Fracking and Your Health

Air Date: Week of July 19, 2019

Fracking pads and roads, seen here from the air, can turn a rural landscape into a network of industrial infrastructure. (Photo: Simon Fraser University, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Fracking forces water, sand and chemicals into shale rock at high pressures, extracting much more oil and gas than conventional wells. But this highly efficient method comes with environmental and health risks including birth defects, cancer, and asthma. A new meta study brings together the findings of more than 1700 studies, articles and reports on the health impacts of fracking. Coauthor Sandra Steingraber, a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the importance of this massive body of evidence.

Transcript

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

Fracking has revolutionized the extraction of oil and gas in just a few years. By forcing water, sand and chemicals into shale rock at high pressures, companies can extract more oil and gas than using conventional wells. But this highly efficient method comes with environmental and health risks, and a growing body of research ties the fracking activities to a host of health problems including birth defects, cancer, and asthma. A new meta study jointly published by Physicians for Social Responsibility and Concerned Health Professionals of New York brings together the findings of more than 1700 studies, articles and reports on the health impacts of fracking. It’s the sixth edition of a report originally released in 2014, which helped inform New York State’s decision to ban fracking. A group of public health professionals that included Sandra Steingraber, a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College, wanted to make sure science was part of that decision.

STEINGRABER: So we went to work, translating the science into plain English for our political leaders, members of the press, and most importantly, people in frontline communities who are going to be compelled to endure the risks that fracking brings to people's health. And when we first did this, we didn't call it a compendium, we called it a memo, [LAUGHS] because there were only nine studies in the peer-reviewed literature. And then when we finally banned fracking in New York in December 2014, we had an edition of the compendium with 400 studies. Well, at that point, people all over the world were at this same point in thinking about fracking, whether to allow it or not allow it. And so our Compendium was in great demand. So we've kept going with it.

BASCOMB: So what was your basic finding in this most recent report?

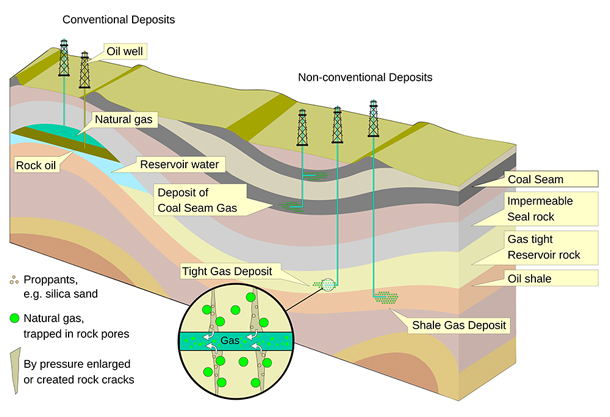

A diagram of “non-conventional” deposits accessed via fracking, which releases tightly-held oil and gas within shale rock. (Photo: MagentaGreen, Wikimedia Common CC BY-SA 4.0)

STEINGRABER: Well, we looked across a wide range of parameters. We looked at air pollution, water pollution, radioactivity, social disruption, we looked at impacts on climate. And across all these data, we saw a plethora of recurring problems and harms. And we uncovered no regulatory framework that could avert these harms. So in other words, there's no evidence that fracking can operate without threatening public health directly or without imperiling climate stability, on which public health of course depends.

BASCOMB: And so what are the public health concerns associated with fracking?

STEINGRABER: Well, there are 17 different topics in this Compendium and it starts off with air pollution. Air pollution accompanies fracking wherever it goes; things like methane leaks that result in smog, ground level ozone, which is a killer. So we know ground level ozone contributes to stroke risk, to premature birth, to heart attack, and to asthma. And then when we actually looked at public health effects measured directly, we saw in places where there is a lot of fracking activity, the kinds of health effects that are linked to this kind of air pollution. And I think what we would agree is the most troubling, is pregnant women who live near drilling and fracking operations during pregnancies are at higher risk for poor birth outcomes, including premature birth, including certain kinds of birth defects, including small for date births, meaning, infants are born quite small for the number of months of pregnancy.

BASCOMB: And is the only way that people are exposed to it is by air, or is it also in the water?

Studies show pregnant mothers living near fracking operations are at a higher risk of delivering their babies early. (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

STEINGRABER: Water contamination by fracking is a proven thing. Fracking relies on using our fresh drinking water sources as a club to shatter the shale below our feet. The idea here being that there are bubbles of methane -- natural gas -- and oil that are actually trapped inside the rock, they won't flow up the borehole on their own. So we use our freshwater resources to shatter the shale and get at those bubbles of methane. But when the water comes back up again, it's contaminated not only with toxic fracking chemicals that were added in the first place, but also there's a whole periodic chart of toxic chemicals down in the shale, things like heavy metals, arsenic, barium, strontium, uranium. And some of these things, like radium and radon, are actually radioactive. And the question is, how do you dispose of all that? And the actual standard practice is to re-inject it into the ground again. But this raises the risk for contaminating our drinking water aquifers, which this wastewater has to be pushed through. And in addition, because there are lots of lubricating chemicals that are added to fracking fluid, you can actually lubricate fault lines and trigger earthquakes. And we have a whole section dedicated to public health and safety risks around seismic activity.

BASCOMB: Now I understand that there's also an environmental justice component to fracking and health impacts. Can you tell me about that please?

STEINGRABER: Fracking has an environmental justice component for sure. The oil and gas, of course, are located under many parts of the United States. But where fracking infrastructure and fracking well pads are located, turn out to be disproportionately sited in communities of color, poor communities, and rural communities. No one wants to live next to a massive, loud industrial zone that 24/7 exposes you and your family to toxic chemicals, to noise pollution, with massive truck traffic going back and forth, risk of earthquakes and so forth. And so toxic facilities tend to be sited in communities that can offer the least resistance, in communities where people don't necessarily have friends in Congress, they don't have legal assistance, it's difficult mount a strong resistance. In one case in Colorado that we looked closely at, fracking well pads were initially planned to go in next to a school servicing largely white children from wealth, in a wealthier community. And that community succeeded in pushing it back. And then it landed next to a school where a lot of poor kids, who were not white, and whose parents didn't speak English, and perhaps had undocumented immigrants living there, who were less likely to speak out.

BASCOMB: And this report also looked at how fracking contributes to climate change. Can you tell me what you found along those lines?

STEINGRABER: Climate change is the big theme of the sixth edition of the Compendium. And that's because the data are really clear now that methane is surging in the atmosphere. It started rising really rapidly around 2007. And methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, about 86 times more powerful over a 20 year timeframe than carbon dioxide. And 20 years, of course, is about the length of time we have left to really get the climate stabilized and decarbonize. So we have to look closely at methane. So increasing evidence suggests that North American fracking operations are driving a lot of that surge. And we're discovering that fracking operations and all their attendant infrastructure, all the way to the pipelines, to the compressor stations, to the distribution pipes that bring it into your home, are far more leaky than we formerly appreciated. And there are no good fixes for this problem. So all of this is quite alarming, showing us that fracking is absolutely incompatible with climate stability.

Methane, which is most of what makes up natural gas, is a very potent greenhouse gas, and studies have shown that it can leak via infrastructure from the point of extraction, through pipelines, all the way to the point of use. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: But we've been told that fracking and natural gas is a bridge fuel, that it's going to help us get out of the problem with climate change.

STEINGRABER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, the metaphorical, mythical bridge. That's been an industry talking point since the very beginning. And there was never really a lot of data to suggest that natural gas worked that way, but at this late stage in the climate crisis we find ourselves in, we know that that's absolutely not the case. To put a more hopeful spin on it, and why the bridge metaphor doesn't really make sense, is that we're already on the other side of the water, right? We have renewable resources that are deployable now, in the form of solar, wind and water power that can be backed up with battery storage, obviating the need for fracking. So fracking is no longer a bridge. It might have been a bridge 80 or 90 years ago. Today, it's a wrecking ball that is swinging at our climate.

BASCOMB: So what kind of reception have you had to your report, now that it's out?

STEINGRABER: We get emails every week from people who are submitting it as expert commentary, bringing it to their elected representatives, holding reading groups in their synagogues and churches. It's always gratifying to see, especially in this day and age where this administration has turned its back on science in general and on climate science in specific, to see people hungry for this information. And from the ground up this science is really making a difference.

BASCOMB: Sandra Steingraber is a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College and coauthor of the sixth Fracking Science Compendium. Sandra, thank you so much for taking this time.

STEINGRABER: Thanks for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth