CO2 Pipeline Safety Risks

Air Date: Week of March 3, 2023

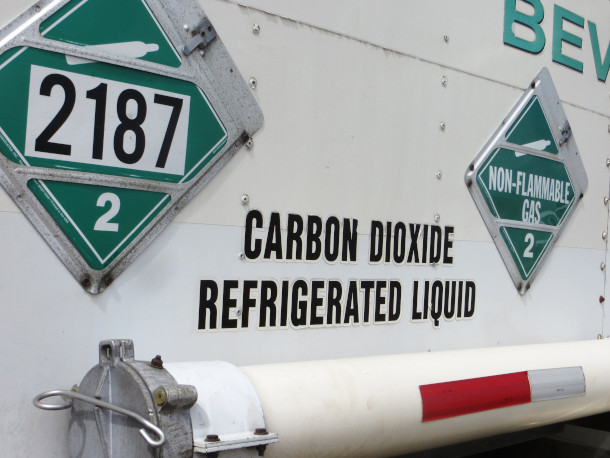

Refrigerated carbon dioxide used in firefighting. Carbon dioxide can be transported in a gaseous, liquid, or supercritical state. (Photo: Washington State Department of Ecology, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Proponents of carbon capture and storage hope to expand a network of pipelines that transport carbon dioxide from source to sink so that it can’t get into the atmosphere to warm the planet. But these pipelines carry high-pressure CO2 that can be dangerous, even lethal. Bill Caram, the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, explains these safety concerns.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Before the break we talked about the unfolding hazards of transporting toxic chemicals via train. Pipelines can also be a source of spills for everything from oil and natural gas to carbon dioxide from carbon capture and storage technology. Carbon capture and storage has long been a hope of fossil fuel companies and carbon heavy industries like power plants and factories. It allows industry to emit carbon dioxide, business as usual, and safely store it below ground where it can’t warm the planet as a greenhouse gas. Proponents see carbon capture and storage as another tool in the fight against climate change but critics say it’s a relatively new technology with a lot of unknowns. And it’s expensive though tax incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan Infrastructure Bill could make carbon capture and storage more economically feasible. Another concern is safety, especially when it comes to pipelines transporting carbon dioxide from where it is produced to where it will be stored. For more I’m joined now by Bill Caram, the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust. Welcome to Living on Earth, Bill!

CARAM: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So what exactly is the carbon dioxide that would be moving through these pipelines? Can you describe what state it's in?

CARAM: Yeah. If everyone remembers back from high school science class, you can have a gaseous state, you can have a liquid state, you can have a solid state. CO2, carbon dioxide, can be moved in a gaseous or a liquid state. What maybe you didn't cover in your high school science class, there's another phase called a supercritical fluid. And that is actually where carbon dioxide is regulated, and is often moved through pipelines.

DOERING: So when we talk about oil and gas pipelines, you know, we worry about these images when a horrific accident happens and there's a pipeline rupture, and we might see the oil spilling out, you know, maybe there's even flames. It's very visible, it's very obvious the damage to the environment from that. But we're talking about moving CO2 and I'm wondering about the dangers there. You know, maybe they're not quite as obviously visible in photos, but what could happen if we're moving CO2 through pipelines like this?

Site of the pipeline rupture in Satartia, Mississippi. Fifty of the town’s two hundred residents sought medical attention after their exposure to the carbon dioxide that was released. (Photo: Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, PHMSA.gov)

CARAM: CO2 really is its own set of risks. It's really unique. It's not going to explode, there's a little bit of risk to water, but not in the way that the hydrocarbons have. And its threat is as an asphyxiant. It displaces oxygen. CO2 is heavier than air. So methane is lighter than air, and so when a natural gas pipeline ruptures, the methane will dissipate, whereas CO2 will sink and stay close to the ground. And because they're often moved in this high pressure, dense phase, you can have a lot of CO2 emptying a pipeline all at once in a rupture. And that can lead to this dense cloud staying close to the ground and migrating in the direction of a light wind or going downhill along the topography of an area. And it can settle in low lying areas at dangerous and even lethal concentrations.

DOERING: Tell me more about that. What does that mean, potentially, if there's a village or homes in a low valley where the CO2 sinks down and collects?

CARAM: So we saw this happen in a community called Satartia Mississippi in 2020. A pipeline that ran near that community carrying CO2–by Denbury–there was a landslide and the pipeline ruptured. The valves are 20 miles apart, 10 miles apart. And so all of that CO2 comes out of the pipeline. And it's odorless and invisible. It slowly made its way to the community of Satartia. Now, the operator, they thought that the community was far enough away from the pipeline that it would never be an issue and so it wasn't part of their, you know, emergency response plans. They didn't consider it a high consequence area of the pipeline. But it did, in fact, reach the community and it sent 50 people to the hospital. The community is only 200 people. Some were very sick. It's amazing that nobody died. The first responders were true heroes. They donned scuba gear, they didn't really know what was happening. But they figured out they needed scuba gear. Their cars weren't operating because there wasn't enough oxygen for their internal combustion engines.

Lake Nyos in Cameroon, Africa. A natural release of CO2 gas from the lake killed 1,700 people living in the low-lying area nearby. (Photo: jbdodane, Flickr, CC BY–NC 2.0)

DOERING: Oh my gosh.

CARAM: So they put on scuba gear, and they kind of ran into this white cloud. And we're pulling people out who had, you know, were walking in circles, were having seizures, all of these signs of this high CO2 exposure. So we had 50 people go to the hospital. The hospital didn't really know what to do with them, sent them home. A lot of them came back the next day, and they finally did some blood work and they just had these super high levels of CO2 in their blood. We're now three years later and there's still some folks that are feeling the effects of that today.

DOERING: Are there any other examples of instances where CO2 leaked and people did perish?

CARAM: So in the 80s there was a large natural release of CO2 from a lake in Cameroon, Africa, and it killed every oxygen breathing person and animal within 16 miles of the lake in kind of a circle around it and it ended up being 1,700 people died. And that's when the United States Congress told the federal regulator of pipelines, "Hey, you need to start regulating CO2 pipelines." To be clear, the amount of CO2 they've estimated that is much larger than would come out of any kind of pipeline failure at the types of pipelines we're talking about in the US.

DOERING: But what kinds of carbon dioxide pipeline projects are currently proposed in the US?

CARAM: So there are a number of projects that are proposed. Currently, there are a number of projects announced in the Midwest that would capture CO2 from ethanol production facilities and move them to various sequestration sites in the upper Midwest. Ethanol is kind of a low hanging fruit for carbon capture and sequestration. It's relatively inexpensive to capture CO2 from those facilities and it ends up being relatively clean carbon dioxide without a lot of impurities. We also have of a project further west that is looking at converting an existing pipeline to carry CO2 to a sequestration site. There's also a number of projects announced down in the Gulf states where they would be sequestering CO2 in the Gulf of Mexico and under–under the sea floor. And as we move away from ethanol and into, you know, power plants and things like that, impurities in the CO2 are going to become much more of an issue. So right now we have about 5,000 miles of CO2 pipelines. They're in really rural areas. The roadmap looks like we're talking 100,000 miles or considerably more. I fear they will be much closer to people's homes and closer to communities than they are right now.

The Petra Nova carbon capture system in Texas. Pipelines move the CO2 collected at carbon capture sites to facilities where it can be used. (Photo: US DOE, energy.gov, public domain)

DOERING: Are these pipelines above ground, underground? What are we talking about here?

CARAM: They are buried. Depends on a lot of variables in the regulations, but you know, three to five feet below ground. The fact that it's buried doesn't necessarily make it safer, although it does keep it from maybe some excavation damage or, or somebody driving into it in a car accident and protects it that way. But in the case of a rupture, you know, whether it's buried three feet or five feet, it's going to be a pretty violent rupture.

DOERING: So you mentioned that in this Satartia incident that happened a couple years ago, it wasn't really clear the risks to the community of Satartia, if there was going to be a pipeline leak. Why is that? And how good is the modeling in terms of like, you know, if a pipeline breaks at this particular point, and it's carrying CO2, what the impact could be.

CARAM: So we have pretty good models and formulas to figure out the potential impact radius, the area around the pipeline that would be impacted by a failure, for hydrocarbon pipelines, for oil and gas pipelines. Because CO2 is heavier than air and it doesn't ignite, it can move kind of long distances away from the pipeline in kind of unpredictable ways at these dangerous and lethal concentrations. And so how do we figure out which pipelines have the potential to impact a community? There's a lot of work to be done in this area. We don't have a model that we can just point to and say, "Use that model, run it on your whole pipeline and see where it could impact communities." There's a lot of R&D being done on that right now but it's an unanswered question of the best way to do it. And this is important because once an area of a pipeline is determined to have the ability to impact a community, the operator has higher safety standards for that section of pipeline. More inspections, you know, higher quality of pipe. And so if we're not measuring that properly, we can have long sections of pipe that might impact a community that aren't being inspected as often as they should and aren't built to the high specifications they should. It's definitely one of those things that keeps me up at night about these new CO2 pipelines.

DOT office in Washington, DC. PHMSA, one of the Department of Transportation’s operating bodies, is responsible for regulating hazardous materials transportation (Photo: D Ramey Logan, US Department of Transportation, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DOERING: What's the top line concern here for your group, for the Pipeline Safety Trust?

CARAM: Our main concern is that the regulations are really far behind. The federal regulator is PHMSA, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, is part of the Department of Transportation. And when Congress asked them to start regulating CO2 pipelines in the 80s, you know, knowing that there were so few miles and that they were relatively rural, they just kind of added "and CO2" on to the existing hazardous liquid pipeline regulations. And CO2 poses unique risks and it requires unique regulations. And we don't have those. And we have kind of big regulatory gaps. So right now, it's only regulated if it's a supercritical fluid, that unique high pressure, high temperature state if it's a liquid, or if it's a gas it's not regulated at all. We don't have any regulations around adding an odorant so that people would know when there's been a release. So a lot of people don't know this, but natural gas has an odorant added to it so that you get that rotten egg smell. You wouldn't smell it otherwise. And so we would love to see an odorant added so communities will know when there's been a CO2 release. There's also a lot of issues around impurities in CO2. Even just having water in CO2 leads to carbonic acid, which just eats through steel pipelines. The natural sources where operators are getting the CO2 from now is very dry. But when we start getting it from these other sources like power plants, they are going to start having a lot of impurities and we're going to have to deal with corrosion in a way that the operators aren't used to right now on CO2 pipelines, and the regulations just don't cover it at all. One interesting thing about these pipelines: a natural gas pipeline needs to go to a federal agency for approval of the siting of the pipeline, the route that it takes. There is not that requirement for any liquid line, including a CO2 pipeline. Each state has its own rules, so these local governments and state governments because PHMSA regulates the safety, they can't make safety–kind of–any part of their permit. They can't say,

DOERING: Oh wow.

CARAM: Well, it's not safe to be that close to a school," or "You have to show us what kind of safety precautions you're taking if you're going to be that close to a school. They're preempted from being able to do that.

DOERING: That's incredible. What you're describing is that, just the system of regulation that we've created leaves really huge gaps in some areas. So can you clarify for me, what are the regulations right now about, say, distance from a school?

“A PST report identified regulatory gaps and dozens of groups [then] asked the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration to pause carbon capture permits until new, federal safety regulations are created." https://t.co/Z7UplmpDkA

— Pipeline Safety Trust (@pstrust) January 26, 2023

CARAM: There are none. You know, the operator has a certain distance around their right of way, but there's no law that says you can't build, you know, right up to a, a pipeline to the right of way.

DOERING: Wow. It makes me wonder, you know, if–if some of the same regulators are involved in regulating railroads, and we've seen what just happened recently in East Palestine and how potentially a lack of appropriate regulations or oversight may have contributed to that, makes me a little concerned about what could happen with pipelines, including carbon dioxide pipelines.

CARAM: It's a fair concern and it's one that I share with you. These regulatory bodies, they are passionate about their jobs and they want to keep people safe. But they're understaffed and they're underfunded and they really don't have the resources they need to appropriately regulate their industries. And so what they're kind of forced to do is rely on the industry for their technical expertise and helping them write the regulations.

DOERING: And what have you heard from PHMSA and DOT about the possibility of putting in place some of these regulations?

CARAM: Well we were really thrilled to hear PHMSA announce last May that they are undertaking a rulemaking, meaning that they are going to put in place new regulations on these pipelines. We don't know how long that will take. It's generally a multiple year process. And we really don't know how comprehensive those rules will be. And we certainly hope that they address all of the shortcomings that we've identified.

DOERING: Bill Caram is the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust. Thank you so much, Bill.

CARAM: Thank you, Jenni.

Links

Huffington Post | “The Gassing of Satartia”

Click here to read reports and fact sheets from the Pipeline Safety Trust about CO2 pipelines

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth