New England's Stone Walls

Air Date: Week of November 30, 2018

Many of New England’s stone walls, like this one in New Hampshire, are going back to nature as they fall into disrepair and become overgrown with moss. (Photo: mwms1916, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

New England’s first farmers of European descent found themselves plowing soil strewn with rocks left behind by glaciers. So, stone by stone, they stacked the rocks into waist-high walls. Some say these walls helped win the American Revolution, and they later inspired Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall.” Host Steve Curwood goes for a walk in the woods of New Hampshire with stone wall expert Robert Thorson, the author of Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls.

Transcript

BASCOMB: The colonists in New England faced an uphill battle in turning the region’s vast forests into farmland. They had to fell massive trees and contend with rocks strewn throughout the soil they aimed to plow. So, stone by stone, they stacked the rocks left over from glaciers into waist-high walls. Each year frost heaves pushed still more stones to the surface, which some of those early farmers said was the work of the devil.

Generations later, farmers returned time and again to repair the walls as the years went by. That’s the subject of Robert Frost’s famous poem, The Mending Wall, read here by the poet himself.

FROST: Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbour know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

"Stay where you are until our backs are turned!"

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, "Good fences make good neighbours."

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

"Why do they make good neighbours? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down." I could say "Elves" to him,

But it's not elves exactly, and I'd rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father's saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, "Good fences make good neighbours."

A New Hampshire stone wall in winter. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Those stone walls of Robert Frost’s verse still exist in Southern New Hampshire, as do thousands like it across New England. Made mostly of granite, these walls serve as windows into the geological and cultural history of the region. I went for a walk through an old farmstead with a stone wall expert to learn more.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: So, we're here in Nottingham, New Hampshire, at a 1755 farmhouse. It's surrounded by stone walls, and we're joined now by Robert Thorson. He's a professor of geology at the University of Connecticut. And he's author of “Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England's Stone Walls”. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor.

THORSON: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, how did you first get involved studying stones?

THORSON: Well, I moved here from Alaska, and I had grown up in the sort of Scandinavian Midwestern upper Midwest heritage where you don't see any stone walls whatsoever and I moved here from Alaska in 1984. And I thought, well, I'm hired as a landscape archaeologist and a geologist and a scientist to teach. And I thought, I better go get myself a look at stone walls. And so I went to the Natchaug State forest, which is nearby in eastern Connecticut where I was working. And I just started walking a traverse. And I was going up over one after another, and another and another stone walls, and it just struck me that day. What are these things? Why are they the size they are, the color they are, the mass they are, the continuity they are, the pattern they are... all those questions that a trained scientists would ask about them.

CURWOOD: So, stone walls are all over the region. Who made these walls?

THORSON: If you're talking about the abandoned field farm landscape of the 19th and 18th century, then almost entirely, it's the people who own the land and were using money from the land to do things. If you're talking about the Gilded Age or 1920s or Edwardian or even late Victorian, when you get past the zenith of New England's agriculture, then most of the walls are being built by immigrant work parties for very low pay, but the money came from somewhere else. And so you end up with a nice, tidy, long, uniform degree of construction that an architect might recognize. The walls that I like are the ones built by the people on the land, because there's an ecological component to them, a human ecological component.

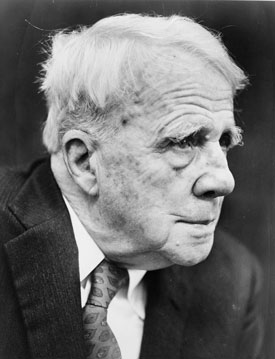

Robert Frost (1874 – 1963) was a prolific American poet whose work included, “The Road Not Taken,” “Fire And Ice,” and “Mending Wall.” (Photo: Walter Albertin, Wikimedia Commons via U.S. Library of Congress)

CURWOOD: Let's go up the wall a little further, because I want to ask you about the ecology of what's in these walls today.

[SOUNDS OF FOOTSTEPS]

CURWOOD: So, many of these stone walls obviously were abandoned. This farm stopped farming livestock probably a century and a half ago. But you say that these are important parts of our ecosystem. What makes them so important in the ecosystem?

THORSON: Well, if you look at the stone wall right in front of us, you don't see any surface moisture, and you never will, unless it's raining or you're getting snow melt. These are very, very dry. They're effectively deserts. They're hollow, open spaces that animals can live that don't exist on the woodland floor. It's also a corridor. If you wanted to move along your territory and you were a fox, or you were a squirrel, or you were a cat, a bobcat or a fisher cat, you could cruise along the top of the wall and see more. You would be more exposed if you were a predator. If you were prey, you'd likely scurry along beneath the edge of the wall, and you get cover. So, as boundaries, as corridors, and as habitat, stone walls have a life all their own.

CURWOOD: And the geologic story here?

THORSON: Well, if you accept that human beings are geologic agents - which I do, being the strongest one - then they're part of that geologic story. If you were to just say, OK, what happened here since glaciation, we're about it. I mean, glaciation and then human activity, those are the two dominant events that have happened here on the landscape to shape and change the landscape. It's not to say that other people didn't live here for a long time, but these are the main shapers, and one is glacial in origin, climatically driven, and one is human in origin, economically driven.

CURWOOD: Thor, talk to me about the famous stone walls here in New England.

THORSON: I think the most famous one is Robert Frost’s Mending Wall, because people in Iowa know about that wall. People in Florida know about that wall, and it's one of New England's real treasures, that poem. And I've been to Derry a number of times, and I've talked there and explored and investigated the mending wall. It turns out the Mending Wall is a combination of two different walls. That poem was written when Frost was in England. It was one of his earliest ones and he's writing it from memory. And he garbled together two things, whether intentionally or not, that are really important to the New England psyche. One of the ideas, the maintenance, structure, order, you know, keeping stone on stone, mending the wall, and the other, of course, is territorialism, the fences that we erect between ourselves in our communities and otherwise. And he really dwells nicely on both of those. The Mending Wall, the poem, has both the boundary wall and the precarious stones as round as balls are loaves, but the actual walls on that property are very distinct. One is a boundary and one is a place where you can hardly stack a stone, and they don't map on top of each other.

CURWOOD: Philosophically, what do you think if his point that there's something that doesn't like a wall?

THORSON: That something is all of nature itself that doesn't like a wall, because a wall is created with intent by human beings. For whatever reason, it's going to come down, and to me, that's nice. I love the old, abandoned, lichen-crusted closed canopy forested walls in the age of the Anthropocene because they tell us that in some places, the Anthropocene impact is already being re-healed. And the wildness seeking person in me likes seeing that.

Robert Thorson (left) and Host Steve Curwood examine a rock from a wall in New Hampshire. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So some would say that stone walls helped win the American Revolution. Why would they say that?

THORSON: The number one reason that they would say that would be because the colonists, the ragtag Minutemen, used the walls for cover, and they were very hard to pick off by the British marching in columns down the road. On a deeper level, you could argue that the walls are expedient parts of the farms that gave the beef and the butter and the bacon and the bread that fed those armies. We know that armies don't march on an empty stomach. Also, I think there's a territorial boundary element. I think that just seeing a stone wall, makes you feel more secure, it makes you feel enclosed. It makes you feel contained. It makes you feel separate. So, you could say that, at a psychological bedrock level, they helped with the idea of separateness.

CURWOOD: Robert Thorson is a professor of geology at the University of Connecticut. Thor, thanks so much for taking the time with us.

THORSON: It's been a pleasure. What could be nicer than being in the woods with surrounded by stone walls?

Links

Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth