Canals in Boston?

Air Date: Week of August 7, 2015

“The Back Bay holds some of Boston’s most valuable real estate. Without changes to current infrastructure the neighborhood is vulnerable to flooding from both Fort Point Channel and the Charles River Dam.” –The Urban Implications of Living with Water report (Photo: Urban Land Institute)

Boston is one of the most vulnerable cities in the world to sea level rise. Now urban planners are looking at ways the city can adapt its infrastructure to accommodate storm surges and rising tides. Dennis Carlberg of the Urban Land Institute speaks with host Steve Curwood about his ambitious plan to save Boston's historic Back Bay neighborhood from the rising waters.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Well, Living on Earth is based in Boston – and with its historic harbor – think tea! – and the curves of the wide Charles River, it’s a tourist destination and an attractive place to live and work. But Boston is also among the most vulnerable cities in the world to sea level rise, so now urban planners in Beantown are looking at ways it can adapt its infrastructure to accommodate rising tides. Dennis Carlberg co-chairs the Sustainability Council at the Urban Land Institute, and we walked along Commonwealth Avenue and talked about an ambitious plan to save Boston's historic Back Bay neighborhood from the sea.

CARLBERG: We’re in, I think, the most beautiful part of the city, especially on a nice sunny day like today. This is Boston’s Back Bay; we’re on Commonwealth Avenue which is a broad boulevard that runs east and west and it’s absolutley a gorgeous place.

CURWOOD: It’s a beautiful part of the city but in 1840 it wasn’t here - right?

The John Hancock Tower and the Prudential Center stand amongst Victorian brownstones in Boston’s upscale Back Bay neighborhood. (Photo: Thomas Hawk; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CARLBERG: Correct. We would be standing in marshland, tidal marsh, where it was mucky and muddy. Over the years we’ve filled in much of Boston - about 30 percent of it is on fill, which by its nature is low-lying, and if we have sea level rise, this area we’re standing in would be flooded.

CURWOOD: So how vulnerable is the city of Boston in particular to sea level rise?

CARLBERG: Boston is quite at risk. It’s considered the 8th most at risk in the world and the World Bank suggests that Boston is the 4th at risk when you look at the property values because so much of it is low-lying, as I mentioned 30 pecent of it is on fill. Soon after the end of the century, at the upper end of the projections, 30 percent of the city could be flooded or in the mid-century with a strong surge, plus sea level rise, we could see 6 to 7 feet of water in our city which would be flooding 30 percent of our city.

CURWOOD: Now what happened in Boston when Hurricane Sandy came through?

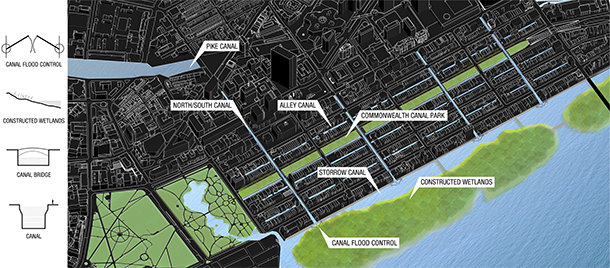

In light of climate change and sea level rise, urban planners at the Urban Land Institute want to incorporate waterways into the infrastructure: alternating north/south streets and east/west alleys would become canals like those in Venice and Amsterdam. (Photo: Urban Land Institute)

CARLBERG: During Hurricane Sandy we had a near miss. Had Hurricane Sandy hit at our high tide, it actually hit just about at our low tide, we would have probably 6 to 7 percent of the city flooded from the storm surge. We’ve had 4 near misses since Sandy which could have had significant flooding in the city. We’ve been very fortunate so far and I think we can learn from New York and if we can make infrastructure improvements before the next Sandy hits, that would be a really good scenario.

CURWOOD: So you and your colleagues at the Urban Land Institute, I understand, were tasked with finding a solution to the prospect of this lovely neighborhood, the Back Bay neighborhood in Boston going under water. So what did you come up with?

CARLBERG: Well we took the tack of – well, let’s welcome it in, what does it look like to live with water in an urban environment? So our group came up with a number of ideas and the one that really floated to the top – sorry the pun – was bringing canals into the Back Bay and what that would that look like.

This image is a representative view of the quandrangle and shows Fawcett Street as it exists today. The projected flood elevation illustrates the potential impact of climate change on the current street realm and building vulnerability. (Photo: Activitas, Hanaa Rohan, City of Cambridge; Courtesy of Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: Canals in the Back Bay of Boston? You want to turn this into – what Amsterdam? Venice?

CARLBERG: Those are very good references and actually that was part of the conversation. Those are very good cities, they’re integrated with water and what would it look to integrate the Back Bay with water.

CURWOOD: How does this work? We think a lot about sea-walls to repel rising tides. Wouldn’t canals just bring more water into the city?

CARLBERG: Well, the water has to go somewhere, so bringing the water into the city in a planned way as opposed to an unplanned way is the strategy we were looking at, and there are sort of two things we need to be conerned about. One is the nearer term, the storm surge and the sea level rise, and one is the longer term, the twice daily high tide. A hundred and twenty years from now, 110 years from now, or a hundred years depending upon how much carbon we put in the atmosphere, we’re going to have a twice daily high tide in the Back Bay. And the other part of that issue is we have a ten foot tide swing, roughly, in Boston, so what do those canals look like at low tide.

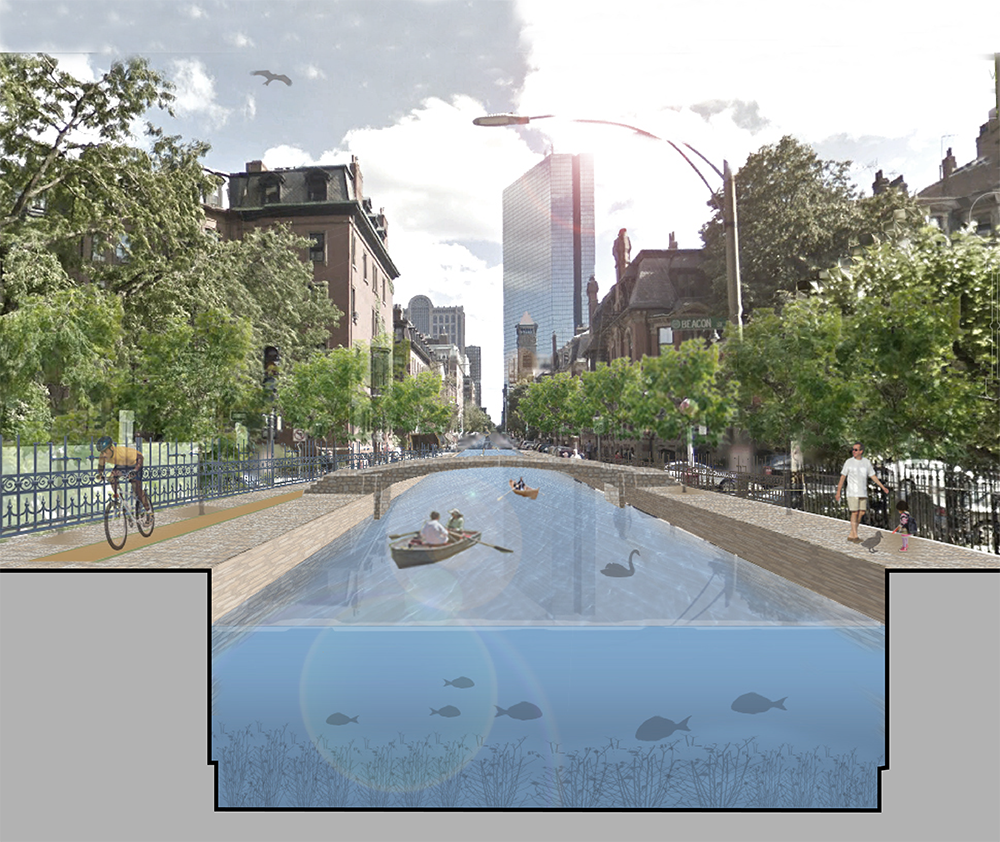

The Back Bay Canal/Street System. The Clarendon Canal shows a typical north/south canal alternating with streets. (Photo: Arlen/Stawasz; Courtesy of the Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: How do you deal with that kind of differential in a tide? If you’ve got ten feet more or less water, either you have very very deep canals or - what do you do?

CARLBERG: Well, I think you have tide gates. So you let the water in and then you let the water out, so it can circulate but you control it, so that the water level is more stable. It fluctuates some but it doesn’t do the whole 10 foot fluctuation.

CURWOOD: So here we are on Comm. Ave, these homes, well they’re at street level, in fact they have basements. If there’s canals here, what keeps the basements from getting all wet?

CARLERG: Well the big issue is you’re going to have a lot of water here, and the basements are going to get flooded, and that value is going to disappear, you’re going to lose that space. One concern we had was if each property is doing its own defenses against sea level rise, we’re going to have a city of walls which is going to kill the value of the city. What makes the city vibrant today is our ability to move in and out of buildings and along our streets, and if we lose that because we have all these walls what is that going to do? So to get to the question of what happens to that lower level, this is a historic district but I think we have to think outside the box a little bit and maybe there’s a zoning that allows for an additional floor or something to take the displaced space. We looked at raising the grade – you’d raise the grade between 4 and 8 feet, to get up higher - maybe not all the way up to first floor because these stoops are really quite beautiful and then you’d build in the canals to let the water in.

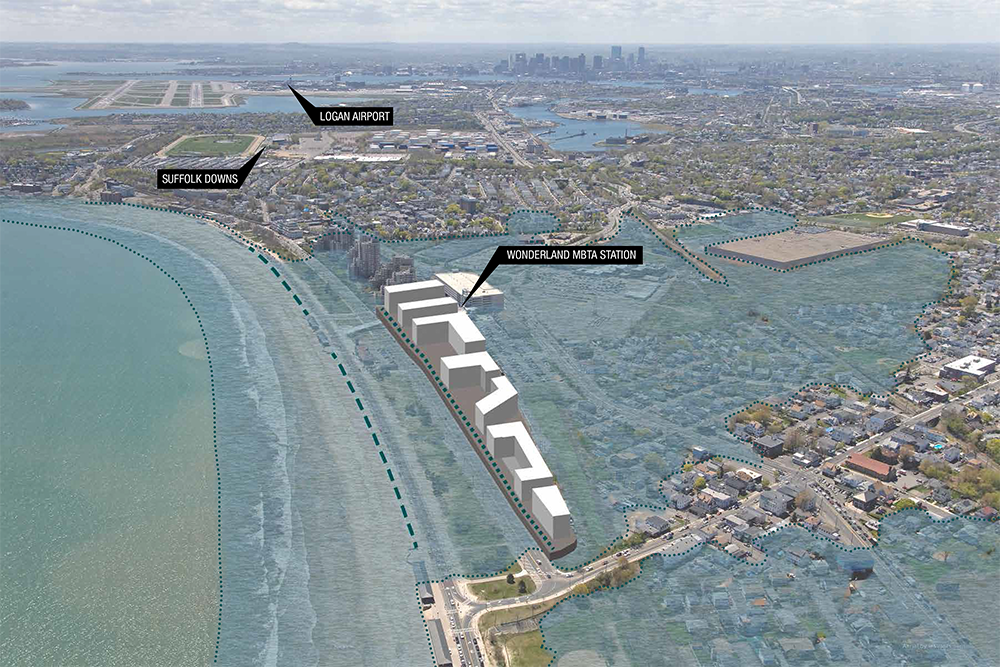

The flood zone based on a FEMA Flood Map for Revere Beach Boulevard (Photo: Arrowstreet; Courtesy of the Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: This is right in the heart of the, well most exclusive part of Boston. I’m thinking, are there actually going to be gondolas and stuff that people can use?

CARLBERG: [LAUGHS] That’s actually what people are talking about. And you know, kayaks and I can’t really quite imagine Venice but certainly we’re talking about boat transportation as well as bicycle and foot traffic too.

CURWOOD: And then you’re telling me when winter comes you’ll be able to skate.

CAARLBERG: That would be great! I'd love to see some skaters on our canals. The challenge is will it be cold enough to have ice on canals – that’s the real question.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I hear all kinds of expensive construction infrastructure projects required to achieve this. Who’s going to pay for it?

CARLBERG: That is a great question. The Urban Land Institute is now embarking on

an exercise to figure out how mechanisms can be developed to finance this stuff, because this is coming whether we like it or not.

CURWOOD: What sense of the economic loss would we be looking at in the city of Boston if nothing were done to halt the advance of the rising waters?

Commonwealth Avenue in Boston would be the site of one of the canals in the Back Bay (photo: Richard Ricciardi; Flickr CC 2.0)

CARLBERG: Well, that is a critical question. What is the cost of doing nothing and that against ths cost of doing something is really kind of the core of our next effort with the Urban Land Institute. If you look at FEMA, they have a 4 to 1 ratio of investment; before it costs one fourth of the investment after an event. That’s only one metric and I think we really need to dig deep to understand what really is at stake here, as well as what the opportunities are. And I think a fundamental thing the Urban Land Institute was looking at when we we were doing this study was how do we preserve the financial value and the human value in our communities in the face of climate change and sea level rise.

CURWOOD: So what are the odds of this happening? How much are people embracing this and how much are people kind of laughing behind their hands?

CARLBERG: [LAUGHS] I think what this has done is this has raised awareness and added another option to look at the broad spectrum of strategies to deal with this problem. The city of Boston, I think, understands the concept but whether this really would happen… I think there’s an incredible amount of investment that would have to happen in a broad way. A fundamental challenge we have here is we have jurisdictional boundaries and we have property line boundaries, and those are all very important boundaries that work very well and have worked very well over time as we’ve developed, but in the face of sea level rise, particularly water knows no boundaries.

Director of Sustainability at Boston University, Dennis Carlberg draws on a map of Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. (Photo: Steve Lipofsky)

CURWOOD: The city of Boston’s almost 400 years old. Science says the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere at the end of the day is likely to give us almost 20 meters – that about 60 feet - of sea level rise. How do we wrap our heads around what’s coming in terms of sea level rise?

CARLBERG: I think the question is really about our carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. That's the core issue. I think all the ideas we’re talking about here are going to look rather quaint if we don't start reducing our carbon footprint substantially, starting right now. That’s what we have to do, that’s the fundamental challenge here.

CURWOOD: Dennis Carlberg directs sustainability for Boston University and is co-chair of the sea level rise subcommittee of the Urban Land Institute in Boston. Thanks for coming by Dennis!

CARLBERG: It’s been great; thank you very much for talking about this important issue.

Links

The Urban Implications of Living with Water Report prepared by the Urban Land Institute

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth