Harsher Winters Related to Arctic Sea Ice Loss

Air Date: Week of October 31, 2014

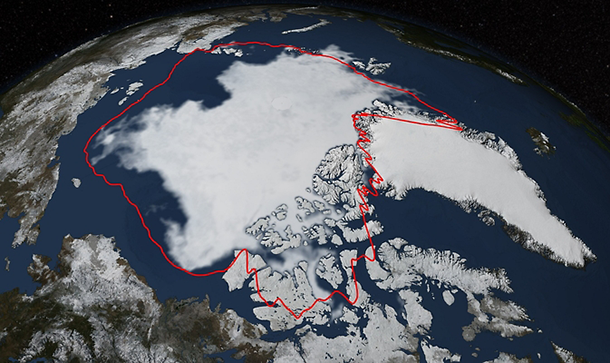

Arctic sea ice hit its annual minimum on Sept. 17, 2014. The red line in this image shows the 1981-2010 average minimum extent. Arctic Sea-ice hits its sixth lowest on record in 2014. Data provided by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency GCOM-W1 satellite. (Photo: NASA/Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio)

A new study published in Nature Geoscience found that the likelihood of unusually cold winters in parts of Eurasia doubles as the Arctic warms and sea ice declines. Host Steve Curwood discusses the findings with Rutgers University climate researcher Jennifer Francis, who also explains how rising temperatures in the far north are changing world weather.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. 2014 is on track to be the warmest year on record, but if you think the trend might bring a mild winter, you could be out of luck. A new study from Tokyo indicates that the increased melting of Arctic sea ice is linked to colder winters, at least in parts of Europe, Asia, and North America. Jennifer Francis is a Research Professor at Rutgers University, who was the first to suggest this link between Arctic ice loss and colder winters. So we got her on the line to explain how it all works. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor Francis.

FRANCIS: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: We're scratching our heads. The study that was just published says cold winters in Europe and Asia are twice as likely to occur given the decline of sea ice in a particular Arctic area. How could this warming way up north create all this cold in the middle of winter?

FRANCIS: [LAUGHS] You know, the atmosphere's a very complicated thing, and we're really just starting to unravel all of the nuances of how it's changing, how the changes in the atmosphere are related to other changes that we’re seeing the climate system, and one of the most obvious of those is the loss of sea ice in the Arctic. In fact there's only about half as much sea ice coverage in the Arctic now as there was only 30 years ago. It's just been disappearing at an amazing rate. One of those regions where the ice is disappearing the fastest is just north of Scandinavia and western Russia, an area called the Barents-Kara Sea area. What we're learning about this area is that it's very important for the atmosphere.

Scientists have been monitoring ongoing changes in Arctic sea ice for decades. By collecting samples of ice as well as a wide range of satellite-based data to document the changes, scientists find that Arctic sea ice is melting at an increasing rate, with half of disappearing in just thirty years. If the trend continues, Arctic sea ice may be gone by the year 2100. (Photo: courtesy of NOAA Photo Library)

When we lose that ice there, the dark ocean underneath during the summertime absorbs a lot of extra energy from the sun, and so that water warms up a lot more than it used to. When fall comes along and the cold air starts to move in again, all that energy that was absorbed through the summer in that region then gets re-emitted back to the atmosphere and that causes the air above this region to warm up a lot. This has the effect of actually bulging the jetstream northward. The jetstream is this fast-moving river of air high over our heads that generates the weather that we experience down here on the surface, and when it is forced to bulge northward like that it compensates by bulging southward just downstream, which would be to the east. When that happens, it allows the cold air from the Arctic to plunge farther south, and so what we're seeing is; during summers when there's less ice than normal in this Barents-Kara Sea area we're finding the jet stream taking this wavier path with the bulge up north of Scandinavia and then a big dip south over Asia allowing that cold air to plunge southward and creating those colder winters.

Arctic sea ice extent on March 14, 1983 (pictured left). Arctic sea ice reached its annual maximum for 2014 on March 21 (pictured right). According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Arctic sea ice extent reached 14.91 million square kilometers (5.76 million square miles) on March 21. Extent is defined as the total area in which the sea ice concentration is at least 15 percent. (Photo: NASA)

CURWOOD: Now some people would say, "Look, way before all the Arctic ice started to melt, some winters were very cold and others were mild”. What about natural variability in weather conditions?

FRANCIS: Yes, natural variability is alive and well. The atmosphere is a very chaotic system and that presents challenges for measuring things like how the atmosphere is going to respond to losses of sea ice and that sort of thing so this recent paper that's triggered this discussion went about this using computer models to simulate the response of the atmosphere to the loss of sea ice. And they did this by running a very sophisticated computer climate model 100 times with the same sea ice loss, and because of natural variability every one of those computer runs looks a little bit different from each other. By doing it 100 times, which is something of course we can't do with the real world, they were able to generate statistics that showed that these cold...extra cold winters in Asia were twice as likely to occur when they put reduced sea ice in this Barents- Kara Sea area as compared to when there was lots of ice in that area. So this is one of the tools we can use to try to get a better handle on how different changes in the climate system are going to affect things like weather patterns.

Bright white ice reflects sunlight from the Earth’s surface. In contrast, open water is dark, and absorbs sunlight. As sea ice melts, more water is exposed, which traps more heat. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

CURWOOD: So, this past winter we heard a lot about the polar vortex...a synonym for a wavy jetstream?

FRANCIS: It is actually, and what we saw this winter was truly not the polar vortex. The real polar vortex actually refers to the general circulation of air around the poles, so there's a polar vortex in the Arctic and there's another one around the South Pole. What happened this past winter that kind of got misnamed the polar vortex, really was that we had one of these big southward dips in the jetstream in combination with the big northward swing over California and the Eastern Pacific. Because we had this big southward dip in the jet stream, a very wavy pattern, it allowed the Arctic air to plunge southward over much of the eastern half of the country. And because the waves were so big in the jet stream that made that pattern very persistent so it hung around for a long time.

As sea-ice melts, polar bears lose some of their habitat. (Photo: Scheherazade Al Arab; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

Yeah it was called the polar vortex and it kind of caught on because vortexes sound dangerous, and sounds like you're going to get sucked down a hole or something like that. Ultimately, even though it wasn't really named properly I think it actually did a lot of good because it got the public interested. It got them listening, and we were able to - what I like to call slide a little spinach into the cheeseburger - where you kind of sneak in a little science while they're talking about all this nasty extreme weather that's going on. So we were able to educate the public a little bit about the jetstream, about what the polar vortex really is and why we think these kinds of patterns should be happening more often in the future as it's related to general global warming - which you know kind of seems like an oxymoron to have global warming lead to these very cold patterns, but this is something that we are able to talk about.

CURWOOD: So in your view, Professor Francis, which came first...the Arctic melting causing the atmospheric shifts or the atmospheric shifts changing the sea ice?

Jennifer Francis is a Researcher Professor at Rutgers’s Institute of Marine & Coastal Sciences

FRANCIS: Well, I have to say yes. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

FRANCIS: So what we know is happening is that the ice is disappearing. The cause of the ice disappearing is a combination of a shift in the atmospheric pattern back in the late 1980s, so we had this shift in the winds in the Arctic that caused a lot of ice to blow out of the Arctic and into the North Atlantic Ocean. This was a natural shift, we've seen shifts like this before, but it just happened to be an unusually strong one that lasted several years, so we lost a lot of extra ice from the Arctic.

Over the last few decades, however, that ice has been thinning and it's been thinning because of increasing greenhouse gases, so that when it does melt back in the summer as it normally does, a lot more of that sun's energy gets absorbed into the Arctic Ocean, which then contributes to even more melting, so we've gotten into this vicious cycle that means that the more ice we lose the more ice we melt and the warmer it gets in the Arctic, and so we're in the situation now where it really can't recover.

CURWOOD: What does that mean?

FRANCIS: Well it means that we are in for a lot more evidence of climate change. We're already seeing an increase in heat waves. We're seeing an increase in the occurrence of heavy downpours and heavy precipitation events. These are completely expected as a result of the effects of global warming because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor and more moisture, and so when it does rain, it rains harder. We're seeing an increase in drought in certain areas, so we are changing the climate system in fundamental ways. People just need to start realizing that and realizing that we're not going to turn this thing around unless we can really come to grips with figuring out ways to put less greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Francis is a Research Professor at Rutgers University's Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences. Thanks for explaining things to us today.

FRANCIS: It was my pleasure.

Links

Read the study on how Arctic sea-ice influences Eurasian winter weather

Jennifer Francis is a Researcher Professor at Rutgers’s Institute of Marine & Coastal Sciences.

Read and watch videos about Arctic Sea-ice melt on NASA’s website

Danish artist melts 100 tons of ice as a stark reminder of climate change

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth