Rough Riding for Wild Horse Country

Air Date: Week of October 20, 2017

Wild horses run free after being released back onto the Nevada range by the Bureau of Land Management during a roundup or “gather” in February 2017. (Photo: Kyle Hendrix/BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

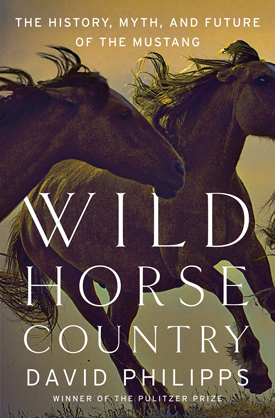

Tens of thousands of wild horses, or mustangs, still roam the vast, undeveloped public lands of the American West. Cattle ranchers argue the horses’ booming population threatens their livelihoods, and the health of the rangeland. But the public generally opposes any plans to send wild horses to slaughter. Author David Philipps’ new book, Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang tells the story of a tough survivor that defies the efforts of cash-strapped government agencies to control it as it continues to live up to its reputation as “the one that got away.”

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLoYFvbR0XY

[MUSIC: Roy Rogers, Don’t Fence Me In]

The King of the Cowboys there, Roy Rogers, with the stuff of romantic legend, the freedom of the endless fenceless prairie, the cowboys, and doggies and wild horses by the millions running free. As the Wild West was tamed, mustang numbers declined and some were even rounded up for meat. A public outcry stopped that and now the wild horse herd is growing, to more than 70,000 at the latest count. A book, "Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the mustang", explores the controversies around this iconic animal and its future. David Philipps is the author and he joins me now from Colorado Springs. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

PHILLIPS: Thank you for having me on.

CURWOOD: So, your book is all about the mystique and the reality of the mustang. Tell me why do you think Ford Motors took the name “Mustang” for the first muscle car that they built back in the 60s? The iconic one.

Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang is David Philipps’ second book. (Photo: courtesy of W. W. Norton)

PHILLIPS: Well, so this goes back to what we think of the mustang as being. In a way, it's the most American animal. It's an immigrant. It comes from no sort of aristocratic background. It came over here as a nobody and sort of got what it got through grit, which is exactly the story that we tell of ourselves. You know, the old “up from the bootstraps” type of stuff. And so, when they built a car that was small, dependable, and fast it embodied a lot of the things that Americans at the time thought of the mustang.

CURWOOD: Of course, the mustang officially an immigrant but actually in your book you say it wasn't really an immigrant if you look back in paleo history.

PHILLIPS: Yes, so that's what's interesting about the debate over wild horses. They really spent most of their ancient history developing in North America, about 55 million years. They spread all over the world from where they developed here, and then about 10,000 years ago they disappeared right about the time that humans crossed the land bridge into North America. Then they returned with the Spanish and spread back all over the place, and the question is, if an animal was here for 55 million years, disappears for 10,0000 and then comes back, is it invasive or is it native, and should we be surprised if it spread so quickly over an area that it had evolved to thrive in?

CURWOOD: By the way, where does the name “mustang” come from?

PHILLIPS: Mustang is the word that the Spanish used back in the days when they were first moving into Texas, they had a word “mesteño” meaning a stray horse that belonged to the herders. The BLM and certainly a lot of ranchers will say these wild horses out here, “They aren't mustangs. They are just a bunch of feral ranch strays that got away”, and that is true. If you look at the genealogy of the wild horse, it's like us, it's a mix of everything. It is Spanish horses that have been here for hundreds of years. It is ranch horses that may have escaped in the 50s, and so it was always a name that meant essentially “the ones that got away”.

CURWOOD: So, you're not actually a horse guy yourself. You're not one of those folks who spent more than, you know, a few hours, I guess, in your lifetime on a horse. Why write a book about the mustang?

.jpg)

A helicopter rounds up horses in the Bureau of Land Management’s Stone Cabin Herd Management Area in Nevada. (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: Yeah, I'm almost embarrassingly not a horse guy. All those things, like I don't know what withers or fetlocks are anything like that, but what I am is I'm a guy who grew up in the west, who loves the untamed and open nature of it, and so in a lot of ways, I saw the wild horse as an attempt for us to try to preserve that idea through federal legislation, and I saw how mixed up it got, and so I thought to myself, “OK, if you can understand the horse and what we tried to do with it and how it failed, you can probably understand a lot about how we feel about the wild parts of our country and how we can better approach trying to let them thrive”.

CURWOOD: So, why is it the fact that wild horses are roaming the West today is so contentious?

PHILLIPS: A lot of it comes down to numbers. How many horses should we have in the west? The government says sustainably we can have about 27,000. Any more than that and they are not only going to damage the range, but they're going to compete with the cattle ranchers and sheep raisers that are already there, and those folks have a very old claim on the land as well. The problem is that the government has never been able to control those numbers. In fact, in a lot of places horses are at two or three times the prescribed amount, and if you're trying to raise cattle and make a living that way you can understand that that impact would make you pretty angry. And so, in a way, the wild horse has become this divisive symbol. It once was sort of this universal symbol of American grit but now for a lot of rural communities it is the symbol of federal interference, of crazy ideas from city slickers that are imposed on them. That divide between urban and rural is certainly there, and it affects policy in a big way.

Wild horses from the Reveille Horse Management Area enter the wings of a trap during a February 2017 gather. (Photo: BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The mustang is famous for being such a tough horse, and when the Spaniards brought the horse back to North America, Native American tribes got a hold of them. How did the introduction of the horse by the Spanish change Native American tribes?

PHILLIPS: Wild horses were a sea change for tribes. Once they were stolen from the Spanish and spread through trading and stealing and warfare, they very quickly reached almost every tribe in the west and changed everything. They changed how they hunt. They changed how they moved. Because they were moving more often they changed what they lived in. All of the sudden the tepee became, you know, the dominant form of housing. It changed their songs. It changed their religion. It changed their view of the universe literally. The Navajo say that the sun is pulled across the sky by a chariot of four horses. It created entire new tribes, tribes that didn't exist before. The Comanche were a nothing part of the Shoshone, and then they decided to get horses and became one of the most powerful and feared tribes in the entire west, able to hold off both the American and the Spanish empires at once and claim most of the Southern Plains.

CURWOOD: It is interesting, you point out that at the Battle of Big Horn, General Custer showed up with a shiny thoroughbred from Kentucky and the Native Americans had mustangs and the surviving horse from that was….?

Wild foal and mare in Cold Creek, NV. In the absence of population control, wild horses are quite successful at raising young on the range. (Photo: James Marvin Phelps, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

PHILLIPS: A mustang. In fact he was a mustang who had been shot several times by arrows, and yet had a long life afterwards, and that, is really the story of the mustang in the west. There are stories from Little Big Horn or folks like Buffalo Bill of riding mustangs 100 miles at a clip and having them outrun some of the best horses. These are horses that natural selection has acted on for centuries. Anything that wasn't going to be really tough got weeded out a long time ago, and so what is left is almost the perfect horse. It may not look like much but, man, it can run.

CURWOOD: David you open your book with a visit to, well, what we think of as a round up. Briefly tell me that story, what you saw and how you felt.

PHILLIPS: Every year, in order to keep the wild horse population at a set level, the federal government removes thousands, sometimes more than 10,000 horses through helicopter round ups. The way that works is one or two helicopters will sweep across some desert valley and bring the horses into a funnel-shaped corral. When the helicopters bring them in, you see these herds pushed together and galloping, and it’s really something out of a movie, beautiful multicolored bands coursing across the sage, and then what's amazing is how quickly, once they're pushed into these corrals, these circular corrals, they sort of stop and stand around and are pushed onto semi-trucks, and the wildness is gone. It's a very efficient operation, and in one round-up, sometimes they remove 500 horses.

CURWOOD: So, what happens to these horses after they've round them up, and why are they running on them up to begin with? I mean they're wild horses, why not let them run?

PHILLIPS: The reason that the federal government rounds up wild horses is because the Wild West is not what it once was. We have scraps of it and on those scraps where wild horses live, the federal land managers have decided, well, those scraps of land can only support so many horses. That is sort of the crux of the problem of wild horses because when we remove them, we don't know what to do with them. The plan has always been to remove horses and have them adopted by people. Those people can then train the horses and use them as saddle horses, but we have never had enough people adopt, to take care of the horses that are removed, so there's literally a government surplus in wild horses.

In the 80s and 90s, and to a certain extent in recent years, the Bureau of Land Management has quietly looked the other way while people bought them and sent them to slaughter, and that's happened to tens of thousands of horses. As the public figured that out and demanded that it stop, the BLM has instead taken those extra horses and put them into what it calls “the holding system”, and the holding system is this vast network of private ranches that they pay to store wild horses at a cost of about $50 million dollars a year, making some big, already wealthy ranchers very rich.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this a program of horse incarceration?

.jpg)

A lone mustang on the open range in the Stone Cabin Herd Management Area of Nevada (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: The holding system is certainly not the wild. They are separated by sex in these huge pastures. Now, I've got to say these pastures are great. Most of these ranches are in the Flint Hills of Kansas and Oklahoma, and they are beautiful, some of the most lush rolling grassland in the world. In a lot of ways they are much better forage than these horses could ever have out in wild horse country. I don't know if I would call it incarceration, but maybe purgatory. When I went to see these big holding pastures, the thing that struck me is, it was sort of like if you took a bucket from the Colorado River, and put it to the side, you still have the water there but the wildness, the life, is sort of gone, and in a way that that's what's there. They're waiting around to die.

CURWOOD: So, how well is the federal wild horse management program working today?

PHILLIPS: At this point the wild horse program is in a crisis. It has so many horses in storage that it can't afford to run the rest of the program. It's sort of fallen into an addict's dilemma, where an addict might want to go to rehab but can't afford it because they're spending all their money on drugs. The BLM, I think, wants to develop alternatives. The BLM wants to look at different ways that it can control horse populations besides rounding up, them up with helicopters and storing them, but it doesn't have the money because it's too busy rounding them up with helicopters and storing them.

So, now that program is grounding to a halt. They are spending so much money on storage that they can't really round up horses anymore, and so they are leaving them on the land. The government says that we should have about 27,000 horses on the land. That's what they think is sustainable over time. Right now we've got about 75,000, and it's going to go up and up because they don't have money to address the problem. So the train is about to come off the rails, and the question is, when it does, what will we do?

CURWOOD: So, David, all right, too many horses. What about birth control?

Wild horse advocate TJ Holmes, with her dart gun slung over her shoulder. She uses it to administer the birth control PZP to wild mares. (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: Actually the BLM is doing this, and it works surprisingly well. They have a drug they use called PZP delivered by a dart that keeps mares infertile for one year. They have had this drug for 30 years. They have used it in very, very small numbers and said almost every year that they are going to roll it out in big numbers because they think that it's a great solution. But really they are stuck in a place where they don't have money to use the fertility control drugs because they are too busy storing horses. The only places that they're using fertility control drugs effectively right now are places where local volunteers have set up a program. They're doing the darting themselves, often middle-aged horse aficionados who know nothing about this but have taught themselves, and they are controlling those populations while the BLM is busy doing other things.

CURWOOD: Now, in other places - I'm thinking particularly of France where they're quite proud of horse on the menu - many other places actually send horses to slaughter who can't find an economic or an ecological niche for themselves. Why don't we do that in America?

PHILLIPS: Well, there are a number of people who have suggested that the way out of the wild horse dilemma is to just allow them to be slaughtered, and I think that, practically speaking, simply in terms of how easy it would be to do, it is maybe the easiest solution unless you consider the politics. I don't think that any in Congress, even really conservative members who have voiced support for this, would vote to slaughter tens of thousands of horses in storage because there would be an outcry. It's become so politically polarized that we don't even have horse slaughterhouses any more in the United States. There are number of American horses that get slaughtered but they're all exported to either Canada or Mexico. But I think one of the reasons for that is that we have this cowboy myth and the myth of the horses' companion. You know, we see it as a companion animal and so we would no sooner eat a horse than we would a dog.

CURWOOD: One of the most intriguing parts of your book, David, is your final chapter when you bring forth a potential, perhaps more wild solution for controlling wild horse populations, and that's bringing back mountain lions to parts of the west that the mountain lions have vanished from. Why do you think this could work?

Reintroducing mountain lions to some remote parts of the American West holds promise for controlling wild horse populations. (Photo: cohenHD, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

PHILLIPS: First of all, let me say that, if there's any wildlife managers listening right now, they have probably just spit out their coffee and are rolling their eyes because there is an orthodoxy within the wildlife management world that mountain lions do not eat horses. They can't, and they won't, and therefore to even talk about it marks you as somebody who doesn't really understand the issue.

So, that's where I started until I started actually reading the scientific literature on it, and over the decades lots of people have studied mountain lions in the west and lots of people have studied wild horses in the west and often times their research has been interrupted because too many mountain lions were eating too many wild horses. It happens over and over and over again, and it always happens in the same way. During the spring and summer when horses have their young, and they go to drink at a desert spring, the mountain lions will bound out of the brush and take down a foal, and sometimes they're taking down a foal a week, and this can have real impact on wild horse population numbers. You know, it's almost like the, the "Mutual of Omaha" movies that you see of the of the Serengeti where that where the zebra goes to the watering hole. This is our American Serengeti still at work.

CURWOOD: You talk about a person you met in the course of this question of mountain lions and horses. I believe his name is John Turner.

David Philipps is a Pulitzer Prize-winning national reporter for the New York Times. (Photo: Mark Reis)

PHILLIPS: Yeah, John Turner is a long time wild horse researcher, a biologist who's been studying horses out on the border of California, Nevada for decades, and what he realized is that even though the Bureau of Land Management was denying it was happening and no one had ever recorded it, this small population of mountain lions, maybe about six or seven, was holding a population, a herd of wild horses in check in this one valley and had been doing so for decades. For me, this was really exciting. This was a way to preserve the wildness that we wanted in the first place. When we preserve the animal wild horse, what we really wanted to preserve was that idea of liberty, of toughness, of independence, and we haven't done it because we left the wildness out of the equation.

CURWOOD: David Phillips is the author of "Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth and Future of the Mustang". David thanks so much for taking the time for us today.

PHILLIPS: Thanks for having me on.

Links

Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang

About the BLM’s Wild Horse and Burro Program

National Geographic: “Can Fertility Control Keep Wild Horse Herds in Check?”

John Turner’s research on predation of wild horses by mountain lions

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth