Saving Ourselves- The Green Boat

Air Date: Week of July 12, 2013

A Nebraska woman makes her thoughts known (photo: Kate Schneider/Bold Nebraska)

With so much news about global climate change, species extinction, and habitat loss, many people these days feel eco-anxiety. Psychologist and best-selling author Mary Pipher's latest book is called The Green Boat: Reviving Ourselves in our Capsized Culture. She explains to host Steve Curwood how we can save the earth and restore our mental health at the same time.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Often as not, the news we report could hardly be classified as good news, and with so many stories about global climate disruption, species extinction, and habitat loss, it’s no wonder that many people may be feeling eco-anxiety these days. Well, Mary Pipher has an answer.

She is a psychologist and best-selling author of Reviving Ophelia, a groundbreaking book about adolescent girls, and her newest book is called The Green Boat: Reviving Ourselves in our Capsized Culture. It’s all about how we can have hope, save the earth and restore our mental health at the same time. She joins me now from a studio in her home state of Nebraska. Welcome to Living on Earth, Mary.

Mary Pipher (Photo: Rodale Press)

PIPHER: Thank you very much, Steve, it's really good to be on your show.

CURWOOD: Now you call the first chapter of your book, “Trauma”, and it’s all about the psychological impact of our current environmental crisis, so first explain, why is this traumatic?

PIPHER: Well, I think all of us could be called members of - let’s call it Generation One. No matter where we live, no matter who we are, we are the first generation in the history of the world to be faced with a planetary crisis which we must deal with rapidly and everywhere, and we all know this even when we claim we don’t know this.

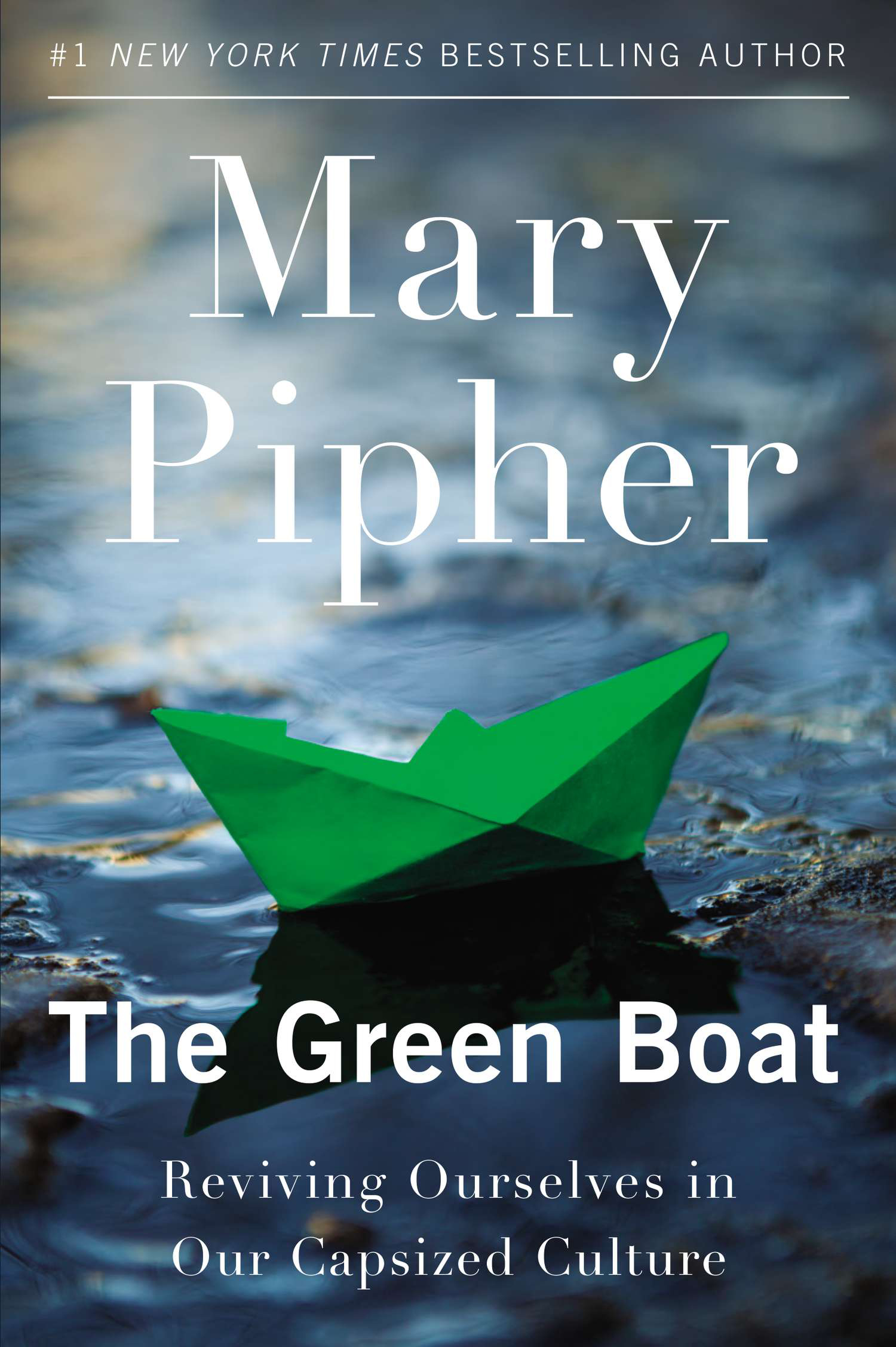

The Green Boat (photo: Rodale Press)

For example, one of the books I found very helpful was a book by a guy named Stanley Cohen, called States of Denial, and he actually looked at what was happening in Nazi Germany during the genocide of the Jews. And what he found was, there was a phenomena that could be called willful ignorance - when something is going on that is too horrible to process, and yet too obvious to totally ignore, and that state of total ignorance, I think, is something that many of us feel - in fact all of us feel. It’s a matter of degree, but all of us go in and out of that state of willful ignorance around global climate change. When we truly think of it, we’re really talking about losing our Mother Earth, our planet, losing everything we love. Personally, that’s overwhelming news.

Nebraskan children demonstrate against the pipeline (photo: Marty Steinhausen/Bold Nebraska)

CURWOOD: In your book, you say, as a society, we’re basically in denial about climate disruption. In fact, we all know that some people don’t believe in it at all. But actually, you’re getting at something deeper than that. Can you explain?

PIPHER: I have in the book, a list of some of the kinds of things we do to block out awareness. We compartmentalize, we have times, all of us, when we want to eat some jumbo shrimp without thinking about the mango groves in Thailand, or we want to read our grandchildren or children a story about polar bears without thinking about the melting ice caps. So we all move in and out of kind of states of denial, and that’s totally understandable. In fact, it’s totally human, and it’s probably adaptive.

I never make the case that there’s something wrong with people for being in denial. I make the case it’s very understandable, and that we all are in denial some of the time, but what I do say is that unless we come out of that denial some of the time and face our situation squarely, we’ll be unable to solve it and deal with it. I have a quote I really like by James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed that is not faced.”

CURWOOD: So what can people do who in fact recognize that there is a problem, but feel paralyzed. What’s the best therapy here?

PIPHER: See, that’s probably the most important question you could ask because people get what I call “distractionable intelligence” which just makes them feel badly, and feel powerless, and I’m really a big fan of “actionable intelligence” that gives people an idea of what to do next. And the main thing I encourage people to do is become engaged with some kind of local work to help the planet. I say action is my antidote to despair.

CURWOOD: So, Mary Pipher, you prescribe action for yourself, and you found yourself helping to mobilize the Nebraska opposition to the Keystone XL Pipeline. How did you get going with this type of activism? Could you describe it for us please?

PIPHER: Well, thank you, Steve. It was a response action to my own despair. I found the best way I could heal myself, in a sense, from feeling miserable, which is not a state I like to be in, was to invite a few friends over and start talking about doing something. And in our state, the biggest, most urgent environmental issue was the Keystone XL Pipeline. So we started out with just two or three people, and we ended up building a statewide coalition of people who have, at least thus far, successfully fought and kept that pipeline out of our state.

CURWOOD: I was struck by your descriptions of the camaraderie you developed between a pretty diverse coalition in your state dealing with the Keystone XL Pipeline. How did that come together?

PIPHER: Well, first of all, one of the big things I believe about groups and action is the most important is it be really good in reinforcing to the members so they’ll keep doing it. So we always had potlucks, and we drank some wine, or we’d meet in parks, and we tried to plan a lot of fun actions because everybody’s real tired and busy, and they wouldn’t want to be involved with things that were just one more meeting in an office and dreary, and we’re always planning ahead and planning events, so we always had things going on that we were looking forward to.

But the biggest surprise for all of us with this group was - I live in Nebraska which is a very conservative state, and our biggest and first allies were conservative ranchers and farmers who really understood the water issues in our state. So we formed a new kind of alliance here in Nebraska between very conservative rural people and people like myself who are urban and progressive, and that was really something, Steve, to see that develop.

CURWOOD: By the way, I noticed you got Nigerians in your coalition in Nebraska, huh?

PIPHER: Yes, I met these Nigerians when I wrote a book called The Middle of Everywhere. And we had a whole lot of events one weekend at a festival, the viral festival, where events happened all over the state, but one of the events was Africans against the pipeline with our African refugee community. And some of the people who participated in that - the Ogoni people - had been people who were run out of Nigeria and many of their leaders killed because they had tried to stop a pipeline from coming down their river and in their area many years ago. And were driven out of Nigeria and ended up as refugees in Lincoln, and they came, and they very ardently spoke about how important it was to stop this pipeline. They said, ‘first we saw the plants die, then we saw the animals die, then we saw the people die.” It was a very dramatic event, and a fun event too, I might add, to have those cowboys and Africans together in the same park.

CURWOOD: You started this process pretty depressed by your own description. How are you doing now?

PIPHER: Well, bless your heart for asking. I’m about as happy as anybody else, is how I’d put it. Happy some days, not so much the other. But I’ll tell you, feeling you’re powerless is a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you think you’re powerless, you’re darn well going to be powerless. On the other hand, if you start acting as if you have power and influence, you engage in hopeful process, and you’re likely to find other people like that who will engage in that hopeful process with you. And those people start being close friends, and we’ve had a lot of fun and we’ve really grown to care about each other and, all in all, this experience of both riding the green boat and fighting the Keystone XL has been one of the more transformative experiences of my life, Steve.

CURWOOD: “Transcendence,” that’s what you labeled one of your chapters. Why is this so profound? Why do you think it had such a profound effect on you?

PIPHER: For me, the three transcendent responses are action, getting involved; increasing one’s own moral imagination, becoming kinder and more connected to other people and, in fact, other living beings; and then the third is finding more and more ways to be amazed and “blissed out” by the universe. Because if you’re doing the hard work that our group has done, that anyone does that looks honestly at the world, I think that needs to be balanced by lots of experience in which you’re just having a wonderful time, looking at the stars or sitting by water or enjoying your fresh grown tomatoes with your friends. So I think all three of those are really wonderful ways to move beyond despair and sorrow and into something bigger.

CURWOOD: At one point you write, and let me quote you here, “The necessary conditions for revival are not economic ones, but rather mindfulness and community.” Some might say that mindfulness and community can certainly help, but they might not be enough to solve a problem as serious as the climate crisis. What would you say?

PIPHER: But what is a better solution? You know what I think’s going to happen...first of all, nobody knows if we have solve these problems or not, and I’m not a Pollyanna. I don’t claim to know more than other people who’ve looked into things know, and nobody claims to know that’s being honest and knows what they’re talking about. We really have no idea what time it is in terms of the history of hominids and any other species - we have no idea what time it is. But what I do think, we’ll say this, if anything we’ll say this, it’s people all over the world waking up, realizing the situation they’re in, and realizing that they want to work together to build a sustainable future. And the interesting thing about that, Steve, is that is not some “pie in the sky” fantasy. I mean, that is happening all over the world. I can hardly get on my internet or get on the world wide web without news of some great new group that’s forming, or some new coalition of groups that’s forming somewhere on Earth to protect the planet. So I think it’s very likely that they’re will be a change in consciousness in the next few years when we need that consciousness to change. And that especially when we all know about each other and can connect and inspire each other, I think change can move very rapidly. Change has moved very rapidly in the history of the world as you know.

CURWOOD: Now, not everyone has the ability to get involved with a big political cause like the Keystone XL Pipeline fight as you got involved. So what advice do you have for people about maybe some littler things they can do in their lives.

PIPHER: First of all there’s always a cause nearby. Sadly, there’s enough issues and problems out there probably within ten blocks of your home you can find a good environmental cause to be involved with. One very simple thing I’m involved with now that’s virtually an issue everywhere is working with local power companies to encourage them to use a lot more sustainable and clean energy, but the main thing I tell people about getting involved is do what you love. Do what you have the skills to do and love to do and have a passion for it. Because, there’s so many causes, there’s so many issues, and all of the gifts of all of us will be required to make this work.

So if you have gift for art, if you have a gift for baking pies, if you have a gift for public speaking, or building. Whatever it is you have a gift for, that gift will be useful locally in some cause, and all you need, by the way, to be a group, is one other person. You and one of your friends on a front porch or sitting in your apartment can form a group, and the two of you can find some little action to begin with that’s going to make you feel like you’re a part of something larger than yourself and get you started on a path toward reclaiming power. And the other is make sure you’re savoring your life. Make sure you’re enjoying yourself and doing everything you can to look at the sky, look at the stars, walk beside water when you can, to be with positive people who are actively engaged and trying to have an impact on the world. Whether or not we can change the world, I guarantee you, Steve,that will change us.

CURWOOD: Mary Pipher is a psychologist and author of the new book The Green Boat. Thanks for joining us, Mary.

PIPHER: Thank you, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth