Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

Air Date: Week of June 14, 2019

Coronado National Forest has an area of nearly 2 million acres spread throughout southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, including the Sky Islands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson, Arizona is the latest subject of Living on Earth’s occasional series on America’s public lands. There’s plenty of heat and cacti, of course, but also many species ordinarily found far north of the desert Southwest. With a local biologist as her guide, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on the remarkably diverse biomes of Arizona’s Sky Islands.

Transcript

CURWOOD: More than 50 percent of Arizona is actually public land, a tapestry of state and federal land, including national parks and forests. That makes it an excellent destination for summer travels. I know what you may be thinking…. Arizona in summer time? No, thanks! Well, for this installment in our occasional series on public lands, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb visited the Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson and found the forest there is literally full of cool surprises. She went on a hike and drove up Mount Lemmon, roughly 80 miles north of the US border with Mexico. It’s a popular destination for locals and tourists alike.

[SFX CAR PASSES]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on the side of the road at the base of Mount Lemmon. It’s sunny and a pleasant 75 degrees. Sharp grasses and spiny succulents with bright yellow and pink flowers blanket the parched desert ground. I’m here with wildlife biologist Sergio Avila.

AVILA: We can see Sonoran desert plants and animals. We can hear right now some Cardinals, we can hear some Curve-billed thrashers, we can hear some mockingbirds.

BASCOMB: Sergio is outdoors coordinator for Sierra Club in the Southwest Region. Originally from Mexico, Sergio has thick black hair pulled back in a low ponytail.

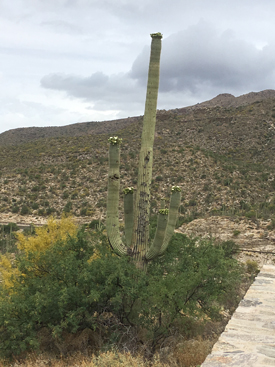

AVILA: We are looking at the saguaros, which is the iconic, kind of descriptive plant of the Sonoran Desert.

BASCOMB: These saguaro cactuses stand sentry some 60 feet tall with large white flowers on each of their massive arms reaching upwards. I think the inventors of those cactus-shaped margarita glasses must have had the saguaro in mind.

The Saguaro cactus is an icon of the Sonoran Desert. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: So, for a plant like this, to have some arms, at least 250 to 300 years have passed for them to have their arms. So a lot of these saguaros that we see here are easily three, 400 years old, so they're ancient saguaros.

BASCOMB: Some of these cactuses may have been here when the Spaniards were establishing settlements. But Sergio says the native people of the area, the Tohono O’odham, have always had a close cultural connection with the saguaro.

AVILA: The new year, or the year for the Tohono O’odham starts on July 1st, and that is connected to when the fruit of the saguaro drops from the plant and around when the rainy season starts.

BASCOMB: And he tells me the fruits of the saguaro are an important food for everything from mice and skunks to foxes and coyotes. Their flowers provide pollen for a variety of bats and birds. The shallow roots are crucial for holding soil intact during the monsoon rains. And the body of the cactus itself provides housing for a number of residents.

AVILA: Saguaros are like apartment buildings with cavities, and so little owls, kestrels, woodpeckers, many other birds depend on saguaros to live inside of these cavities.

Sergio Avila is a wildlife biologist, as well as an outdoor activities coordinator with Sierra Club. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Unlike the Sahara, the monsoon rains pour on the desert here each summer, and scientists say that makes it this the wettest desert in the world. So even in the dry season, the Sonoran landscape is teeming with life. But as captivating as it is, there is so much more to see. So, Sergio and I pile into our car and head up the mountain.

[SFX CAR DOOR SLAMS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We drive around a bend in the road and suddenly the saguaro are gone. Within 1000 or so feet of elevation gain, it’s too cold for them.

[DRIVING SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

We pass a scenic overlook, Tucson lies below us, and from here it’s clear to see why these are called sky islands.

AVILA: The sky islands, here in Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent parts in Mexico, are mountain ranges surrounded by grassland sort of deserts that make them look like islands.

BASCOMB: Back 15 to 20 thousand years ago, the climate of the southwest was much cooler and wetter. With the end of the last ice age, temperatures rose and desert came to dominate the landscape. But at higher elevations, temperate plants and animals were able to survive. Today those remnant biomes are marooned as mountain islands, surrounded by the sea of the desert.

Mount Lemmon. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: In this region of the sky islands, is the only place, or is the place where jaguars and black bears meet. It’s the place where you have northern birds like sandhill cranes, and birds from the tropics, like military macaws.

BASCOMB: The Sky Islands sit at the confluence of 4 different ecosystems, the Rocky Mountains to the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, and Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts. With so much diversity in one area, Sergio says, the sky islands are a biodiversity hotspot.

AVILA: So this biological region brings together a species from the north and the south that they don't meet in anywhere else.

[SFX CAR DOOR SHUTS]

BASCOMB: We get out of the car and walk along a small trail. The path we are on is actually part of the Arizona trail that goes from Mexico to Utah. We are driving up Mount Lemmon today but you can also hike the mountain in about 5 hours.

AVILA: I think right here we're at about 4500 feet of elevation. We've been going up on the mountain, and you can see a little bit of the change. Now we start seeing some oak trees. And I have to say, I'm pretty cold.

BASCOMB: I'm chilly.

AVILA: Yeah, yeah, let's go see what we see over here in the trees.

BASCOMB: We’re walking in an oak woodland, but dotted in the understory of a forest you might see in Pennsylvania are huge cactuses, waist high covered in orange and yellow flowers.

AVILA: This is a prickly pear. Eventually those flowers will turn into prickly pear fruit, which is a super juicy fruit that is a tremendous food source and water source for a lot of animals.

BASCOMB: It makes a good cocktail too.

AVILA: Oh, well I'm glad you mentioned that because part of the trip includes prickly pear fruit margaritas and that is a sky island staple. (laughs)

The Sky Islands are in the midst of four different ecosystems – the Rocky Mountains in the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, the Sonoran Desert to the West, and the Chihuahuan Desert to the East. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh perfect.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

AVILA: One thing I wanted to share, for example, this region has four different species of skunks.

BASCOMB: Really?

AVILA: Yeah, so it’s not, you know, just skunks, but we have striped skunks. We have spotted skunks, we have hog nose skunks, and hooded skunks.

BASCOMB: And are they all just as stinky?

AVILA: No! Those who are specialists in skunks actually say that different skunks smell different. Those who have experience with skunks can even tell one skunk species from the other from their smell. Which, you know, I think it's a level of skill that I don't know if I'm ever going to get to but…

BASCOMB: Do you really want to practice? [LAUGHS]

AVILA: Ah, exactly right. Like, what does what does it take to learn that? But it also speaks about … skunks, eat insects, skunks dig around for rodents, skunks might eat some reptiles. So the fact that we have four different species of skunks, in my mind says that we have a tremendous diversity of insects and rodents, and everything that is food for skunks, you know what I mean? We also have two different species of deer, white tail and mule deer, or black-tailed deer, that are adapted to a different elevation. We have four different species of cats in this region. The better-known bobcat, which is the short one with a short tail, and the mountain lion, or the cougar. And then the tree tropical ones, which are the ocelot, and the jaguar, the two spotted cats that come from the tropics. Having four species of cats, it's also an indication that we have a lot of different animals that can be food. And so the sky island region is a really good example of a whole ecosystem working together.

BASCOMB: So, these sky islands are a chain of mountains that start near San Javier, Mexico, 300 miles south of the border, and run into Aravaipa, Arizona, some 200 miles north of the international boundary. These mountains are a crucial corridor for migrating animals, like jaguar, that can migrate several hundred miles in search of territory and a mate. So, I ask Sergio how a high-security border wall could affect migrating wildlife.

Sky islands are mountains whose ecosystems are drastically different compared to their surrounding lowland environment. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: You might be separating populations of carnivores, you might be separating populations of herbivores that are making use of some areas. And so this rich diversity in our region is very important. And it's one of the things that is under threat, short term by the border wall and other infrastructure there, and long term by climate change.

[CAR SOUNDS, DRIVING]

BASCOMB: Back in the car, we head up the mountain again. At about 7,000 feet of elevation, the oaks and cactus give way to pine trees. It looks exactly like a typical forest in New England. Around the corner we need to stop the car.

SERGIO: So we're looking at two white-tailed deer on the side of the road. They look like really young fawns. I would say these are young, from this last summer. I wonder where mom is.

BASCOMB: We peer into the thick vegetation, but don’t see mom, so once the deer are safely across we continue on to the top of the mountain to the Mount Lemmon Ski Valley. That’s right, alpine skiing in Arizona.

SERGIO: We are at 9000 feet of elevation in the ski area, the top of Mount Lemmon. We are surrounded by a meadow of aspen. If you've ever been in Colorado, you will recognize these trees very quickly. And we are in front of this ski lift and it is snowing. And here we are prepared for a field trip in the summer in Arizona and we are super cold.

Mount Lemmon reaches heights of over 9,000 feet and its summit area receives around 200 inches of snow every year. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: I'm wearing shorts and a sweatshirt and I'm uncomfortable. The thermometer in the car says it's 35 degrees up here. There’s snow sticking in your hair.

AVILA: Yeah. I also wanted to say we are seeing different birds, we saw a robin. Seeing different colored birds, but it is very gray and clouds are very dense. And so even the sound is kind of like hard… It’s not very noisy right here and so we only hear the wind blowing in the aspen trees. It is pretty, but it is cold.

BASCOMB: When we were driving up here we saw signs that say snow plow ahead and beware of ice, and that sort of thing.

SERGIO: And we were laughing at those signs on the road. Yeah, what did we know?

BASCOMB: We're not laughing anymore!

SERGIO: We’re not laughing anymore, no!

The trail map for Coronado National Forest, outlining the Sky Island Scenic Byway. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In terms of the climate and habitats, we’ve gone from Mexico to Canada in less than an hour. We warm up with some hot chocolate at the top of the mountain and then head back down the way we came. My ears pop with the sudden elevation change and I’m struck by the remarkable diversity one small mountain has to offer. And in the monsoon season, it’s different still, when a flush of life emerges to greet the rain and complete an entire life cycle in a matter of weeks. Far from the barren desert one might imagine, the Sky Islands of Arizona are full of surprises and well worth a visit nearly any time of year.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in the Sky Islands of Arizona.

Links

Listen to Living on Earth’s most recent segment on the National Parks

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth