Trump Rolls Back National Enviro Policy Act

Air Date: Week of July 24, 2020

Speakers from the Standing Rock Sioux Nation at a Minnesota rally against the Keystone XL Pipeline. In 2017, Federal Judge James Boasberg ruled that the construction the pipeline violated NEPA. In 2020, the pipeline was shut down. (Photo: Fibonacci Blue, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The Trump Administration has finalized a weaker interpretation of NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act. NEPA requires that the federal government study the potential consequences of major infrastructure projects like pipelines, dams, and highways, and consider less harmful alternatives. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain the significance of the rollbacks.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

A bedrock conservation law, the National Environmental Policy Act or NEPA, is the latest environmental regulation subject to rollbacks from the Trump administration. For 50 years the law has required that the federal government consider the potential consequences of new infrastructure projects like pipelines, dams, and highways. They must evaluate how those projects might impact human health, cultural resources, and endangered species to name a few and consider less harmful alternatives when possible. Now, claiming to slash costs, delays, and red tape for major infrastructure projects, the Trump Administration has finalized a weaker interpretation of NEPA. The new rules would narrow the types of impacts studied, set a higher bar for public comments, and exempt some projects from review entirely. Here to discuss the rollback is Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. Pat, great to have you back on Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby. Good to be here.

BASCOMB: I understand that it removes, basically, the requirement for analysis of cumulative or indirect impacts on the environment. So, for instance, you know, climate change. I mean, would NEPA ever apply to climate change, it's always going to be somewhat indirect, isn't it?

PARENTEAU: Yes, it isn't a direct, immediate effect. The cumulative loading of carbon in the atmosphere is what's causing global warming, causing sea level rise and all the rest. So this rule actually does something quite different than the proposal. The proposed rule simply said, cumulative impacts will not be considered. In this rule, the final rule, it says, it's up to the individual agencies to decide. So the rule is introducing a lot of uncertainty into the process. We now have a large number of judicial decisions, saying, of course climate change must be taken into account. And many of those decisions have overturned attempts by the Trump administration not to consider climate change in oil and gas leasing, coal leasing, gas pipelines and so forth. So the courts have uniformly said, of course you have to take climate change into account when you're writing your environmental impact statement. This rule now says, well, generally you do not, but we're leaving open the opportunity for individual agencies to do so in certain cases. All of which means we're going to have more litigation over that very question. So the rule isn't settling anything. It's raising more questions than it answers.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that makes it difficult, obviously, to have this hodgepodge of interpretations. Well, let's take a step back for a moment. What exactly is the National Environmental Policy Act, NEPA, what is it designed to protect?

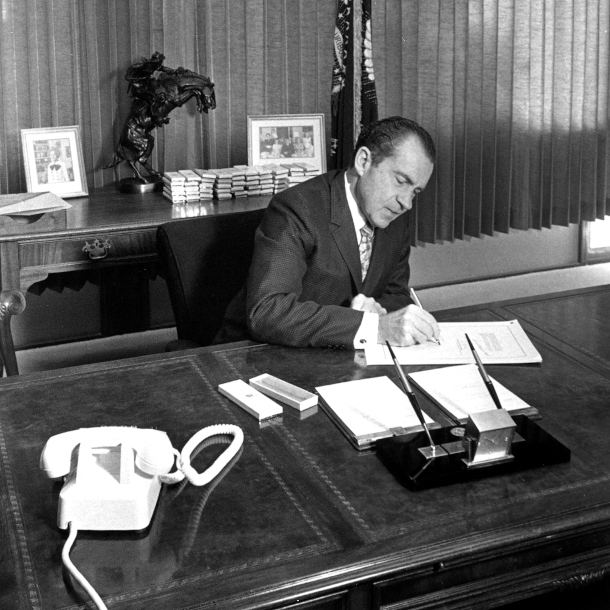

President Nixon signing The National Environmental Policy Act into law on January 1, 1970. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, Public Domain)

PARENTEAU: Everything! That's one of the great things about NEPA; passed in 1969. It's what we call "the Magna Carta of environmental law" because it's a basic statement of principle and policy. And it's sweeping in its scope. It's really designed, as it says, "For man and nature to live in productive harmony." So it has a lot of focus the long-term effects of the actions that we're taking now, effects on future generations was called out specifically in the law, historic sites, archaeological sites, Indian religious sites, aesthetics, you know, scenic beauty, the quality of life in inner cities and neighborhoods, green spaces. It's a "look before you leap" kind of approach to things. It's basically saying to agencies, when you think about building a highway, for example, why don't you think about other means of reducing traffic, because all highways do is generate more traffic, they don't really solve congestion. They sometimes make congestion worse. So NEPA was aimed at that kind of thinking, that there's only one way to control a flood, which is to build a dam. Well, no, not really. You could move people out of the floodway, and then you wouldn't have to build a dam. So it isn't just parks, and wilderness and wildlife. All of that's important too, but NEPA touches on virtually all aspects of the quality of life.

BASCOMB: And can you give us a couple recent examples of projects that have shown how NEPA can work and the potential behind it?

PARENTEAU: Yes, there are hundreds of case studies of how the NEPA process has enabled local communities to participate in decisions affecting their health and their community well-being. So NEPA is one of the primary tools that groups like those that are concerned about Keystone XL, the Dakota Access Pipeline, the recent abandonment of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and NEPA is a handle, a tool, that the community groups use to challenge those projects, challenge the very idea that we should be building all of this infrastructure which is propelling us more in the direction of climate change, but also the way these projects are sited in their communities, the way that they take account of pollution, spills from these pipelines. That's a big concern with Dakota Access. And then on a larger scale, NEPA played a role in getting some of these, what we call, "mission-oriented" agencies, like the Forest Service, to stop thinking that all that forests are is a basket of wood for wood products, timber, and so forth and look at them as ecosystems. So NEPA is a legal tool, it's a policy tool, and it's a community action tool.

BASCOMB: Now, the Trump administration looks at these rules and says they're going to slash costs, they're going to streamline the process, put people back to work doing these infrastructure projects and just, you know, get rid of red tape. How do you respond to that argument?

PARENTEAU: Well, we hear the red tape argument all the time. The truth is, some of the studies that have been done suggest the real reason for the delay is agencies trying to cut corners and not actually follow the law, or applicants for permits not actually doing the good work they need to do to evaluate the impacts and come up with alternatives. So you can't blame the law for mistakes that the people implementing the law are making. And you can't blame the law when people try to cheat and get around the law, find loopholes. I can point to a number of court decisions, where the judges have said, all you needed to do, to the agency, is simply follow the law. That's what the judge said about the Dakota Access Pipeline most recently, he told the Corps of Engineers, here's the problems with your analysis of a spill from your pipeline that might affect the water supply for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and you just simply didn't do it. So that's the problem a lot of times is, if you do the process right, you do your homework, the decision making should be a lot easier.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

BASCOMB: Now, of course, this is an election year and President Trump could have as little as five months left in office. To what degree do you see this as an eleventh-hour push to get some last minute things through and how effective might that be, given this timing?

PARENTEAU: It's clear that this is part of the President's push for energy dominance, for pushing through as many of these fossil fuel infrastructure projects as possible. It might benefit, actually, some other projects as well -- wind projects -- but the primary focus is fossil fuel projects. And it's clear that it's part of an election strategy. These proposals were made, of course, months ago, but this last minute push to get them approved and published and in effect, that's clearly tailored to the election cycle that we're looking at. So whether or not these rules will survive, of course, is a big question. I think the rule has a lot of legal vulnerabilities. And so it could be that the courts will step in as they have so many times to block what the Trump administration's rollbacks are seeking to do. And then of course, after the election, depending on how that goes, we could see other political responses to the rule as well.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. Well, ultimately, what kind of impacts do you think these weaker NEPA rules could have on environmental conservation if they do hold up?

PARENTEAU: Well, it'll certainly make it more difficult for local communities to have a seat at the table, and to have their voices heard, and to have projects modified to reduce some of their impacts. And a lot of these communities are minority communities. So there's a very strong environmental justice component to all of this. And in fact, the environmental justice community writ large, is probably one of the most active and concerned about these rules. I think if these rules were to survive, I think it's going to actually create more delay. All of these things are subject to judicial review and challenge, over and over again, sometimes. So there are many different ways in which a rule like this is going to create uncertainty litigation, and make it actually more difficult to get things done. There could be ways of improving the rule and the NEPA process. I'm sure there are. But this rule isn't the way to do it.

BASCOMB: Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for your time today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Bobby.

Links

NY Times | “Trump Weakens Major Conservation Law to Speed Construction Permits”

Washington Post | “President Trump Overhauls the National Environmental Policy”

NPR | “President Trump Overhauls Key Environmental Law to Speed Up Pipeline and Other Projects”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth