A City on Mars and the Perils of Settling Space

Air Date: Week of January 2, 2026

Authors Kelly and Zach Weinersmith combined their science and science-fiction interests and created a book on space exploration, with the intention of taking a complicated set of topics and making it fun and engaging. (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Press)

As a new space race heats up, private companies and sovereign nations alike have their sights on setting up permanent human settlements in space – but huge technological, medical and legal challenges remain. Biologist Kelly Weinersmith and cartoonist Zach Weinersmith are a married couple who teamed up to write the 2023 book A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? They join Host Jenni Doering to chat about the comically hostile environments beyond our home planet.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Fewer than a thousand humans have ever been to space, and no one has yet traveled beyond the Moon. But as a new space race heats up, private companies and sovereign nations alike have their sights on sending humans to Mars and beyond and setting up permanent settlements in space. That’s easier said than done, since we’re adapted to the atmosphere, climate, geology, ecology, gravity and more of this planet, Earth. Well, a fascinating and at times hilarious book from 2023 takes a deep dive into everything we’re gonna need to figure out to make long-term life in space feasible. The title is A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? And it’s written by Zach and Kelly Weinersmith, a married couple who team up to write popular science books. Dr. Kelly Weinersmith teaches biosciences at Rice University and is the co-host of the podcast Daniel and Kelly’s Extraordinary Universe. And Zach is a professional cartoonist who you might know from his webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal. Though their book A City on Mars does explore the feasibility of settling the red planet, it takes a big picture look at the technological, medical and even legal challenges of settling space in general, whether that’s on Mars, the Moon or permanent floating space stations. Kelly and Zach Weinersmith are here with us now—welcome to Living on Earth!

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Thanks so much for having us.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Thanks for having us.

DOERING: So how did you get interested in this space settlement conversation?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Well, we are both sci-fi geeks, and we wrote a book together called Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve and/or Ruin Everything. And in that book, there were two chapters related to space, one about cheap access to space, and the idea there was that SpaceX is dropping the cost of launching mass to space. And another chapter about asteroid mining, the idea there being we can go to asteroids and extract things like metals. And both of those communities were telling us that, like these are the keys that you need to unlock space settlements. So space settlements are just around the corner because we can send the habitats that we need up to space, and we can get the other resources we need from asteroids. And as sci-fi geeks, we were super excited that space settlements were just around the corner, so we decided to write the guide to the next decade of humans settling space. And that's not the book we wrote, because about two years in, we were like, "Oh man, there's so much more than just sending mass to space."

DOERING: [LAUGHS] Yeah, Zach, that must have been a little bit of a surprise to find that you guys were taking a little bit of a different approach than you had first envisioned.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: I'm sure it was for our editor. [LAUGHS] I remember it as if it were like a single kitchen table conversation, but like we were both doing these crazy amounts of research, and for a big research project, it takes a while for the picture to resolve. And I think it was about two years in, we'd been talking, and slowly the conversation had steered toward a like, "Maybe this isn't going to happen. Maybe this, there are parts of this that shouldn't happen." And so we decided, as we come back to our editor, or maybe she came to us first. I think we kept changing the chapters to be more toward this, but we were trying to keep a neutral stance. And at some point she was like, "Clearly, your thesis has changed. Could you please make the book reflect that?"

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: And so we did, and once that was sort of intellectually open to us, then we could kind of, I don't want to say building a case. I think we tried to be as neutral as possible. But like, have a picture that wasn't completely enthusiastic.

Kelly and Zach Weinersmith are the co-authors of A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? (Photo: Courtesy of Zach and Kelly Weinersmith)

DOERING: Of course, you had to change tack partway through this project, and your book opens with a dedication that reads in part, "To the space-settlement community. We worry that many of you will be disappointed by some of our conclusions, but where we have diverged from your views, we haven't diverged from your vision of a glorious human future." So tell me about your relationship with the space-settlement community.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: We get invited to fewer space parties these days—

ZACH WEINERSMITH: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: But they've been actually really good sports for the most part, so that, you know, there are a couple people who are very angry at the book and very angry at us, but for the most part, we keep getting invited to space-settlement conferences to present our take on things. And we're usually presented as the like, "All right. Here's the segment that no one really wants to hear, but here's a reality check, and then we'll go back to being optimistic and amazing once the Weinersmiths leave the room." But they've been welcoming and nice to us.

DOERING: You guys are kind of the skunk at the picnic, I guess in some sense.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yes.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah, yeah, we are.

DOERING: Well, the subtitle of your book, A City on Mars, includes the line, "Have We Really Thought This Through?", which I think says it all. So, let's get right to the point. Just how inhospitable is Mars?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Mars is bad. So let me just go down the line quickly. Mars has a very thin atmosphere, which means if you go outside, you die. It's about 1% Earth's atmosphere. It's made of carbon dioxide, mostly. That thin atmosphere also means you're very exposed to radiation from space. That's compounded by the fact that Mars is very weakly magnetic. So on Earth, we have this magnetosphere, so that when all these nasty bits of radiation, these hot ions, come from the sun, the magnetosphere bottles them up, delivers them to the poles and gives us a light show. Mars doesn't do that. In addition, Mars has about 40% Earth gravity. That's probably bad. But, to be honest, we don't really know. Most of our data on humans off Earth is in zero gravity on the International Space Station. And, you know, weird things happen at zero, so we don't know what 40% is like. The surface is laden with a chemical called perchlorates used in dry cleaning. We don't have a lot of data on long-term high-level exposure in humans, but we know exposure to it disrupts thyroid hormones. So that's not ideal, especially not ideal if at some point in this conversation, we talk about reproduction. I do want to emphasize though, like, Mars is the best place. Mars, Mars, Mars is the best option.

DOERING: [LAUGHS] Why is that?

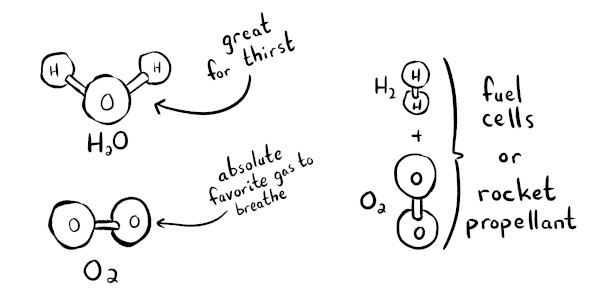

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Well, you could say because everywhere else is worse. Look, if you're on Mars, here are the upsides. One, there is, by space standards, readily available water, not Earth-available, but available. So like the Poles have lots of water ice. It appears that if you dig down far enough at many, even most places on Mars, you eventually get to some water that you can access. Mind you, it has to be cleaned, which is not ideal, compared to Earth, where you it's much easier to get access to water, but it's there. And so water, if you do a little chemistry on it, it's not just water for you to drink and shower and have water balloon fights. It's like... you can crack it into hydrogen and oxygen, which doesn't just mean you get oxygen, which we like to breathe. It also means, you know, hydrogen and oxygen are some of the best rocket propellants when you combine them. If you can get access to water, you've done a lot of the job. In addition, Mars has like the elemental buffet needed to survive. It's made of roughly Earth-like proportions of stuff. And that matters because the best alternative, which is the moon, is not. The moon is poor in all sorts of stuff. So one way to say it would be, Mars gives you a chance, almost everywhere else, not really.

In the right circumstances and with the right kind of chemical reactions, water can be utilized not only for drinking and bathing, but also for manufacturing oxygen and rocket propellants. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: You know, one of the subheadings in your book is, “The Sun Wants to Kill You,” and then the next one is, “The Whole Universe Wants to Kill You, Actually.” So part of that is radiation. Can we just back up a little bit and talk about like, why is space so dangerous when it comes to radiation?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yeah, so it's actually a bit of a nuanced picture. So first of all, the sun is just kicking out dangerous radiation all the time. And there's also another source of radiation called galactic cosmic radiation that isn't completely understood, but just if you want to visualize lots of heavy ions zooming through space, crisscrossing your body all the time, that's what space does. Now, you know, we hasten to say, it feels like sometimes people talk about this like it's going to kill you instantly. It's much more like it's going to probably, non-trivially, increase your risk of cancer.

DOERING: Yeah.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: You know, we actually really tried to dig into this, because it's complicated to know what the effects of radiation in space are on humans because humans don't normally experience this. Astronauts haven't been up that long. I think the record total for an astronaut is something like 800 something days, and the record consecutive total is 437 days. Most astronauts much shorter. So we have really limited data. The data we do have on radiation on Earth comes from like disaster sites, things like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, times something really bad happened. But that's obviously not equivalent to the kind of radiation you get in space. So we don't actually know that much. In addition to all that, the sun, from time to time, just sort of belches out these sprays of radiation, like we call it a flashlight beam of doom.

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Your best defense against this is that space is big, so it probably won't hit you, but it could happen. You know, if it happened while you were in a spaceship and you didn't have a lot of protection, you would just die, and you would die in one of the worst ways imaginable, which is acute radiation sickness. There are also cases from history when the sun shot one of these at Earth. So we document a few of these cases in the book. But essentially what happened is, you know, these stories about like the telegraph era, telegraph machines are suddenly like firing sparks around the world. There are strange lights in the skies. And you know, we haven't really experienced this in a technologically developed world where it would probably be quite bad, but manageable. But if you imagine you're in a habitat on Mars and you're deeply dependent on technology, it's much more scary, which is why you will be underground.

DOERING: Oh my. What was that phrase? “Flashlight…” [LAUGHS]

ZACH WEINERSMITH: “Flashlight beam of doom.”

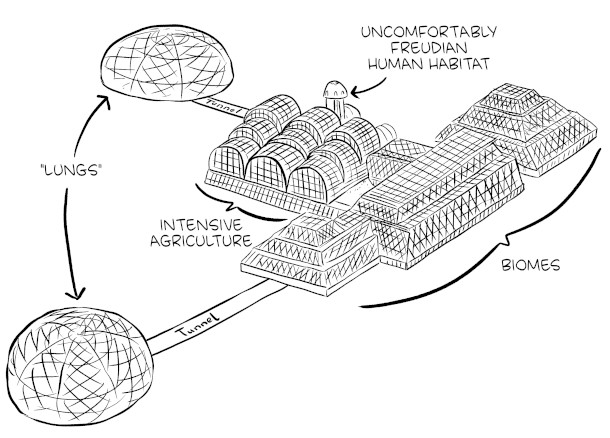

Because of the dangerous amounts of radiation from the Sun and outer space that reach the surface of Mars, human habitats would likely need to be underground and covered by dirt. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: Wow. Kelly and Zach, your book covers three main areas of study that need to advance for humans to settle space: technology, medicine and the law. Let's start with the first one. Technologically speaking, how far away are we from being able to build a space settlement community?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: I'd say we're pretty far. Space is a really difficult environment to do engineering in. The surface of the Moon and Mars are covered with this fine, jagged dust called regolith. And Zach already talked about this a little bit. It's got those perchlorate chemicals in it, but they're going to sort of grind up the equipment that you want to use. Additionally, we have to worry about how we're going to get power out there. So Mars, every once in a while, has planet-wide dust storms that last for like, weeks at a time, and so you're not going to want to rely on solar power. So we're probably going to need portable nuclear reactors, and folks have been working on these, but they're not quite scaled up to the level that they could sustain a settlement. But another big technological problem is that we haven't really established habitats that can recycle a ton of stuff. So you know, Zach talked about how hard it's going to be to get water on Mars. And on the International Space Station, we've gotten pretty good at recycling water. And, in fact, the astronauts refer to the water that they're drinking as yesterday's coffee because even the urine gets recycled. So we have some experience with that, but we don't have experience with recycling a lot of other stuff. So ideally, you would have plants that are both food and the method for extracting carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and giving you more oxygen. We've done some experiments of this type. So for example, there's a facility in China called the Lunar PALACE. And they managed to recycle all of their water; they managed to grow a lot of their food; but they had some trouble with the breathing gasses. And so, at one point they had three big guys in there, and the carbon dioxide levels were just going up and down, and they were wild and all over the place. And so, they switched out two big guys for two small women, and then it was okay. And so needless to say, if you had that problem on the surface of Mars, you'd be dead. [LAUGHS]

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

One major technological challenge for the possibility of living on Mars lies within the agricultural sector and the recycling of resources, such as plants. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

KELLY WEINERSMITH: So figuring out these closed loop ecosystems is going to be important. And then, because of the radiation problem, Zach talked about earlier, we're going to need to figure out how to get our habitats underground because we'll need that like dirt to protect us from the radiation. And so, figuring out how we're going to dig or cover our habitats in dirt will be difficult.

DOERING: We are going to need to eat on Mars. Why is local food essential up there? Zach?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Well, I mean, so, you know, local food would be great, essentially, because the alternative is to ship it 10s of millions of miles through space. So ideally, what you'd want to do is build one of these closed loop ecologies that Kelly's describing, and then just recycle as much as possible. That way, you can essentially make use of the incoming energy from the sun on Mars, which is lower than on Earth, but still pretty good. And you know, one way to think about it is, we really take for granted all the stuff Earth does. Right? You don't worry most of the time that if you go outside, you're breathing something that might kill you. If you're in a sealed container, and it is going to be sealed, you really need this biosphere to be enough to cleanse everything bad while providing you tasty food and getting rid of your waste.

Sustainable agriculture and local food would be an essential part of the closed loop ecosystem while on Mars. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: You know, I have to say, a lot of the food we grow here on Earth is not the most sustainably grown, and it takes a lot of resources. And I don't know how feasible that would be up on Mars. So what are some of the ideas for how we actually get enough of the nutrients that we as human beings, biological beings, need?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: This is an area that absolutely needs a lot more research to try to figure out exactly, you know, how many calories do humans need? What plants are the most reliable? How can we make sure that you have enough calories when one crop is done and the next crop is partway through its growth? These are difficult problems, but you can also imagine that this research, once we figure it out and figure out how to recycle and do this stuff more efficiently, those answers could be helpful for us here on Earth. But another problem is trying to figure out where we're going to get our protein from. So some folks that I spoke to at conferences argued that probably being a vegetarian is going to be the way to go. So our protein will come from legumes or fungi. But other folks argue that we'll have to end up getting our protein from insects. So chickens and pigs and cows, these animals are too big to bring to space. They create too much waste. They would need too much surface area, and additionally, they're not super efficient at converting the like vegetation that you give them into calories, and so you probably won't want to bring them. But if you bring insects, you can feed insects on the waste part of plants that humans don't eat, and then you can use them as a protein source. And so, in that Lunar PALACE facility that we talked about, they took the waste from the plants that the humans couldn't eat, they fed that to mealworms, and then they cooked up the mealworms as their source of protein. And we've also seen suggestions for crickets and termites and some other kinds of insects. Hopefully you don't have any wooden structures in your habitat. Probably you won't, but anyway, not a diet that sounds amazing to me, but you know, if you're hungry, anything works.

DOERING: Mm, delicious—mealworms, termites, crickets maybe I'd be okay with.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah. Our daughter has eaten crickets and liked it.

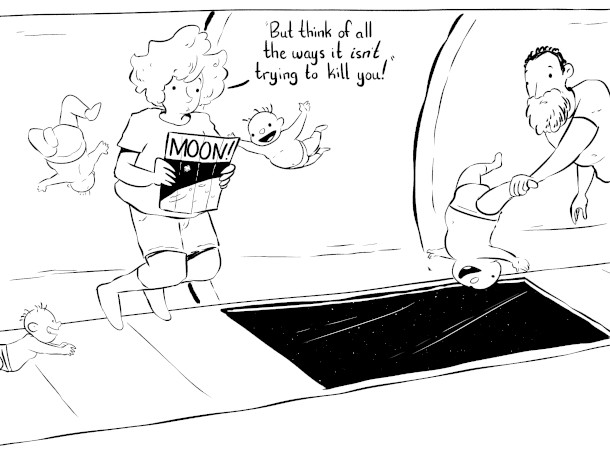

DOERING: One of the funniest and most fascinating parts of the book talked about the delicate subject of sex in space. What do we know about sex in space?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: What we have found a lot of people who have spent a lot of time thinking about sex in space, many pages written on the topic, even though there's not a lot of data to work with. So it's not clear if anyone has ever had sex in space. There are a couple of times when people propose it could have happened. There was a married couple on the shuttle that managed to go up there before NASA found out they were married. But there's no definitive evidence that anything happened. A lot of folks have tried to engineer solutions, let's say to the problem that when you push against something in space, it gets pushed back because you don't have gravity to sort of hold things down. We are fairly certain that humans will solve what we call the docking problem—

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: But the problems that come after, including reproduction and whether or not that can happen safely, we don't have good data for that, and that's one of the things that we are most worried about in terms of space settlements.

Childbirth and rearing are two of the most uncertain aspects of a potential future human expansion past our Earth. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: Well, I don't think when we talk about going to space, a lot of people really think about like, envision kids, like young kids in space. We're always thinking about like Matt Damon and The Martian. You know, it's these adults on these settlements. But what are the considerations when it comes to kids and human pregnancy in space?

KELLY WEINERSMITH: Yeah. So we would say that the defining characteristic of a settlement is having children and like having families live out their days, and we just really don't know how that's going to go. So we have 50 years of data from space stations orbiting the Earth, but all those astronauts have been in free fall, so experiencing something like no gravity, and as far as we know, none of them have been pregnant, and only about 13% of the people who have been up there have even been women. So we don't even have a lot of data on female bodies in space. We also don't know how space radiation is going to impact these bodies. As Zach mentioned, these space stations are orbiting within the protection of the magnetosphere, so they're not experiencing space radiation. So we have very little data, but the data we do have are concerning. So we've sent rodents to space while pregnant, and when they come back, they need to do twice as many of a certain kind of contraction, and we think that's because their muscles get weak when they're not exposed to Earth gravity. So when they came back and went through labor on Earth, they had some problems.

DOERING: Oh, man.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: I know! I don't want to be in labor for twice as long, like it was already too long, twice as long.

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

KELLY WEINERSMITH: No, thank you. And so we also know that there's some hip problems. So astronauts lose about 1% of the density of their hip bones every month, and Mars, having 40% gravity might slow that down a little bit, but if, instead of like a couple months, you're now talking about years or developing under those conditions, is your hip going to hold up when labor kicks in? Unclear. It's also not clear that, like menstrual cycles work normally in lower gravity. There's all of these different stages that we don't understand well enough. And there hasn't even been a rodent colony that has had rodents born in space, impregnated in space, gone through pregnancy and had safe labors, and then started that cycle again. And so I feel like that's a minimum amount of data that we need, and you couldn't really get that information from the International Space Station. You'd have to maybe go to the moon and set up a research station there so that you're exposed to space radiation and lower but some gravity, and start to get a handle on things there.

DOERING: Wow, we're not there yet, it sounds like you're saying.

KELLY WEINERSMITH: No, no.

One proposed strategy for mimicking Earth gravity in the vacuum of space involves the use of something called a rotating wheel space station. (Image: Drawn by Zach Weinersmith)

DOERING: Well, and there are some solutions, potential solutions, that have been raised in terms of manufacturing gravity in space, Earth-level gravity in space. What do you think about those ideas? Zach?

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Yeah, yeah. So this idea actually goes back to the 1920s you know, the idea is, well, you don't have gravity, and maybe that's bad. But when, if you've ever been to that carnival ride where they spin you really fast, you know, you sort of stick to the wall. So that's what we mean by artificial gravity, is you spin, and then that centripetal force, forces you against a surface. And so that presumably would solve a lot of the classic medical problems of space, like diminished muscle and bone mass. And so why not do this? Especially because, you know, when it got big in the 70s, they started making all these cool pictures. Why not do this? Well, there are a number of reasons, but the deep problem is you have to just get mass from somewhere, like, stuff is not available in space. So if you're talking about a million tons, it would be expensive, right? This is like exploding 10,000 skyscrapers. So usually there's an alternative suggested. So they're basically two classic ideas, one of which is, go grab asteroids, which we haven't got into but, but like, basically would be we don't have the technology yet, and when we do, it will be quite expensive. And then, mind you, of course, then you have to catch the asteroid and convert it to suburbs, which is often sort of glossed over. And then you could set up what's called a mass driver. If you want to visualize a mass driver, imagine there is like a maglev train, like a train that floats on magnets, and the track goes along the lunar surface, then goes up and then just ends. And so you put a train on that with, like a cargo, it flies up and shoots its cargo into space where it's caught by literally, a sort of giant space catcher's mitt, where, again, it is somehow converted into orbital suburbs. That's hard enough. Add in that building a rotating space object is actually tricky because you're putting fairly large forces on this object. We call it the washing machine problem, which is, if you've ever, like, put towels in wrong in a washing machine, halfway through the cycle, you hear it going kachunk, kachunk, kachunk.

DOERING: Oh yeah.

ZACH WEINERSMITH: Because it's unbalanced, right? Yeah. And so this can be solved. The usual solution is something like, you have hydraulics, which you know, if everybody's on one side of the station to watch a Taylor Swift concert, you shift a bunch of water down the other side of the wheel so that it counterbalances all the Swifties. So this is doable, but you see how it's a little terrifying, and if it goes wrong, you know the concert gets opened to the void. To sum up, these are cool. They are space settlement on extreme hard mode.

Links

Purchase a copy of A City on Mars (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth