Climate Change and the National Parks

Air Date: Week of June 3, 2016

Sea-level rise is a major threat to coastal parks including Everglades National Park (Photo: Erik Salard, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

The director of the National Parks recently said that climate disruption represents the greatest threat to the integrity of the park system. National Park Service scientist John Gross tells host Steve Curwood how park managers are rethinking many of their management strategies.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. Climate change is not just incinerating boreal forests – it’s also presenting new challenges to one of America’s most beloved icons - the National Parks. Indeed, park service director John Jarvis recently said climate disruption represents the single greatest threat to the integrity of the parks that we have ever experienced. And this is causing a wholesale rethink of planning for the future of the parks. John Gross is an ecologist busy at work as part of the National Parks Service’s Climate Change Response Program, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, John.

GROSS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, tell me what kinds of impacts of global warming immediately come to mind in our national parks?

GROSS: Well, we're seeing all kinds of climate change impacts throughout the system, so some of the most obvious, for example, are sea level rise impacts on coastal parks where we're seeing erosion of cultural resources, of beaches and these sorts of things. In our parks in the northern areas, for example, in Alaska, we're also seeing melting of permafrost, park staff are having a very difficult time getting into some parks because they need either the lakes to be thawed and have no ice on them or else to be sufficiently frozen that they can land airplanes, but now they're seeing longer seasons of slush on the lakes and you can't land an airplane on slush. In addition to that, parks are seeing the kind of impacts that the forests are. We're seeing increasing fires that are more severe and larger. In many of our western parks you'll see a lot of trees that are affected by pine beetle and are brown, and those occur in Rocky Mount National Park, for example. We have extensive tree death up in Yellowstone with white bark pine and other species. The seasonality of things are changing. So park visitors are actually responding to climate change also and they're showing up earlier in parks, and in some cases staying later. So the impacts are really extremely widespread all over the parks.

The USGS is studying the impacts of climate change in Glacier National Park in Montana (Photo: United States Geologic Survey)

CURWOOD: So how's the Park Service responding?

GROSS: The Park Service is responding in a variety of different ways. Initially when we started, our primary means was to educate people in the parks and to increase our interpretation of climate change impacts that were being seen on the ground. So that's training park managers as well as those of us that service many parks. We’re doing a lot of mitigation efforts using hybrid cars solar voltaic arrays to produce solar electricity for parks, reducing our environment footprint. So there’s a whole series of responses from on the ground all the way up through training and working with staff.

CURWOOD: How's it changing the management of the parks service now that you're thinking a lot about climate change?

GROSS: Well, we're really changing the way that we're looking at planning. So in the past, our planning was designed to identify, for example, one desired future and we now recognize that there's a broad range of climate projections and that doesn't work, and so we're trying to develop scenarios for our parks where we look at two or three or four different possible and plausible futures, based on scientific projections of climate, and then we use those to try to find strategies that are robust. We recently released a report called "Revisiting Leopold" that carefully examined our management strategies, and their first recommendation was that the overarching goal of the park service should be to steward resources for continuous change.

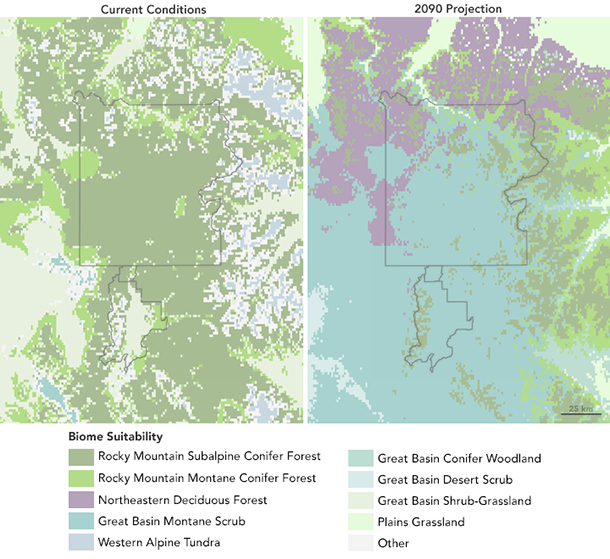

Now, that's a dramatic departure from the past where the previous Leopold talked about maintaining vignettes of the American wilderness, which essentially was before European occupation. So we've recognized that the fundamental underpinnings of the way that we manage parks has to change with climate change, that it's no longer trying to maintain a system as it was 100 years ago. That's just not possible, so we're looking much more towards broad-scale effects and allowing species to move into and out of parks to adapt to climate changes.

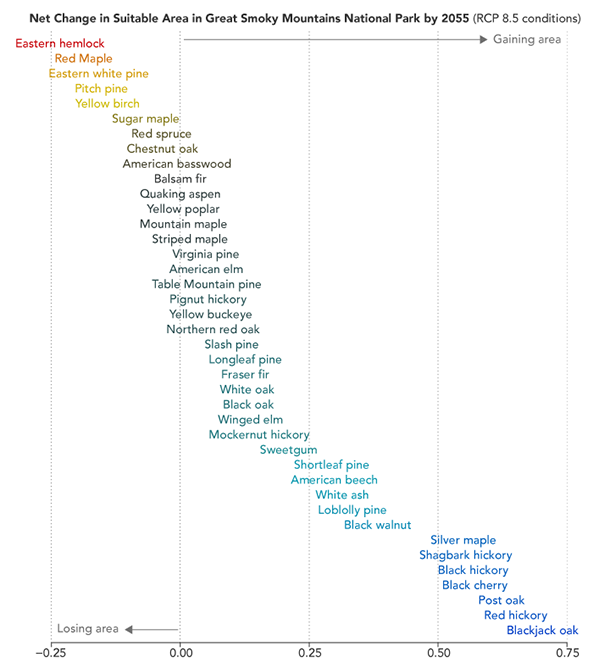

Climate change will affect each species differently. While warmer conditions are undesirable for some trees, they are more desirable to others. Over time, forest compositions will change as saplings slowly migrate with the changing conditions. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory chart by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project

CURWOOD: Yeah, back in the day there was something of an attitude among conservationists that, you know, just put a big fence around this big plot of land, protect it from development, but of course climate change doesn't pay attention to any kind of fence.

GROSS: No, it doesn't and that's really one of the biggest challenges that we face, that our park boundaries or not changing, but now climate change is happening so rapidly that animals need to move, they can't adapt to the climate change in place, and so those areas that are suitable for species are moving, but the park boundaries are not and that's why we’re looking so much at connectivity of parks and working much more with their neighbors through the landscape conservation cooperatives, trying to recognize the park served essentially isolated and so we need to increase the conductivity between parks and the surrounding landscapes so animals are able to move. We've got the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative, there're some major migratory corridors from pronghorn and mule deer that inhabit the area around Great Teton and Yellowstone National Park, and they migrate to the south towards the Red Desert. And it's not just western parks I was recently at the C & O canal, and the C & O canal was a very important linking landscape between a whole series of state forests and other natural areas along the Potomac River near Washington DC. So these corridors and conductivity between natural habits extremely are important all throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

The Pine Bark Beetle is one of the major threats to Western forests (Photo: Simon Fraser University, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: You know, animals of course have wings, they have legs, they can move to other locations. Trees move a lot less rapidly, generally a seed can move a little bit more in a generation and then move a little bit more. So, how's climate change affecting the composition of trees within our national forests?

GROSS: Well, we're already seeing some changes. There was a study that was just published from California that showed that in the Sierras there's a number of tree species that are moving up the mountains, moving up in elevation as it gets warmer. The climate models are projecting that the areas where trees live now are going to change dramatically. Some of them, it turns out have been there for thousands and thousands of years and they're likely to be less affected, but a lot of the dominant tree species will be strongly affected by climate change. These changes are unlikely to be gradual changes, that what we'll see is that mature trees are generally pretty resistant to climate and they'll stay there until there's a big fire or some other disturbance that kills a large area. So we're very concerned about when that happens the tree species that are probably suitable for that area are not likely to be there, and so there won't be seed sources. So we're looking right now to try to project what kind of species might occur and be thinking about do we need to provide corridors via prescribed burns or other methods that might facilitate these movements of species.

The warming world is changing when wildflowers bloom in National Parks like Mt. Rainier in Washington State (Photo: Jim Culp, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, sea level rise could be a serious challenge for some of our national parks. I'm thinking of the Assateague Island National Seashore Area where all those ponies on that island are. Of course, the Everglades are right at sea level. What's the planning at the Park Service about those places?

GROSS: Well, they're changing quite a bit. With Assateague, for example, traditionally we had firm structures that were on the shorelines there, and for now, what we've done is we've for example are paving roads was crushed corals in other areas rather than something like asphalt so we know that as sea level rises those facilities will either be destroyed or need to be moved. So we also have portable buildings that we can move. In terms of the land itself, we're recognizing that some of those beaches and some of those dunes are not going to exist in the future. Similarly, with Everglades most of that park is extremely close to sea level and the projections of sea level rise are that the area of that park is going to decline dramatically. Right now, we don't have any plans in place to reduce the area of the park or change the boundaries for example, but it is affecting in a fairly substantial way, our planning for facilities and so we're not siting facilities in areas that are projected to be under water in the next four, five decades.

Climate change can make an area less suitable for some trees and plants—and more suitable for others. Within several decades, the primary vegetation found around Yellowstone is predicted to undergo substantial transformation. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project)

CURWOOD: The National Parks about 100 years old. If you were to look ahead another century, what role do you see National Parks playing over the next hundred years while we are trying to preserve biological diversity at a time of rapid change, climate change?

GROSS: I think the parks absolutely have a critical role to play in that, in a variety of different ways. We have on the order of 400 million visitors per year, and so I think the parks are really a very important educational role for people to tell them about climate change, to interpret the changes that we're seeing now. They also have an extremely important role for preserving biodiversity. We have some of the finest landscapes in the world in our national parks and so I think the parks will continue to play all of the roles that they play now in terms of sites that people want to visit for aesthetic or recreational reasons, for preserving biodiversity and for educating people from around the world on what's happening with their natural environments.

CURWOOD: John Gross is an ecologist with the National Park Service's Climate Change Response Program. Thanks for joining us, John.

GROSS: Thank you, Steve.

Links

Read more about how climate change is impacting trees in National Parks

National Parks Service Climate Change Response Program

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth