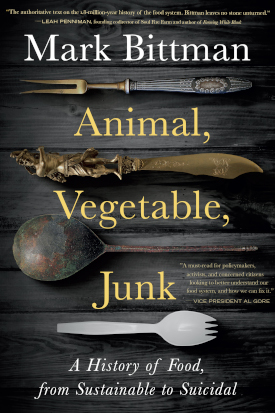

“Animal, Vegetable Junk”

Air Date: Week of May 28, 2021

Mark Bittman defines junk food as just about any food that didn’t exist before the 20th century. (Photo: Tracy Benjamin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Few things are more important to our survival than food, but access to fresh, healthy food has become a luxury for many on the planet, and the food many of us eat contains more meat and sugar than at any point in human history. This history is the subject of a new book by New York Times columnist and cookbook author Mark Bittman called “Animal, Vegetable, Junk: A History of Food from Sustainable to Suicidal.” Bittman joins Host Steve Curwood at an online Living on Earth Book Club event to talk about the origins of our industrial agricultural system and how we can strive for a better future.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Few things are more important to our survival than food, but today's food system often bears little resemblance to that of our ancestors. Access to fresh, healthy food has become a luxury for many on the planet. And the food many of us eat contains more meat and sugar than at any point in human history. Industrial agriculture is the subject of a new book by New York Times columnist and cookbook author Mark Bittman. His book is called "Animal, Vegetable Junk: The History of Food from Sustainable to Suicidal." It looks into the origins of our Western food system and ways to have healthier food. Mark Bittman joined us as part of our Living on Earth Book Club live event series, and to start our conversation I asked him why he says social stratification in human society largely began with the advent of agriculture:

BITTMAN: Before there was agriculture, there was very little, if any social stratification and even if there was, it was because I was tougher than you. It wasn't an inherited wealth, it wasn't inherited social stature. Once there was agriculture, people could start accumulating surplus. Once people started accumulating surplus, they could become traders, they could become business people, there became a society where not everybody was a farmer and social stratification began. Fast forward, say 9,500 years out of the 10,000 years we're talking about. I mean fast forward to say the middle ages or 1,500 or so. Land started to be used for cash crops and nobleman, and they were mostly men started taking land away from peasants and dictating to peasants what they could grow. And say, we want you to grow things we can sell, and here you can have this little plot of land on the side, we hope you can sustain you and your family on that. And food began to be traded. We saw the rise of capitalism and later industrialization, we saw the rise of commodity crops, which meant that food was being grown not to nourish people, not to feed farmers and their families and their neighbors and their areas, but to be sold. And what ultimately developed, where we're at now, is a system where everybody is supposed to grow as much as they can of what they grow well. So we, the United States grows, corn and soybeans and animal products well. We do that, we sell it on the open market, we get cash, we buy food, from wherever else it's from, presumably from places that grow it well. This is sort of theoretically, I mean, this is neoliberalism really, you do what you do best.

CURWOOD: Mark, you're trying to sell me this, but you don't believe this.

BITTMAN: No, I don't believe that this is the way it ought to work. But this is the way that it is working.

Wheat is one of the most abundant commodity crops in the U.S. (Photo: Georginchen, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah.

BITTMAN: This is the way that it's developed. I'm not saying this is a good thing. This is where we're at. We've lost the ability to sustain ourselves. As the early days of COVID showed we've we've lost the ability to sustain our regions. And I think one of the benefits of COVID, or one of the upsides of COVID is that we've seen the importance of regional agriculture, of local agriculture. CSAs are selling out, farmers markets are crowded, and so on, because people understand that local food, local food systems are something we can rely upon if we encourage their growth. So it's a, you know, it's a mouthful, it's a lot to say.

CURWOOD: Well, it is. But you know, one way to read this book, actually is as a critique of capitalism, and classism. In other words, you write at one point, food security isn't an agricultural issue. It's a political one. Hunger isn't a symptom of non-production. It's a symptom of inequality, of abuse of power, and wealth. Explain what you mean here.

BITTMAN: I mean, there are no hungry people with money. It's pretty simple, really, you know, you will say, you think of the poorest country you can think of or the poorest place on Earth, or whatever it is. If I send you there with 500 bucks, you'll eat just fine. I mean, this is about power. This is about equality. This is, hunger is about money. And, what's happening now is that the United States and joined by multinational corporations from around the world would like the whole world to enter into that kind of market that I was talking about before where no one grows crops for themselves, their family, their area. Everyone grows crops to sell on the world market. That is not a sustainable system.

CURWOOD: I mean, one of the parts of your book, as you critique capitalism, you point out that at its heart, economic growth, and the capitalistic system that we have right now is predicated on ever growing, but at the end of the day, that's not realistic. You can't keep expanding and expanding on a finite planet.

BITTMAN: Right? You know, what is it? Neither matter nor energy can be created or destroyed. There's only a finite amount of stuff. So, permanent growth is, it's a myth. It's a very pleasant myth. If we keep growing, then everybody will eventually prosper. But we can't keep growing. There's a limited amount of land. We've reached the limit of arable land. There's a limited amount of resources: potassium, phosphorus, nit--well, nitrogen is virtually unlimited--but we have to figure out, it's not just in food, obviously, it's in many walks of life. We have to figure out how to be sustainable, how this race, how we can endure as a big family of, let's say, a stable seven to ten billion person family. It's not going to get bigger than that. But we can support that number of people on this Earth if we're smart. If we believe in permanent growth, everybody just gets more and more and more, then we can't.

CURWOOD: I think the food system believes in permanent growth of people's waistlines, especially in the ghetto. Because you point out that at one point, the Small Business Administration was willing to lend in Brown and Black neighborhoods, but they lent for, and I'll let you finish.

Henry Heinz was instrumental in the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the first food labeling law in the United States. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BITTMAN: They went for the development of fast food and of course, gas stations. Gas stations are very important. But yeah, the SBA, very cynically said, we're going to help inner city, people, codeword for Black and Brown people. We're going to help inner city people develop businesses, but the kind of business we're going to encourage are Burger King and McDonald's essentially, which was what was around in the 70s and 80s. And this happened simultaneously with those fast food companies realizing that business by foot was just as good if not better than business by car.

CURWOOD: And they have what you call UPF, ultra-processed foods, which are addictive, right? I mean, the flavor-meisters make things like the potato chip, the fried chicken that you get at fast food, the burgers, they're loaded with chemicals that have been developed in laboratories, to addict us to them.

BITTMAN: Yeah, I mean, UPF, ultra-processed food is becoming sort of the catch word for junk, the kind of more formal catch word for junk. And one way to define junk food really is that it doesn't exist in nature and didn't exist before the 20th century. That's one easy way to look at it. Michael Moss, a former colleague of mine from the Times, his new book is called Hooked. And it is a study of the addiction of the addictive qualities of ultra-processed foods, how food engineers, psychologists and marketers have banded together to make ultra-processed foods literally addictive, if not on the same level as caffeine, heroin and nicotine, very, very close to that. As anyone who's tried to stop eating sugar can tell you, there is a physical craving when you try to stop eating sugar. I mean, you will feel it. It's not an easy thing to do.

CURWOOD: There's an anecdote in here about Mr. Heinz, Henry Heinz, you know, the ketchup, dude. What was his role in changing the future of processed foods in this country? And how are we living with those decisions today?

BITTMAN: It's funny, Henry Heinz was in part instrumental in getting the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 passed, which was our first food labeling law. And he did that by taking a chemical called sodium benzoate out of ketchup and in part substituting sugar for that. But the point was that he gained a competitive advantage by doing that, and by then questioning why there was sodium benzoate in all of his competitors' ketchups, while helping the US, the federal government, pass a law that said, you had to disclose all your ingredients on your label, including sodium benzoate, obviously. Sodium benzoate, it turns out is harmless. But that's, besides the point.

CURWOOD: A little less addictive than sugar as well, right?

Mark Bittman is hopeful that farmers markets could become a key element of a decentralized agricultural system. (Photo: Gemma Billings, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BITTMAN: Less harmful than sugar too. But ever since then, manufacturers have manipulated the labeling laws and manipulated government attempts to try to limit damaging aspects of food. And we see that every time, every time the government makes nutritional recommendations, eat less fat, eat more fiber, and so on. We see labeling that is, this food is low fat, or this food is high fiber. The point is not whether manufacturers can take out or put in the undesirable or more desirable ingredients. The point is, manufacturers have no interest in providing us with real food. They have interest in providing us with value-added food that's been manipulated and hyper-processed, and so on. And they can do that to almost any nutritional standard that the government chooses to name. So until the government recognizes that this begins, until we recognize and force the government to act on the notion that this begins with agriculture, this begins with growing real food. This begins with growing food to eat, as opposed food to hyper process and turn into things that aren't recognizable as food. Until, then we're going to have a sick food system, we're going to have a system that engenders chronic disease and ultimately causes premature death.

CURWOOD: Yes. You know, early on in your book, you point out that as societies made the transition into ag, people literally became shorter and less, less healthy. You want to talk a little bit about that? I mean, since we're all in this together, we look around and we see everybody looks about the same and everything. But actually, there's been quite a difference over the years.

Mark Bittman’s latest book is a chronological account of our global food systems and what we can learn about it. (Photo: Courtesy of Mark Bittman)

BITTMAN: There were a number of turning points in the course of history that if people knew, then what we know now might have gone differently. And there's an argument, Jared Diamond put it forward first, I think. And that argument is that the development of agriculture could be seen as a mistake because it and there's evidence, as as you just said, that hunter and gatherers were much healthier, much stronger than every generation of humans until about the 20th century. So but, you know, here's the thing. We know that we've made mistakes in history, and we know that we can't go back and fix them. What we can do is try to make those mistakes right. And what we can do is use the knowledge that we have now to try to do things better going forward. We have way more knowledge than we've ever had. Do we have the political will do we have the intent, to try to do things right, to try to work together as a community, to try to structure food so that it's affordable and available and accessible to everybody, not just to people with lots of money, to try to structure agriculture so that it's less damaging to the Earth, so that we don't have this incredible moral dilemma of raising and killing billions of animals that we basically torture from birth till death? Can we make those kinds of decisions? And can we implement those kinds of decisions?

CURWOOD: So much of what you've been talking about is industrialized agriculture. Our modern version of the enclosures that hit the serf or our modern version of the slave system that hit people, you know, back in the day and the ancient civilizations. So what will a decentralized agricultural system look like? And how do we get there? How do we do it? How do we get there?

BITTMAN: I don't know what it will look like. But it's not just about food. It's about strengthening democracy. It's about enabling more people to vote and talking to more people about voting, it's about building community, it's about organizing community. Food is an important issue. And in a way, I've come to feel like my job is to say, it's not just about climate change. It's not just about inequality. It's not just about the environment, racism, gender discrimination, all those things are super, super important. Let's elevate food to the realm of those other things. And let's put it in the mix and talk about it. Because it's something that everybody can agree on. Everybody can easily agree that we ought to have good food and that everybody ought to be able to eat it. So it has to be done regionally, the supply chain needs to be shorter, we need to have smaller farms, more regional food system, these are things that we're pretty sure we're going to be seeing, fewer pesticides, more agroecology or regenerative farming.

Mark Bittman is a columnist for the New York Times and the author of more than 30 books including the How to Cook Everything series. (Photo: Courtesy of Mark Bittman)

CURWOOD: And say more about agroecology. Not everybody listening to us or watching us is familiar with the way you describe it in the book.

BITTMAN: No, no one is. And one of the great things about agroecology, which is just a mash up of agriculture and ecology, is that it's such a terrible word that it has a chance of not being co-opted by big food. I mean, can you see cereal boxes that say 100% agroecologically grown? I mean, that might be a little tricky, whereas organic was an easy one. But agroecology acknowledges the need for short-term change, let's say organic principles, reduced pesticides, better soil health, better treatment of animals, fewer genetically-engineered products and so on down the line, but it acknowledges that those are just first-steps in getting land back into the hands of people, of building a just and equitable food system, and of building a just and equitable society, because ecology recognizes that we are one family. Ecology recognizes that we all live on the Earth, and that we have to protect the Earth, love the Earth, embrace the Earth, help the Earth survive. Those are important things. And it's not just a question of, do I eat organic food? Or do I eat less meat or whatever? It's a question of justice. It's a question of equality. It's a question of fairness, it's a question of sustainability. Those are sort of the big issues in agroecology, unlike organic, agroecology recognizes that this is a progression. We start by by doing what we can to build a better food system. It starts small, but it's about building community. It's about organizing, it's about strengthening democracy, better voting rights, and so on down the line.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you. The book, of course, is called Animal, Vegetable, Junk. The subtitle is, The History of Food from Sustainable to Suicidal. And the author, of course has been our guest today, Mark Bittman. Mark, thanks so much for taking the time with us today

BITTMAN: It was great, Steve. Thank you for your thoughtful interview. It was good to see you.

CURWOOD: Our conversation with Mark Bittman was part of our ongoing live event series, the Living on Earth Book Club. To find out how you can attend—online only for now-- please sign up for our newsletter on the Living on Earth website.That's L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth