Malaria Vaccine Gets Green Light

Air Date: Week of November 12, 2021

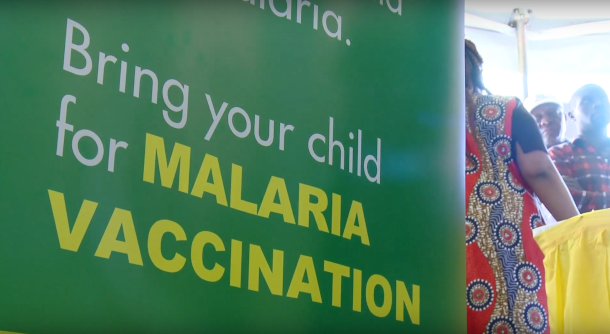

The World Health Organization has announced their recommendation of the RTS,S malaria vaccine. (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Malaria is responsible for almost a half-million deaths every year, many of them among children. Researchers have been working on developing a malaria vaccine for nearly a half century, and at last the World Health Organization has given its first-ever stamp of approval to a malaria vaccine. Immunologist Dyann Wirth of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health joins Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill for more.

Transcript

CURWOOD: A big risk for people living in or even visiting in the tropics is malaria. Fever, shaking, chills and excruciating pain are hallmarks of this tropical disease that is also found in some primates and transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. Malaria infects more than 200 million people every year around the world, kills about 400,000, and half of these victims are children in Africa. After nearly fifty years of research scientists have finally developed a vaccine for malaria that has won the first-ever approval by the World Health Organization. This first vaccine is considered to be about 40 percent effective, and while it is less than perfect and requires boosters, it is being heralded and deployed, as it is better than nothing to help human immune systems ward off malaria, even as efforts continue to develop even more effective vaccines. Dyann Wirth is an immunologist and Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She spoke with Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill.

O'NEILL: Please briefly remind our listeners as to what malaria is and how we currently treat the disease.

WIRTH: Malaria is an infectious disease. It's caused by a microorganism that is carried by mosquitoes. And the disease that we know of as malaria, primarily, the symptoms are caused by the result of the parasite infecting the human's red blood cells. And the disease can be very severe, it can lead to coma and death, that could happen to anyone. But the burden of the disease is primarily in young children in Africa. So once the parasite has successfully infected the individual, that individual then can serve as a source of infection for new mosquitoes when they feed on the person, so then the cycle continues. Unlike many of the infectious diseases we've been hearing about recently, the COVID virus, for example, which is transmitted through airborne from person to person, this disease requires the mosquito as an intermediate host.

There are about 100 species of mosquito that can transmit human malaria. Mosquitos are responsible for more human deaths than any other animal on the planet. (Photo: Ryszard, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: How is the world faring right now in the fight against malaria?

WIRTH: In many ways the world is making progress. In the first half of this century, we have seen reductions in overall burden of disease and reductions in death. And in some countries, we've actually seen malaria completely eliminated from those countries and WHO has declared countries as certified as malaria free. But in sub-Saharan Africa, progress over the first 15 years of this century was really quite successful, there was a reduction in overall malaria cases, and importantly, a reduction in the number of deaths. However, starting in around 2015, progress seemed to stall. Now, it's important when we say stall, that is the number of cases now and in 2015, are quite similar, and the number of deaths are quite similar. But that's of course, in a background of a growing population in sub-Saharan Africa. So, the current measures are still reducing malaria burden, but we're not making progress toward eliminating the disease, particularly in the high burden countries in Africa.

O'NEILL: Can you tell us a little bit more about this vaccine that's just been recommended by the World Health Organization?

A child dies from #malaria every two minutes.

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) October 6, 2021

One death is one too many.

???? Today, WHO recommends RTS,S, a groundbreaking malaria vaccine, to reduce child illness & deaths in areas with moderate and high malaria transmission https://t.co/xSk58nTIV1#VaccinesWork pic.twitter.com/mSECLtRhQs

WIRTH: This is the first ever vaccine for a human parasitic disease. Parasites are very complicated organisms, they have 5000 genes compared to say, a virus that has 10 or 20 genes. And it's been very hard to create vaccines that are able to impact the parasite's infection, or its ability to cause disease. So, this is a very exciting development.

O’NEILL: And what have been some of the steps in getting this vaccine developed and then approved?

WIRTH: It has been over 30, even 40 years in development, this particular vaccine, and it has gone through both standard clinical trials, both phase one, phase two and phase three clinical trials. The phase three clinical trial was in about 16,000 children in 11 sites in seven countries in Africa. And after the conclusion of this trial, there was a positive recommendation by the European Medicines Authority for the vaccine. However, the World Health Organization wanted to first test the feasibility of implementing this vaccine on a broad scale in Africa, particularly to children, the most susceptible group, and so the result of these implementation trials was the vaccine is indeed safe. Those safety signals seen in the phase three trial were by chance. It is feasible, the vaccine was implemented using an existing vaccine delivery program called the Expanded Program in Immunization, or the EPI program, which is implemented across the African continent and reaches very high levels of coverage, especially for a recently introduced vaccine. And the impact of vaccinating children was the overall 30% reduction in hospitalizations due to severe malaria, a reduction and, although the implementation studies didn't look at vaccine efficacy directly, there were reduced numbers of malaria cases in those children vaccinated. So the recommendation by the top committees at WHO that consider vaccines, and consider the malaria program and policies around malaria was in fact, to recommend the vaccine for broader use. Clearly, the vaccine is not ideal. It doesn't completely prevent infection, and it requires multiple doses. However, it is a completely different mechanism of preventing disease than existing measures, which include controlling the vector, so reduce essentially the mosquito's ability to get to and bite individuals, and diagnosis and treatment of clinical malaria, also very important in reducing disease burden, but different mechanisms. A vaccine actually teaches the human immune system to recognize the parasite as it enters the body and attack it. After vaccination, the person is poised to respond to infection rapidly, and thereby prevent the disease from manifesting itself.

A poster advertises a malaria vaccine clinic from a trial program in 2019. (Photo: GHTC, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

O'NEILL: Now, what issues, if any, might we see with the rollout of the vaccine now that it has been approved?

WIRTH: Well, I think one of the main issues of course, there's a lot of excitement, everyone will want the vaccine but in the first years, the supply will be limited because of course, until the vaccine was approved, the company and those providing funding for the vaccine weren't ready to make the investment. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations is the funding agency for vaccine purchase for many of the countries where malaria is endemic. So, the GAVI board now that WHO has made the recommendation, this will go before the GAVI board, and they will make a determination about whether or not they will invest in purchasing doses of the vaccine for countries to use. This is a very important step and it's not necessarily a foregone conclusion that GAVI will approve this. So, I think it's very important at this point, that countries and populations who want this vaccine let their views be known. GAVI has a broad base board, including board members from disease endemic countries, and I think it will be important to listen to those voices. But the vaccine interest and uptake among the families who were part of this 800,000 children in the implementation pilots were very enthusiastic about this opportunity for their children.

O'NEILL: What does this vaccine mean for other malaria vaccines and mean for vaccine science in general?

WIRTH: This work has proved that a vaccine for malaria is possible. There were many who didn't believe it was possible. And this also opens the door for innovation. We're already seeing potential new uses of this vaccine in preventing the major peak or seasonal peak of malaria infection in young children by providing a booster shot to those already vaccinated to give them a little extra protection during the peak of malaria transmission. There will need to be more evidence for final kind of regulatory recommendation, but its data is accumulating that this is a very clever use.

Immunologist Dyann Wirth is the Richard Pearson Strong Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: Courtesy of Harvard T.H. School of Public Health)

There are other vaccines that are in the pipeline for development, some that are based on the same actual antigen molecule, but different formulations and presentations, which are in clinical trials. There's a whole cell vaccine. And excitingly, we heard very recently that the group in Germany, the company in Germany, BioNTech, that has been involved in the breakthrough COVID vaccine, actually is taking on a development project to develop an RNA-based malaria vaccine. Again, these are innovations. We don't know if they're going to work. But I think this gives a kind of validity to this strategy. And one that I think is, is both exciting, and I think will allow the scientific community to begin to imagine making even better vaccines. This first one is a groundbreaker. And it's, it's very important to say here that this represents years of work. It takes a village to raise the child. It takes a super village to make a vaccine.

CURWOOD: Dyann Wirth is an immunologist and Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neil.

Links

World Health Organization | “WHO Recommends Groundbreaking Malaria Vaccine for Children at Risk”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth