Seas Rising Faster With Antarctic Melt

Air Date: Week of June 22, 2018

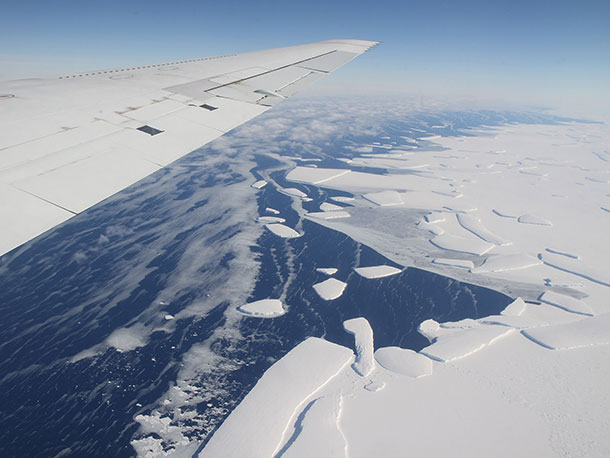

A new study in Nature finds 200 billion metric tons of ice are melting off Antarctica every year, a number that has tripled in the last decade. (Photo: NASA/GSFC/Jefferson Beck, Wikimedia Commons)

A new study in Nature finds Antarctica is now shedding more than 200 billion metric tons of ice every year, mostly from its western ice shelves. That’s three times the melt rate of just a decade ago, and climate disruption is largely to blame. Lead scientist Andrew Shepherd explains for Host Steve Curwood why the melting near the South Pole leads to more sea level rise, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, where the most people live on Earth.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Scientists have done a good job finding the links between human activity and climate disruption, but they tend to underestimate the actual rates of change. The latest unwelcome surprise comes from data that shows Antarctica is melting much faster than previously suggested, as much as 200 billion tons of ice loss each year. As a result, they say the rate of sea level rise has tripled over the past decade, with profound implications for coastal cities. Andrew Shepherd of the University of Leeds in the U.K. led a team of 80 researchers from around the world, including NASA, who gleaned the data from satellite and Earth observations. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SHEPHERD: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, 200 billion tons. That's a pretty big ice cube. How much ice is that really?

SHEPHERD: So, you could visualize it as an ice cube if you like, and it would be about six kilometers either side, so a very large cube of ice. The practical way to visualize it is by spreading it out in the oceans because that's where it's going in the end, and today it's quite a small layer on top of the oceans – it's about 0.6 millimeters each year into the oceans.

CURWOOD: What percentage of the global sea level rise is that right now?

SHEPHERD: The recent assessment of sea level rise is for about 3.4 millimeters per year or about a fifth or a sixth of the total sea level rise. But in context, it used to be a much smaller proportion and the contribution is on the rise, and that's the thing that's of most concern.

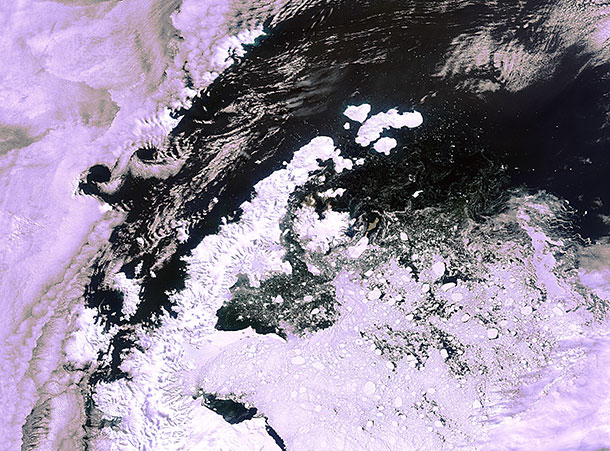

The scientists used satellite data for their research, looking at factors such as changes Antarctica’s shape over time, as well as changes in the earth’s gravitational field. (Photo: ESA, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So, this is all very concerning. Tell me, I understand that sea level rise affects some areas more than others. Why is that?

SHEPHERD: It depends where the sea level rise comes from. So, if ice is lost in the southern hemisphere, that causes sea levels to rise more in the northern hemisphere because of the way the Earth's gravity balances it out, and vice versa. So, this particular story affects those of us that live in the northern hemisphere a little bit more.

CURWOOD: And how much ice is there in Antarctica? As I recall there's a couple of miles of it right at the South Pole.

SHEPHERD: Yes, I mean, most of Antarctica is pretty, I guess you would say, inert. It isn't changing very much. There's a very, very large ice sheet in Antarctica, so the easy way to conceptualize it is the amount of ice in Antarctica would amount to about 58 meters of global sea level change if it were to all melt. So that would be an extra 58 meters on to sea levels, and that hasn't happened for a very long time. But that's one way to visualize how much is there.

CURWOOD: You're saying that there's a round number of some 200 billion metric tons of ice that seems to be coming off of Antarctica every year. How did you get those numbers?

SHEPHERD: So, we have been able to use about a dozen different satellites that have been in space at some point or other since the early 1990s, and we have a few different techniques for measuring changes in Antarctica and also in Greenland. We can measure the change in the shape using satellite altimeters.

They’re instruments that can measure the height of Antarctica and how that changes over time. We have a bunch of different instruments that can tell us how fast the glaciers are flowing, some of them really sophisticated and some of them just taking photographs from space that we compare over time, see crevasses moving along. And then we have a new sensor – relatively new, it's been in orbit for ten or 15 years now – which measures Earth's gravity field. And changes, believe it or not, changes in the ice loading on planet Earth at the poles do affect the microgravity that the satellites sense in space. And so we can use those measurements as well to calculate how much ice is changing.

CURWOOD: Now, your study said that this rate of melting has tripled over the past decade. What information do you have about how that is happening?

SHEPHERD: So, when we look at Antarctica, we see that in east Antarctica, which holds most of the ice, there has been little change, so east Antarctica is by far the biggest part of Antarctica. It's where the South Pole is. That ice is actually sitting on an island that's above sea level, and we're pretty confident that the reason it hasn't experienced any change is because it's isolated in the main from the oceans and we think that the oceans are the way the Earth's heat is being delivered to Antarctica. The atmosphere in Antarctica is very cold. It seems obvious, but it is cold.

Most of the ice in Antarctica is on land, but on its western side where glaciers flow into the ocean there are large floating ice sheets. As global temperatures rise due to climate change, the West Antarctic ice sheets encounter warmer waters that promote melting. (Photo: Ronald Woan, Flickr)

Never really gets above freezing except in some very, very isolated places. With an average temperature about minus 40 degrees Centigrade you would need to heat the planet a lot to change the ice via the air. But the ocean surrounds west Antarctica, and the ocean is already above freezing -- that's why it's wet -- and so you can deliver heat quite effectively through the oceans if you change their temperature. And we think that all the ice loss, well, we know all the ice loss is happening in west Antarctica, and we think it's due to the ocean being too warm there.

CURWOOD: Please compare for me Antarctica’s ice loss to the rapid melting we've seen from Greenland.

SHEPHERD: It has been very clear that Greenland has lost more ice each year over the past 20 or 30 years, and that is largely because Greenland is farther from the North Pole than Antarctica is from the South Pole and sits in a relatively warmer climate. So, if you visit Greenland in summer, it's above zero temperature and at times it gets up to quite warm temperatures. 20 degrees Celsius is not uncommon. And so Greenland loses a lot of its ice through melting, not just through glaciers calving icebergs into the sea. And so, this argument about small changes in Earth's planetary temperature and how they affect an ice sheet is different for Greenland. If you raise the planet's temperature by one degree Centigrade, in summer you melt more ice from Greenland, and that's what's been happening over the past 20 or so year. In Antarctica, it was a very different story. We didn't think that the ice was melting from the surface – it still isn’t. But we also weren't sure whether heat could be delivered to Antarctica via the oceans either. And that's because Antarctica is situated south of a part of the planet where there is an uninterrupted ocean. So, if you look between Antarctica and the southern tip of South America, there's a band of ocean there which has a very, very active current traveling around it, and people used to think that that ocean was impervious and wouldn't allow heat changes elsewhere on the planet to be transmitted across it. That doesn't seem to be the case anymore.

CURWOOD: Andrew, how did you feel when you got these findings?

SHEPHERD: I think we were definitely – and it's not just me, as we have a team of 80 or more people involved and many more involved in the space agencies – we were all very surprised. We didn't expect Antarctica to jump up there in terms of its ice losses and start to rival Greenland, but that's happened. And part of the reason that we're reporting Antarctica now is because it's an important piece of information, such a high profile piece of information, we think that people need to be aware about it.

As sea levels rise, the frequency of floods is expected to increase and the Antarctic melting means the Northern Hemisphere will be more affected by these changes. (Photo: Joe Shlabotnik, Flickr)

CURWOOD: So, what's the takeaway from all of this research, Andrew?

SHEPHERD: So, the takeaway message is that unfortunately Antarctica is not isolated from the effects of climate change, and it's experiencing climate change, and so we should look to the projections for sea level that allow for that to happen, and they're not the ones that we're currently thinking about right now. We definitely did underestimate what would happen in the present five years when we looked at this problem five years ago. So, we need to be thinking about an extra 20 or so centimeters of sea level rise in the northern hemisphere if the continent of Antarctica continues to follow the trajectory that it is actually on now. And that will be a number of significance to urban planners. It may not sound a lot to people at home, but it will affect the frequency with which coastal areas flood today.

CURWOOD: What keeps you going despite all these daunting findings? This is a threat to civilization itself.

SHEPHERD: Ah, well – doing nothing is the threat and knowing nothing is the threat. Knowing something is definitely not a threat. Knowing something is being prepared for action, and I've been very pleased about the impact that this work has had. People are interested to learn about it and I hope that that means that people have listened and heard the message, and the politicians who are ultimately responsible for changing the course of our futures will act on that. So, I don't see it as a bad news story. I think it's really good news that we're able to tell people that they need to be concerned. Because we can act.

CURWOOD: Andrew Shepherd is a Professor of Earth Observation at the University of Leeds in the U.K. and directs the Center for Polar Observation and Modeling. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SHEPHERD: Thank you for having me.

Links

The Washington Post | Antarctic Ice Loss Has Tripled

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth