretty good at accepting each other's criticism when it comes to writing over the course of the four years.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: But there was, there was the one fight.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: There was... no, there were two fights.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: You know what I'm talking about.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: There were two fights.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: What were the two fights?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Google Docs versus Word—

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: —and has sex ever happened in space? We came down on very different sides of that argument.

DOERING: [LAUGHS] All right, so we got to settle this. Which one of you thinks sex has happened in space and which one of you does not?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: I think it has.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: I mean, all right, listen, my wife's mind is in the gutter about this.

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: I think the problem is, all right, you can't just sort of, like, take the amount of time and multiply through because otherwise, you would have to apply this logic to every place that's ever existed. Like, like, has anyone had an excursion in the like, containment chamber of Chernobyl? Well, it's been there a while. Okay, okay. You think that's happened too, never mind. But the bigger issue is, like...

KELLY WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS] Are you retreating already?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: It's easy to say... What?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: It feels like you're retreating. Go ahead. [LAUGHS]

The particulars of human reproduction in lower-gravity environments than Earth require further scientific study to be fully understood. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS] No. Okay. But listen, you're working in theory. I'm working in practice. You could say it's been a long time with lots of people but you cannot pinpoint where it could possibly have happened. You know, you want to talk about what was it Jan and Mark Davis, who were newlyweds, and they go up in the space shuttle, but the space shuttle has the living space of a bus, and there are seven people in it, and so they have, like, a week and a half to make it happen. So the only possible opportunity is for there to be a seven-person space sex conspiracy that hasn't been revealed for 30 years. And I just don't believe it.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: I am surprised by your lack of creativity, and I will point out that an absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence. So anyway, we'll let it go now.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yeah. All right. [LAUGHS]

DOERING: All right. So still a mystery.

KELLY WENERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

DOERING: Now, so Zach, one of the things I haven't really asked you too much about yet is all the wonderful cartoons in this book. There's a lot of unique things about this book, but they make it really fun. So what was that like, taking the material, making sure that you're communicating the information, but also then being able to make cartoons about it?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yeah, so you know our view of pop science is that, essentially, you're trying to take something big and make it palatable for a general audience. And you can either water it down enough that people will roll with it, or you can at least try to give people the real thing, but put enough sugar on it that it'll go down. I think that actually can be non-trivial. Like if you're talking about something complicated, and you tell a joke, the audience relaxes and can say, "Okay, maybe it's not that hard to understand." To be frank, the most boring thing was international law to research. Not that there weren't like occasional oases of funny stuff. I mean, it's thick and it's written by lawyers. It was just very hard. And so trying to take that and say, "How do we go to a normal audience and make this interesting? Because we think it's important. It's part of the picture. It's almost always skipped." You basically have all the most powerful nations on Earth saying how they feel on paper. You have to understand this. And unfortunately, it exists in a whole milieu of history which you kind of have to understand. So it was like, how do we make this palatable? So, like, there's a comic, and it's one of the few comics that really doesn't add anything intellectual, but it's just...we discovered this anecdote that actually happened where the Nazis tried to claim a chunk of Antarctica, and literally, at one point this is documented, they came out and heiled a penguin. I think it was an emperor penguin. And I remember reading that and being like, "This is going to get us through how does Antarctic treaty law work." Generally speaking, most of the illustrations actually provide a kind of diagram or an intellectual addition to the topic, but a lot of them are just there to get you through it, to say, like, "Come along with me. I'll tell you a few jokes and stories. I'm sorry you have to understand this." So that was the approach.

In the process of the Nazis trying to claim a chunk of Antarctica, they 'heil’ed a penguin. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

KELLY WEINERSMITH: And our editor is such a saint, because she was like, "How many chapters on how international law applies to space do you want to write?" And we're like, "Five?" And she was like, "You guys better be really funny." [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

DOERING: I think when people envision humans going out into space, sometimes there's this idea that we're just going to be like, better people up there were going to be different. What do you make of that idea?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: So you're referring to an idea put forward by philosopher Frank White, and it's called the overview effect. And the idea is that viewing Earth from space has a bundle of goods, some of them being you know, you decide that borders don't really exist, and we should all be getting along, and that the Earth is this fragile system that we need to take better care of. And it's a beautiful idea, but we haven't found much evidence for it, either in the literature or in the memoirs that we read. So one, it's worth noting that you can see borders from space. You can see the border between India and Pakistan that's lit up. There's a lot of conflict there. You can see the border between South Korea and North Korea because North Korea is dark at night and South Korea is not. So our problems are, in fact, visible from space. And the many astronaut memoirs that we read, they would come back from space, and they would still be humans. You know, they would still cheat and lie and you know, they're way better people than Zach and I are in a lot of ways, but they're still human beings. I think we're human beings on Earth, and we're going to be human beings in space. We're going to bring our problems with us, and I think you need to be clear-eyed about that.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: This pertains to, we will not be angels in space. So this happened in 1975. Most people don't remember. It was called the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. And the very short version is it was the first time the US and the Soviets docked together in space. And so you might think this is the perfect place to say, "You see, in space we transcend, and we are better than ourselves." Well, John Young wrote about this in his memoir. He's an astronaut's astronaut. He was one of the Apollo guys. He was one of the pilots of the first space shuttle. He wrote about how there was a dispute on Apollo-Soyuz Test Project over who was going to be which part of the dock. And as he put it, "Nobody wanted to be the one getting the business." This was a non-trivial dispute. Apparently cost a huge amount of money. By the end, they had to create an androgynous docking system because they couldn't agree to who got to be the boy and who got to be the girl. Okay, so this idea that we're going to stop being humans in space is just absurd. In addition to there being no evidence for it, there's tons of evidence against it.

DOERING: That's such an interesting reflection, too, on gender dynamics. And, you know, I imagine nobody wanted to be the so-called female end. [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: That's right, yes.

DOERING: Yeah.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: It was the female end nobody wanted to be, yeah. Well, and the first woman to step foot on a space station was handed an apron. And so yes, our gender issues follow us to space as well.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yes.

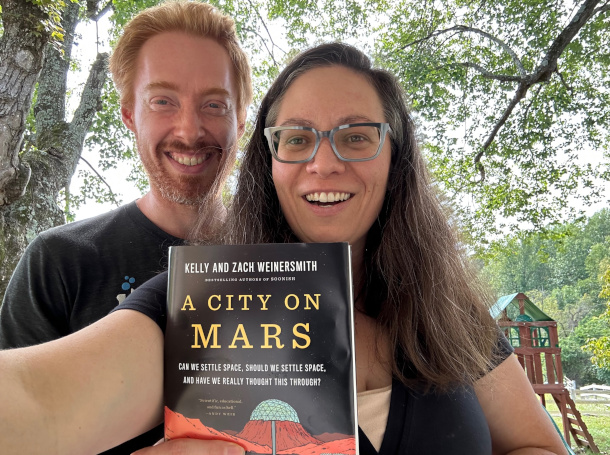

Zach and Kelly Weinersmith pose with a copy of A City on Mars. (Photo: Courtesy of Zach and Kelly Weinersmith)

DOERING: Well, what do you hope that readers take away from this book?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: So we try not to be wet blankets, literally 100% of the time. So the uplifting message we like to send is that there's a lot of cool work that needs to be done. There's a lot of really awesome research projects. There's a lot of really important international law. And I mean, if you're in international law right now, you could be helping to establish the rules that guide humans as we move through the cosmos. Like, that's an amazing job to be involved with. And the scientists who get to run a research station on the moon to look at rodent reproduction, like that sounds really cool to me. And, you know, trying to figure out these closed loop ecosystems, figuring out how to recycle resources better, that could help Earth. Like there's so many cool questions with so many cool side projects that I think getting excited about being part of the generation, or generations, that get us ready for settling space is worth being excited about, even if I don't think we'll be settling space within my generation. I had to end on a, you know, sort of negative point because that's who I am. [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS] It's what you do.

DOERING: And Zach, any final thoughts?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Oh, well, just to echo Kelly. I mean, I think often in science, there's a kind of like, hype pop version of things that sounds really cool, but often, you know, the truth is often much more interesting than the hype version. It just takes a little effort to understand it. And so I worry there have been a lot of people who like, feel like they're on our side, who go on the internet and are like, "According to Kelly and Zach, you will never colonize space, so stop trying." We don't say that! Never is a long time. And in fact, we provide a roadmap at the end to the stuff you'd need to do. And it's all amazing. So we think it can happen, and we are in no position to predict the future. So even if we never do this, or none of us live to see it happen, all the stuff we do in the interim is amazing.

DOERING: Zach and Kelly Weinersmith are the co-authors of A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space? Should We Settle Space? And Have We Really Thought This Through? Thank you both so much. This has been really fun.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Thanks. We had a blast.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yeah, thanks for letting me argue with my wife about sex on the radio. That was...[LAUGHS]

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS] Highlight of the marriage!

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

Links

Purchase a copy of A City on Mars (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth