Dangerous Heat in the Gulf of Mexico

Air Date: Week of April 17, 2020

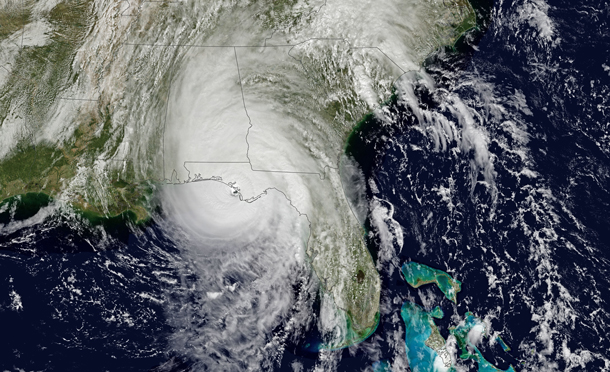

Hurricane Michael in 2018, developing off the Gulf Coast in the United States. (Photo: Joshua Stevens, NASA, Flickr, Public Domain)

On Easter Sunday, dozens of tornados tore through the southeast United States, resulting in the deaths of over 30 people. These deadly storms came as water in the Gulf of Mexico was three degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the long-term average. Atmospheric scientist Kevin Trenberth of NCAR explains to Host Steve Curwood why warmer Gulf water factors into many of the major storms that affect the United States, including tornados, thunderstorms, and hurricanes.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood, at a social distance.

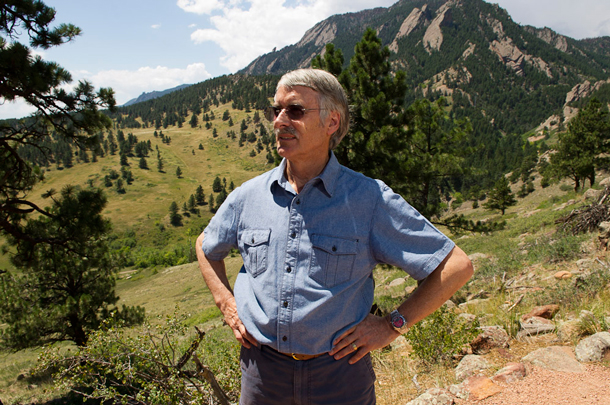

On Easter Sunday dozens of tornadoes tore across the South East of the US, killing more than 30 people. The deadly cluster of storms coincided with warmer than usual water in the Gulf of Mexico, some three degrees Fahrenheit hotter than the long-term average. Science links above-average sea surface temperatures in the Gulf to larger tornado clusters in the southern United States. And higher water temperatures are also a well-known factor in supercharged hurricanes. For more on what warmer Gulf waters might mean this year, I’m joined now by Kevin Trenberth. He is a Distinguished Scholar at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and a faculty affiliate with the University of Auckland in New Zealand, where he joined us on the line, just before the Easter Sunday tornadoes. Kevin Trenberth, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRENBERTH: Well, thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: The hurricane season in the western Atlantic Ocean typically doesn't begin until June. What kind of impact would warming waters this early in the year have on the upcoming hurricane season, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Well, as you said, it's a few months to go before we get there. Certainly, if it was three degrees above normal as we go into the hurricane season, that's sort of waiting around for any of the disturbances that occur in the right area to enable it to become perhaps more intense and with a lot of heavier rains than would normally be the case. And the, you know, the best example of that is Hurricane Harvey in 2017. But you know, we've got several months to go before then, and there's, you know, a lot of wind or other activity relating to thunderstorms and even tornadoes could well intervene before then and that helps to wipe out some of that warm water, perhaps.

CURWOOD: Now from what I understand, warm ocean waters can also have an impact on the tornado season inland. How does that work?

TRENBERTH: So, the tornado season has begun in the United States. It runs generally from March through June. So we're into it now. And warmer waters are providing a basic fuel if you like, a warm, moist air, and so that warm, moist air wants to rise and as it rises, the moisture condenses, it creates extra heating, we called latent heating in the atmosphere. This is where the heat comes back from the original heat that went into evaporating the moisture in the first place. And so different kinds of disturbances can tap into this, but they're all trying to move the heat away in some sense. So all of this convection in the atmosphere moves heat from lower levels into the upper part of the atmosphere. And then it gets transported by the jetstream and the circulation to other parts of the world. And some of it can actually radiate to space. So, and so this is one way the atmosphere actually responds. It depends quite a bit on the nature of the disturbances, whether they're a lot of, say individual thunderstorms, or whether there are these larger supercell complexes that can indeed trigger major tornadic outbreaks.

Severe damage to a grove of trees in Livingston, South Carolina following the Easter Sunday tornados. (Photo: National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office, Public Domain)

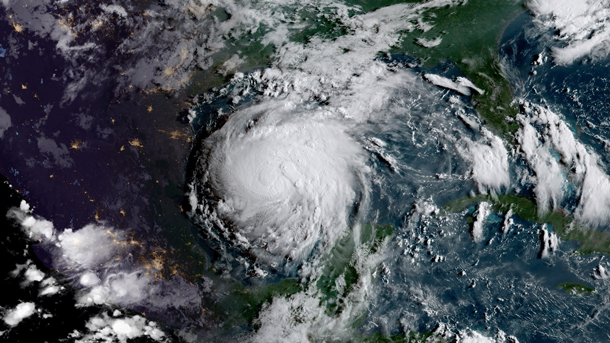

CURWOOD: Back in 2017, there were similarly warm waters in the Gulf and that had some pretty disastrous consequences. Hurricane Harvey with massive rainfall, as you pointed out, that's the same year that had Irma and Maria. So what are the odds of a similarly destructive hurricane season this year, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Yes, so it's going to depend upon the other parts of the Atlantic, because a lot of the disturbances that form hurricanes come off of Africa and they propagate across the Atlantic and then they develop if they find the right environmental conditions. And that certainly includes high sea surface temperatures, and so that was certainly the case in 2017. But the Gulf was exceptionally warm. And Harvey was a very unusual storm that tracked in from the southeast, and then stalled and became a Category Four so close to the land. The land normally helps to kill the intensity of these storms because it feeds drier air into the storms and also because of the friction that's in that area. But Harvey managed to pause in just the right spot, and all of the spiral armbands then just produced prodigious amounts of rain over the Houston area over 60 inches over about a three day period. And you know, the following year in 2018, one of the hotspots in the global ocean was off the east coast of the Carolinas. And so that was the case where Florence developed in that area. And that, you know, produced over 30, 30-to-40 inches of rain in the Carolinas and extensive flooding in that region. So where these hotspots occur can certainly attract activity of various kinds.

The hurricane season in 2017 was worsened by unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the most disastrous storms was Hurricane Harvey, which was a Category 4 and displaced over 30,000 people. (Photo: NOAA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how prepared do you think people are for this year's hurricane season? And how is that preparedness being affected by this novel coronavirus pandemic, do you think?

TRENBERTH: Well, you know, I've watched this with considerable interest and there have been numerous warnings in the past. And the lack of preparedness in the United States and other places around the world is really dismaying, I think, and this is a similar thing for hurricanes. You know, the big warning sign was in 2005 with Katrina and Wilma and Rita, you know, all these category five storms that occurred then and there was considerable concern. And I went to some meetings, which had heads of states of some of the islands in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, following that, and correctly, they were very concerned about two things, the rising sea level, and hurricanes, stronger hurricanes. So the concern was certainly there. What has been disappointing from my standpoint is how little preparedness seems to have developed and this was brought home in 2017 with Harvey, the total lack of adequate drainage systems and building in wrong places and building structures that weren't prepared in Southern Texas. Also, Irma went right up Florida. And then Puerto Rico, the lack of preparedness in Puerto Rico is astounding, appalling. And in fact, even places like Cuba, were somewhat better prepared than Puerto Rico was. And so, you know, the warnings have been there, why isn't there more effort to prepare for the sort of thing scientists have more or less guaranteed, but you can't say, you know, exactly when. And so this is the paradigm for global warming. You know, global warming is coming. One of the differences with global warming is that with the COVID-19 virus, we think we can develop cures, we can develop a vaccine. But once global warming is here with us, there's no vaccine that is going to be developed that will make that go away. So I think this is a warning sign, and I certainly hope the governments around the world and the peoples around the world can take account of that.

Kevin Trenberth is a Distinguished Scholar at the United States National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a faculty affiliate with the University of Auckland in New Zealand. (Photo: Courtesy of Kevin Trenberth)

CURWOOD: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished scholar at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research and an affiliate member of the faculty at the University of Auckland. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kevin.

TRENBERTH: Oh, you're most welcome.

Links

Science Alert | “By the Way, Antarctica Just Experienced an Unprecedented Summer Heatwave”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth