London Fog: The Biography

Air Date: Week of March 25, 2016

London Bridge on a foggy day. (Photo: stu mayhew, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Cities have unique signatures, and for London, that’s fog. A century ago, acrid, corrosive soot-laden smog killed thousands and shrouded the city in darkness. Yet some Londoners felt affection for the fog; they called it “the London Peculiar”, and it featured in books, art and on the screen. In “London Fog, The Biography”, Christine Corton profiles the heyday of this miasma and she tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer what it took to clean the air up.

Transcript

[MUSIC – A FOGGY DAY IN LONDON TOWN]

CURWOOD: Rome is the eternal city. Paris is the city of light. And London has fog.

[MUSIC – A FOGGY DAY IN LONDON TOWN, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ek1KFID0gSc]

And it’s not just historical – in just the first week of 2016 London’s air exceeded its annual limit for the toxic gas nitrogen dioxide. But it used to be far, far worse. For days at a time, foul, stagnant, smoky air would settle over the city, turning day into night and sickening thousands. And yet some Londoners had a strange affection for this environmental hazard, and the London fog’s murky shadow was reflected by writers and painters and film-makers. Well, now there’s a new book that examines these legendary “pea-soupers” from writer Christine Corton called “London Fog: The Biography.” And we sent our resident British ex-pat, Helen Palmer, to talk to her.

PALMER: Christine Corton, you're the author of "London Fog: The Biography.” I'm interested into why you decided it should be a biography rather than, say, a history.

CORTON: Because I wanted to see it in terms of it being born and it terms of it being killed off, dying. I wanted to see it having a kind of personality of its own. It was loved by Londoners as well as loathed, and that was why it was called all these names. It was named London Particular in a very affectionate way because Londoners wanted to show how proud they were of it. After all, there is an upside to London Fog - smoke. If you've got smoke in the air, it means you got employment and industry, and it means you can have an open fire to warm yourself. But Londoners were essentially quite proud of it. They felt it created a distinction for them as a city.

Most Londoners heated their homes with coal fires in the 19th century. (Photo: Danny Chapman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: Let's have you read a piece from the book. There's a passage I particularly like on page 245. It's a quotation from The Times from December 1924.

CORTON: Yes. OK.

The London Particular is a true London pride. It is unique, no less than is London gin or London wit. Other places may be able to show a mist or so. Only London has fog. And Londoners are secretly proud of it. Only the largest shareholders in gas and electric light companies, the launderers and perhaps the soap and face cream trades dare to confess their joy in a thorough London Fog, but every Londoner feels, on such a day as yesterday, the distinction of being a citizen of so singular a town. Fog breaks the monotomy of life. It shows itself familiar surroundings in a new and an artificial light. It gives us something to talk about, and those of us who live to see the sensible thing done at last, and the London particular deprived of its artificial foulness, we'll find us ourselves sighing for the good, old days.

PALMER: That's a lovely piece of writing, but in fact, the fog that they're describing was particularly awful. It was full of soot, it was full of - what?

CORTON: Well, it was full of particles basically, from uncombusted coal. So it was very visible. It would turn the color of the fog green, yellow, mainly yellow, black sometimes, but it was very dangerous to breathe in, and people would quite often cough up black spit which showed what they were actually kind of taking in, digesting, and you could suffocate. If your lungs were weak, if you were elderly or very young, you could actually suffocate because you couldn't actually get rid of these rather nasty particles from your lungs.

Claude Monet captured the London fog in a series of impressionist paintings on a visit to the city. (Photo: Musée d'Orsay, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

PALMER: And in fact the fogs did bring much higher mortality when they were really bad.

CORTON: Yes, the 1952 smog which is probably the one most people are aware of, killed possibly about 12,000 people. It’s very difficult to kind of give statistics because, of course, government said well they would've died anyway because they already had lung issues, they had heart issues, or they died from the flu. Quite often governments would blame colds or flu, but nowadays we reckon the '52 smog probably killed about 12,000 people.

PALMER: London's a big city, but still, that's a lot of people.

CORTON: It is, especially when you consider that that’s a week's worth of fog. Of course they didn't die during that week. They may have died two or three months later, but there's no doubt about it. The hospital suddenly had these queues of people who had breathing problems, who had to be put on oxygen, who literally couldn't actually survive breathing the air in.

PALMER: So you talked about uncombusted carbon. This was basically because there was a lot of industry it in London and, of course, everybody had a coal fire. That was how we heated, and that was how we cooked our food.

CORTON: Yes, and people did like their coal fire, and one of the problems with trying to introduce legislation to combat this problem, and, believe me, they did try many, many times from the early 19th century onwards. People kept saying, well, we have no real alternative to our coal fire, and even when they did, they were in love with their coal fire. They liked it being the central, the focal part of their living room.

PALMER: You write about how it inspired so many writers and indeed, artists, particularly artists, and how it appears in both our literature and in our painting in this very romantic light as this very sort of mysterious covering, as this, indeed, this personage in our literature.

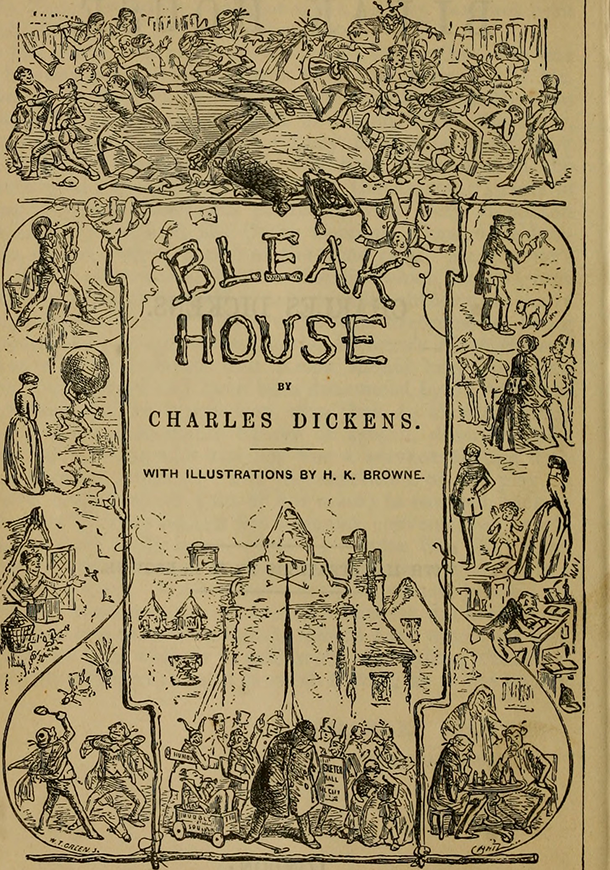

CORTON: Yes, it's interesting that almost all writers at one time or another uses London Fog as a metaphor. Dickens is the one we would first of all go to, and he uses London Fog in a variety of ways. In "Bleak House", he uses it as a metaphor for the law. "Our Mutual Friend" it becomes a metaphor for the corruption of the city. Other writers such as Joseph Conrad use it. The artists, that's an interesting story on its own because English artists, such as George Vicat Cole, W.L. Wyllie, they all tried to paint the London atmosphere as it appeared to them, so with a kind of dirty black haze, showing steam powered engines in the distance creating the smog, but in fact, none of these paintings were really acceptable, because most of the industrialists who were buying paintings at that time, they didn't want to see the products of their own industries being kind of portrayed in paint. So, poor old Wyllie, in fact, he painted a wonderful picture in the 1870s, and somebody actually put a knife through it, he disliked it so much. So it's not really until impressionism takes hold. Monet comes over and paints London fog and he paints in this very impressionistic way. You can see the different colors that the fog produces to his eye. He's got purples, he's got green, he's got yellows. You can see that there's an energy behind it which comes across, but interestingly he never actually exhibited these paintings in London. Most of them were sold by foreign buyers, so even in early 20th century, this kind art wasn't really acceptable.

The London fog is a metaphor for the law in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. (Photo: Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons)

PALMER: You also talk about how deadly the fog was for animals. At the great Smithfield show, this very famous show in London - Smithfield's the meat market - and where they bought all their prize animals, their prize bulls, and the best of the British agricultural product there and the fogs were absolutely deadly for the cattle.

CORTON: Yes, the main one is the 1873 show which there was a weeklong fog outbreak just as the show was opened, and these very well bred, very expensive cattle really suffered. They are seen where they're panting piteously, many of them just die on the spot, they just collapse. In order to try and relieve their pain, they're actually taken outside. But of course, outside is foggy as well, I mean, and the fog was creeping into the Islington insides as well. So about 80 prize cattle died.

PALMER: It's strange. I mean, we're such animal lovers you would've thought that would've galvanized them into action, at least.

CORTON: Well, there were various newspaper reports of how animals in London zoo suffered because of the London fog. Any animal with white fur, such as polar bears, their fur would be covered in these black particles. A, that wasn't very good for them but, B, they of course they would actually try to clean their fur, and buy doing that they would then be taking in even more particles. And in fact, zookeepers said that during foggy days, the animals showed a loss of vitality, they seemed generally depressed, and of course it was argued, well, if this is what's happening to animals in the zoo, can you imagine what is doing to people?

PALMER: Christine, you write about how basically people were constantly getting lost. They couldn't their find way around. Cabbies were getting lost, and even policemen couldn't always find their way around. How did people navigate from A to B if they had to go out in London?

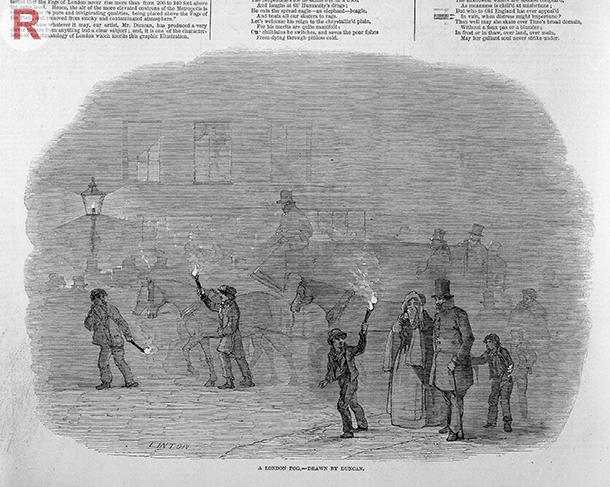

Linklighters lead the way with torches through a London fog, illustrated here in an edition of The Illustrated London News from January 1847. (Photo: Wellcome Images, CC BY)

CORTON: Well, in the 19th century, they used young men, sometimes older men, who would carry links, they were known as linklighters. And they would carry these flaming torches, and promise to lead people back to their homes or to the theatre or whereever. In fact, of course, many of these linklighters were connected to criminal gangs and would often lead the poor unfortunate people up an alley where they would be sandbagged, i.e. hit on the back of a head with a bag of sand, and they would be robbed. But linklighters actually appear in a lot of paintings of foggy days, and you can see them almost causing more trouble than they're worth because they're waving their link torches around, somehow they're burning people's, singeing people's hair. They often kind of drop their torches onto people's feet. So, they're seen as kind of mischief-makers as well as, I say, being tied to crime.

PALMER: It's extraordinary. Giving all these sort of bad things about the fog, why did it really take so long to get it cleaned up?

CORTON: Well, campaigners tried from very early on to clean it up. From the early 19th century, there are people such as a politician called Taylor, Mackinnon in the 1840s. Palmerston had to go in the 1850s. They all tried to bring in smoke abatement acts, but technology isn't there to support these acts, but also it's vested interests. If you're an industrialist and you're trying to make a profit, if you try to improve your chimneys, if you try to clean up the amount of smoke that's going out from the chimney, it's going to cost you money. It means you have to put in new equipment. It means you have to train your stokers to combust the fire quicker, so this is going to cost you money. So of course you're going to be reluctant to an act passed, especially when you yourself as a wealthy industrialist can actually go out and live in the country. You don't have to breathe London's air.

PALMER: And, then, of course, we had interruptions like wars and slumps and the like, and so there were always reasons why this got interrupted.

CORTON: We had the First World War, but after that, of course, then the country was trying to get back on its feet, and, of course, the last thing it wanted to think about was to spend more money on converting people's grates. Then, of course, we have the Second World War. Again in the late 1940s, there's a real effort to produce a really strong Clean Air Act. But the coal industry has been nationalized, and there's a deep suspicion that for the domestic market, the Coal Board is actually supplying a lot of very cheap, dirty coal which is actually producing more smoke, and we're actually sending our more expensive coal abroad because we need the money. So, again, governments are very reluctant to interfere with that. It was really the 1952 smoke that made all the difference.

London’s air is much cleaner than it used to be, but fog and car exhaust still settle into the city now and then. (Photo: Martin Robson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALMER: Well, I'm particularly interested in this because I grew up in Worcestershire, and my local MP, Gerald Nabarro, MP for Kidderminster - I grew up three miles from Kidderminster - was the man who in the end that actually got the Clean Air Act on the books.

CORTON: Yes, it is amazing isn't it? I mean, for your listeners who don't really know anything about Gerald Nabarro, he was actually quite a character. He was against joining the European Union. He was a racist. He was actually caught going around the roundabout the wrong way by a policeman who took a photograph, and he said well it wasn't me who went round the roundabout, it was my secretary and the policeman said well she must have a very fine moustache just like yours, because he had this very distinguished handlebar moustache. So, he's not immediately someone that you would actually say was a hero, but in terms of clean air, he was a hero. He decided that he would push the Clean Air Act through, so he took advice from the smoke abatement societies that were around at the time. He actually introduced a ten-point plan. He had a franking machine for his post that said support the clean air act, so he really put a lot of effort behind it.

The only thing was, the government fell, but both Labour and Conservative parties had clean air measures in their manifestos because I think they saw the tide had turned. People were no longer going to accept a London that actually was covered in smoke. That for as many as three weeks out of every year over a period of winter, you would have to walk in pitch black darkness during the day. I think also, post Second World War, people wanted a cleaner, better way of living. They felt they fought a war, and they wanted actually to see positive measures coming from it, and they weren’t prepared to accept what they saw as a very primitive way of living through winter.

PALMER: The fact that it took the fog so long to get cleaned up and the fact that the fog was ultimately, mostly cleaned up due to, well, the insistence of a few people and the changes in technology, do you think this has a lesson for us in terms of addressing global warming now?

Dr. Christine L Corton is a Senior Member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, and a freelance writer. She worked for many years at publishing houses in London. (Photo: William Knight)

CORTON: Yes, I think one of the lessons is to be patient, but also I think you've got to be persistent, not accept government inaction. I think governments can sit on their hands and just hope it will go away, and I think that's the story of London Fog. Governments were very reluctant to pass acts, even the 1956 Clean Air Act. That really happened because of the Nabarro's insistence and forcefulness and the fact that all the newspapers started saying, “This is a killer. This is poison. We have to do something about it.” Macmillan, who was Minister of Housing for the time, was very reluctant to pass the clean air act. And just as we see our ministers today, and I can only talk, obviously, of the London, England, Great Britain situation, they're very reluctant to interfere with the rights of the driver because we all like to use our cars, and yet we don't want to breathe in the pollution that the exhaust fumes produce. So it's a very similar story to coal fires.

CURWOOD: That’s Christine Corton, the author of “London Fog: The Biography.” She spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Links

Read Christine L Corton’s Guardian article: “Beyond the pall … how London fog seeped into fiction”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth