In Search of the Canary Tree

Air Date: Week of March 8, 2019

Southeast Alaska’s Nootka cypress also known as the yellow cedar tree, is in trouble. Climate disruption is bringing more erratic weather to the area, and the huge cypresses known as yellow cedar trees are among the first species to suffer. In the book, “In Search of the Canary Tree: The Story of a Scientist, a Cypress, and a Changing World,” author Lauren Oakes describes how Southeast Alaska’s forests and people are responding to the widespread die-offs of the yellow cedar trees. Lauren Oakes joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how resiliency is helping the forest and local human communities adapt to the loss of this culturally and ecologically important species.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Alaska, the “Last Frontier” state, is one of the first frontiers when it comes to the impacts of climate disruption. Over the past sixty years the state has warmed an average of three degrees Fahrenheit, but an average of six degrees in winter, according to the EPA. That has devastated a key species found in temperate rainforests: the Nootka cypress. Many people also call it the yellow cedar. In her new book In Search of the Canary Tree, author Lauren Oakes traces her quest to understand how forests, and the people who depend on them, are adapting to the widespread loss of this tree.

OAKES: I came to Alaska looking for hope in a graveyard. Ice melting, seas rising, longer droughts, in a world seemingly on fire, I chose to put myself in some of the worst of it. The Alexander Archipelago in Southeast Alaska is a collection of thousands of islands in one of the scarce pockets remaining on this planet, where thick moss blankets the forest floor and trees range from tiny seedlings to ancient giants.

But I wasn’t loading into a Cessna 4-seater to look for fairytale forests of spruce, hemlock, and cedar. I was flying in search of the forests I’d study. The graveyards of standing dead trees and the plants I so wanted to believe could tell me, through science, that maybe the world is not coming to an end.

“In Search of the Canary Tree” is Lauren Oakes’ first book. (Image: The Hachette Book Group, Inc.)

CURWOOD: Author Lauren Oakes joins us now from Bozeman, Montana. Welcome to Living on Earth!

OAKES: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be on the show.

CURWOOD: So in your book, you describe what you call an eerie sight of the standing dead, the yellow cedar trees that have died in massive numbers in recent decades. Why is this going on?

OAKES: So it's an interesting story, a little bit counterintuitive when it comes to climate change, because they're essentially dying as an impact from freezing events. And that seems a little bit weird in a warming world. But in the Pacific Northwest, what we're seeing in terms of climate change is an increase in precipitation as rainfall and a decrease in snow. And snow basically acts as an insulator, a blanket on their roots. These trees have really shallow root structures, and they tend to be found in these kind of boggy, more wet soils. And so in the springtime when you get earlier warming, the trees basically de-harden and they're thinking, Okay, it's ready for summer. It's like taking off your winter coat. But it turns out that there's still some cold events that come in and persist in spite of climate change and those come from the interior or off the coast. And it's that combination of events where you have the roots vulnerable without their warm blanket on them, and then a sudden cold snap, that damages them and their ability to update nutrients.

CURWOOD: How would you describe a yellow cedar tree and the southeast Alaskan coast where you studied them?

Yellow cedar foliage. (Image: Kate Cahill)

OAKES: Well, Southeast Alaska is just -- I do hold it near and dear to my heart. It's a beautiful landscape in a place that feels more remote than really anywhere else in the world I've been. Many of the communities are accessible only by boat or plane, so there's also a real sense of community in the towns because people are living, you know, more connected to one another and perhaps, you know, more disconnected from the rest of the state or even from the country. But in terms of weather, sure, it's a coastal temperate rainforest It gets a lot of rainfall, it's damp, it can be cold, summers are starting to see more sunshine and there certainly have been some sunny summers in recent years. But you also do get a fair bit of rain. And the trees themselves are quite distinct. Dr. Paul Hennon was one of the people that I worked with, and he ends up being a character in the book; he used to tell me early on, Well, when you fly in a plane for the first time, you're going to be able to tell which one's a yellow cedar tree, and which one's not. And I thought that was kind of crazy, could you really distinguish a tree from the top, flying in a plane? But the truth is, yes, they have a different color. They have these sweeping limbs that hang down, so from above, as a bird's eye view, they look quite different. And standing underneath them, they're just beautiful.

CURWOOD: What drew you to study how forests are responding to the yellow cedar die-off?

OAKES: I was attracted to work in the north because, well at the time there was a lot of attention on the poles because the poles are warming at faster rates than the global averages. And I thought going in that I wanted to do a project up north, climate change-related because I felt there was a need. And I also thought that potentially there could be lessons there for elsewhere. But I really didn't know what I would study. And I spent a summer of doing exploratory research, trying to talk with people about the kinds of climate impacts they were facing. And in that process, I met Dr. Paul Hennon, who is a forest pathologist with the United States Forest Service. And he was just about to publish, basically a synthesis of 30 years of research showing that climate change was linked to the death of these trees. And for me, that seemed like a perfect starting point for the question of what happens next, what happens in the forest community? How does it develop in response to the death of these trees? And then also, how are people coping with those changes -- are they coping with those changes and in what ways?

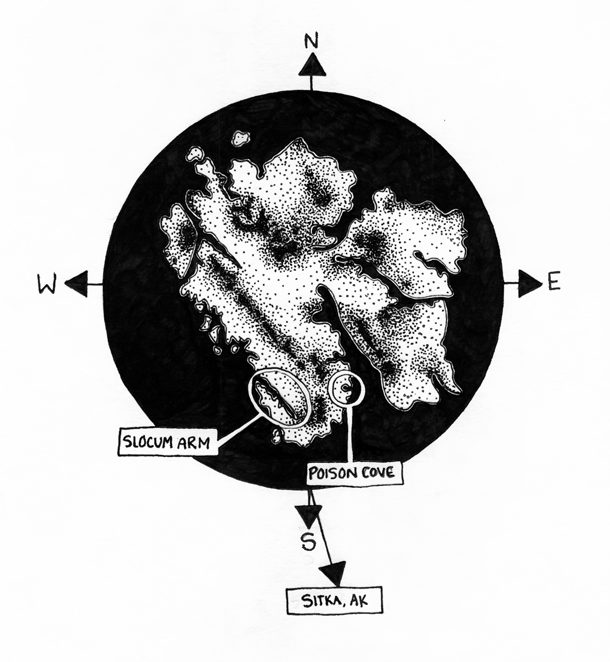

A landing beach in Klag Bay, north of Slocum Arm on Chichagof Island where a yellow cedar dieback occurs. (Photo: Lauren Oakes)

CURWOOD: A lot of people don't want to look at the mouth of a monster, and certainly climate disruption is a monster that could devour our civilization. Why you? Why Lauren Oakes saying, hey, let's see what happens here?

OAKES: There was an attraction to me of learning in place, of spending time in a community to understand both effects on the environment and people, on the relationships between them. And why look towards the future? I feel like that's where we need to be looking, and there's often a tendency to think more short term, but we've been lagging for a while now. And now a lot of those impacts that seem far off are here and we need to figure out how to cope with them.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about your research. What did you find was happening in the forest in response to the yellow cedar die-off?

Lauren Oakes conducted much of her research on Chichagof Island, off the coast of Southeast Alaska. (Image: Kate Cahill)

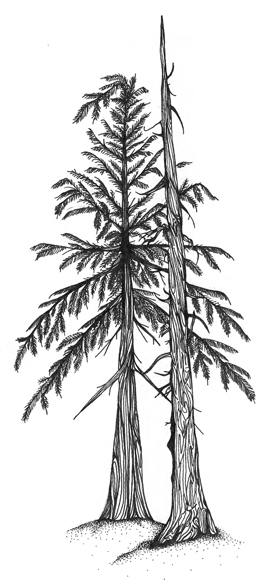

OAKES: Well, there were a couple things that were surprising. The first is that not all the yellow cedar trees in the forest affected are dying, there are still some survivors. So in some of my sites, on average, about 80% of the trees were affected, but that leaves 20 that were still doing okay. And then of course, there are still some pockets where you'll find healthy populations -- up in Glacier Bay National Park, a strong population of healthy, thriving individuals. So that speaks to me of, you know, the effects of microclimate, how it's variable. And ecologically that was interesting to me. But now, philosophically, in writing the book, I thought about it in terms of, Okay, well, what does that mean for people? Will there be places where we're impacted more than others, and places where we need to care for one another, reach out for one another; and places where we still may be able to thrive. So that was one finding. But another was that despite the loss of these trees, there is a flourishing forest. That it takes time for it to recover and to grow into something new, but ecologically what I saw was another conifer species, Western hemlock, taking over so ultimately these trees would grow into the gaps created by the yellow cedar trees. In the field we call them hugs, because you could literally see this Western hemlock tree that had started as a little tiny sapling right next to a dead yellow cedar and grown up so close to it that its branches just reached around the trunk of the dead one, reaching towards the light. There were also changes in the understory plant community. So initially following the death of the trees, you tend to lose mosses and bryophytes, those real, you know, sponge-like members of the plant community, when you think of these kind of dreamy rain forests. They may be responding to the increase in light that then reaches the forest floor. And you see an increase in shrubs -- things like vaccinium, and menziesia, and also some forage that deer rely upon.

CURWOOD: So what did you find out in terms of why it mattered if the yellow cedar turned over to hemlock -- who was affected by that and how did they respond?

A Western hemlock growing up beside a dead yellow cedar, in what scientists casually refer to as a “hug”. (Image: Kate Cahill)

OAKES: Yeah, so partly how people were affected depends on their relationship to the trees. So there's two kinds of attachment, they call it nature attachment, actually, emotional or functional, right? So the emotional is that we have a connection to place, to maybe a trail you hike, or something in your own backyard. And the functional is, you know, more like ecosystem services, what a resource, if you will, provides us: the water we draw from it, or the wood we use from a tree. And so people's relationships to these trees, in part, had influence on how they responded. And the ones who had these emotional ties had a process of grief associated with it. And they were not only losing some of their cultural heritage, for example, or, you know, recreation interests, but also a real relationship that some might only attribute to something we have with other people. And I went into it studying what's called the KAB or the knowledge-attitudes-behavior framework, and it's something researchers use to look at what might cause behavioral change. So for example, it's used in human health to say like, what might motivate someone to change their diet or in the environmental world; what about recycling? What can motivate somebody to recycle? And the theory is that if we're knowledgeable about something, we'll have certain attitudes or be concerned about it. And then that will motivate behavior. Sometimes it holds true and sometimes it doesn't. So I went in thinking, how knowledgeable are people about these impacts? Do they know that it's caused by climate change? If they do, does that affect their attitudes about it? And what do we see in terms of behavioral change or adaptation?

CURWOOD: And the answer was?

OAKES: Well, I definitely found that people who were knowledgeable of the impacts and knew that they were caused by climate change responded differently. They were, yes, making changes in their own community. So for example, innovating their business to make use of other species or make use of the dead trees or changing their use of the forests through recreation, or hunting, etc. But they were also more concerned at a global level. They acknowledged that this, you know, seemingly distant, massive, unwieldy, somewhat unwieldy thing we call climate change was really hitting home and that often led them to be more likely to engage in global actions -- which could be educating others about climate change by using the trees as an example; feeling more motivated to reduce their home energy use; do things like biking to work. So that's in some ways where the canary in the coal mine comes from. This tree became the canary in the coal mine for the people I interviewed, but then also for me, and my writing process. And you know, I hope also for the readers in the future.

CURWOOD: And for those who didn't really understand that this is related to climate disruption. What did they tell you?

OAKES: Yeah, so you might see, if they knew of the changes occurring, so they could see the dead trees, they had access to them, and they used the trees in various ways, they still might innovate and make use of the changing environment. But that aspect of the link to global action was missing. And they also didn't face a whole suite of psychological responses. So the people who were knowledgeable that climate change was impacting these trees had another level to deal with, which was coping with the knowledge that this is climate change. And that seems negative. But I also see it as a positive because it's part of a grief process. It's part of acceptance and in any grief process, we're accepting loss but also looking towards what new life is created. How do we adapt to these changing conditions and how to the relationships in them vary?

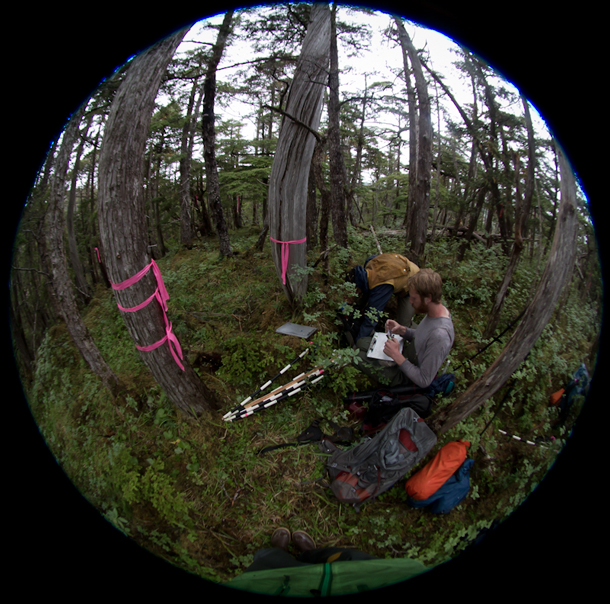

Lauren Oakes’ research colleague Odin Miller checks the data he recorded from surveying understory plants. (Photo: Lauren Oakes)

CURWOOD: What advice do you have for our listeners who might feel, let's face it, pretty exhausted from the constant onslaught of bad environmental news, especially the notion that our climate is really starting to spiral out of control towards a very uncomfortable place.

OAKES: Yeah. So what motivated me to write the book was that when I finally finished the research I was doing, I still felt like I was struggling with this question of how do you live with what you know, as a scientist now, and a citizen? And do you have hope about the future? I am like many others in that I feel like the headlines are tiring and exhausting, and have a lot of doom and gloom in them and make us think that the whole future on climate change is quite dark. And yes, there are dark impacts coming but I also realized in both my research process and in my personal process of trying to sort out how do I live with this knowledge is that I want to put myself in the camp of someone doing something, someone feeling like we still can make a difference and cope, and think about what that means in terms of my own actions. So a lot of us are kind of waiting for top down decisions to come, whether that's our president finally acknowledging climate change, or as a world meeting the Paris Agreement, but I think there's a lot that we can do at the local scale, both in terms of mitigation and in terms of adaptation.

Lauren Oakes is a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and an adjunct professor in Earth System Science at Stanford University. (Photo: Clayton Boyd)

CURWOOD: So how fair is it to say that one secret for happiness going forward might be resiliency?

OAKES: For sure. Yeah. So one of the things I write about in the book was that I had this series of questions where I was asking people about their future outlook. And I asked them a series of three questions. And I wanted to know, what was the environmental problem they were most concerned about? And did they think that there was a lot or nothing that we could do about it? How optimistic were they about the future. And I say in the book that I never had scientific results from that. So there were a lot of people who identified climate change. And of them, some of them were really optimistic and some were completely negative. So the scientist in me said, Okay, I could go back and interview more people or there should be a bigger study here. But instead I took it as a personal lesson that we have a choice, every day in how we wake up and face this world and the problems that we have. And I want to put myself in the camp of people who feel optimistic, who are looking for opportunities who can make a difference, even if it's at a tiny tiny scale.

CURWOOD: Lauren Oakes is a conservation scientist at the Wildlife Conservation Society. Her new book is called In Search of The Canary Tree. Lauren, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

OAKES: Thanks for having me.

Links

“In Search of the Canary Tree: The Story of a Scientist, a Cypress, and a Changing World”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth