Tornado Storm Kings!

Air Date: Week of March 22, 2013

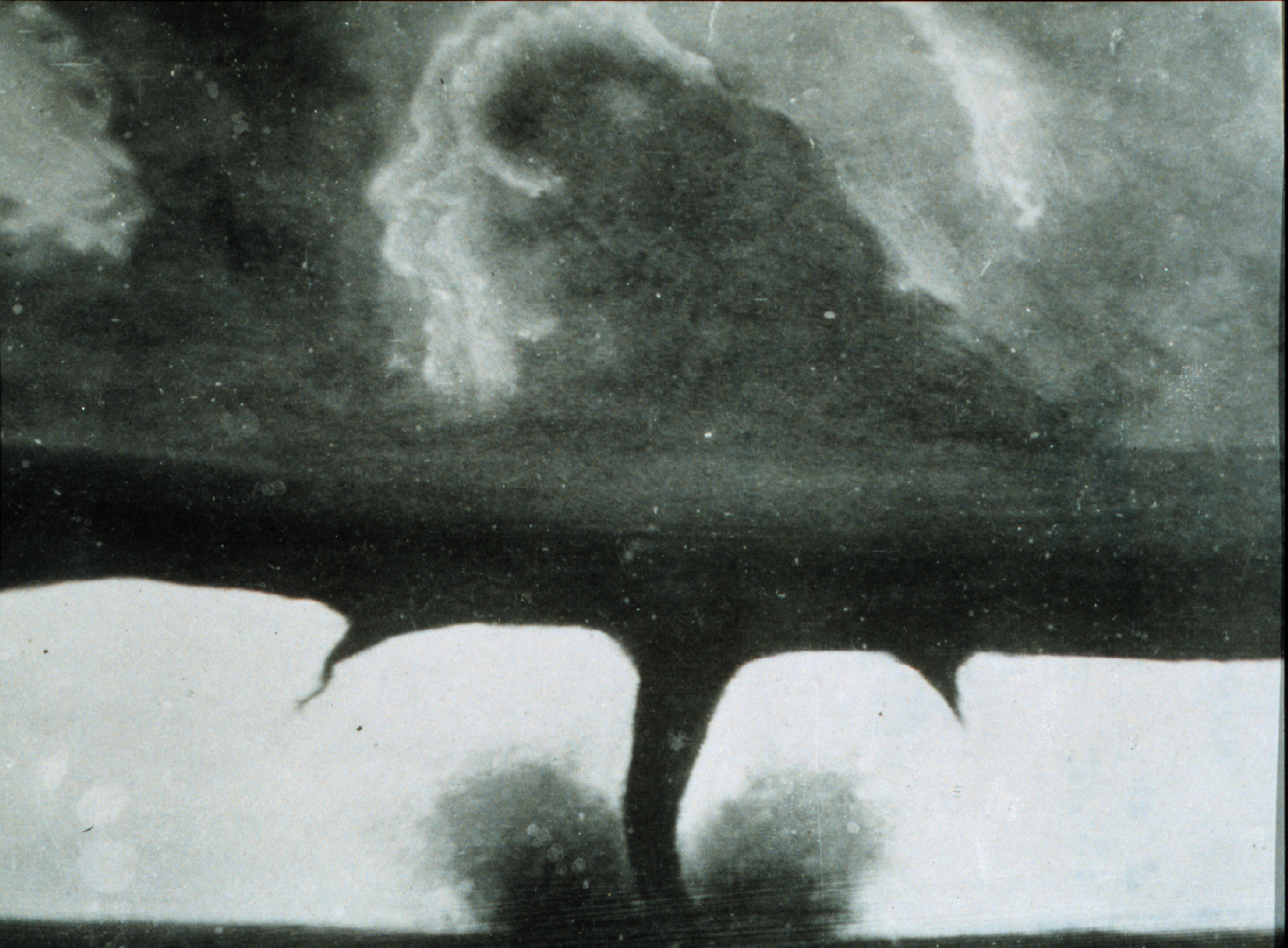

The earliest known tornado photograph, taken in South Dakota in 1884, heavily retouched for sale as a postcard. (Photo: NOAA)

The vast majority of tornadoes touch down on the Great Plains of North America, tornado alley. Like many Midwesterners, Lee Sandlin has been fascinated by tornadoes since childhood. He joins host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book 'Storm Kings: the Untold History of America’s First Storm Chasers.'

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. From The Wizard of Oz to Twister, tornadoes loom large in the American imagination, and throughout our history. Lee Sandlin’s new book “Storm Kings: the Untold History of America’s First Tornado Chasers” outlines the history of tornado science and describes some of the worst tornadoes in U.S. history. Lee Sandlin says his interest in deadly storms began as a child, growing up in tornado alley.

SANDLIN: When you grow up in the midwest, you're always aware of tornadoes in a way that people elsewhere in the country really aren’t. You get tornado preparedness in schools, people tell you stories about tornadoes that they saw when they were children. It's this kind of ongoing fact of life.

Lee Sandlin (photo: Peter Wynn Thompson Photography)

CURWOOD: Tell me about the tornadoes you've witnessed yourself.

SANDLIN: I was in a small tornado when I was 17 years old. I was just at home. It was a summer day. It had been raining all day. And then suddenly it turned sunny and clear and I thought I’d go out for a walk. I was standing at the door of my house literally about to step outside. And I was looking out through the screen door and the street immediately got pitch black. And every single thing that wasn't nailed down was swept up straight into the air.

Now this was a weak tornado, but it was terrifying enough that it's stuck with me. And the other lesson I took from it was that you can be in a tornado and not really realize what's happened because they move so quickly that a lot of the stuff we think of as characteristic, like a funnel cloud - you often don’t see it. I didn’t see it. If I hadn’t know intellectually that it was a tornado I would have had no idea what was happening.

CURWOOD: Now one of the most interesting things that I took away from this book was the realization that, at least for people who came from Europe and Africa, tornadoes are totally unfamiliar. Why are tornadoes such a uniquely American - North American phenomena?

SANDLIN: It's a freak of geography actually. What you need for tornado formation are two different kinds of air masses meeting. One, you need very cold dry air, and for the other you need very moist humid air and hot air, and the American Midwest where you have air coming down from Canada and air coming up from the Gulf of Mexico are the perfect conditions for tornado formation. And the other factor too is there no mountain ranges in the Midwest. There are no details of landscape or crosscurrents of air that will dilute the effect of these two air masses meeting. So you tend to get these extraordinarily strong destructive storms forming there.

CURWOOD: Now, tell me...who was the very first storm chaser?

SANDLIN: Well in the literal sense of chasing the storm, the first person I found out who did it was Benjamin Franklin of all people.

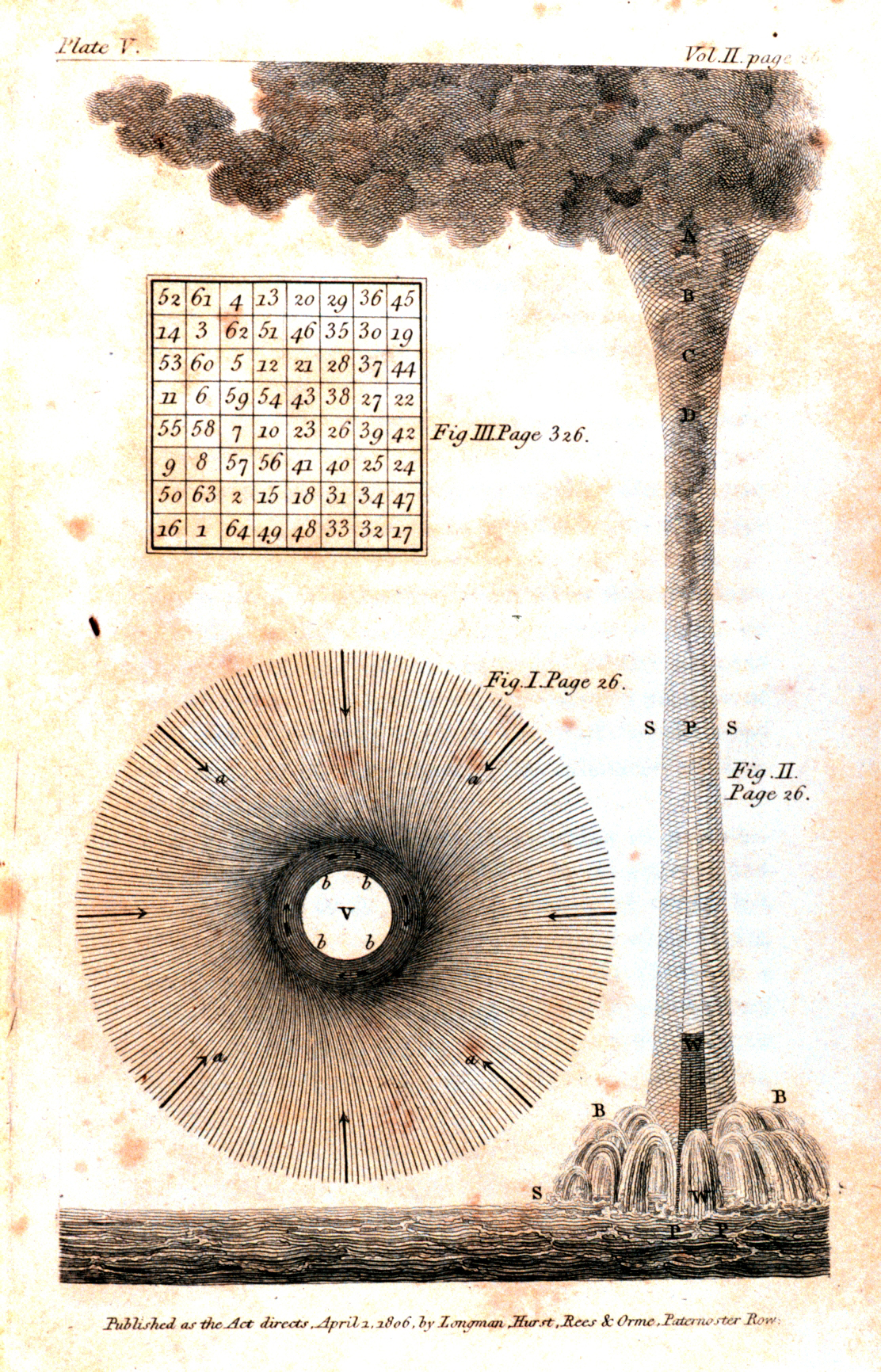

Benjamin Franklin’s conception of a waterspout. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: The guy on the 100 dollar bill?

SANDLIN: You got it. He had a brief period where he was fascinated by tornadoes. And he, just out of a fluke, he happened to see one forming. It was a very small tornado. When he and a bunch of friends were out riding, everyone else was frightened, but he went off riding on horseback chasing this tornado through the forest and so that’s the literal beginning of tornado chasing as a hobby.

CURWOOD: Did he catch up with the storm?

SANDLIN: He said...he claimed that he got so close to it that he was able to lash it with his riding crop. I don't know, he may have been exaggerating just a little bit there. He got pretty close to it, but it was a very weak tornado and it broke up fairly quickly, so nobody was hurt. He was fine. But he was exhilarated by it and that fuels his fascination for quite a while.

CURWOOD: In your book you describe the great storm war that was a debate between meteorologists over the causes of tornadoes

SANDLIN: Yes, in the early 19th century.

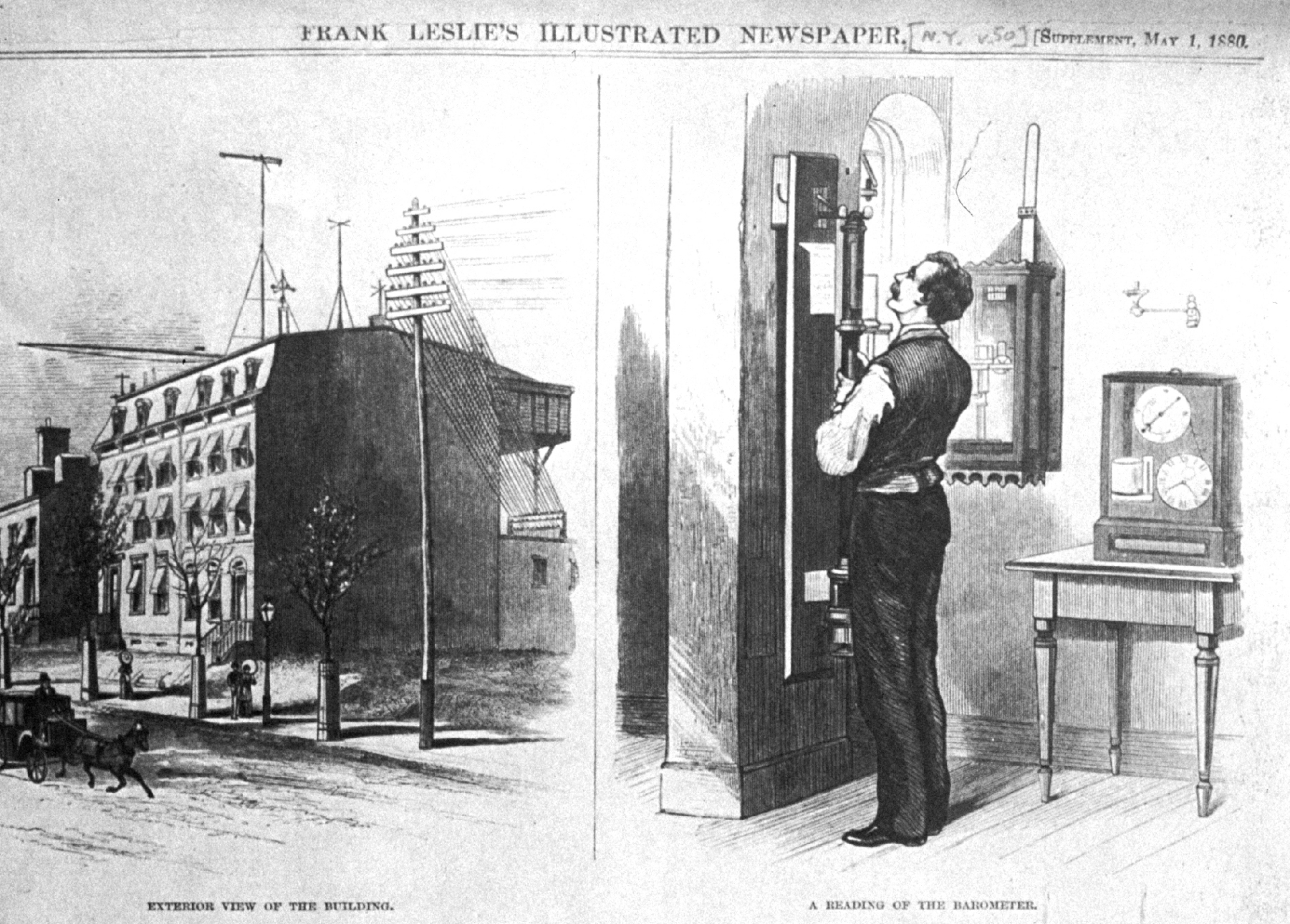

The Signal Corps headquarters in Washington City, 1880. (photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, NOAA)

CURWOOD: Describe that debate for us. Who was involved, and what was the disagreement?

SANDLIN: Well, this is really kind of one of the peculiarities of the history of American science. There were two great experts on storms in the early 19th century. One was a man named Espy and the other was a man named William Redfield. Espy was...he considered himself America’s first professional meteorologist. Redfield was more of an enthusiastic amateur.

Espy was the person who realized the core mechanism of the tornado, which is a phenomenon called convection, a rising column of air in the atmosphere. And this is a major scientific breakthrough - he doesn’t get as much credit for it now as there used to be, but he figured that out.

And Redfield also made a dramatic, dramatic breakthrough. He was the first person to realize that storms like tornadoes and hurricanes rotated, which is something that nobody had believed before.

So you had these two guys - one of them thought a tornado was a rising column of air. And the other thought a tornado was a rotation on the ground. And they detested each other. And they disagreed with each other. And they refused to believe that the other could be right. And so they spent two decades feuding in scientific periodicals over which one was right. And it couldn't be resolved, because the truth is that they were both right, but neither was able to concede that the other might have a point. And this fight really paralyzed meteorology for the first half of the 19th century.

CURWOOD: So, a little science lesson here. Talk to me about convection, and how it’s related to tornadoes.

SANDLIN: Sure, the easiest way to picture this is that if you've ever noticed when you're looking at a pot of boiling water on the stove, when it begins to boil, you’ll see little bubbles coming up from the bottom. The bubbles don't appear randomly. They tend to appear in, like, single file lines rising through the water. So what's happening there is hot water at the bottom is rising through the colder layer of water to the surface.

Now the exact same thing can happen in Earth’s atmosphere. The air near the surface can be very warm, and the air above very cold - which is a very unstable relationship because hot air rises just like hot liquids rise. And the result of that, tornadoes are essentially kind of a safety valve mechanism by which very, very large amounts of hot air at the surface move very, very quickly through cold air into the upper air, and so it’s a way of restoring atmospheric equilibrium.

CURWOOD: It’s funny you call this is a safety valve. I don’t think anyone would think much of...

SANDLIN: Around the surface, no, they’re horrible. But it is true that almost everything in nature tends to look for equilibrium, and that's a way of restoring equilibrium to a violently unstable situation.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about James Espy. He comes across as a particularly interesting figure in your book.

SANDLIN: He was the first celebrity meteorologist.

CURWOOD: You write that he actually thought he could control the weather. I mean, what was his idea?

SANDLIN: Well, he thought storms formed because hot air rose from the surface into cold air aloft and that the moisture in the hot air would shed out and fall as rain. Now that is a fact, exactly correct. But he drove a strange consequence from that because he thought if that's true and he really wanted to get hot air rising in cold air, what would you do? You’d build a fire. And if you built a big enough fire, you could create storms over a very large amount of the country.

He was convinced that if they built fires all through America they could control the weather. He was quite serious about this. He worked out maps as to where all the fires should all be set and they would be burning permanently. He said it would cure and permanently end droughts in America; it would let people control where the rain would fall and where it wouldn’t. And he thought - this would be in one stroke - we could remake the entire American landscape using this method.

And the odd thing about this story is that everybody then just assumed he was nuts. No one took the idea seriously, but he wasn't technically wrong. Very large fires - this is not really well-known - but very, very large intense fires do create thunderstorms. What he didn't realize is that even though he could create storms that way, it would be inherently unstable. It was also just a basic problem that he refused to think through...which is the worst thing you want to do in a drought area is build a really big fire!

CURWOOD: In your book, you write that fire can trigger a tornado. You tell us the story of the Peshtigo fire tornado of 1871.

SANDLIN: Yes. The Peshtigo fire tornado is one of the most catastrophic weather events on record. It was a storm that formed at the heart of an immense forest fire in northern Wisconsin. At the heart of the fire, this column of air seems to have formed into a tornado. And the tornado was so intense that it started drawing the flames of the fire into itself and it moved through the forest as this titanic column of flame.

It came over the town of Peshtigo and destroyed it almost instantly. It tore full steam engines, rail engines, off the tracks and smashed them in midair. It blew up every house, every structure that it came across, and went instantly up in flames. 1,500 people died. Survivors, the only survivors, had plunged themselves into the river and stayed submerged as the tornado passed directly over. It was an absolutely catastrophic event.

CURWOOD: Now as the National Weather Service gets going, tornado prediction becomes extremely controversial. Why?

SANDLIN: Well, there were two reasons. One, I think was a good reason and one was not so good. The good reason was that tornado prediction was a very crude science and people believed that predicting tornadoes could cause panic, that it could be worse than the actual tornadoes. The other reason was that the weather service was being pressured by business interests and real estate people in the Midwest who did not want the idea spread that tornadoes were real problem. So they were pressured to underreport tornadoes, in fact for a long time for several decades the weather service banned forecasters from the word “tornado”.

CURWOOD: We have tornado warnings today. What changed?

SANDLIN: Well what’s changed specifically is that after World War II, the Air Force came up with a method of predicting tornadoes that they were keeping to themselves. It really was very crude technology. All they actually had to work with were reports from weather spotters and from other weather stations and a radar which they had salvaged from a World War II vintage bomber.

They tried to get the National Weather Service interested in it, but they wouldn't do it, and the news got out sort of through underground channels. What would happen is that when they had these tornado forecasts issued, people on the Air Force bases would call their relatives who were civilians and tell them about the warnings, and gradually through Oklahoma and Texas in the early 50s, the word spread that the Air Force had this secret tornado predicting facility, and there were congressional hearings about that, and that led to the National Weather Service lifting their tornado ban.

CURWOOD: Now to this day tornadoes remain, of course, dangerous, and difficult to predict. Think of Joplin, Missouri, 2011, that tornado killed more than 160 people.

SANDLIN: Yes, it did. The thing about that tornado is in some ways the most alarming is that the weather system, prediction system, as it exists now, worked very well. They had a lot of lead time. They had a lot of warning, and people still either didn't believe it or ignored it until the tornado was right on top of them. And also another factor which is a growing problem in the midwest, is that the midwest is getting very heavily built up, and most of the new residential construction has nothing that would serve as a good tornado shelter; no basements, no interior closets, no storm cellars... people are essentially building, pretending that tornadoes don't exist. And so in Joplin, even people who wanted to take shelter often couldn’t find any shelter to take. So it feels in some ways like we’re going backwards with tornado preparedness.

CURWOOD: So what are the myths that still persist about tornadoes?

SANDLIN: Certainly when I was kid, everything they told us in school about tornadoes was wrong. They told us to hide in the southwest corner of the basement. That was a famous one when I was child. They told us to open windows when tornadoes approached because there was a vacuum at the center of the funnel and the air pressure inside the building would push outward and cause your house to explode. Now that idea is completely false and dated back to the 19th century and nobody never examined it.

CURWOOD: And what other myths do we have about tornadoes?

SANDLIN: Oh, that tornadoes don’t go into cities which is false, that they can’t cross rivers, that they won't go up and down hills. These are all ideas that are very dangerous to trust.

CURWOOD: So how much tornado chasing do you do now?

SANDLIN: Well, I don't do any now, and I've only done a little mostly in an amateur level back when I was younger. But it’s becoming this huge, huge industry now. A tornado chaser once told me that the biggest danger from tornado chasing isn't the tornado itself - it's getting rear-ended by another tornado chaser. It’s almost like a spectator sport, and if you look at YouTube there's a whole vast genre of amateur video of tornadoes actually called “torn porn”.

CURWOOD: What effect is climate change having on tornadoes?

SANDLIN: Well that is the big question, and I'm afraid the answer is nobody knows. Tornadoes don't appear to be growing more prevalent. It’s just our detection systems are more prevalent. But you know, climate change means the atmosphere is becoming more unstable, and since tornadoes are the product of instability, it's at least possible that what's going to happen is that we’re going to be seeing more tornado outbreaks, but no one knows that for sure yet. We're just going to have to wait and see.

Storm Kings cover (photo: Random House)

CURWOOD: What lessons do you want people to take away from your book?

SANDLIN: I think that one of the things that I would think would be the best lesson is that we think we have a handle on the weather, and the weather still has a lot of surprises. Things like tornadoes may turn out to be inherently uncontrollable and unpredictable. We have a tendency to believe sooner or later we will get control of all of the phenomena of the Earth, and I don't think that's really ever going to happen.

CURWOOD: Lee Sandlin’s book is called “Storm Kings: the Untold History of America’s First Tornado Chasers.” Thanks so much, Lee.

SANDLIN: This has been a pleasure.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth