Zombie Fires in Canada

Air Date: Week of July 25, 2025

The first one right? So: Despite what the name suggests, zombie fires are not a supernatural phenomenon. Zombie fires burn for months at a time, all the way through the winter. When spring arrives, they become more apparent, seemingly coming back from the dead. (Photo: Western Arctic National Parklands, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Wildfire season has scorched nearly 14 million acres in Canada this year, degrading air quality as far downwind as Montreal, Detroit and Philadelphia. A particularly dangerous kind of wildfire, known as “zombie fire”, can survive through the winter months by smoldering underground. Professor of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University Patrick Louchouarn joined Living on Earth’s executive producer Steve Curwood to discuss this phenomenon.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Wildfire season in Canada is raging, with nearly 14 million acres in the country already scorched this year, degrading air quality as far downwind as Montreal, Detroit, and Philadelphia. While fires are a natural part of the boreal forest ecosystem, increasing global temperatures due to climate change are creating conditions that supercharge these blazes. And now scientists are investigating the potential link between climate change and a particularly threatening kind of wildfire. These are so-called “zombie fires”, or fires that can survive through the winter months by smoldering underground. Patrick Louchouarn is a Professor of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University and he joined Living on Earth host and executive producer Steve Curwood to walk us through what we are learning about this phenomenon.

CURWOOD: So, tell us, what exactly are zombie fires? How are they different from the wildfires most people might see on the news?

LOUCHOUARN: Zombie fires really are fires that live for and burn for a long time. Sometimes, some of these fires might actually catch into the soil. And when you have a lot of organic matter in the soils, and soils are dry enough, then they can actually start fires, particularly peats that dry out can burn. And then when they start burning, they can actually burn for a long time at a very slow rate. And we call them "zombie" because the fires continue burning during winter and re-emerge in the spring. So, they are kind of fires that don't die. Eventually, they die when fuel gets consumed, but they endure for a long time, much longer than what we call above-ground vegetation fires.

CURWOOD: To what extent do these zombie fires extend the fire season there in Canada? Does it mean that we see fires earlier than we might otherwise see wildfires, and might they hang around longer than they might otherwise?

Zombie fires could be a threat in areas all around the Arctic Circle. (Photo: Tom Patterson, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

LOUCHOUARN: Well, yes, when they happen, they do, because they tend to actually burn, some of them, for years, and they can actually exist and survive the winter. So, when the spring comes in, and the summer comes in, and it gets warmer again and drier again, then these ground fires can actually help in burning the surface of the vegetation.

CURWOOD: And where are we talking about here on the planet. I've mentioned, of course, Canada. But where else are these zombie fires a phenomenon?

LOUCHOUARN: Well, all around the Arctic Circle. So, of course, Siberia, which is an enormous swath of territory in northern Europe, all the northern European countries of Scandinavia, Alaska, and Canada. So, the entire Arctic circle has a very large region of land. Of course, the Arctic is an ocean, but it's surrounded by this immense amount of land that contains much more organic matter in the soil than there is in the atmosphere. So, there's a huge amount of material and organic carbon in the soils right now. Most of it is frozen, but due to the disruption of the temperature and the climate conditions in these regions, some of it is starting to dry, melt, and being released in rivers, or some of it burns.

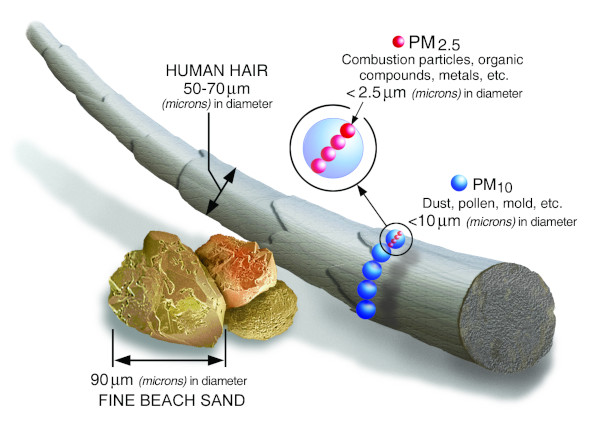

PM2.5 particulate matter is small enough that it can enter the bloodstream. (Photo: U.S. EPA Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards (OAQPS) Information Transfer Group, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: So, these underground fires that can just keep burning and burning, what might the consequences of that be?

LOUCHOUARN: Well, multiple levels. Of course, a much faster return of carbon to the atmosphere that has been trapped for a long time. So basically, a little bit analogous to when we burn fossil fuels. So that's organic matter that is right now sequestered, not available to get back into the cycle of carbon in the earth. If it returns to the atmosphere, it contributes to the radiation balance of the Earth. More CO₂ creates more greenhouse effect. So that's one impact. The second one is, of course, particles. These fires are much less efficient than surface fires because there is a very low proportion of oxygen, so the burning is at a lower temperature. There's a lot of combustion that emits CO₂, but not just CO₂, a lot of particles and other gases. More particles tend to be transported long distances, especially because they're micro particles, long distance due to wind patterns. So, we're going to start seeing more and more air quality decreases and contamination and transport in areas of high population, because we tend to have very large cities in the northern hemisphere that will be affected by the transport of particulate organic matter.

CURWOOD: You're talking about public health problems.

Wildfires can affect the air quality of areas thousands of miles away. Above, New York City experiences significant wildfire smoke from Canadian wildfires in 2023. (Photo: Metropolitan Transportation Authority from United States of America, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

LOUCHOUARN: Absolutely. And I gave a lecture not too long ago, and basically, I said that wildfires are no longer a local problem. At best, they are regional or pan-regional problems. They could be hemispheric problems if you know, you have very large swaths of the northern hemisphere that starts burning every summer season, that releases particles. And we've seen that in 2023, there was a huge amount of those particles that reached both from Central northern United States and Canada all the way to the eastern seaboard. And I was at a conference in Philadelphia, and it was interesting, because we were asked not to leave the hotel. And now it was kind of my worst nightmare. I work on this phenomenon, and suddenly I realized, oh boy, I thought we were several decades away from starting to see this happen, and we even saw it a little earlier this year in the central US states as well. So more and more of that will actually lead to impact to health, particularly for the elderly, the young, individuals who have issues, you know, respiratory vulnerabilities. We will see more and more of this impact at a regional to pan-regional level.

CURWOOD: Why is it harder for firefighters and first responders to tame and extinguish these zombie fires? What's the physics of that? Why can't they do it?

LOUCHOUARN: First of all, there's the remoteness of it. You have to get to these fires. We have to remember that on the northern regions of the Northern Hemisphere are sparsely populated. Just getting to some of these places is really not easy, supporting firefighters to be in those places. The second piece, the physics of it, if they happen underground, it's really hard both to locate where those fires are. You can see some smoke coming out, but it's not as if, when you see surface fires, you have flames, you have vegetation, house burns, you can actually douse them. Really hard to douse these fires, they smolder, so they take a whole lot more effort to extinguish. And then the last piece is, it is dangerous because you have to be on a soil that is burning underneath. So there are some instabilities in the soil. Even bringing machinery could be dangerous because the soil could cave. There are a lot of physical constraints that create real difficulty in addressing them.

CURWOOD: What relationship is there to climate disruption and this phenomenon of perhaps more zombie fires? What's the connection, if any?

Zombie fires are far more difficult for firefighters to manage than above ground vegetation fires, like the prescribed fire pictured above. Zombie fires are much harder to see. They also make the ground itself unstable, creating a safety hazard. (Photo: Neal Herbert, Department of the Interior, RawPixel, public domain)

LOUCHOUARN: I really appreciate that you use the word climate disruption, because I think this is an important note that climate change normally in some, that change can happen very quickly, particularly for the northern hemisphere this is really important. The Arctic region of the Earth in the northern hemisphere is changing, and has changed at a much higher rate in terms of temperature than other parts of the Earth. That has led to a lot of different changes. Some of those changes lead to more storms, that lead to more fires themselves. There are changes in the hydrological cycles, more drying of the vegetation, and in particular, more drying. And this is the part that actually relates to your question, more drying of the surface soils, more melting of permafrost. And permafrost is very deep organic soils that, of course, as the name implies, they're frozen, but when they actually dry out and melt, that water can actually seep out and the soil can dry, especially under hotter conditions, and that becomes a very available fuel to start burning in smoldering conditions. So, the more we see changes in the upper latitude of the earth in areas that contain an enormous amount of organic matter in soils, then, what happens is you have the potential for that material to become fuel for burning, and especially when they dry.

CURWOOD: What do we know about the frequency of these fires and the trend that's going on?

LOUCHOUARN: Not much. I'll be honest with you. We know they exist. We have a number of examples of how extensive they can be. We don't have much of a way to measure trends. And so one of the things that we do to measure wildfires is we can use satellite and remote sensing imagery, and we can actually—there are ways to calculate how we, you know, fires that exist above ground, and calculate their extent. So, there are a number of ways we can actually start looking on the trends of surface fires. For ground fires, it's really difficult, we haven't actually cracked—there are some studies at the moment, are starting to try to use satellite imagery in terms of differences in temperature of the soil, smoke plumes, to try to identify potentially ground fires. But that's a very difficult one yet and hasn't been resolved. We don't know that there is a trend for an increase in extent and severity of these soil fires at the moment, but I'm not sure we can actually talk of trends. What we can talk about is the potential for the increase both in extent, severity and frequency. But at the moment, we don't have the data, as far as I know, to demonstrate that this is happening. But my sense is that I wouldn't be surprised if you know within the next ten years, and definitely twenty, we see more of those, and the smoke plume events start reaching lower latitudes because of the wind patterns, whether it's in northern United States or it's in northern Europe and Russia we'll start seeing more and more of these events.

Louchouarn suggests that public officials set up shelters, like those for other natural disasters, during periods of poor air quality to protect those with preexisting conditions. (Photo: Andrea Booher, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Picryl, public domain)

CURWOOD: So how concerned are you about this phenomenon, about this likely increase in these so-called "zombie," these ground fires that can put out such toxic levels of particulates?

LOUCHOUARN: Well, I'm very concerned. You know, it was really interesting, because I was, as I mentioned, you know, my Philadelphia experience, you couldn't walk outside. You know, and I consider myself to be healthy. I don't have any respiratory illness, and it was very difficult to be outside for an extended period of time. So, we're going to start seeing millions and millions of people being affected by these haze event that leads to morbidity and mortality. Morbidity being increased levels of illness, mortality, of course, is, you know, death. So I'm concerned that we don't understand that the increase of wildfires, whether they're above ground or below ground, lead to an increased level of particulate matter into the atmosphere that leads to massive public health events that limit life expectancy, affect a number of individuals across the board.

CURWOOD: So, let's follow it up a moment. I'm a public health official in Philadelphia, let's say. What the heck can I do to deal with these plumes of smoke, especially the particulates in them from these zombie fires from hundreds of miles away, even more than 1000 miles away?

LOUCHOUARN: Well, that's a super good question. Well, there are a couple of things that we can do, but were you and I be you know, public health officials in Philadelphia, I think that the most important thing is good information to the citizenry on what that means in terms of potential impact to individuals that are most at risk, and having a clear communication accessible to all. Not everybody has access to information, so making sure that you know people have the possibility of understanding what's happening, opening shelters to offer protection, air quality protection, that is, you know, where air is filtered. In the same way that we start thinking of shelters post-hurricanes or any other type of hazards, we have to start thinking of those as very large-scale hazards that affect thousands, if not millions, of individuals. Then the second piece that has started to happen in 2023 is starting to understand that although these fires are remote, as a matter of fact, the fires that affect our regions or in another country, is understanding that, if not a responsibility, but we have a certain potential commitment to deal with those and abate those fires. So, sending resources, machinery, firemen, firewomen, individuals who are supporting the fight against these fires, and understanding that because this is affecting our population, we may be part of the solution, right? And so now more and more, we're starting to see these compacts of firefighter support, even if they're remote in other regions.

CURWOOD: So you're a scientist, and scientists, of course, often are involved in public policy discussions, sometimes with comfort, sometimes without comfort. In this case, as a scientist and as a human here, what gives you hope, understanding what's going on with these zombie fires?

Patrick Louchouarn is a professor at Ohio State University. (Photo: Courtesy of Patrick Louchouarn)

LOUCHOUARN: Oh, well, I might be biased in the sense that I always have hope, and I have an incredible faith in the human creativity and possibilities. So, I think that one of the things that's important is for us scientists to communicate more clearly of, A) What is it we're observing? How much do we know? What remains to know?—This is why I said I have to be really careful, because there are certain things we still don't know about—These zombie fires exist, but is there a trend in increasing, I don't know. What do we see in the future and communicate in the more accessible way so a lot of people understand, particularly, and your question to being a public official, public health official, is really important. Then, what can we do? What are the mitigation factors that we can put into place? And it could be that we can't avoid a catastrophe, but we can mitigate it and we can remediate it, and that's really important to understand that on there are different groups of humans that are impacted in different ways, both of their health, in terms of access to resources, and how they actually, where they live. So, we have to start understanding that we have a responsibility to all, and that's where I stop being a scientist and more of a human and trying to understand, how does my work and my understanding plays out in public environment and public health decisions?

O’NEILL: That’s Patrick Louchouarn, Professor of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University, speaking with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Links

Popular Mechanics |"Hot New Environmental Threat: Zombie Fires That Come Back to Life"

BBC | "What Are Zombie Fires?"

Learn more about Dr. Patrick Louchouarn

Read Dr. Louchouarn’s article on zombie fires in “The Conversation”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth